SUBSCRIBE TO OUR FREE NEWSLETTER

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

5

#000000

#FFFFFF

To donate by check, phone, or other method, see our More Ways to Give page.

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

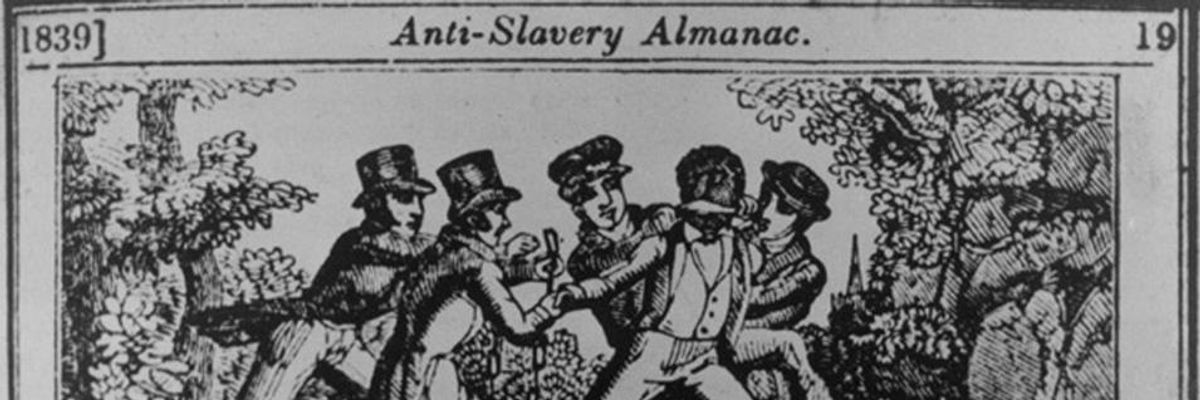

An 1839 woodcut depicts a slave patrol capturing a fugitive. (Anti-Slavery Almanac/Public domain)

For decades, we've been told that policing is a public good: available to all, for the benefit of all. But in practice, that's never been true.

One of the basic measures of a "public good" is that it's accessible to all people in a society, regardless of ability to pay. But from the beginning, policing in this country was designed to protect the assets of the most privileged.

Boston merchants were the first to persuade lawmakers in 1838 that a full-time, publicly funded police force would serve the "collective good." In reality, they wanted to get the public to pay for protecting their shipped goods and routes.

In the South, where the economy depended on enslaved labor, publicly funded slave patrols were created in 1704 to surveil, track, and punish Black people who attempted to escape. As historian Sally Hadden notes, "Most law enforcement was, by definition, white patrolmen watching, catching, or beating Black slaves" -- who were legally considered the property of wealthy white men.

Today, all across the United States, landlords and property managers enlist law enforcement to forcibly evict low-income tenants. Police regularly remove homeless individuals from parks and public spaces. And cops routinely stop, search, and threaten Black and brown people when they drive or walk through white neighborhoods.

We've seen these disparities in policing increase since the outbreak of COVID-19. And soon, with eviction moratoriums lifting across the country, tens of thousands of struggling tenants will be sent eviction notices. When families have no place else to go and landlords call in law enforcement, who do you think the police will serve and protect?

For centuries, police have taken the side of power, at the expense of those most marginalized.

Police have never protected Black lives as much as they protect white property. And when people protest having their safety threatened -- as in the nationwide protests after the murder of George Floyd -- they're met with further violence from police.

Safety is born out of investment in true public goods. Policing in America reveals a lack of it.

If people had guaranteed housing, there would be no one sleeping in subway cars, in parks, or on sidewalks for the police to round up. If people had universal health care, mental health problems might be treated instead of criminalized. And if we had a federal jobs guarantee, people would not be forced into an underground economy that fuels a cruel and punishing prison system.

But instead of addressing root causes of insecurity, leaders of both parties have often chosen to defund education and hospitals while resisting significant reductions to policing.

What if public safety were a public good? What would that look like?

It would mean funding nonviolent tools to de-escalate and respond to safety concerns. It would mean engaging community members in collective decision-making, since each community has unique needs. And, most importantly, it means using an anti-racist framework to create new approaches to public safety.

We're in a transformative moment in history where structural change is within our grasp. Reform has failed time and time again to address the problem of police violence. It's more clear than ever that we need to divest from policing and invest in universal public goods that create true public safety, not just the illusion of it.

Dear Common Dreams reader, The U.S. is on a fast track to authoritarianism like nothing I've ever seen. Meanwhile, corporate news outlets are utterly capitulating to Trump, twisting their coverage to avoid drawing his ire while lining up to stuff cash in his pockets. That's why I believe that Common Dreams is doing the best and most consequential reporting that we've ever done. Our small but mighty team is a progressive reporting powerhouse, covering the news every day that the corporate media never will. Our mission has always been simple: To inform. To inspire. And to ignite change for the common good. Now here's the key piece that I want all our readers to understand: None of this would be possible without your financial support. That's not just some fundraising cliche. It's the absolute and literal truth. We don't accept corporate advertising and never will. We don't have a paywall because we don't think people should be blocked from critical news based on their ability to pay. Everything we do is funded by the donations of readers like you. Will you donate now to help power the nonprofit, independent reporting of Common Dreams? Thank you for being a vital member of our community. Together, we can keep independent journalism alive when it’s needed most. - Craig Brown, Co-founder |

For decades, we've been told that policing is a public good: available to all, for the benefit of all. But in practice, that's never been true.

