SUBSCRIBE TO OUR FREE NEWSLETTER

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

5

#000000

#FFFFFF

To donate by check, phone, or other method, see our More Ways to Give page.

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

We need farms, not fracking.

This was the message from a group of concerned activists on Sunday afternoon as they blocked a Shell fracking site in Pennsylvania in part of the wave of rising actions against fossil fuels.

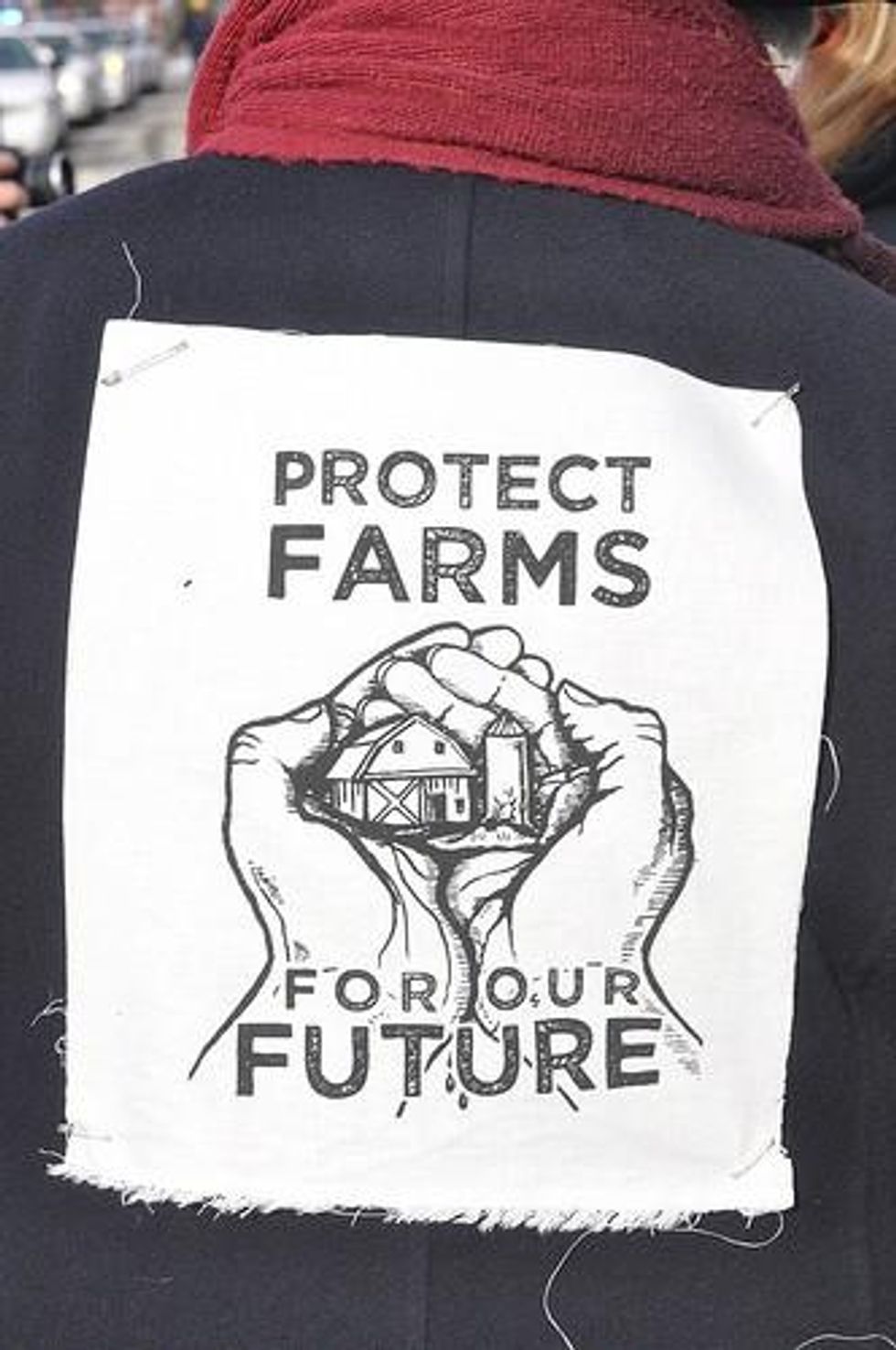

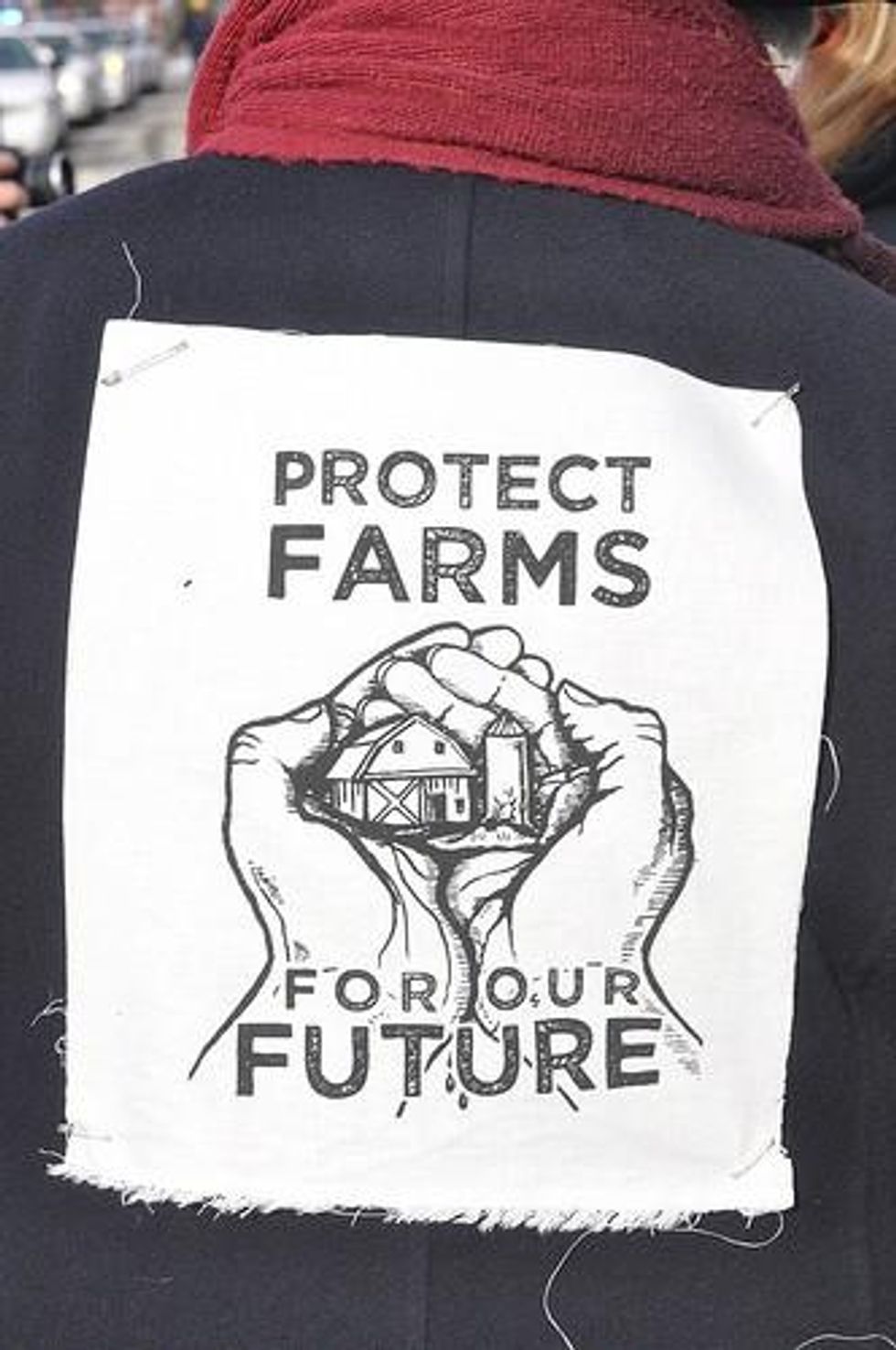

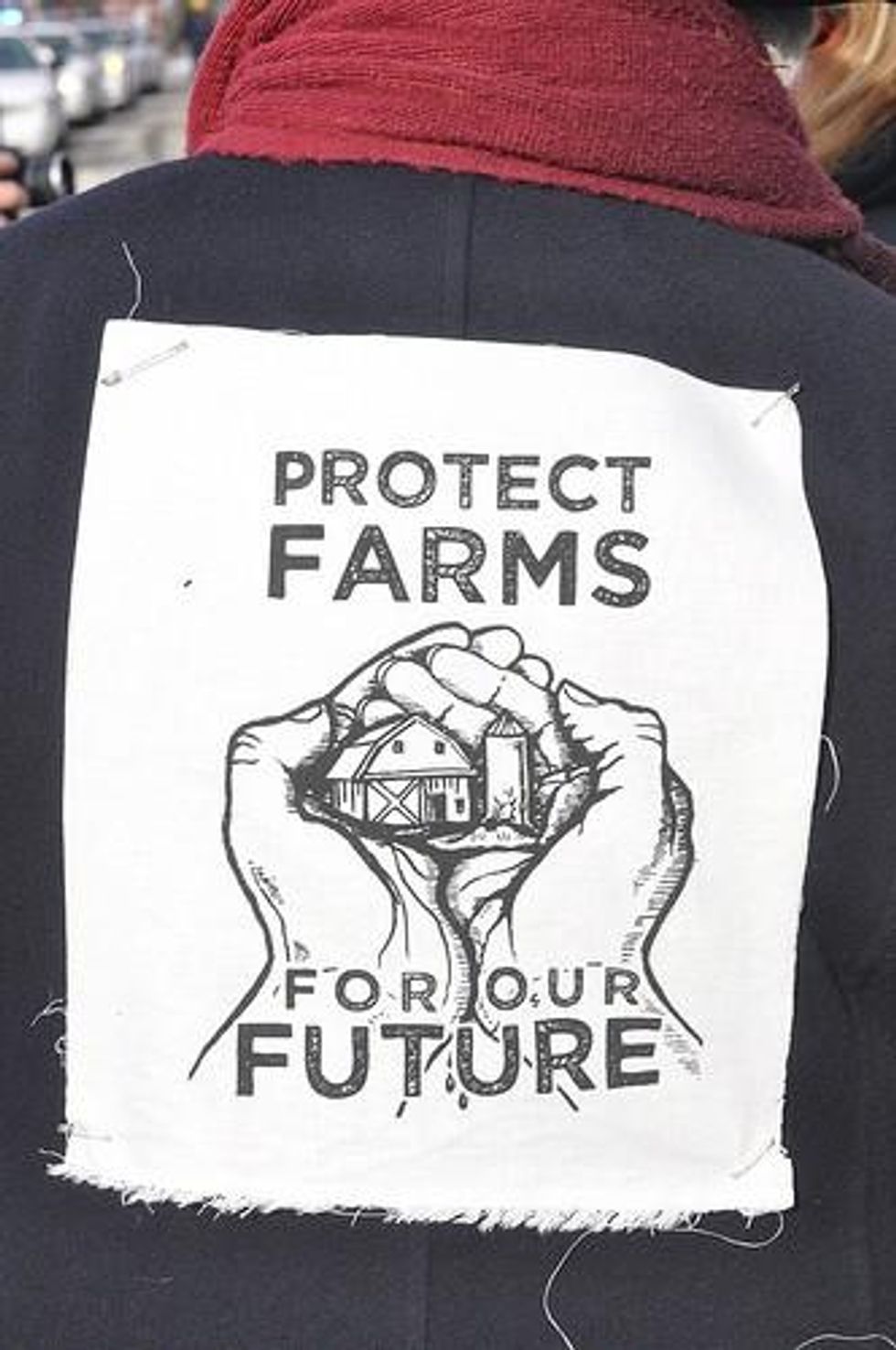

Wearing signs reading "Fracking Threatens Food" and "Protect Farms for Our Future," members of the Shadbush Environmental Justice Collective rallied behind the passionate Maggie Henry, whose organic pork and poultry farm is less than 4,000 feet from Shell's drilling site.

