SUBSCRIBE TO OUR FREE NEWSLETTER

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

5

#000000

#FFFFFF

To donate by check, phone, or other method, see our More Ways to Give page.

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

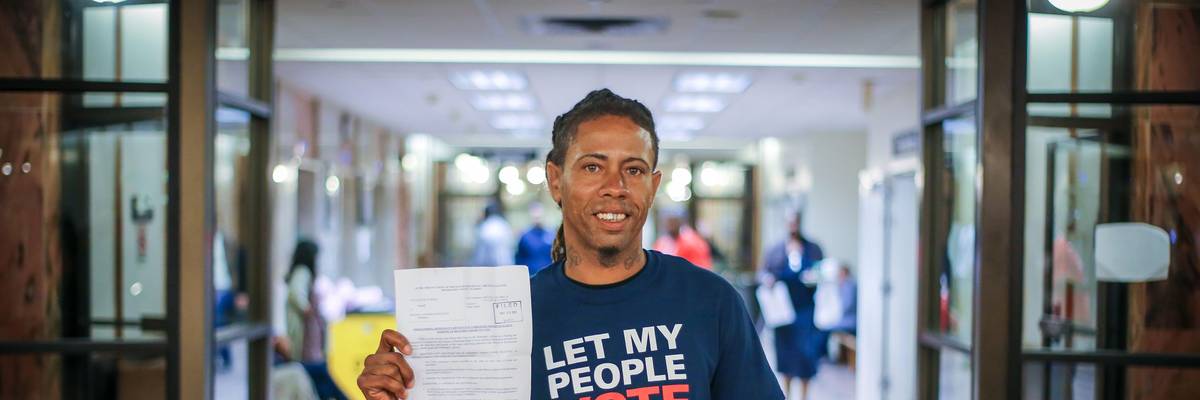

Michael Monfluery, 38, who has never been eligible to vote, stands in a courthouse corridor following special court hearing aimed at restoring the right to vote under Florida's amendment 4 in a Miami-Dade County courtroom on November 8, 2019, in Miami, Florida. - Eighteen former felons saw their right to vote restored, allowing them to cast their ballot in the 2020 election. (Photo by ZAK BENNETT/AFP via Getty Images)

In recent years, voting rights advocates and state lawmakers have made significant strides in restoring voting rights to U.S. citizens with felony convictions.

In the 2020 U.S. presidential election, 5.17 million people were disenfranchised due to a felony conviction, according to the Sentencing Project -- 15% fewer than in 2016, as states implemented measures to restore voting rights to people with felony convictions who served their sentences. From 2016 to 2020, at least 13 states expanded to some degree voting rights for ex-felons, including the Southern states of Alabama, Florida, Kentucky, Louisiana, and Virginia.

Historians point out that felony disenfranchisement laws are rooted in the Jim Crow era and were implemented to suppress Black electoral power. After Black men were granted the right to vote in 1870, Southern states started to adopt such laws, along with others designed to prevent Black voters from casting a ballot. According to a 2003 study from scholars at the University of Minnesota and Northwestern University, the greater a state's nonwhite prison population, the more likely it was to adopt stringent felony disenfranchisement laws. Currently, 11 states still permanently disenfranchise at least some individuals from voting due to past criminal convictions, including five in the South: Alabama, Florida, Kentucky, Mississippi, and Tennessee.

These laws continue to have a disproportionate impact on Black people and communities of color. For example, as of 2020 more than one in seven Black adults were disenfranchised in six of the 13 Southern states -- Alabama, Florida, Kentucky, Mississippi, Tennessee, and Virginia.

With the midterm elections now underway, efforts are continuing in several Southern states to restore voting rights to people with felony convictions who've completed their sentences. Those efforts could potentially have some impact on the outcome of the elections: A 2019 study found that laws re-enfranchising ex-felons had a "positive, but not statistically significant, effect" on the vote share of Democratic candidates and turnout rates of minority voters in U.S. House elections.

