SUBSCRIBE TO OUR FREE NEWSLETTER

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

5

#000000

#FFFFFF

To donate by check, phone, or other method, see our More Ways to Give page.

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

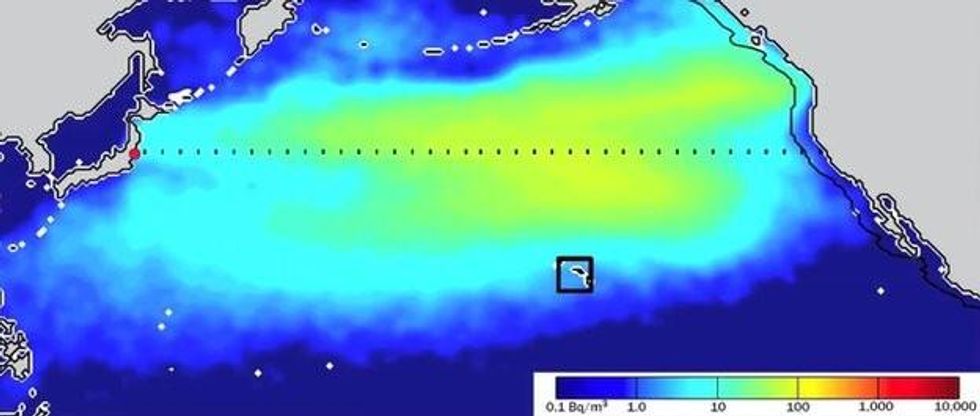

A radioactive plume released from the Fukushima meltdown may have already reached the west coast of North America and is expected to reach the U.S. in April, said a panel of researchers in Honolulu Monday. However, without any federal or international monitoring, scientists are bereft of "actual data," guessing at the amount of radiation coming at us.

Monitors along the Pacific U.S. coast have yet to detect any traces of cesium-134, said Ken Buesseler, a chemical oceanographer at the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution (WHOI), speaking on a panel at the meeting of the American Geophysical Union's Ocean Sciences.

However, sampling undertaken by Dr. John Smith at the Bedford Institute of Oceanography has found traces in the waters outside of Vancouver, B.C.

LiveScience reports:

Smith and his colleagues tracked rising levels of cesium-134 at several ocean monitoring stations west of Vancouver in the North Pacific beginning in 2011. By June 2013, the concentration reached 0.9 Becquerels per cubic meter, Smith said. All of the cesium-134 was concentrated in the upper 325 feet (100 m) of the ocean, he said. They are awaiting results from a February 2014 sampling trip.

Their water samples have helped develop models that forecast the "probable future progression of the plume," said Smith.

According to Buesseler, based on those models, initial traces of radioactive isotopes from Fukushima should be detectable along the Pacific coast of the United States in April.

One of the radioactive isotopes that is formed during a nuclear accident is cesium-134. With a short half-life of two years, any traces of it detected by monitoring instruments can be specifically attributed to the Fukushima nuclear accident.

Another isotope, cesium-137, decays very slowly with a half-life of 30 years. Though traces of cesium-137 have been detected in the world's oceans, their source may be attributed to previous nuclear-weapons tests.

One shortcoming of the current models available to the scientists is that lack of solid data is creating varying predictions about the amount of radiation and when it is expected to reach the U.S.. And though the estimated levels fall far shorter than acceptable drinking water concentrations, according to the WHOI, the concern is not direct exposure but rather the "uptake by the food web and, hence, the potential for human consumption of contaminated fish."

"To my mind, this is not really acceptable," said Buesseler, speaking of the variation between the predictive models. "We need better studies and resources to do a better job, because there are many reactors on coasts and rivers and if we can't predict within a factor of 10 what cesium or some other isotope is downstream--I think that's a pretty poor job."

Individuals have recently spread alarm about the presence of radioactive isotopes already found along the Pacific coast, although those concerns were debunked.

Without any federal or international agencies currently monitoring ocean waters from Fukushima on this side of the Pacific, Buesseler and the WHOI have had to recruit volunteers to collect seawater at 16 sites along the California and Washington coasts and two in Hawaii and ship the samples back to the Cape Cod, Mass. laboratory.

"We need to know the real levels of radiation coming at us," said Bing Dong, a retired accountant and one of the volunteers with the WHOI project. "There's so much disinformation out there, and we really need actual data."

