The upcoming Super Tuesday primaries will include two states -- Colorado and Utah -- that have shifted completely to vote at home systems, as well as California, which has allowed counties to run all-mail elections for years and is transitioning into a fully vote at home system in the next few years. (Photo: Getty Images)

To Reduce Inequality in the Election Process, All States Should Allow Voting At Home

Letting people fill out ballots at their kitchen table and pop them in the mail reduces economic barriers to participation for low-income Americans.

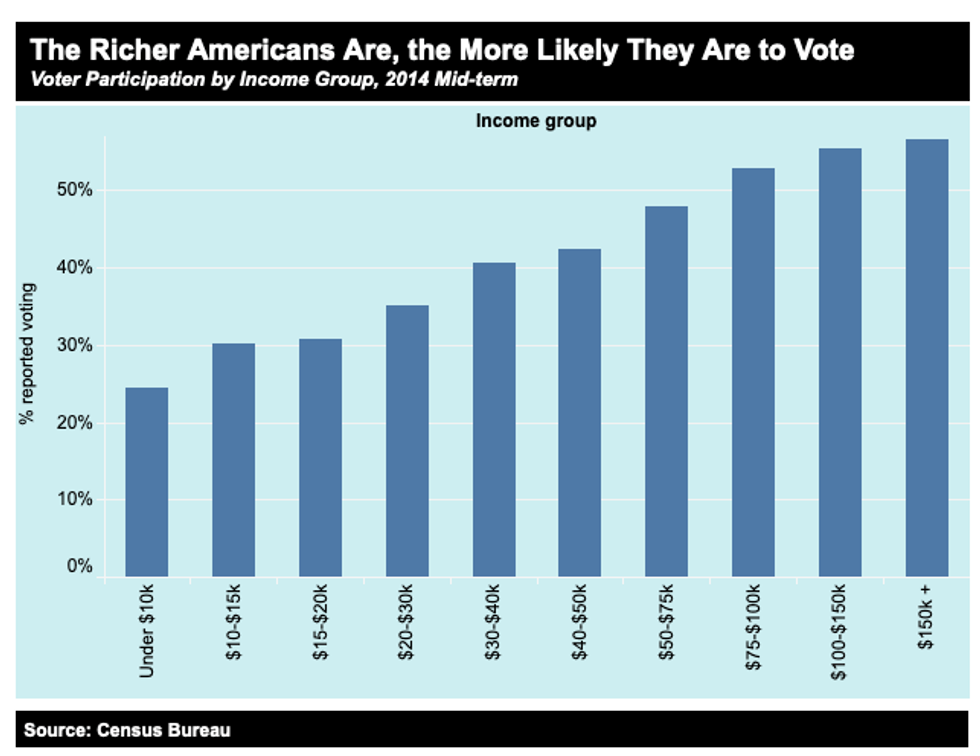

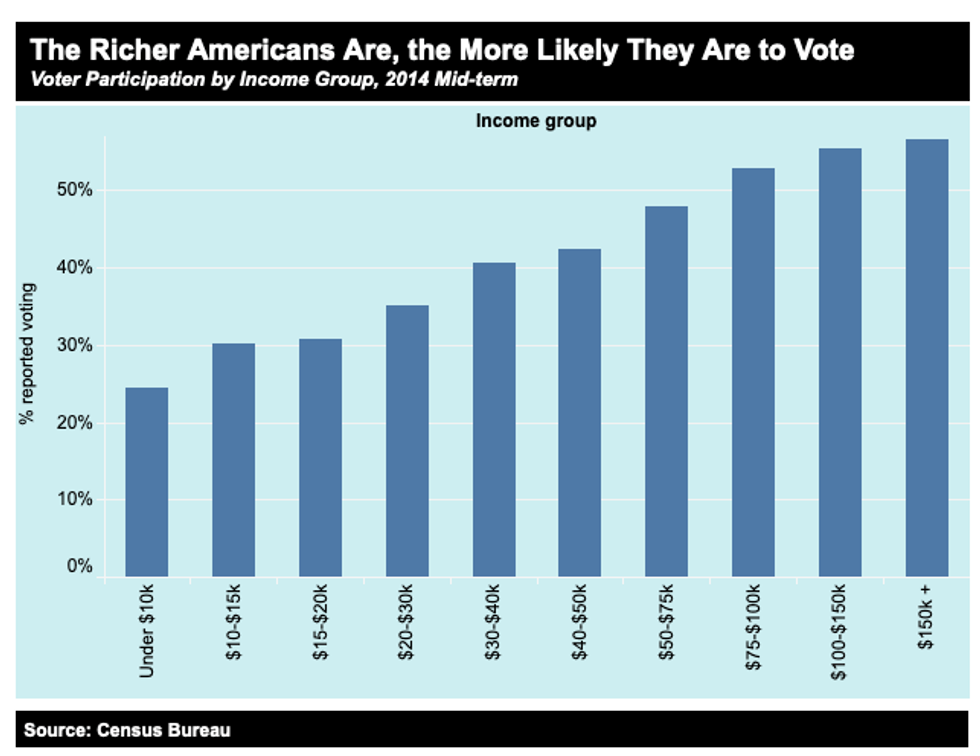