Voting rights activists had pressed Congress to pass federal legislation to restore the franchise to ex-felons nationwide. But in January, the Democrats' far-reaching pro-democracy bill failed to garner enough votes to overcome threats of a Republican filibuster. The measure would have established one national standard for restoring rights by mandating that a person's right to vote could not be "denied or abridged because that individual has been convicted of a criminal offense unless such individual is serving a felony sentence in a correctional institution or facility at the time of the election." As a consequence, the movement to restore ex-felons' voting rights is now focusing on the states.

A court challenge in Mississippi

Earlier this year in Mississippi, the legislature passed Senate Bill 2536, a Republican-sponsored proposal that would have made it easier for individuals with felony convictions to regain their voting rights after completing their sentences. However, Gov. Tate Reeves (R) vetoed it. Mississippi remains among the fewer than 10 states nationwide that do not automatically restore voting rights to people convicted of felonies after they complete their sentence. The law derives from the state's constitutional convention of 1890 that sought to develop a plan to block Black people from voting. State officials adopted a provision that barred voting by people convicted of specific felonies -- and the crimes they chose to include were those they thought Black people were more likely to commit. There are currently 23 specific crimes that result in a lifelong voting ban in the state.

Under current Mississippi law, voting rights can be restored only by a gubernatorial pardon or legislation that passes both the state House and Senate by a two-thirds vote. Mississippi is the only state in the nation that typically requires legislative action to restore ex-felons' voting rights. During the 2022 state legislative session, lawmakers took action to restore voting rights to just five people, while only 185 Mississippians convicted of felonies have had their voting rights restored by the legislature since 1997, The Guardian reports. And 2018 data shows that while Black people account for just 36% of the state's population they make up 61% of Mississippians who have lost their right to vote due to a felony conviction.

The Mississippi Constitution's felony disenfranchisement provision is currently being challenged in federal court for its racist intent by a 2017 lawsuit filed by the Mississippi Center for Justice on behalf of Roy Harness and Kamal Karriem. Last year a three-judge panel of the conservative 5th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals rejected efforts to continue the lawsuit, but then last June the court agreed to rehear the case, and there were oral arguments in September. A ruling is expected in the coming months. The decision will determine the constitutionality of the disenfranchisement provisions and the fate of former felons waiting to regain their right to vote

"At a time when most states have repealed their disfranchisement laws, it is time to remove from Mississippi's constitution this backward provision that was enacted with such a vicious purpose," said Vangela M. Wade, president and CEO of Mississippi Center for Justice.

Another lawsuit in North Carolina

In North Carolina, the fight for ex-felon voting rights is also being waged in the courts. In March, a three-judge Superior Court panel struck down a 1973 law that prevented people from voting while serving active sentences -- including when they are on probation or parole.

The lawsuit was originally filed against Republican legislative leaders in 2019 on behalf of several voting and civil rights groups including Community Success Initiative, Justice Served NC, the North Carolina NAACP, Wash Away Unemployment, and individuals convicted of felonies. "People who work, live, and pay taxes in our communities should not have their voices & votes silenced due to a previous felony conviction," tweeted Forward Justice, a Durham-based legal organization representing the plaintiffs.

The court found that the law was rooted in 19th-century white supremacy and had a disparate impact on Black people, who make up 20% of the state's voting age population but 40% of those who lost their voting rights for a felony conviction, according to 2018 data referenced in the lawsuit. The panel ruled that individuals who have completed their active prison time will be able to vote in the November elections. The decision could affect roughly 56,000 people, according to court testimony.

However, Republican state House Speaker Tim Moore and state Senate leader Phil Berger appealed the decision to the Republican-controlled North Carolina Court of Appeals. But last month, the Democratic-controlled state Supreme Court announced that it would take over the lawsuit per a request from the plaintiffs rather than wait for the Court of Appeals to rule. The move makes it more likely that the case will be resolved before the November general election.