"People buy my food because they know that it is literally the purest that you can get. My animals run around out on ground, in pasture. They're not cooped up in cages," said Henry, who's been farming for 35 years. "Agriculture, not fracking, is the number one industry in Pennsylvania. This threatens my air, my water, my farm, my livelihood."

She's put her blood and sweat into her "beyond organic" farm, she said. "Every single penny we've earned we've invested into this farm."

With her farm, water and environment potentially ruined from Shell's fracking, Henry asked, "How is this different from Shell sticking their hand in my pocket and stealing from me?"

Devon Cohen, one of the protesters involved in the day's action, added, "Why are we willing to risk so much at the hands of multinational corporations like Shell who have shown their hand in the past as human rights abusers and irresponsible parties of environmental destruction?"

Hundreds of abandoned oil wells make the site a particularly risky place to frack, the group says. Hydro-geologist Daniel Fisher, who has studied the area, warned, "Each of these abandoned wells is a potentially direct pathway or conduit to the surface should any gas or fluids migrate upward from the wells during or after fracking."

Four of the protesters locked themselves to a large papier-mache pig named Henrietta, which blocked traffic to the site for three hours. Henrietta was made to symbolize the farm as well as "the gas industry [which] is piggish about the carbon-based fuel in the ground and are taking it at our expense," Henry said.

When the protesters locked in the "pig" agreed to disperse and avoid arrest after several hours, Shell took it. In Henry's words, "They stole Henrietta."

Nick Lubecki, one of the protesters who was locked to Henrietta, started his own farm this year in Pittsburgh and said, "It is extremely disturbing as a young farmer to have to worry about the safety of the water supply and a chaotically changing climate while these out of state drillers have the red carpet rolled out for them. In a few years the drillers will all be gone when this boom turns to bust like these things always do. I don't want to be stuck with their mess to clean up."

The group stated, "Henrietta's fate is in Shell's hands, but we're free to fight another day, our voices and our numbers are growing, and we won't stop until we win."

Maggie Henry is not about to stop fighting, either. "We're not giving up until they give up," she said.

Dear Common Dreams reader, The U.S. is on a fast track to authoritarianism like nothing I've ever seen. Meanwhile, corporate news outlets are utterly capitulating to Trump, twisting their coverage to avoid drawing his ire while lining up to stuff cash in his pockets. That's why I believe that Common Dreams is doing the best and most consequential reporting that we've ever done. Our small but mighty team is a progressive reporting powerhouse, covering the news every day that the corporate media never will. Our mission has always been simple: To inform. To inspire. And to ignite change for the common good. Now here's the key piece that I want all our readers to understand: None of this would be possible without your financial support. That's not just some fundraising cliche. It's the absolute and literal truth. We don't accept corporate advertising and never will. We don't have a paywall because we don't think people should be blocked from critical news based on their ability to pay. Everything we do is funded by the donations of readers like you. Will you donate now to help power the nonprofit, independent reporting of Common Dreams? Thank you for being a vital member of our community. Together, we can keep independent journalism alive when it’s needed most. - Craig Brown, Co-founder |

We need farms, not fracking.

This was the message from a group of concerned activists on Sunday afternoon as they blocked a Shell fracking site in Pennsylvania in part of the wave of rising actions against fossil fuels.

Wearing signs reading "Fracking Threatens Food" and "Protect Farms for Our Future," members of the Shadbush Environmental Justice Collective rallied behind the passionate Maggie Henry, whose organic pork and poultry farm is less than 4,000 feet from Shell's drilling site.

"People buy my food because they know that it is literally the purest that you can get. My animals run around out on ground, in pasture. They're not cooped up in cages," said Henry, who's been farming for 35 years. "Agriculture, not fracking, is the number one industry in Pennsylvania. This threatens my air, my water, my farm, my livelihood."

She's put her blood and sweat into her "beyond organic" farm, she said. "Every single penny we've earned we've invested into this farm."