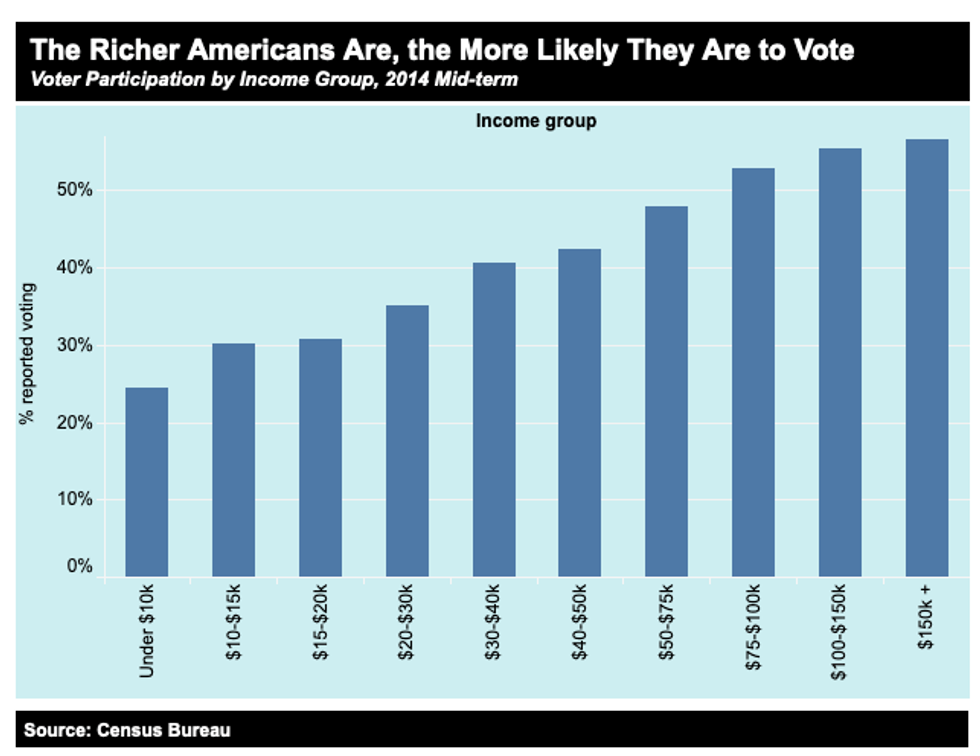

In the United States of America, we have an election process in which the wealthiest Americans can spend unlimited funds to buy political influence while the poor, particularly poor people of color, face multiple barriers to exercising their most basic democratic right: voting.

As a result, the richer the American, the likelier they are to vote. According to the most recent Census data, voters with household income of more than $150,000 had a 56.6 percent participation rate in the 2014 mid-terms, compared to just 31 percent for those making $15,000 to $20,000.

