SUBSCRIBE TO OUR FREE NEWSLETTER

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

5

#000000

#FFFFFF

To donate by check, phone, or other method, see our More Ways to Give page.

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

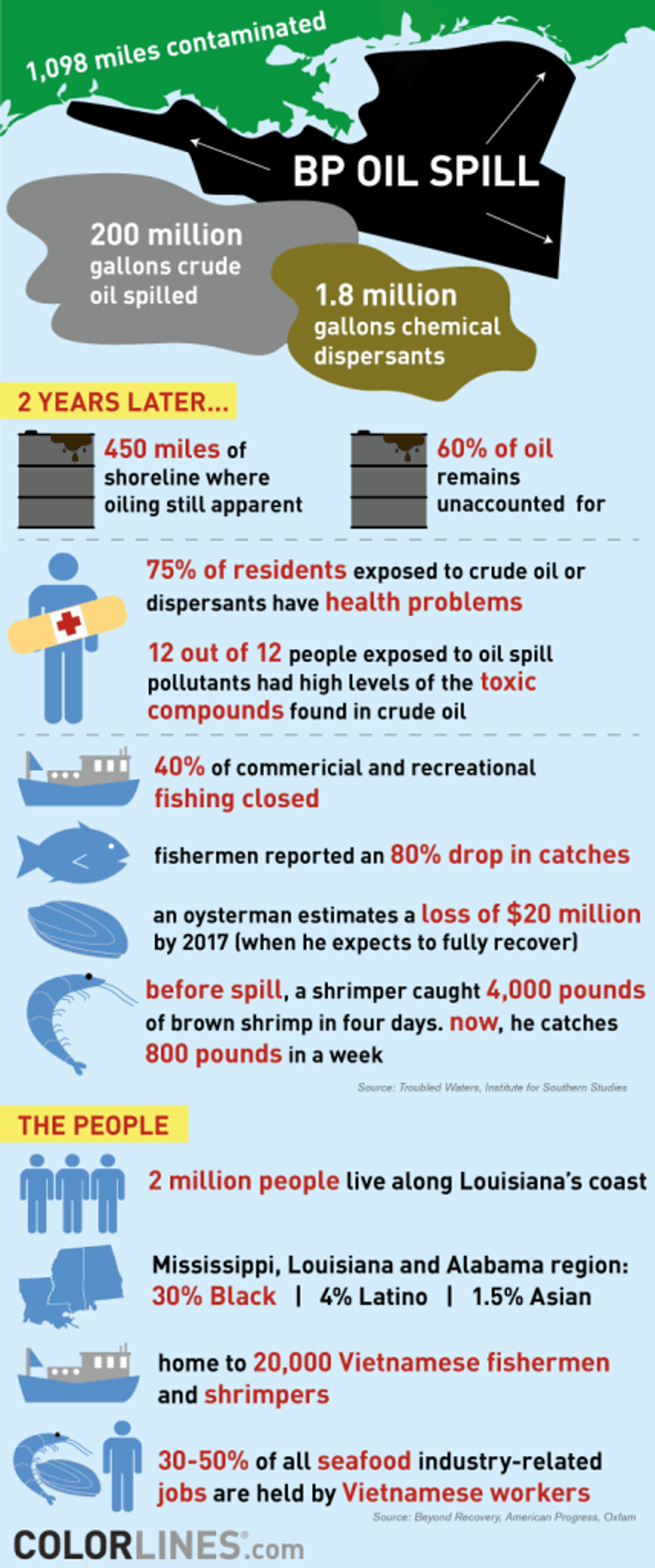

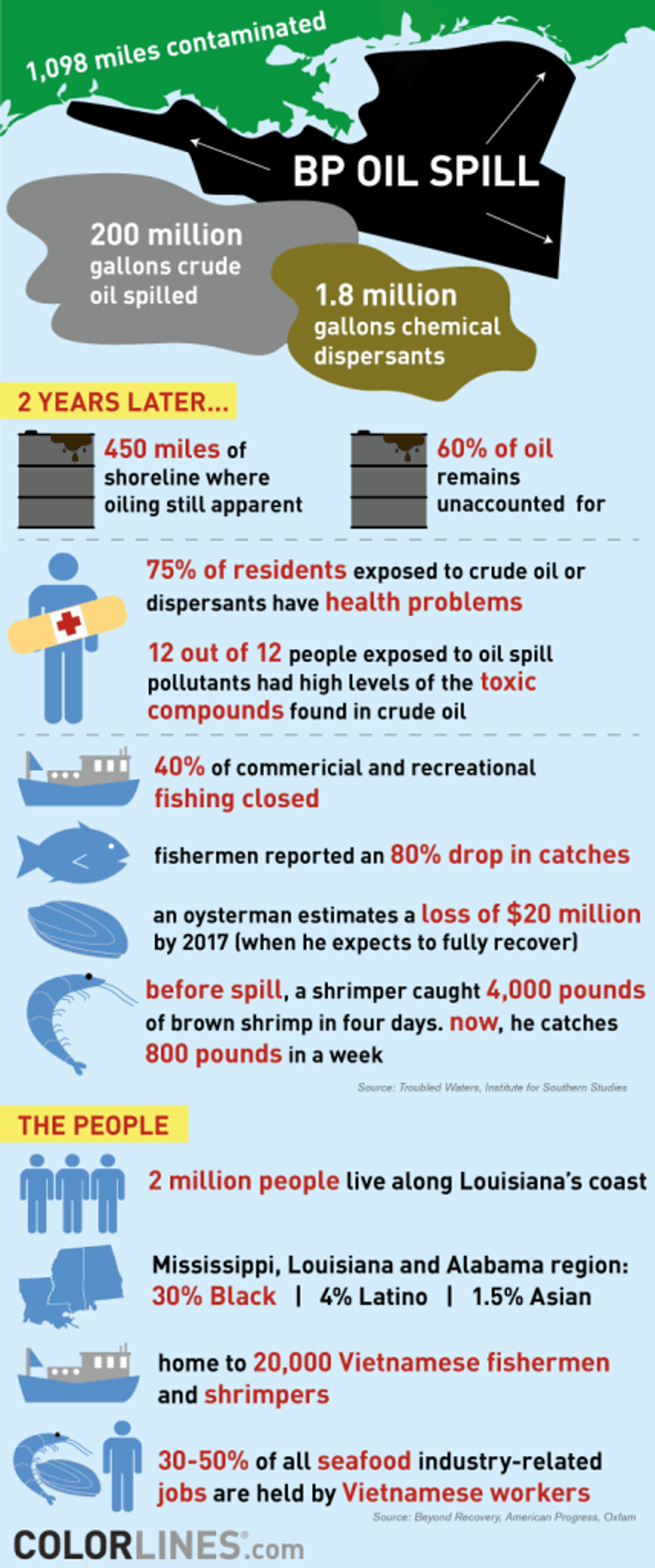

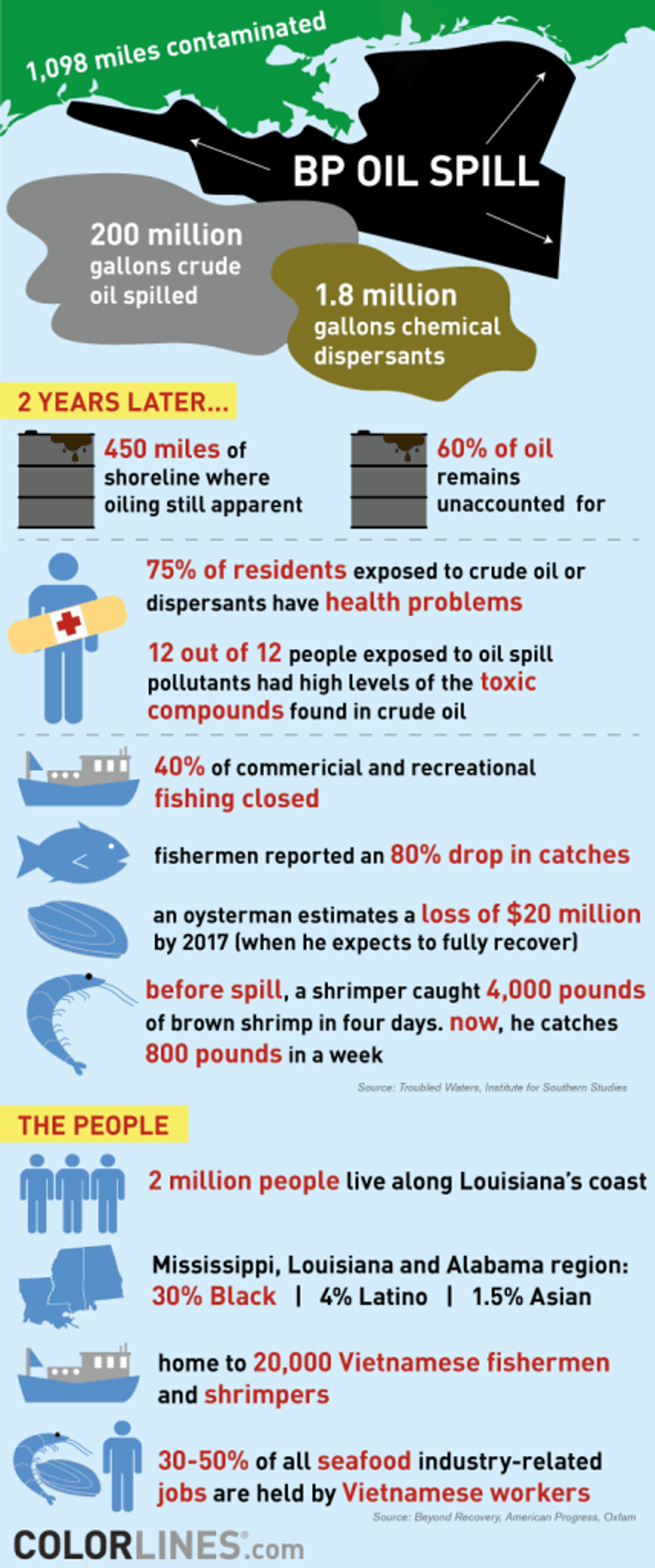

Two years since a blowout caused the BP Deepwater Horizon disaster and spewed nearly 5 million barrels of oil and more than 6 billion cubic feet of natural gas into the Gulf of Mexico, few lessons have been learned, according to various environmentalists, experts, and Gulf coast residents.

Though BP has agreed to pay billions of dollars in damages, most believe that accountability has been slim compared to the still untold damage that was caused -- much of which may not be fully realized for years to come. "BP has already tested the effectiveness of lesser consequences," says Abrahm Lustgarten, the Polk Award-winning environmental reporter for Pro Publica, "and its track record proves that the most severe punishments the courts and the United States government have been willing to mete out amount to a slap on the wrist."

Marine life in the gulf and the communities which dot its coast are rife with problems. As Phil Radford, Executive Director of Greenpeace USA and Aaron Viles, Deputy Director of Gulf Restoration Network write today: "Throughout the foodchain, warning signs are accumulating. Dolphins are sick and dying. Important forage fish are plagued with gill and developmental damage. Deepwater species like snapper have been stricken with lesions, and their reefs are losing biodiversity. Coastal communities are struggling with changes to the fisheries they rely upon. Hard-hit oyster reefs aren't coming back and sport fish like speckled trout have disappeared from some of their traditional haunts. BP's oily fingerprints continue to mar the landscape and destroy habitats."