A proposed amendment in Virginia

And in Virginia, Gov. Glenn Youngkin, a Republican, announced last month that he had restored voting rights to 3,496 individuals with felony convictions. "Individuals with their rights restored come from every walk of life and are eager to provide for themselves, their families and put the past behind them for a better tomorrow," Youngkin said. Though Virginia is among the states that permanently bar people with felony convictions from voting, the state constitution gives the governor the ability to restore voting rights to those who complete their criminal sentences. Both Republican and Democratic governors in Virginia have led rights restoration efforts for ex-felons in recent years.

Last year a constitutional amendment that would have automatically restored voting rights for felons upon completion of their incarceration. The bill passed the General Assembly last year, when Democrats led both the state House and Senate, but it was thwarted once Republicans took control of the House -- despite support across the political spectrum from groups including the American Conservative Union, Americans for Prosperity Virginia, the ACLU of Virginia, the Legal Aid Justice Center, the League of Women Voters of Virginia, the Virginia Interfaith Center for Public Policy, the Virginia Catholic Conference, and the Virginia NAACP.

Because Virginia law requires a proposed constitutional amendment to be passed by the General Assembly for two successive years before going to voters, the earliest a new version could possibly be implemented would be the fall of 2024. For now, former felons seeking to regain their voting rights will have to rely on Youngkin, who has yet to state his position on the proposed amendment.

Dear Common Dreams reader, The U.S. is on a fast track to authoritarianism like nothing I've ever seen. Meanwhile, corporate news outlets are utterly capitulating to Trump, twisting their coverage to avoid drawing his ire while lining up to stuff cash in his pockets. That's why I believe that Common Dreams is doing the best and most consequential reporting that we've ever done. Our small but mighty team is a progressive reporting powerhouse, covering the news every day that the corporate media never will. Our mission has always been simple: To inform. To inspire. And to ignite change for the common good. Now here's the key piece that I want all our readers to understand: None of this would be possible without your financial support. That's not just some fundraising cliche. It's the absolute and literal truth. We don't accept corporate advertising and never will. We don't have a paywall because we don't think people should be blocked from critical news based on their ability to pay. Everything we do is funded by the donations of readers like you. Will you donate now to help power the nonprofit, independent reporting of Common Dreams? Thank you for being a vital member of our community. Together, we can keep independent journalism alive when it’s needed most. - Craig Brown, Co-founder |

In recent years, voting rights advocates and state lawmakers have made significant strides in restoring voting rights to U.S. citizens with felony convictions.

In the 2020 U.S. presidential election, 5.17 million people were disenfranchised due to a felony conviction, according to the Sentencing Project -- 15% fewer than in 2016, as states implemented measures to restore voting rights to people with felony convictions who served their sentences. From 2016 to 2020, at least 13 states expanded to some degree voting rights for ex-felons, including the Southern states of Alabama, Florida, Kentucky, Louisiana, and Virginia.

Historians point out that felony disenfranchisement laws are rooted in the Jim Crow era and were implemented to suppress Black electoral power. After Black men were granted the right to vote in 1870, Southern states started to adopt such laws, along with others designed to prevent Black voters from casting a ballot. According to a 2003 study from scholars at the University of Minnesota and Northwestern University, the greater a state's nonwhite prison population, the more likely it was to adopt stringent felony disenfranchisement laws. Currently, 11 states still permanently disenfranchise at least some individuals from voting due to past criminal convictions, including five in the South: Alabama, Florida, Kentucky, Mississippi, and Tennessee.

These laws continue to have a disproportionate impact on Black people and communities of color. For example, as of 2020 more than one in seven Black adults were disenfranchised in six of the 13 Southern states -- Alabama, Florida, Kentucky, Mississippi, Tennessee, and Virginia.

With the midterm elections now underway, efforts are continuing in several Southern states to restore voting rights to people with felony convictions who've completed their sentences. Those efforts could potentially have some impact on the outcome of the elections: A 2019 study found that laws re-enfranchising ex-felons had a "positive, but not statistically significant, effect" on the vote share of Democratic candidates and turnout rates of minority voters in U.S. House elections.