A major reason for this disparity: lower-income Americans have a harder time getting to the polls. They might not be able to afford to take time off work, pay for childcare, or cover the transportation costs.

One solution to these types of barriers is "vote at home." Also commonly referred to as "vote by mail," this pro-democracy reform allows people to receive their ballots through the mail weeks before an election, fill them out at their convenience, and return them either in-person or by mail.

The upcoming Super Tuesday primaries will include two states -- Colorado and Utah -- that have shifted completely to vote at home systems, as well as California, which has allowed counties to run all-mail elections for years and is transitioning into a fully vote at home system in the next few years.

Three additional states -- Oregon, Washington, Hawaii -- will have statewide vote at home elections this year. Many others have moved in this direction by allowing "no excuse" absentee voting.

If all states adopted the vote at home system, it would significantly reduce the economic disparities in our voting system. Senator Ron Wyden of Oregon has proposed such a bill in Congress.

Research indicates that vote at home localities have higher turnout rates. Rockville, Maryland is a prime example. When the city held a municipal election by mail in 2019, turnout almost doubled over the previous mayoral election.

Given the Census data on income and voting rates, one can assume that increased turnout means higher participation of low-income Americans. A study in Utah provides even more clear evidence. The study showed that in the 2016 general election, when the state had only a partial vote at home system, registered voters in counties that had adopted vote at home and had household income of less than $30,000 had a 79.1 percent participation rate. That was significantly higher than the 74.6 percent participation rate for Utah voters in that income group who lived in counties without this voting option.

Voting at home also benefits disabled people, seniors, and rural voters -- all groups that are disproportionately likely to be low-income. Many voting precincts are inaccessible for the disabled, according to a 2013 GAO report. Rural voters may have to deal with long drives to their polling places. The Census found that 33.9 percent of those 65 years and older who did not vote in 2016 cited illness or disability as the reason.

Concerns about fraud in vote at home processes have been widely debunked.

Two labor unions representing postal workers -- the American Postal Workers Union and the National Association of Letter Carriers -- vocally support vote at home reforms. That is in part because they generate some revenue for the U.S. Postal Service, but also because they help counter the disturbing rise of racist voter suppression laws, like voter ID requirements, in many states across the country.

"We are in an era of new 'Jim Crow' laws intended to suppress the voting rights of minorities, the poor, the disenfranchised, the working and the elderly," said APWU President Mark Dimondstein at a press conference in the lead-up to the last presidential election. "Without convenient and fair access to the ballot box, the right to vote is indeed a right diminished."

In congressional testimony on February 26, Bishop Dr. William J. Barber II, co-chair of the Poor People's Campaign, identified several other critical steps policymakers must take to strengthen our democracy and ensure equal protection under the law, including full restoration and expansion of the Voting Rights Act, an end to racist gerrymandering and redistricting, and the right to vote for the currently and formerly incarcerated.

Making it easier for all Americans to vote is not just about strengthening our democracy. It could also help narrow our economic divide. A Cambridge University study found that when there is less "class bias" in voter participation (i.e., the process does not favor the wealthy), it actually leads to lower income inequality in a society.

This shouldn't be much of a surprise. When low-income citizens aren't able to exercise their right to vote, they have less power to push candidates to commit to fighting poverty and inequality.

A nationwide vote at home policy wouldn't fix all the flaws in our election system. But it should be a vital part of a broader agenda to level the democratic playing field for less privileged Americans.

An Urgent Message From Our Co-Founder

Dear Common Dreams reader, The U.S. is on a fast track to authoritarianism like nothing I've ever seen. Meanwhile, corporate news outlets are utterly capitulating to Trump, twisting their coverage to avoid drawing his ire while lining up to stuff cash in his pockets. That's why I believe that Common Dreams is doing the best and most consequential reporting that we've ever done. Our small but mighty team is a progressive reporting powerhouse, covering the news every day that the corporate media never will. Our mission has always been simple: To inform. To inspire. And to ignite change for the common good. Now here's the key piece that I want all our readers to understand: None of this would be possible without your financial support. That's not just some fundraising cliche. It's the absolute and literal truth. We don't accept corporate advertising and never will. We don't have a paywall because we don't think people should be blocked from critical news based on their ability to pay. Everything we do is funded by the donations of readers like you. Will you donate now to help power the nonprofit, independent reporting of Common Dreams? Thank you for being a vital member of our community. Together, we can keep independent journalism alive when it’s needed most. - Craig Brown, Co-founder |

In the United States of America, we have an election process in which the wealthiest Americans can spend unlimited funds to buy political influence while the poor, particularly poor people of color, face multiple barriers to exercising their most basic democratic right: voting.