"People should be aware that the oil is still there," Wilma Subra, a chemist who travels widely across the Gulf meeting with fishers and testing seafood and sediment samples for contamination, told freelance journalist Jordan Flaherty. Subra thinks this what is now being seen in the gulf is just the "beginning of this disaster." In every community she visits, writes Flaherty, "fishers show her shrimp born without eyes, fish with lesions, and crabs with holes in their shells." According to Subra, tarballs are still washing up on beaches across the region.

And Robert Weissman, president of Public Citizen, says that the Gulf disaster has taught many lessons, but wonders if all the right people have learned them. Among them: "Giant corporations cannot be trusted to behave responsibly, and have the ability to inflict massive damage on people and the environment. We need strong regulatory controls to curb corporate wrongdoing. We need tough penalties to punish corporate wrongdoers. There is no way to do deepwater oil drilling safely. And it is vital that citizens harmed by corporate wrongdoers maintain the right to sue to recover their losses."

And lastly, writing for The Guardian, Suzanne Goldenberg explores the question, "How much is a dolphin worth?" as she explores the dilemma of monetizing an ecosystem ravaged by man's destructive hunt for energy resources.

* * *

The New York Times: A Punishment BP Can't Pay Off by Abrahm Lustgarten

Two years after a series of gambles and ill-advised decisions on a BP drilling project led to the largest accidental oil spill in United States history and the death of 11 workers on the Deepwater Horizon oil rig, no one has been held accountable.