_____________________

Dear Common Dreams reader, The U.S. is on a fast track to authoritarianism like nothing I've ever seen. Meanwhile, corporate news outlets are utterly capitulating to Trump, twisting their coverage to avoid drawing his ire while lining up to stuff cash in his pockets. That's why I believe that Common Dreams is doing the best and most consequential reporting that we've ever done. Our small but mighty team is a progressive reporting powerhouse, covering the news every day that the corporate media never will. Our mission has always been simple: To inform. To inspire. And to ignite change for the common good. Now here's the key piece that I want all our readers to understand: None of this would be possible without your financial support. That's not just some fundraising cliche. It's the absolute and literal truth. We don't accept corporate advertising and never will. We don't have a paywall because we don't think people should be blocked from critical news based on their ability to pay. Everything we do is funded by the donations of readers like you. Will you donate now to help power the nonprofit, independent reporting of Common Dreams? Thank you for being a vital member of our community. Together, we can keep independent journalism alive when it’s needed most. - Craig Brown, Co-founder |

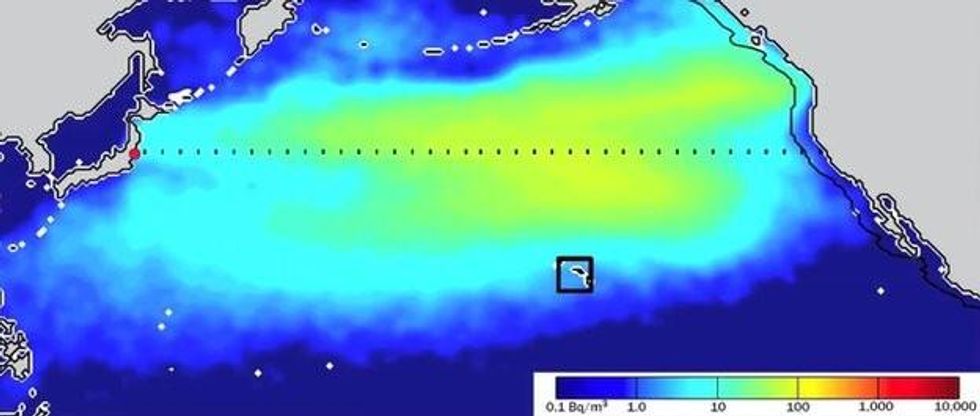

A radioactive plume released from the Fukushima meltdown may have already reached the west coast of North America and is expected to reach the U.S. in April, said a panel of researchers in Honolulu Monday. However, without any federal or international monitoring, scientists are bereft of "actual data," guessing at the amount of radiation coming at us.

Monitors along the Pacific U.S. coast have yet to detect any traces of cesium-134, said Ken Buesseler, a chemical oceanographer at the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution (WHOI), speaking on a panel at the meeting of the American Geophysical Union's Ocean Sciences.

However, sampling undertaken by Dr. John Smith at the Bedford Institute of Oceanography has found traces in the waters outside of Vancouver, B.C.

LiveScience reports:

Smith and his colleagues tracked rising levels of cesium-134 at several ocean monitoring stations west of Vancouver in the North Pacific beginning in 2011. By June 2013, the concentration reached 0.9 Becquerels per cubic meter, Smith said. All of the cesium-134 was concentrated in the upper 325 feet (100 m) of the ocean, he said. They are awaiting results from a February 2014 sampling trip.

Their water samples have helped develop models that forecast the "probable future progression of the plume," said Smith.

According to Buesseler, based on those models, initial traces of radioactive isotopes from Fukushima should be detectable along the Pacific coast of the United States in April.

One of the radioactive isotopes that is formed during a nuclear accident is cesium-134. With a short half-life of two years, any traces of it detected by monitoring instruments can be specifically attributed to the Fukushima nuclear accident.

Another isotope, cesium-137, decays very slowly with a half-life of 30 years. Though traces of cesium-137 have been detected in the world's oceans, their source may be attributed to previous nuclear-weapons tests.

One shortcoming of the current models available to the scientists is that lack of solid data is creating varying predictions about the amount of radiation and when it is expected to reach the U.S.. And though the estimated levels fall far shorter than acceptable drinking water concentrations, according to the WHOI, the concern is not direct exposure but rather the "uptake by the food web and, hence, the potential for human consumption of contaminated fish."

"To my mind, this is not really acceptable," said Buesseler, speaking of the variation between the predictive models. "We need better studies and resources to do a better job, because there are many reactors on coasts and rivers and if we can't predict within a factor of 10 what cesium or some other isotope is downstream--I think that's a pretty poor job."

Individuals have recently spread alarm about the presence of radioactive isotopes already found along the Pacific coast, although those concerns were debunked.

