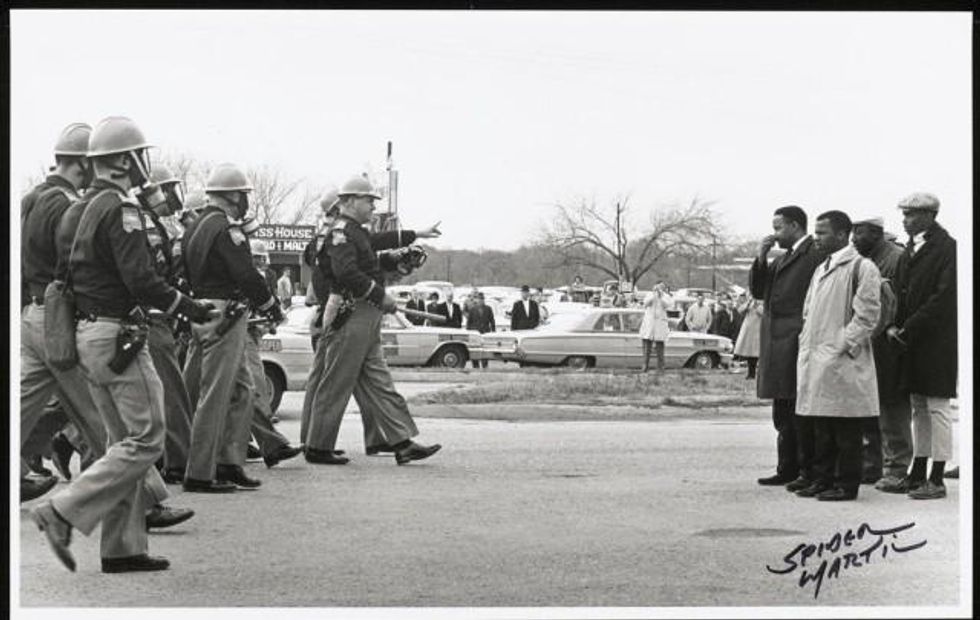

The Edmund Pettus Bridge

In an enduring tribute to his resolute work "to save America from herself," Georgia officials this week moved to replace hate with hope by approving a memorial to civil rights icon John Lewis in a Decatur square where an obelisk honoring Confederate soldiers, aptly titled The Lost Cause, stood for over 100 years. The unanimous vote by DeKalb County commissioners marked the culmination of a months-long effort by a Commemorative Task Force to determine how best to honor Lewis's extraordinary life and civil rights legacy. Lewis died in July at age 80 from complications of pancreatic cancer, having battled his last few months through "good days and days not so good." Born in 1940, he was the third of 10 children born to Jim-Crow-era Alabama sharecroppers. After meeting and being inspired by Martin Luther King at 18 - "Dr. King was speaking to me" - he found his spiritual and political home in the civil rights movement, quickly going on to become chairman of SNCC, one of the "Big Six" leaders who planned the 1963 March on Washington, and, at 23, its youngest speaker, declaring to massive crowds at the Lincoln Memorial, "We want our freedom and we want it now!" In 1965, he led the seminal march at Selma's Edmund Pettus Bridge that helped prompt passage of the Voting Rights Act. Arrested 40-plus times, Lewis served over 30 years in Congress, representing Georgia's Fifth District and becoming known as the ever-honorable "conscience of Congress." A towering figure of fierce moral clarity, he remained true to his principles till the end; weeks before his death, he visited Black Lives Matter protests in D.C. to support the lifelong activism he famously dubbed "good trouble."

To many in Decatur, a progressive suburb of Atlanta, it's deeply gratifying that a beloved civil rights luminary who championed voting rights will supplant the much-reviled, oft-graffitied, 30-foot Lost Cause, erected by the United Daughters of the Confederacy before the County Courthouse in 1908 - the same year Georgia's legislators ratified an amendment to prevent African-Americans from voting. In 2017, after home-grown Nazis marched in Charlottesville, residents delivered a petition to city officials urging the monument be removed as "a symbol of white nationalism." In June, amidst BLM protests in the wake of George Floyd's murder, a judge finally ordered its removal as "a public nuisance." Decatur officials consider the historic courthouse site, encompassing both Lewis' district and the county seat, "the most fitting" to honor their own "American hero." "John was a giant of a man, with a humble heart," said one. "He met no strangers, and he truly was a man who loved the people." The Decatur-based Beacon Hill Alliance for Human Rights has proposed the statue depict a young Lewis, in the trench coat and backpack he wore on Selma's Bloody Sunday, to symbolize the "many young people (who) have been a catalyst for change in the world." Still, for some it was the elder Lewis' steadfast perseverance, his decades-long instinct "to be vigilant, but stubbornly hopeful," that was most inspiring. In an interview a scant month before his death, Lewis recalled his long, righteous struggle to create "what we called the loving community...to redeem the soul of America," arguing even through Trumpian times, "We all live in the same house." Now he will grace the heart of Decatur, a reminder, as he long asserted, "There can be no turning back, there can be no giving up."