Sure, there have been about $8 billion in payouts and, in early March, the outlines of a civil agreement that will cost BP, the company ultimately responsible, another $7.8 billion in restitution to businesses and residents along the Gulf of Mexico. It's also true the company has paid at least $14 billion more in cleanup and other costs since the accident began on April 20, 2010, bringing the expense of this fiasco to about $30 billion for BP. These are huge numbers. But this is a huge and profitable corporation.

What is missing is the accountability that comes from real consequences: a criminal prosecution that holds responsible the individuals who gambled with the lives of BP's contractors and the ecosystem of the Gulf of Mexico. Only such an outcome can rebuild trust in an oil industry that asks for the public's faith so that it can drill more along the nation's coastlines. And perhaps only such an outcome can keep BP in line and can keep an accident like the Deepwater Horizon disaster from happening again.

BP has already tested the effectiveness of lesser consequences, and its track record proves that the most severe punishments the courts and the United States government have been willing to mete out amount to a slap on the wrist.

* * *

Greenpeace USA and the Gulf Restoration Network: BP's Gulf of Mexico Disaster: Two Years Later, Where Is The Response?

As we look back and assess where we are today, a troubling picture is emerging from the Gulf.

Throughout the foodchain, warning signs are accumulating. Dolphins are sick and dying. Important forage fish are plagued with gill and developmental damage. Deepwater species like snapper have been stricken with lesions, and their reefs are losing biodiversity. Coastal communities are struggling with changes to the fisheries they rely upon. Hard-hit oyster reefs aren't coming back and sport fish like speckled trout have disappeared from some of their traditional haunts. BP's oily fingerprints continue to mar the landscape and destroy habitats.