Voting rights activists had pressed Congress to pass federal legislation to restore the franchise to ex-felons nationwide. But in January, the Democrats' far-reaching pro-democracy bill failed to garner enough votes to overcome threats of a Republican filibuster. The measure would have established one national standard for restoring rights by mandating that a person's right to vote could not be "denied or abridged because that individual has been convicted of a criminal offense unless such individual is serving a felony sentence in a correctional institution or facility at the time of the election." As a consequence, the movement to restore ex-felons' voting rights is now focusing on the states.

A court challenge in Mississippi

Earlier this year in Mississippi, the legislature passed Senate Bill 2536, a Republican-sponsored proposal that would have made it easier for individuals with felony convictions to regain their voting rights after completing their sentences. However, Gov. Tate Reeves (R) vetoed it. Mississippi remains among the fewer than 10 states nationwide that do not automatically restore voting rights to people convicted of felonies after they complete their sentence. The law derives from the state's constitutional convention of 1890 that sought to develop a plan to block Black people from voting. State officials adopted a provision that barred voting by people convicted of specific felonies -- and the crimes they chose to include were those they thought Black people were more likely to commit. There are currently 23 specific crimes that result in a lifelong voting ban in the state.

Under current Mississippi law, voting rights can be restored only by a gubernatorial pardon or legislation that passes both the state House and Senate by a two-thirds vote. Mississippi is the only state in the nation that typically requires legislative action to restore ex-felons' voting rights. During the 2022 state legislative session, lawmakers took action to restore voting rights to just five people, while only 185 Mississippians convicted of felonies have had their voting rights restored by the legislature since 1997, The Guardian reports. And 2018 data shows that while Black people account for just 36% of the state's population they make up 61% of Mississippians who have lost their right to vote due to a felony conviction.

The Mississippi Constitution's felony disenfranchisement provision is currently being challenged in federal court for its racist intent by a 2017 lawsuit filed by the Mississippi Center for Justice on behalf of Roy Harness and Kamal Karriem. Last year a three-judge panel of the conservative 5th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals rejected efforts to continue the lawsuit, but then last June the court agreed to rehear the case, and there were oral arguments in September. A ruling is expected in the coming months. The decision will determine the constitutionality of the disenfranchisement provisions and the fate of former felons waiting to regain their right to vote

"At a time when most states have repealed their disfranchisement laws, it is time to remove from Mississippi's constitution this backward provision that was enacted with such a vicious purpose," said Vangela M. Wade, president and CEO of Mississippi Center for Justice.

Another lawsuit in North Carolina

In North Carolina, the fight for ex-felon voting rights is also being waged in the courts. In March, a three-judge Superior Court panel struck down a 1973 law that prevented people from voting while serving active sentences -- including when they are on probation or parole.

The lawsuit was originally filed against Republican legislative leaders in 2019 on behalf of several voting and civil rights groups including Community Success Initiative, Justice Served NC, the North Carolina NAACP, Wash Away Unemployment, and individuals convicted of felonies. "People who work, live, and pay taxes in our communities should not have their voices & votes silenced due to a previous felony conviction," tweeted Forward Justice, a Durham-based legal organization representing the plaintiffs.

The court found that the law was rooted in 19th-century white supremacy and had a disparate impact on Black people, who make up 20% of the state's voting age population but 40% of those who lost their voting rights for a felony conviction, according to 2018 data referenced in the lawsuit. The panel ruled that individuals who have completed their active prison time will be able to vote in the November elections. The decision could affect roughly 56,000 people, according to court testimony.

However, Republican state House Speaker Tim Moore and state Senate leader Phil Berger appealed the decision to the Republican-controlled North Carolina Court of Appeals. But last month, the Democratic-controlled state Supreme Court announced that it would take over the lawsuit per a request from the plaintiffs rather than wait for the Court of Appeals to rule. The move makes it more likely that the case will be resolved before the November general election.

A proposed amendment in Virginia

And in Virginia, Gov. Glenn Youngkin, a Republican, announced last month that he had restored voting rights to 3,496 individuals with felony convictions. "Individuals with their rights restored come from every walk of life and are eager to provide for themselves, their families and put the past behind them for a better tomorrow," Youngkin said. Though Virginia is among the states that permanently bar people with felony convictions from voting, the state constitution gives the governor the ability to restore voting rights to those who complete their criminal sentences. Both Republican and Democratic governors in Virginia have led rights restoration efforts for ex-felons in recent years.