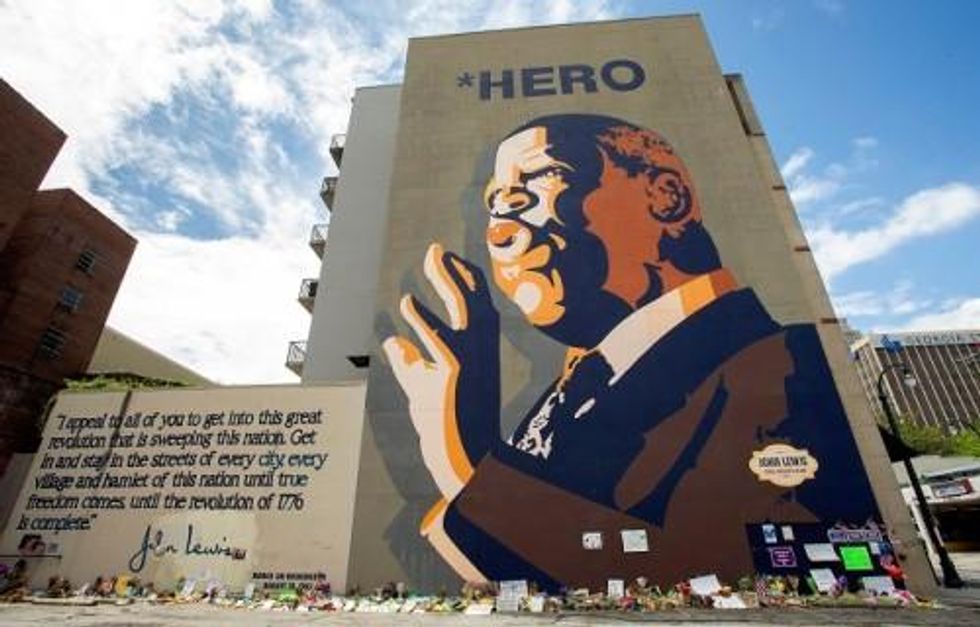

Lewis mural painted by Sean Schwab in Atlanta's Sweet Auburn neighborhood. Photo by Dean Hesse.