One of the basic measures of a "public good" is that it's accessible to all people in a society, regardless of ability to pay. But from the beginning, policing in this country was designed to protect the assets of the most privileged.

Boston merchants were the first to persuade lawmakers in 1838 that a full-time, publicly funded police force would serve the "collective good." In reality, they wanted to get the public to pay for protecting their shipped goods and routes.

In the South, where the economy depended on enslaved labor, publicly funded slave patrols were created in 1704 to surveil, track, and punish Black people who attempted to escape. As historian Sally Hadden notes, "Most law enforcement was, by definition, white patrolmen watching, catching, or beating Black slaves" -- who were legally considered the property of wealthy white men.

Today, all across the United States, landlords and property managers enlist law enforcement to forcibly evict low-income tenants. Police regularly remove homeless individuals from parks and public spaces. And cops routinely stop, search, and threaten Black and brown people when they drive or walk through white neighborhoods.

We've seen these disparities in policing increase since the outbreak of COVID-19. And soon, with eviction moratoriums lifting across the country, tens of thousands of struggling tenants will be sent eviction notices. When families have no place else to go and landlords call in law enforcement, who do you think the police will serve and protect?

For centuries, police have taken the side of power, at the expense of those most marginalized.

Police have never protected Black lives as much as they protect white property. And when people protest having their safety threatened -- as in the nationwide protests after the murder of George Floyd -- they're met with further violence from police.

Safety is born out of investment in true public goods. Policing in America reveals a lack of it.

If people had guaranteed housing, there would be no one sleeping in subway cars, in parks, or on sidewalks for the police to round up. If people had universal health care, mental health problems might be treated instead of criminalized. And if we had a federal jobs guarantee, people would not be forced into an underground economy that fuels a cruel and punishing prison system.

But instead of addressing root causes of insecurity, leaders of both parties have often chosen to defund education and hospitals while resisting significant reductions to policing.

What if public safety were a public good? What would that look like?

It would mean funding nonviolent tools to de-escalate and respond to safety concerns. It would mean engaging community members in collective decision-making, since each community has unique needs. And, most importantly, it means using an anti-racist framework to create new approaches to public safety.

We're in a transformative moment in history where structural change is within our grasp. Reform has failed time and time again to address the problem of police violence. It's more clear than ever that we need to divest from policing and invest in universal public goods that create true public safety, not just the illusion of it.

For decades, we've been told that policing is a public good: available to all, for the benefit of all. But in practice, that's never been true.

One of the basic measures of a "public good" is that it's accessible to all people in a society, regardless of ability to pay. But from the beginning, policing in this country was designed to protect the assets of the most privileged.

Boston merchants were the first to persuade lawmakers in 1838 that a full-time, publicly funded police force would serve the "collective good." In reality, they wanted to get the public to pay for protecting their shipped goods and routes.

In the South, where the economy depended on enslaved labor, publicly funded slave patrols were created in 1704 to surveil, track, and punish Black people who attempted to escape. As historian Sally Hadden notes, "Most law enforcement was, by definition, white patrolmen watching, catching, or beating Black slaves" -- who were legally considered the property of wealthy white men.

Today, all across the United States, landlords and property managers enlist law enforcement to forcibly evict low-income tenants. Police regularly remove homeless individuals from parks and public spaces. And cops routinely stop, search, and threaten Black and brown people when they drive or walk through white neighborhoods.

We've seen these disparities in policing increase since the outbreak of COVID-19. And soon, with eviction moratoriums lifting across the country, tens of thousands of struggling tenants will be sent eviction notices. When families have no place else to go and landlords call in law enforcement, who do you think the police will serve and protect?

For centuries, police have taken the side of power, at the expense of those most marginalized.

Police have never protected Black lives as much as they protect white property. And when people protest having their safety threatened -- as in the nationwide protests after the murder of George Floyd -- they're met with further violence from police.

Safety is born out of investment in true public goods. Policing in America reveals a lack of it.

If people had guaranteed housing, there would be no one sleeping in subway cars, in parks, or on sidewalks for the police to round up. If people had universal health care, mental health problems might be treated instead of criminalized. And if we had a federal jobs guarantee, people would not be forced into an underground economy that fuels a cruel and punishing prison system.

But instead of addressing root causes of insecurity, leaders of both parties have often chosen to defund education and hospitals while resisting significant reductions to policing.

What if public safety were a public good? What would that look like?

It would mean funding nonviolent tools to de-escalate and respond to safety concerns. It would mean engaging community members in collective decision-making, since each community has unique needs. And, most importantly, it means using an anti-racist framework to create new approaches to public safety.

We're in a transformative moment in history where structural change is within our grasp. Reform has failed time and time again to address the problem of police violence. It's more clear than ever that we need to divest from policing and invest in universal public goods that create true public safety, not just the illusion of it.