Last year a constitutional amendment that would have automatically restored voting rights for felons upon completion of their incarceration. The bill passed the General Assembly last year, when Democrats led both the state House and Senate, but it was thwarted once Republicans took control of the House -- despite support across the political spectrum from groups including the American Conservative Union, Americans for Prosperity Virginia, the ACLU of Virginia, the Legal Aid Justice Center, the League of Women Voters of Virginia, the Virginia Interfaith Center for Public Policy, the Virginia Catholic Conference, and the Virginia NAACP.

Because Virginia law requires a proposed constitutional amendment to be passed by the General Assembly for two successive years before going to voters, the earliest a new version could possibly be implemented would be the fall of 2024. For now, former felons seeking to regain their voting rights will have to rely on Youngkin, who has yet to state his position on the proposed amendment.

In recent years, voting rights advocates and state lawmakers have made significant strides in restoring voting rights to U.S. citizens with felony convictions.

In the 2020 U.S. presidential election, 5.17 million people were disenfranchised due to a felony conviction, according to the Sentencing Project -- 15% fewer than in 2016, as states implemented measures to restore voting rights to people with felony convictions who served their sentences. From 2016 to 2020, at least 13 states expanded to some degree voting rights for ex-felons, including the Southern states of Alabama, Florida, Kentucky, Louisiana, and Virginia.

Historians point out that felony disenfranchisement laws are rooted in the Jim Crow era and were implemented to suppress Black electoral power. After Black men were granted the right to vote in 1870, Southern states started to adopt such laws, along with others designed to prevent Black voters from casting a ballot. According to a 2003 study from scholars at the University of Minnesota and Northwestern University, the greater a state's nonwhite prison population, the more likely it was to adopt stringent felony disenfranchisement laws. Currently, 11 states still permanently disenfranchise at least some individuals from voting due to past criminal convictions, including five in the South: Alabama, Florida, Kentucky, Mississippi, and Tennessee.

These laws continue to have a disproportionate impact on Black people and communities of color. For example, as of 2020 more than one in seven Black adults were disenfranchised in six of the 13 Southern states -- Alabama, Florida, Kentucky, Mississippi, Tennessee, and Virginia.

With the midterm elections now underway, efforts are continuing in several Southern states to restore voting rights to people with felony convictions who've completed their sentences. Those efforts could potentially have some impact on the outcome of the elections: A 2019 study found that laws re-enfranchising ex-felons had a "positive, but not statistically significant, effect" on the vote share of Democratic candidates and turnout rates of minority voters in U.S. House elections.

Voting rights activists had pressed Congress to pass federal legislation to restore the franchise to ex-felons nationwide. But in January, the Democrats' far-reaching pro-democracy bill failed to garner enough votes to overcome threats of a Republican filibuster. The measure would have established one national standard for restoring rights by mandating that a person's right to vote could not be "denied or abridged because that individual has been convicted of a criminal offense unless such individual is serving a felony sentence in a correctional institution or facility at the time of the election." As a consequence, the movement to restore ex-felons' voting rights is now focusing on the states.

A court challenge in Mississippi

Earlier this year in Mississippi, the legislature passed Senate Bill 2536, a Republican-sponsored proposal that would have made it easier for individuals with felony convictions to regain their voting rights after completing their sentences. However, Gov. Tate Reeves (R) vetoed it. Mississippi remains among the fewer than 10 states nationwide that do not automatically restore voting rights to people convicted of felonies after they complete their sentence. The law derives from the state's constitutional convention of 1890 that sought to develop a plan to block Black people from voting. State officials adopted a provision that barred voting by people convicted of specific felonies -- and the crimes they chose to include were those they thought Black people were more likely to commit. There are currently 23 specific crimes that result in a lifelong voting ban in the state.