With these impacts already here, some scientists are alarmed by what they're finding. Unfortunately their concerns are largely drowned out by BP and the "powers that be" shouting through very large megaphones that "all is fine, BP is making it right, come and spend your money." But the truth is far different. The Gulf of Mexico, our nation's energy sacrifice zone, continues to suffer.

* * *

Public Citizen's Robert Weissman, writing at Common Dreams: The Unlearned Lessons of the BP Gulf Disaster

"In a rational world, the Deepwater Horizon horror would have been another reminder of the imperative of a rapid transition from dirty fuels to the clean energy sources of the future. Unfortunately, the power of money is having more sway over policy than the power of common sense."

--Robert Weissman, Public Citizen

When it comes to energy policy, the real lesson from the BP disaster was that deepwater drilling will inevitably lead to catastrophic spills and blowouts. The drilling technology has simply far surpassed control technologies. Since the predictable catastrophes are unacceptable, there is a good argument that deepwater drilling itself should not permitted at all. At minimum, any company undertaking a deepwater drilling project should be exposed to unlimited liability for any damage it causes; it should be required to have a spotless, company-wide safety record as a condition of receiving a lease; and it should have a well-funded, proven disaster response plan in place.

In a rational world, the Deepwater Horizon horror would have been another reminder of the imperative of a rapid transition from dirty fuels to the clean energy sources of the future. Unfortunately, the power of money is having more sway over policy than the power of common sense.

After the Deepwater Horizon explosion, the administration imposed a moratorium on deepwater drilling in the Gulf, but it was soon lifted, and deepwater drilling in the Gulf is proceeding apace. On the broader transition away from dirty energy, the administration has adopted important rules to improve auto fuel efficiency, but we are far off course if we are to avert the worst harms from catastrophic climate change.

* * *

Jordan Flaherty, also at Common Dreams: Two Years After the BP Drilling Disaster, Gulf Residents Fear for the Future

While it's too early to assess the long-term environmental impact, a host of recent studies published by the National Academy of Sciences and other respected institutions have shown troubling results. They describe mass deaths of deepwater coral, dolphins, and killifish, a small animal at the base of the Gulf food chain. "If you add them all up, it's clear the oil is still in the ecosystem, it's still having an effect," says Aaron Viles, deputy director of Gulf Restoration Network, an environmental organization active in the region.

The major class action lawsuit on behalf of communities affected by the spill has reached a proposed 7.8 billion dollar settlement, subject to approval by a judge. While this seems to have brought a certain amount of closure to the saga, environmentalists worry that any settlement is premature, saying they fear that the worst is yet to come. Pointing to the 1989 Exxon spill off the coast of Alaska, previously the largest oil spill in US waters, Viles said that it was several years before the full affect of that disaster was felt. "Four seasons after Exxon Valdez is when the herring fisheries collapsed," says Viles. "The Gulf has been a neglected ecosystem for decades - we need to be monitoring it closely."

In the aftermath of the spill, BP flooded the Gulf with nearly 2 million gallons of chemical dispersants. While BP says these chemicals broke up the oil, some scientists have said this just made it less visible, and sent the poisons deeper into the food chain.

* * *

The Guardian: Deepwater Horizon aftermath: how much is a dolphin worth?

At its most basic, the process now consuming teams of BP and government scientists and lawyers revolves around this: How much is a dolphin worth, and how exactly did it die?

"What dollar value do we place on a destroyed marsh or the loss of a spawning ground? What is the price associated with killing birds and marine mammals? Even if we were capable of meaningfully establishing a price for ecological harm, there is so much that we do not know about the harm to the Gulf of Mexico - and will not know for years - that it may never be possible to come up with an accurate natural resource damage assessment." --David Uhlmann, professor of law, Univ. of Michigan

How much lasting harm was done by the oil that still occasionally washes up on beaches, or remains as splotches on the ocean floor near the site of BP's broken well? What can be done to turn the clock back, and restore the wildlife and environment to levels that would have existed if there had not been a spill?

Wednesday's proposed $7.8bn settlement between BP and more than 100,000 people suing for economic damages due takes the oil company a step closer to consigning the spill to the past. BP is moving towards a settlement with the federal government and the governments of Louisiana and Mississippi. It could also face criminal charges.

But arguably the most difficult negotiation still lies ahead as BP and the federal government try to establish how much damage was done to the environment as a direct result of the oil spill, and how much the company will have to pay to set things right.

"It is extraordinarily difficult to monetise environmental harm. What dollar value do we place on a destroyed marsh or the loss of a spawning ground? What is the price associated with killing birds and marine mammals? Even if we were capable of meaningfully establishing a price for ecological harm, there is so much that we do not know about the harm to the Gulf of Mexico - and will not know for years - that it may never be possible to come up with an accurate natural resource damage assessment," said David Uhlmann, a law professor at the University of Michigan and a former head of the justice department's environmental crimes section.