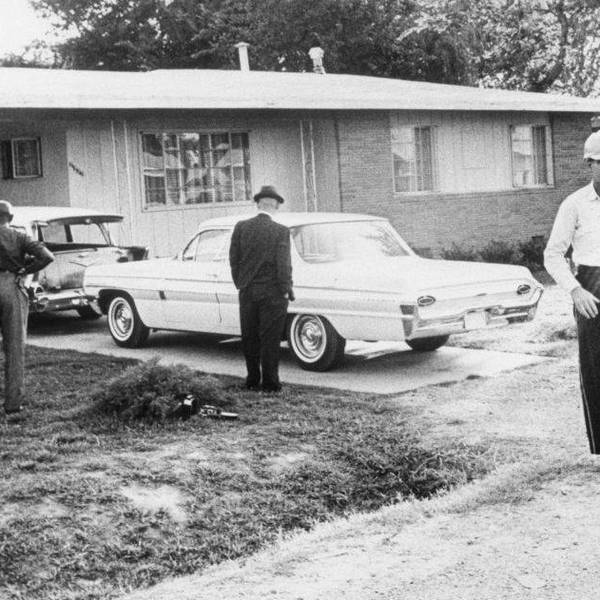

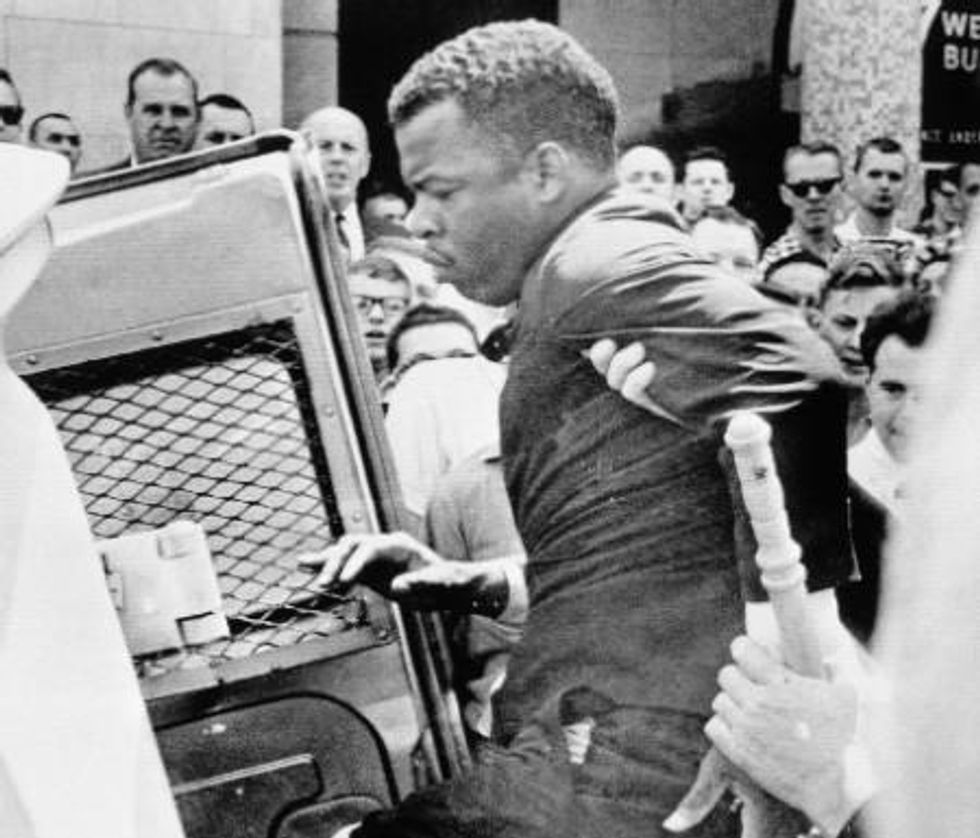

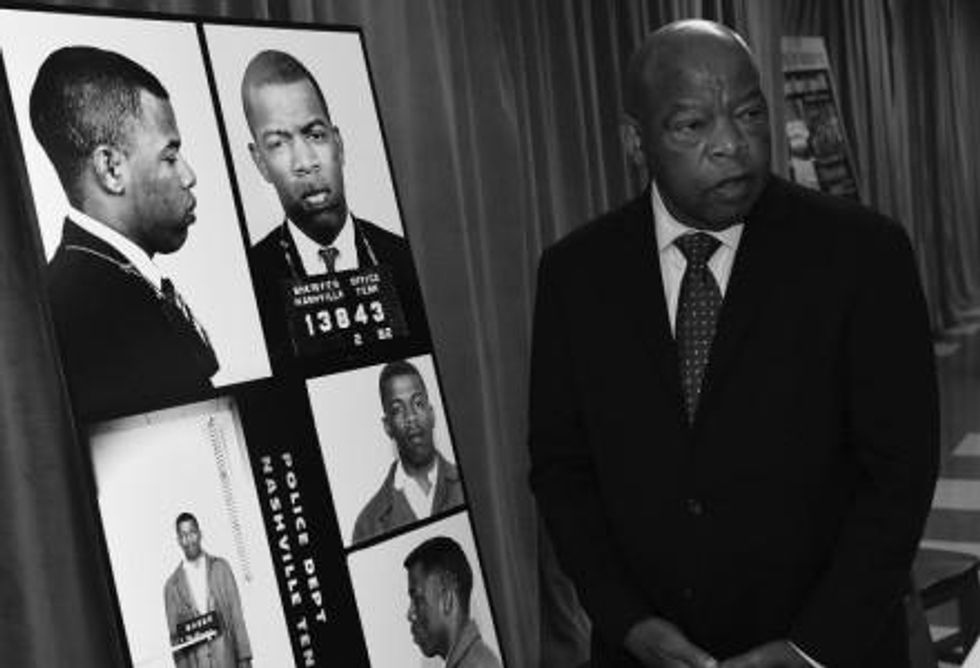

Nashville arrest

AP photo

Nashville arrest records unearthed from a 1963 lunch counter sit-in as chairman of SNCC. They were presented to Lewis in an emotional ceremony when he visited the city to get an award for his acclaimed autobiographical graphic novel trilogy March, which also won a 2016 National Book Award for Young People's Literature. Getty Image