Without any federal or international agencies currently monitoring ocean waters from Fukushima on this side of the Pacific, Buesseler and the WHOI have had to recruit volunteers to collect seawater at 16 sites along the California and Washington coasts and two in Hawaii and ship the samples back to the Cape Cod, Mass. laboratory.

"We need to know the real levels of radiation coming at us," said Bing Dong, a retired accountant and one of the volunteers with the WHOI project. "There's so much disinformation out there, and we really need actual data."

_____________________

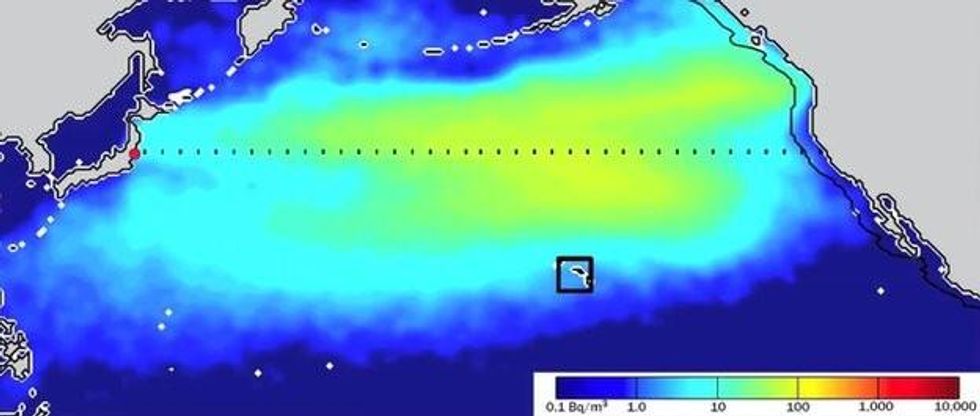

A radioactive plume released from the Fukushima meltdown may have already reached the west coast of North America and is expected to reach the U.S. in April, said a panel of researchers in Honolulu Monday. However, without any federal or international monitoring, scientists are bereft of "actual data," guessing at the amount of radiation coming at us.

Monitors along the Pacific U.S. coast have yet to detect any traces of cesium-134, said Ken Buesseler, a chemical oceanographer at the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution (WHOI), speaking on a panel at the meeting of the American Geophysical Union's Ocean Sciences.

However, sampling undertaken by Dr. John Smith at the Bedford Institute of Oceanography has found traces in the waters outside of Vancouver, B.C.

LiveScience reports:

Smith and his colleagues tracked rising levels of cesium-134 at several ocean monitoring stations west of Vancouver in the North Pacific beginning in 2011. By June 2013, the concentration reached 0.9 Becquerels per cubic meter, Smith said. All of the cesium-134 was concentrated in the upper 325 feet (100 m) of the ocean, he said. They are awaiting results from a February 2014 sampling trip.

Their water samples have helped develop models that forecast the "probable future progression of the plume," said Smith.

According to Buesseler, based on those models, initial traces of radioactive isotopes from Fukushima should be detectable along the Pacific coast of the United States in April.

One of the radioactive isotopes that is formed during a nuclear accident is cesium-134. With a short half-life of two years, any traces of it detected by monitoring instruments can be specifically attributed to the Fukushima nuclear accident.

Another isotope, cesium-137, decays very slowly with a half-life of 30 years. Though traces of cesium-137 have been detected in the world's oceans, their source may be attributed to previous nuclear-weapons tests.

One shortcoming of the current models available to the scientists is that lack of solid data is creating varying predictions about the amount of radiation and when it is expected to reach the U.S.. And though the estimated levels fall far shorter than acceptable drinking water concentrations, according to the WHOI, the concern is not direct exposure but rather the "uptake by the food web and, hence, the potential for human consumption of contaminated fish."

"To my mind, this is not really acceptable," said Buesseler, speaking of the variation between the predictive models. "We need better studies and resources to do a better job, because there are many reactors on coasts and rivers and if we can't predict within a factor of 10 what cesium or some other isotope is downstream--I think that's a pretty poor job."

Individuals have recently spread alarm about the presence of radioactive isotopes already found along the Pacific coast, although those concerns were debunked.

Without any federal or international agencies currently monitoring ocean waters from Fukushima on this side of the Pacific, Buesseler and the WHOI have had to recruit volunteers to collect seawater at 16 sites along the California and Washington coasts and two in Hawaii and ship the samples back to the Cape Cod, Mass. laboratory.

"We need to know the real levels of radiation coming at us," said Bing Dong, a retired accountant and one of the volunteers with the WHOI project. "There's so much disinformation out there, and we really need actual data."

_____________________