# # #

Dear Common Dreams reader, The U.S. is on a fast track to authoritarianism like nothing I've ever seen. Meanwhile, corporate news outlets are utterly capitulating to Trump, twisting their coverage to avoid drawing his ire while lining up to stuff cash in his pockets. That's why I believe that Common Dreams is doing the best and most consequential reporting that we've ever done. Our small but mighty team is a progressive reporting powerhouse, covering the news every day that the corporate media never will. Our mission has always been simple: To inform. To inspire. And to ignite change for the common good. Now here's the key piece that I want all our readers to understand: None of this would be possible without your financial support. That's not just some fundraising cliche. It's the absolute and literal truth. We don't accept corporate advertising and never will. We don't have a paywall because we don't think people should be blocked from critical news based on their ability to pay. Everything we do is funded by the donations of readers like you. Will you donate now to help power the nonprofit, independent reporting of Common Dreams? Thank you for being a vital member of our community. Together, we can keep independent journalism alive when it’s needed most. - Craig Brown, Co-founder |

Two years since a blowout caused the BP Deepwater Horizon disaster and spewed nearly 5 million barrels of oil and more than 6 billion cubic feet of natural gas into the Gulf of Mexico, few lessons have been learned, according to various environmentalists, experts, and Gulf coast residents.

Though BP has agreed to pay billions of dollars in damages, most believe that accountability has been slim compared to the still untold damage that was caused -- much of which may not be fully realized for years to come. "BP has already tested the effectiveness of lesser consequences," says Abrahm Lustgarten, the Polk Award-winning environmental reporter for Pro Publica, "and its track record proves that the most severe punishments the courts and the United States government have been willing to mete out amount to a slap on the wrist."

Marine life in the gulf and the communities which dot its coast are rife with problems. As Phil Radford, Executive Director of Greenpeace USA and Aaron Viles, Deputy Director of Gulf Restoration Network write today: "Throughout the foodchain, warning signs are accumulating. Dolphins are sick and dying. Important forage fish are plagued with gill and developmental damage. Deepwater species like snapper have been stricken with lesions, and their reefs are losing biodiversity. Coastal communities are struggling with changes to the fisheries they rely upon. Hard-hit oyster reefs aren't coming back and sport fish like speckled trout have disappeared from some of their traditional haunts. BP's oily fingerprints continue to mar the landscape and destroy habitats."

"People should be aware that the oil is still there," Wilma Subra, a chemist who travels widely across the Gulf meeting with fishers and testing seafood and sediment samples for contamination, told freelance journalist Jordan Flaherty. Subra thinks this what is now being seen in the gulf is just the "beginning of this disaster." In every community she visits, writes Flaherty, "fishers show her shrimp born without eyes, fish with lesions, and crabs with holes in their shells." According to Subra, tarballs are still washing up on beaches across the region.

And Robert Weissman, president of Public Citizen, says that the Gulf disaster has taught many lessons, but wonders if all the right people have learned them. Among them: "Giant corporations cannot be trusted to behave responsibly, and have the ability to inflict massive damage on people and the environment. We need strong regulatory controls to curb corporate wrongdoing. We need tough penalties to punish corporate wrongdoers. There is no way to do deepwater oil drilling safely. And it is vital that citizens harmed by corporate wrongdoers maintain the right to sue to recover their losses."

And lastly, writing for The Guardian, Suzanne Goldenberg explores the question, "How much is a dolphin worth?" as she explores the dilemma of monetizing an ecosystem ravaged by man's destructive hunt for energy resources.

* * *

The New York Times: A Punishment BP Can't Pay Off by Abrahm Lustgarten

Two years after a series of gambles and ill-advised decisions on a BP drilling project led to the largest accidental oil spill in United States history and the death of 11 workers on the Deepwater Horizon oil rig, no one has been held accountable.

Sure, there have been about $8 billion in payouts and, in early March, the outlines of a civil agreement that will cost BP, the company ultimately responsible, another $7.8 billion in restitution to businesses and residents along the Gulf of Mexico. It's also true the company has paid at least $14 billion more in cleanup and other costs since the accident began on April 20, 2010, bringing the expense of this fiasco to about $30 billion for BP. These are huge numbers. But this is a huge and profitable corporation.

What is missing is the accountability that comes from real consequences: a criminal prosecution that holds responsible the individuals who gambled with the lives of BP's contractors and the ecosystem of the Gulf of Mexico. Only such an outcome can rebuild trust in an oil industry that asks for the public's faith so that it can drill more along the nation's coastlines. And perhaps only such an outcome can keep BP in line and can keep an accident like the Deepwater Horizon disaster from happening again.

BP has already tested the effectiveness of lesser consequences, and its track record proves that the most severe punishments the courts and the United States government have been willing to mete out amount to a slap on the wrist.

* * *

Greenpeace USA and the Gulf Restoration Network: BP's Gulf of Mexico Disaster: Two Years Later, Where Is The Response?