As a result, the richer the American, the likelier they are to vote. According to the most recent Census data, voters with household income of more than $150,000 had a 56.6 percent participation rate in the 2014 mid-terms, compared to just 31 percent for those making $15,000 to $20,000.

A major reason for this disparity: lower-income Americans have a harder time getting to the polls. They might not be able to afford to take time off work, pay for childcare, or cover the transportation costs.

One solution to these types of barriers is "vote at home." Also commonly referred to as "vote by mail," this pro-democracy reform allows people to receive their ballots through the mail weeks before an election, fill them out at their convenience, and return them either in-person or by mail.

The upcoming Super Tuesday primaries will include two states -- Colorado and Utah -- that have shifted completely to vote at home systems, as well as California, which has allowed counties to run all-mail elections for years and is transitioning into a fully vote at home system in the next few years.

Three additional states -- Oregon, Washington, Hawaii -- will have statewide vote at home elections this year. Many others have moved in this direction by allowing "no excuse" absentee voting.

If all states adopted the vote at home system, it would significantly reduce the economic disparities in our voting system. Senator Ron Wyden of Oregon has proposed such a bill in Congress.

Research indicates that vote at home localities have higher turnout rates. Rockville, Maryland is a prime example. When the city held a municipal election by mail in 2019, turnout almost doubled over the previous mayoral election.

Given the Census data on income and voting rates, one can assume that increased turnout means higher participation of low-income Americans. A study in Utah provides even more clear evidence. The study showed that in the 2016 general election, when the state had only a partial vote at home system, registered voters in counties that had adopted vote at home and had household income of less than $30,000 had a 79.1 percent participation rate. That was significantly higher than the 74.6 percent participation rate for Utah voters in that income group who lived in counties without this voting option.

Voting at home also benefits disabled people, seniors, and rural voters -- all groups that are disproportionately likely to be low-income. Many voting precincts are inaccessible for the disabled, according to a 2013 GAO report. Rural voters may have to deal with long drives to their polling places. The Census found that 33.9 percent of those 65 years and older who did not vote in 2016 cited illness or disability as the reason.

Concerns about fraud in vote at home processes have been widely debunked.

Two labor unions representing postal workers -- the American Postal Workers Union and the National Association of Letter Carriers -- vocally support vote at home reforms. That is in part because they generate some revenue for the U.S. Postal Service, but also because they help counter the disturbing rise of racist voter suppression laws, like voter ID requirements, in many states across the country.

"We are in an era of new 'Jim Crow' laws intended to suppress the voting rights of minorities, the poor, the disenfranchised, the working and the elderly," said APWU President Mark Dimondstein at a press conference in the lead-up to the last presidential election. "Without convenient and fair access to the ballot box, the right to vote is indeed a right diminished."

In congressional testimony on February 26, Bishop Dr. William J. Barber II, co-chair of the Poor People's Campaign, identified several other critical steps policymakers must take to strengthen our democracy and ensure equal protection under the law, including full restoration and expansion of the Voting Rights Act, an end to racist gerrymandering and redistricting, and the right to vote for the currently and formerly incarcerated.

Making it easier for all Americans to vote is not just about strengthening our democracy. It could also help narrow our economic divide. A Cambridge University study found that when there is less "class bias" in voter participation (i.e., the process does not favor the wealthy), it actually leads to lower income inequality in a society.

This shouldn't be much of a surprise. When low-income citizens aren't able to exercise their right to vote, they have less power to push candidates to commit to fighting poverty and inequality.