Under current Mississippi law, voting rights can be restored only by a gubernatorial pardon or legislation that passes both the state House and Senate by a two-thirds vote. Mississippi is the only state in the nation that typically requires legislative action to restore ex-felons' voting rights. During the 2022 state legislative session, lawmakers took action to restore voting rights to just five people, while only 185 Mississippians convicted of felonies have had their voting rights restored by the legislature since 1997, The Guardian reports. And 2018 data shows that while Black people account for just 36% of the state's population they make up 61% of Mississippians who have lost their right to vote due to a felony conviction.

The Mississippi Constitution's felony disenfranchisement provision is currently being challenged in federal court for its racist intent by a 2017 lawsuit filed by the Mississippi Center for Justice on behalf of Roy Harness and Kamal Karriem. Last year a three-judge panel of the conservative 5th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals rejected efforts to continue the lawsuit, but then last June the court agreed to rehear the case, and there were oral arguments in September. A ruling is expected in the coming months. The decision will determine the constitutionality of the disenfranchisement provisions and the fate of former felons waiting to regain their right to vote

"At a time when most states have repealed their disfranchisement laws, it is time to remove from Mississippi's constitution this backward provision that was enacted with such a vicious purpose," said Vangela M. Wade, president and CEO of Mississippi Center for Justice.

Another lawsuit in North Carolina

In North Carolina, the fight for ex-felon voting rights is also being waged in the courts. In March, a three-judge Superior Court panel struck down a 1973 law that prevented people from voting while serving active sentences -- including when they are on probation or parole.

The lawsuit was originally filed against Republican legislative leaders in 2019 on behalf of several voting and civil rights groups including Community Success Initiative, Justice Served NC, the North Carolina NAACP, Wash Away Unemployment, and individuals convicted of felonies. "People who work, live, and pay taxes in our communities should not have their voices & votes silenced due to a previous felony conviction," tweeted Forward Justice, a Durham-based legal organization representing the plaintiffs.

The court found that the law was rooted in 19th-century white supremacy and had a disparate impact on Black people, who make up 20% of the state's voting age population but 40% of those who lost their voting rights for a felony conviction, according to 2018 data referenced in the lawsuit. The panel ruled that individuals who have completed their active prison time will be able to vote in the November elections. The decision could affect roughly 56,000 people, according to court testimony.

However, Republican state House Speaker Tim Moore and state Senate leader Phil Berger appealed the decision to the Republican-controlled North Carolina Court of Appeals. But last month, the Democratic-controlled state Supreme Court announced that it would take over the lawsuit per a request from the plaintiffs rather than wait for the Court of Appeals to rule. The move makes it more likely that the case will be resolved before the November general election.

A proposed amendment in Virginia

And in Virginia, Gov. Glenn Youngkin, a Republican, announced last month that he had restored voting rights to 3,496 individuals with felony convictions. "Individuals with their rights restored come from every walk of life and are eager to provide for themselves, their families and put the past behind them for a better tomorrow," Youngkin said. Though Virginia is among the states that permanently bar people with felony convictions from voting, the state constitution gives the governor the ability to restore voting rights to those who complete their criminal sentences. Both Republican and Democratic governors in Virginia have led rights restoration efforts for ex-felons in recent years.

Last year a constitutional amendment that would have automatically restored voting rights for felons upon completion of their incarceration. The bill passed the General Assembly last year, when Democrats led both the state House and Senate, but it was thwarted once Republicans took control of the House -- despite support across the political spectrum from groups including the American Conservative Union, Americans for Prosperity Virginia, the ACLU of Virginia, the Legal Aid Justice Center, the League of Women Voters of Virginia, the Virginia Interfaith Center for Public Policy, the Virginia Catholic Conference, and the Virginia NAACP.

Because Virginia law requires a proposed constitutional amendment to be passed by the General Assembly for two successive years before going to voters, the earliest a new version could possibly be implemented would be the fall of 2024. For now, former felons seeking to regain their voting rights will have to rely on Youngkin, who has yet to state his position on the proposed amendment.