As we look back and assess where we are today, a troubling picture is emerging from the Gulf.

Throughout the foodchain, warning signs are accumulating. Dolphins are sick and dying. Important forage fish are plagued with gill and developmental damage. Deepwater species like snapper have been stricken with lesions, and their reefs are losing biodiversity. Coastal communities are struggling with changes to the fisheries they rely upon. Hard-hit oyster reefs aren't coming back and sport fish like speckled trout have disappeared from some of their traditional haunts. BP's oily fingerprints continue to mar the landscape and destroy habitats.

With these impacts already here, some scientists are alarmed by what they're finding. Unfortunately their concerns are largely drowned out by BP and the "powers that be" shouting through very large megaphones that "all is fine, BP is making it right, come and spend your money." But the truth is far different. The Gulf of Mexico, our nation's energy sacrifice zone, continues to suffer.

* * *

Public Citizen's Robert Weissman, writing at Common Dreams: The Unlearned Lessons of the BP Gulf Disaster

"In a rational world, the Deepwater Horizon horror would have been another reminder of the imperative of a rapid transition from dirty fuels to the clean energy sources of the future. Unfortunately, the power of money is having more sway over policy than the power of common sense."

--Robert Weissman, Public Citizen

When it comes to energy policy, the real lesson from the BP disaster was that deepwater drilling will inevitably lead to catastrophic spills and blowouts. The drilling technology has simply far surpassed control technologies. Since the predictable catastrophes are unacceptable, there is a good argument that deepwater drilling itself should not permitted at all. At minimum, any company undertaking a deepwater drilling project should be exposed to unlimited liability for any damage it causes; it should be required to have a spotless, company-wide safety record as a condition of receiving a lease; and it should have a well-funded, proven disaster response plan in place.

In a rational world, the Deepwater Horizon horror would have been another reminder of the imperative of a rapid transition from dirty fuels to the clean energy sources of the future. Unfortunately, the power of money is having more sway over policy than the power of common sense.

After the Deepwater Horizon explosion, the administration imposed a moratorium on deepwater drilling in the Gulf, but it was soon lifted, and deepwater drilling in the Gulf is proceeding apace. On the broader transition away from dirty energy, the administration has adopted important rules to improve auto fuel efficiency, but we are far off course if we are to avert the worst harms from catastrophic climate change.

* * *

Jordan Flaherty, also at Common Dreams: Two Years After the BP Drilling Disaster, Gulf Residents Fear for the Future

While it's too early to assess the long-term environmental impact, a host of recent studies published by the National Academy of Sciences and other respected institutions have shown troubling results. They describe mass deaths of deepwater coral, dolphins, and killifish, a small animal at the base of the Gulf food chain. "If you add them all up, it's clear the oil is still in the ecosystem, it's still having an effect," says Aaron Viles, deputy director of Gulf Restoration Network, an environmental organization active in the region.

The major class action lawsuit on behalf of communities affected by the spill has reached a proposed 7.8 billion dollar settlement, subject to approval by a judge. While this seems to have brought a certain amount of closure to the saga, environmentalists worry that any settlement is premature, saying they fear that the worst is yet to come. Pointing to the 1989 Exxon spill off the coast of Alaska, previously the largest oil spill in US waters, Viles said that it was several years before the full affect of that disaster was felt. "Four seasons after Exxon Valdez is when the herring fisheries collapsed," says Viles. "The Gulf has been a neglected ecosystem for decades - we need to be monitoring it closely."

In the aftermath of the spill, BP flooded the Gulf with nearly 2 million gallons of chemical dispersants. While BP says these chemicals broke up the oil, some scientists have said this just made it less visible, and sent the poisons deeper into the food chain.

* * *

The Guardian: Deepwater Horizon aftermath: how much is a dolphin worth?

At its most basic, the process now consuming teams of BP and government scientists and lawyers revolves around this: How much is a dolphin worth, and how exactly did it die?

"What dollar value do we place on a destroyed marsh or the loss of a spawning ground? What is the price associated with killing birds and marine mammals? Even if we were capable of meaningfully establishing a price for ecological harm, there is so much that we do not know about the harm to the Gulf of Mexico - and will not know for years - that it may never be possible to come up with an accurate natural resource damage assessment." --David Uhlmann, professor of law, Univ. of Michigan

How much lasting harm was done by the oil that still occasionally washes up on beaches, or remains as splotches on the ocean floor near the site of BP's broken well? What can be done to turn the clock back, and restore the wildlife and environment to levels that would have existed if there had not been a spill?

Wednesday's proposed $7.8bn settlement between BP and more than 100,000 people suing for economic damages due takes the oil company a step closer to consigning the spill to the past. BP is moving towards a settlement with the federal government and the governments of Louisiana and Mississippi. It could also face criminal charges.

But arguably the most difficult negotiation still lies ahead as BP and the federal government try to establish how much damage was done to the environment as a direct result of the oil spill, and how much the company will have to pay to set things right.