A nationwide vote at home policy wouldn't fix all the flaws in our election system. But it should be a vital part of a broader agenda to level the democratic playing field for less privileged Americans.

In the United States of America, we have an election process in which the wealthiest Americans can spend unlimited funds to buy political influence while the poor, particularly poor people of color, face multiple barriers to exercising their most basic democratic right: voting.

As a result, the richer the American, the likelier they are to vote. According to the most recent Census data, voters with household income of more than $150,000 had a 56.6 percent participation rate in the 2014 mid-terms, compared to just 31 percent for those making $15,000 to $20,000.

A major reason for this disparity: lower-income Americans have a harder time getting to the polls. They might not be able to afford to take time off work, pay for childcare, or cover the transportation costs.

One solution to these types of barriers is "vote at home." Also commonly referred to as "vote by mail," this pro-democracy reform allows people to receive their ballots through the mail weeks before an election, fill them out at their convenience, and return them either in-person or by mail.

The upcoming Super Tuesday primaries will include two states -- Colorado and Utah -- that have shifted completely to vote at home systems, as well as California, which has allowed counties to run all-mail elections for years and is transitioning into a fully vote at home system in the next few years.

Three additional states -- Oregon, Washington, Hawaii -- will have statewide vote at home elections this year. Many others have moved in this direction by allowing "no excuse" absentee voting.

If all states adopted the vote at home system, it would significantly reduce the economic disparities in our voting system. Senator Ron Wyden of Oregon has proposed such a bill in Congress.

Research indicates that vote at home localities have higher turnout rates. Rockville, Maryland is a prime example. When the city held a municipal election by mail in 2019, turnout almost doubled over the previous mayoral election.

Given the Census data on income and voting rates, one can assume that increased turnout means higher participation of low-income Americans. A study in Utah provides even more clear evidence. The study showed that in the 2016 general election, when the state had only a partial vote at home system, registered voters in counties that had adopted vote at home and had household income of less than $30,000 had a 79.1 percent participation rate. That was significantly higher than the 74.6 percent participation rate for Utah voters in that income group who lived in counties without this voting option.

Voting at home also benefits disabled people, seniors, and rural voters -- all groups that are disproportionately likely to be low-income. Many voting precincts are inaccessible for the disabled, according to a 2013 GAO report. Rural voters may have to deal with long drives to their polling places. The Census found that 33.9 percent of those 65 years and older who did not vote in 2016 cited illness or disability as the reason.

Concerns about fraud in vote at home processes have been widely debunked.

Two labor unions representing postal workers -- the American Postal Workers Union and the National Association of Letter Carriers -- vocally support vote at home reforms. That is in part because they generate some revenue for the U.S. Postal Service, but also because they help counter the disturbing rise of racist voter suppression laws, like voter ID requirements, in many states across the country.

"We are in an era of new 'Jim Crow' laws intended to suppress the voting rights of minorities, the poor, the disenfranchised, the working and the elderly," said APWU President Mark Dimondstein at a press conference in the lead-up to the last presidential election. "Without convenient and fair access to the ballot box, the right to vote is indeed a right diminished."

In congressional testimony on February 26, Bishop Dr. William J. Barber II, co-chair of the Poor People's Campaign, identified several other critical steps policymakers must take to strengthen our democracy and ensure equal protection under the law, including full restoration and expansion of the Voting Rights Act, an end to racist gerrymandering and redistricting, and the right to vote for the currently and formerly incarcerated.

Making it easier for all Americans to vote is not just about strengthening our democracy. It could also help narrow our economic divide. A Cambridge University study found that when there is less "class bias" in voter participation (i.e., the process does not favor the wealthy), it actually leads to lower income inequality in a society.

This shouldn't be much of a surprise. When low-income citizens aren't able to exercise their right to vote, they have less power to push candidates to commit to fighting poverty and inequality.

A nationwide vote at home policy wouldn't fix all the flaws in our election system. But it should be a vital part of a broader agenda to level the democratic playing field for less privileged Americans.