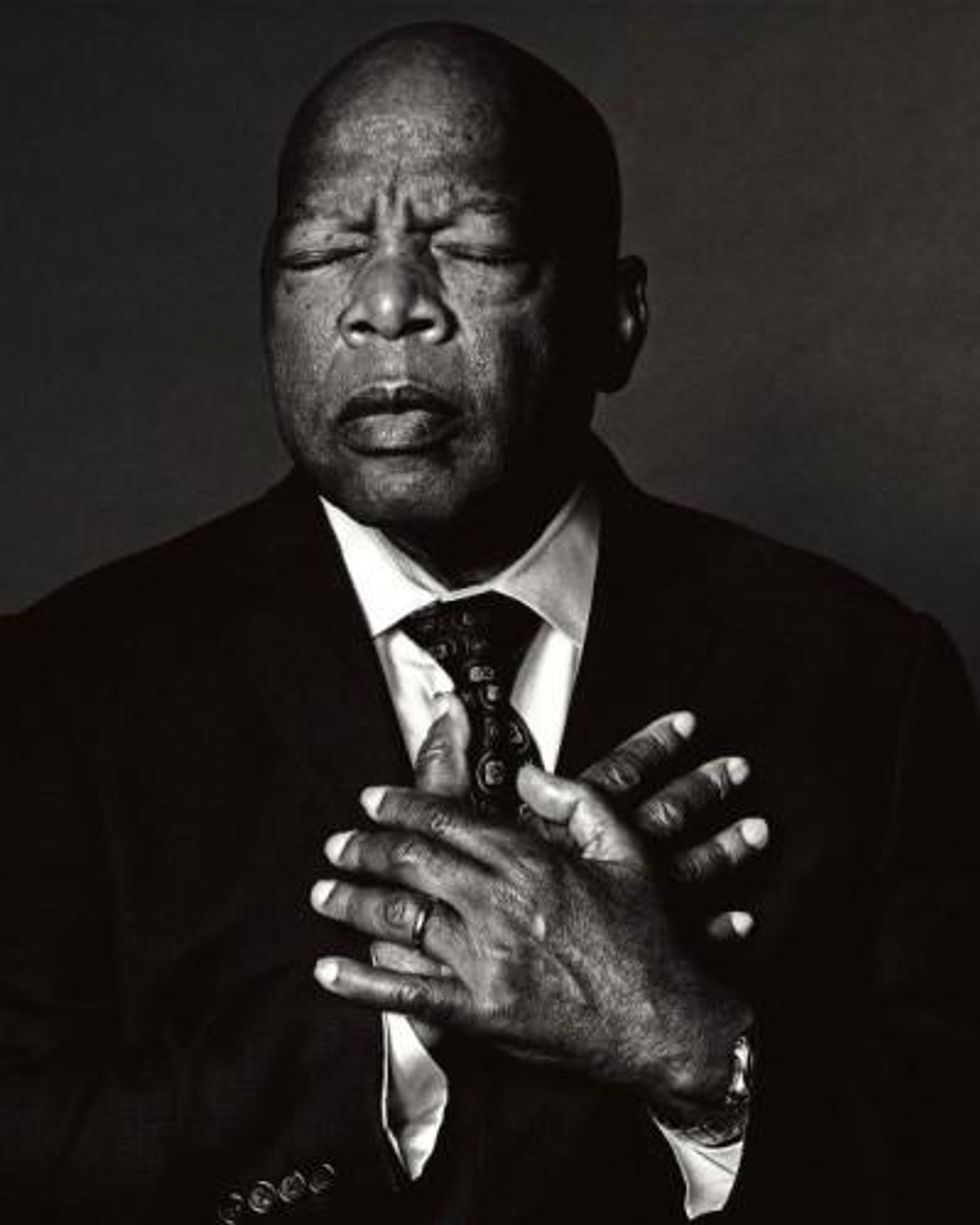

Photo by Michael Avedon