"It is extraordinarily difficult to monetise environmental harm. What dollar value do we place on a destroyed marsh or the loss of a spawning ground? What is the price associated with killing birds and marine mammals? Even if we were capable of meaningfully establishing a price for ecological harm, there is so much that we do not know about the harm to the Gulf of Mexico - and will not know for years - that it may never be possible to come up with an accurate natural resource damage assessment," said David Uhlmann, a law professor at the University of Michigan and a former head of the justice department's environmental crimes section.

# # #

Two years since a blowout caused the BP Deepwater Horizon disaster and spewed nearly 5 million barrels of oil and more than 6 billion cubic feet of natural gas into the Gulf of Mexico, few lessons have been learned, according to various environmentalists, experts, and Gulf coast residents.

Though BP has agreed to pay billions of dollars in damages, most believe that accountability has been slim compared to the still untold damage that was caused -- much of which may not be fully realized for years to come. "BP has already tested the effectiveness of lesser consequences," says Abrahm Lustgarten, the Polk Award-winning environmental reporter for Pro Publica, "and its track record proves that the most severe punishments the courts and the United States government have been willing to mete out amount to a slap on the wrist."

Marine life in the gulf and the communities which dot its coast are rife with problems. As Phil Radford, Executive Director of Greenpeace USA and Aaron Viles, Deputy Director of Gulf Restoration Network write today: "Throughout the foodchain, warning signs are accumulating. Dolphins are sick and dying. Important forage fish are plagued with gill and developmental damage. Deepwater species like snapper have been stricken with lesions, and their reefs are losing biodiversity. Coastal communities are struggling with changes to the fisheries they rely upon. Hard-hit oyster reefs aren't coming back and sport fish like speckled trout have disappeared from some of their traditional haunts. BP's oily fingerprints continue to mar the landscape and destroy habitats."

"People should be aware that the oil is still there," Wilma Subra, a chemist who travels widely across the Gulf meeting with fishers and testing seafood and sediment samples for contamination, told freelance journalist Jordan Flaherty. Subra thinks this what is now being seen in the gulf is just the "beginning of this disaster." In every community she visits, writes Flaherty, "fishers show her shrimp born without eyes, fish with lesions, and crabs with holes in their shells." According to Subra, tarballs are still washing up on beaches across the region.

And Robert Weissman, president of Public Citizen, says that the Gulf disaster has taught many lessons, but wonders if all the right people have learned them. Among them: "Giant corporations cannot be trusted to behave responsibly, and have the ability to inflict massive damage on people and the environment. We need strong regulatory controls to curb corporate wrongdoing. We need tough penalties to punish corporate wrongdoers. There is no way to do deepwater oil drilling safely. And it is vital that citizens harmed by corporate wrongdoers maintain the right to sue to recover their losses."

And lastly, writing for The Guardian, Suzanne Goldenberg explores the question, "How much is a dolphin worth?" as she explores the dilemma of monetizing an ecosystem ravaged by man's destructive hunt for energy resources.

* * *

The New York Times: A Punishment BP Can't Pay Off by Abrahm Lustgarten

Two years after a series of gambles and ill-advised decisions on a BP drilling project led to the largest accidental oil spill in United States history and the death of 11 workers on the Deepwater Horizon oil rig, no one has been held accountable.

Sure, there have been about $8 billion in payouts and, in early March, the outlines of a civil agreement that will cost BP, the company ultimately responsible, another $7.8 billion in restitution to businesses and residents along the Gulf of Mexico. It's also true the company has paid at least $14 billion more in cleanup and other costs since the accident began on April 20, 2010, bringing the expense of this fiasco to about $30 billion for BP. These are huge numbers. But this is a huge and profitable corporation.

What is missing is the accountability that comes from real consequences: a criminal prosecution that holds responsible the individuals who gambled with the lives of BP's contractors and the ecosystem of the Gulf of Mexico. Only such an outcome can rebuild trust in an oil industry that asks for the public's faith so that it can drill more along the nation's coastlines. And perhaps only such an outcome can keep BP in line and can keep an accident like the Deepwater Horizon disaster from happening again.

BP has already tested the effectiveness of lesser consequences, and its track record proves that the most severe punishments the courts and the United States government have been willing to mete out amount to a slap on the wrist.

* * *

Greenpeace USA and the Gulf Restoration Network: BP's Gulf of Mexico Disaster: Two Years Later, Where Is The Response?

As we look back and assess where we are today, a troubling picture is emerging from the Gulf.

Throughout the foodchain, warning signs are accumulating. Dolphins are sick and dying. Important forage fish are plagued with gill and developmental damage. Deepwater species like snapper have been stricken with lesions, and their reefs are losing biodiversity. Coastal communities are struggling with changes to the fisheries they rely upon. Hard-hit oyster reefs aren't coming back and sport fish like speckled trout have disappeared from some of their traditional haunts. BP's oily fingerprints continue to mar the landscape and destroy habitats.

