SUBSCRIBE TO OUR FREE NEWSLETTER

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

5

#000000

#FFFFFF

To donate by check, phone, or other method, see our More Ways to Give page.

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

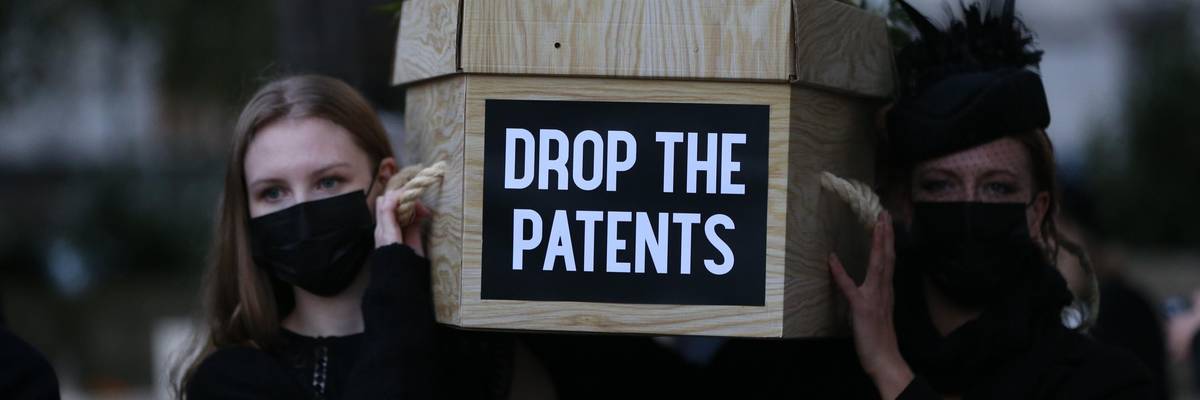

People carry mock coffins in front of British Prime Minister Boris Johnson's office in London on October 12, 2021. (Photo: Hasan Esen/Anadolu Agency via Getty Images)

The New York Times had an editorial about the corruption of the patent system in recent decades. It noted that the patent office is clearly not following the legal standards for issuing a patent, including that the item being patented is a genuine innovation and that it works. Among other things, it pointed out that Theranos had been issued dozens of patents for a technique that clearly did not work.

As the editorial notes, the worst patent abuses occur with prescription drugs. Drug companies routinely garner dozens of dubious patents for their leading sellers, making it extremely expensive for potential generic competitors to enter the market. The piece points out that the twelve drugs that get the most money from Medicare have an average of more than fifty patents each.

The piece suggests some useful reforms, but it misses the fundamental problem. When patents can be worth enormous sums of money, companies will find ways to abuse the system.

We need to understand the basic principle here. Patents are a government intervention in the free market, they impose a monopoly in a particular market.

We should think of patents like price controls under the Soviet system of central planning. This system routinely led to shortages in many areas. As a result, there was a huge black market. Well-positioned individuals pulled items like blue jeans or milk, or other consumer products out of the official system and sold them for a huge premium on the black market.

The Soviet Union responded by getting more police and imposing harsher penalties for black market trades, but the standard economist solution was to take the money away. By that we mean stop regulating prices, let the market determine the price. When that happens, there is no room for a black market.

We should think about patents in the same way. While patents can be a useful tool for promoting innovation, when huge sums are available by claiming a patent, we should expect there will be corruption, in spite of our best efforts to constrain it. This means that we should limit their use and try to ensure that we only rely on them where patent monopolies are clearly the best mechanism to promote innovation.

I have argued that we should rely on publicly funded research, rather than patent monopolies when it comes to prescription drugs and medical equipment. In addition to promoting corruption, these monopolies create the absurd situation where many lifesaving drugs that would sell in a free market for twenty or thirty dollars, instead sell for thousands or even tens of thousands of dollars. (Solvaldi, a breakthrough drug for treating Hepatitis C, sold here for $84,000 for a three-month course of treatment. A high-quality generic version was available in India for $300.)

The situation is made even worse by the fact that we typically have third party payers. This means that patients needing treatment have to persuade a government bureaucracy or private insurer to pay for an expensive drug that would cost just a few dollars in a free market.

The abuses are less severe in other areas, but we should be looking to reduce the value of patents (and copyrights) everywhere, and rely on alternative mechanisms for supporting innovation. I discuss alternatives in chapter 5 of Rigged (it's free).

It's great to see the New York Times recognize the abuses of the patent system. It would be even better if it opened its pages to discussion of alternative mechanisms for financing innovation.

Dear Common Dreams reader, The U.S. is on a fast track to authoritarianism like nothing I've ever seen. Meanwhile, corporate news outlets are utterly capitulating to Trump, twisting their coverage to avoid drawing his ire while lining up to stuff cash in his pockets. That's why I believe that Common Dreams is doing the best and most consequential reporting that we've ever done. Our small but mighty team is a progressive reporting powerhouse, covering the news every day that the corporate media never will. Our mission has always been simple: To inform. To inspire. And to ignite change for the common good. Now here's the key piece that I want all our readers to understand: None of this would be possible without your financial support. That's not just some fundraising cliche. It's the absolute and literal truth. We don't accept corporate advertising and never will. We don't have a paywall because we don't think people should be blocked from critical news based on their ability to pay. Everything we do is funded by the donations of readers like you. Will you donate now to help power the nonprofit, independent reporting of Common Dreams? Thank you for being a vital member of our community. Together, we can keep independent journalism alive when it’s needed most. - Craig Brown, Co-founder |

The New York Times had an editorial about the corruption of the patent system in recent decades. It noted that the patent office is clearly not following the legal standards for issuing a patent, including that the item being patented is a genuine innovation and that it works. Among other things, it pointed out that Theranos had been issued dozens of patents for a technique that clearly did not work.