With her farm, water and environment potentially ruined from Shell's fracking, Henry asked, "How is this different from Shell sticking their hand in my pocket and stealing from me?"

Devon Cohen, one of the protesters involved in the day's action, added, "Why are we willing to risk so much at the hands of multinational corporations like Shell who have shown their hand in the past as human rights abusers and irresponsible parties of environmental destruction?"

Hundreds of abandoned oil wells make the site a particularly risky place to frack, the group says. Hydro-geologist Daniel Fisher, who has studied the area, warned, "Each of these abandoned wells is a potentially direct pathway or conduit to the surface should any gas or fluids migrate upward from the wells during or after fracking."

Four of the protesters locked themselves to a large papier-mache pig named Henrietta, which blocked traffic to the site for three hours. Henrietta was made to symbolize the farm as well as "the gas industry [which] is piggish about the carbon-based fuel in the ground and are taking it at our expense," Henry said.

When the protesters locked in the "pig" agreed to disperse and avoid arrest after several hours, Shell took it. In Henry's words, "They stole Henrietta."

Nick Lubecki, one of the protesters who was locked to Henrietta, started his own farm this year in Pittsburgh and said, "It is extremely disturbing as a young farmer to have to worry about the safety of the water supply and a chaotically changing climate while these out of state drillers have the red carpet rolled out for them. In a few years the drillers will all be gone when this boom turns to bust like these things always do. I don't want to be stuck with their mess to clean up."

The group stated, "Henrietta's fate is in Shell's hands, but we're free to fight another day, our voices and our numbers are growing, and we won't stop until we win."

Maggie Henry is not about to stop fighting, either. "We're not giving up until they give up," she said.

We need farms, not fracking.

This was the message from a group of concerned activists on Sunday afternoon as they blocked a Shell fracking site in Pennsylvania in part of the wave of rising actions against fossil fuels.

Wearing signs reading "Fracking Threatens Food" and "Protect Farms for Our Future," members of the Shadbush Environmental Justice Collective rallied behind the passionate Maggie Henry, whose organic pork and poultry farm is less than 4,000 feet from Shell's drilling site.

"People buy my food because they know that it is literally the purest that you can get. My animals run around out on ground, in pasture. They're not cooped up in cages," said Henry, who's been farming for 35 years. "Agriculture, not fracking, is the number one industry in Pennsylvania. This threatens my air, my water, my farm, my livelihood."

She's put her blood and sweat into her "beyond organic" farm, she said. "Every single penny we've earned we've invested into this farm."

With her farm, water and environment potentially ruined from Shell's fracking, Henry asked, "How is this different from Shell sticking their hand in my pocket and stealing from me?"

Devon Cohen, one of the protesters involved in the day's action, added, "Why are we willing to risk so much at the hands of multinational corporations like Shell who have shown their hand in the past as human rights abusers and irresponsible parties of environmental destruction?"

Hundreds of abandoned oil wells make the site a particularly risky place to frack, the group says. Hydro-geologist Daniel Fisher, who has studied the area, warned, "Each of these abandoned wells is a potentially direct pathway or conduit to the surface should any gas or fluids migrate upward from the wells during or after fracking."

Four of the protesters locked themselves to a large papier-mache pig named Henrietta, which blocked traffic to the site for three hours. Henrietta was made to symbolize the farm as well as "the gas industry [which] is piggish about the carbon-based fuel in the ground and are taking it at our expense," Henry said.

When the protesters locked in the "pig" agreed to disperse and avoid arrest after several hours, Shell took it. In Henry's words, "They stole Henrietta."

Nick Lubecki, one of the protesters who was locked to Henrietta, started his own farm this year in Pittsburgh and said, "It is extremely disturbing as a young farmer to have to worry about the safety of the water supply and a chaotically changing climate while these out of state drillers have the red carpet rolled out for them. In a few years the drillers will all be gone when this boom turns to bust like these things always do. I don't want to be stuck with their mess to clean up."

The group stated, "Henrietta's fate is in Shell's hands, but we're free to fight another day, our voices and our numbers are growing, and we won't stop until we win."

Maggie Henry is not about to stop fighting, either. "We're not giving up until they give up," she said.