With these impacts already here, some scientists are alarmed by what they're finding. Unfortunately their concerns are largely drowned out by BP and the "powers that be" shouting through very large megaphones that "all is fine, BP is making it right, come and spend your money." But the truth is far different. The Gulf of Mexico, our nation's energy sacrifice zone, continues to suffer.

* * *

Public Citizen's Robert Weissman, writing at Common Dreams: The Unlearned Lessons of the BP Gulf Disaster

"In a rational world, the Deepwater Horizon horror would have been another reminder of the imperative of a rapid transition from dirty fuels to the clean energy sources of the future. Unfortunately, the power of money is having more sway over policy than the power of common sense."

--Robert Weissman, Public Citizen

When it comes to energy policy, the real lesson from the BP disaster was that deepwater drilling will inevitably lead to catastrophic spills and blowouts. The drilling technology has simply far surpassed control technologies. Since the predictable catastrophes are unacceptable, there is a good argument that deepwater drilling itself should not permitted at all. At minimum, any company undertaking a deepwater drilling project should be exposed to unlimited liability for any damage it causes; it should be required to have a spotless, company-wide safety record as a condition of receiving a lease; and it should have a well-funded, proven disaster response plan in place.

In a rational world, the Deepwater Horizon horror would have been another reminder of the imperative of a rapid transition from dirty fuels to the clean energy sources of the future. Unfortunately, the power of money is having more sway over policy than the power of common sense.

After the Deepwater Horizon explosion, the administration imposed a moratorium on deepwater drilling in the Gulf, but it was soon lifted, and deepwater drilling in the Gulf is proceeding apace. On the broader transition away from dirty energy, the administration has adopted important rules to improve auto fuel efficiency, but we are far off course if we are to avert the worst harms from catastrophic climate change.

* * *

Jordan Flaherty, also at Common Dreams: Two Years After the BP Drilling Disaster, Gulf Residents Fear for the Future

While it's too early to assess the long-term environmental impact, a host of recent studies published by the National Academy of Sciences and other respected institutions have shown troubling results. They describe mass deaths of deepwater coral, dolphins, and killifish, a small animal at the base of the Gulf food chain. "If you add them all up, it's clear the oil is still in the ecosystem, it's still having an effect," says Aaron Viles, deputy director of Gulf Restoration Network, an environmental organization active in the region.

The major class action lawsuit on behalf of communities affected by the spill has reached a proposed 7.8 billion dollar settlement, subject to approval by a judge. While this seems to have brought a certain amount of closure to the saga, environmentalists worry that any settlement is premature, saying they fear that the worst is yet to come. Pointing to the 1989 Exxon spill off the coast of Alaska, previously the largest oil spill in US waters, Viles said that it was several years before the full affect of that disaster was felt. "Four seasons after Exxon Valdez is when the herring fisheries collapsed," says Viles. "The Gulf has been a neglected ecosystem for decades - we need to be monitoring it closely."

In the aftermath of the spill, BP flooded the Gulf with nearly 2 million gallons of chemical dispersants. While BP says these chemicals broke up the oil, some scientists have said this just made it less visible, and sent the poisons deeper into the food chain.

* * *

The Guardian: Deepwater Horizon aftermath: how much is a dolphin worth?

At its most basic, the process now consuming teams of BP and government scientists and lawyers revolves around this: How much is a dolphin worth, and how exactly did it die?

"What dollar value do we place on a destroyed marsh or the loss of a spawning ground? What is the price associated with killing birds and marine mammals? Even if we were capable of meaningfully establishing a price for ecological harm, there is so much that we do not know about the harm to the Gulf of Mexico - and will not know for years - that it may never be possible to come up with an accurate natural resource damage assessment." --David Uhlmann, professor of law, Univ. of Michigan

How much lasting harm was done by the oil that still occasionally washes up on beaches, or remains as splotches on the ocean floor near the site of BP's broken well? What can be done to turn the clock back, and restore the wildlife and environment to levels that would have existed if there had not been a spill?

Wednesday's proposed $7.8bn settlement between BP and more than 100,000 people suing for economic damages due takes the oil company a step closer to consigning the spill to the past. BP is moving towards a settlement with the federal government and the governments of Louisiana and Mississippi. It could also face criminal charges.

But arguably the most difficult negotiation still lies ahead as BP and the federal government try to establish how much damage was done to the environment as a direct result of the oil spill, and how much the company will have to pay to set things right.

"It is extraordinarily difficult to monetise environmental harm. What dollar value do we place on a destroyed marsh or the loss of a spawning ground? What is the price associated with killing birds and marine mammals? Even if we were capable of meaningfully establishing a price for ecological harm, there is so much that we do not know about the harm to the Gulf of Mexico - and will not know for years - that it may never be possible to come up with an accurate natural resource damage assessment," said David Uhlmann, a law professor at the University of Michigan and a former head of the justice department's environmental crimes section.

# # #