As the editorial notes, the worst patent abuses occur with prescription drugs. Drug companies routinely garner dozens of dubious patents for their leading sellers, making it extremely expensive for potential generic competitors to enter the market. The piece points out that the twelve drugs that get the most money from Medicare have an average of more than fifty patents each.

The piece suggests some useful reforms, but it misses the fundamental problem. When patents can be worth enormous sums of money, companies will find ways to abuse the system.

We need to understand the basic principle here. Patents are a government intervention in the free market, they impose a monopoly in a particular market.

We should think of patents like price controls under the Soviet system of central planning. This system routinely led to shortages in many areas. As a result, there was a huge black market. Well-positioned individuals pulled items like blue jeans or milk, or other consumer products out of the official system and sold them for a huge premium on the black market.

The Soviet Union responded by getting more police and imposing harsher penalties for black market trades, but the standard economist solution was to take the money away. By that we mean stop regulating prices, let the market determine the price. When that happens, there is no room for a black market.

We should think about patents in the same way. While patents can be a useful tool for promoting innovation, when huge sums are available by claiming a patent, we should expect there will be corruption, in spite of our best efforts to constrain it. This means that we should limit their use and try to ensure that we only rely on them where patent monopolies are clearly the best mechanism to promote innovation.

I have argued that we should rely on publicly funded research, rather than patent monopolies when it comes to prescription drugs and medical equipment. In addition to promoting corruption, these monopolies create the absurd situation where many lifesaving drugs that would sell in a free market for twenty or thirty dollars, instead sell for thousands or even tens of thousands of dollars. (Solvaldi, a breakthrough drug for treating Hepatitis C, sold here for $84,000 for a three-month course of treatment. A high-quality generic version was available in India for $300.)

The situation is made even worse by the fact that we typically have third party payers. This means that patients needing treatment have to persuade a government bureaucracy or private insurer to pay for an expensive drug that would cost just a few dollars in a free market.

The abuses are less severe in other areas, but we should be looking to reduce the value of patents (and copyrights) everywhere, and rely on alternative mechanisms for supporting innovation. I discuss alternatives in chapter 5 of Rigged (it's free).

It's great to see the New York Times recognize the abuses of the patent system. It would be even better if it opened its pages to discussion of alternative mechanisms for financing innovation.

The New York Times had an editorial about the corruption of the patent system in recent decades. It noted that the patent office is clearly not following the legal standards for issuing a patent, including that the item being patented is a genuine innovation and that it works. Among other things, it pointed out that Theranos had been issued dozens of patents for a technique that clearly did not work.

As the editorial notes, the worst patent abuses occur with prescription drugs. Drug companies routinely garner dozens of dubious patents for their leading sellers, making it extremely expensive for potential generic competitors to enter the market. The piece points out that the twelve drugs that get the most money from Medicare have an average of more than fifty patents each.

The piece suggests some useful reforms, but it misses the fundamental problem. When patents can be worth enormous sums of money, companies will find ways to abuse the system.

We need to understand the basic principle here. Patents are a government intervention in the free market, they impose a monopoly in a particular market.

We should think of patents like price controls under the Soviet system of central planning. This system routinely led to shortages in many areas. As a result, there was a huge black market. Well-positioned individuals pulled items like blue jeans or milk, or other consumer products out of the official system and sold them for a huge premium on the black market.

The Soviet Union responded by getting more police and imposing harsher penalties for black market trades, but the standard economist solution was to take the money away. By that we mean stop regulating prices, let the market determine the price. When that happens, there is no room for a black market.

We should think about patents in the same way. While patents can be a useful tool for promoting innovation, when huge sums are available by claiming a patent, we should expect there will be corruption, in spite of our best efforts to constrain it. This means that we should limit their use and try to ensure that we only rely on them where patent monopolies are clearly the best mechanism to promote innovation.

I have argued that we should rely on publicly funded research, rather than patent monopolies when it comes to prescription drugs and medical equipment. In addition to promoting corruption, these monopolies create the absurd situation where many lifesaving drugs that would sell in a free market for twenty or thirty dollars, instead sell for thousands or even tens of thousands of dollars. (Solvaldi, a breakthrough drug for treating Hepatitis C, sold here for $84,000 for a three-month course of treatment. A high-quality generic version was available in India for $300.)

The situation is made even worse by the fact that we typically have third party payers. This means that patients needing treatment have to persuade a government bureaucracy or private insurer to pay for an expensive drug that would cost just a few dollars in a free market.

The abuses are less severe in other areas, but we should be looking to reduce the value of patents (and copyrights) everywhere, and rely on alternative mechanisms for supporting innovation. I discuss alternatives in chapter 5 of Rigged (it's free).

It's great to see the New York Times recognize the abuses of the patent system. It would be even better if it opened its pages to discussion of alternative mechanisms for financing innovation.