SUBSCRIBE TO OUR FREE NEWSLETTER

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

5

#000000

#FFFFFF

To donate by check, phone, or other method, see our More Ways to Give page.

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

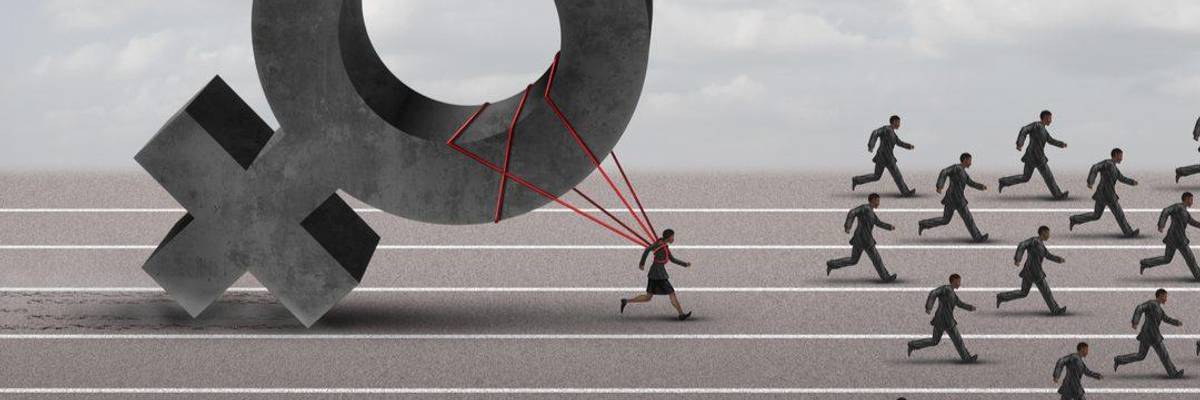

Womanhood becomes a real drag when I'm in roles I am qualified for and my expertise is questioned in ways it would not be if I were a man. (Photo: Shutterstock)

Was that sexist? Did he treat me that way because I'm a woman? Or would everything that just happened be exactly the same if I were a man?

Those are familiar questions for women. For as many times when you can know for sure you've experienced sexism, there are so many more times when you can't be sure -- but you wonder.

For me right now, most of the questions are coming from my new job. I'm in grad school for sociology, but I'm an avid hiker and backpacker when I'm not studying. I decided to take a part time job at an outdoor gear retailer.

I am a woman, I am short, and I look a decade younger than my age.

I'm used to all of the usual nonsense solo women backpackers get: people think we aren't safe in the woods alone, or well-meaning men assume we can't lift our own backpacks and offer to help, or they ask if we're just like Cheryl Strayed, the woman who wrote about her 1,000 mile solo hike on the Pacific Crest Trail in her bestselling book Wild.

As a sociologist, I know that people interpret my behavior in relation to their expectations of a woman's gender role.

Mostly it's not offensive. It just gets old.

Now that I'm in a position to advise all levels of hikers, from novice to expert, on their gear, I suspect my gender plays into my interactions in another way. I can't prove it, but I suspect that the advice I give would be trusted more if I were a man.

As a sociologist, I know that people interpret my behavior in relation to their expectations of a woman's gender role. I'm expected to be nurturing. If I step out of line, I become "shrill" or "bossy."

Womanhood becomes a real drag when I'm in roles I am qualified for and my expertise is questioned in ways it would not be if I were a man.

Masculinities scholar R.W. Connell found that middle class men express their masculinity through expertise and knowledge.

It's not true that nobody will ever see a woman as an expert. Nor is it true that all men are seen as experts. It simply means that because expertise is seen as a "masculine" trait, we find it easier to believe a man is an expert than a woman is one.

And when we do this, we don't see ourselves as sexist. Although our impressions of other are colored by the biases we all hold about race, class, gender, age, sexual orientation, disability, and so on, they feel so natural that we don't think we are biased at all. When people are biased but unaware of their biases, it makes it very difficult to discuss or change those biases.

When I advise a customer that the gear they're buying is unsuitable for the hike they're planning, or that the hike they are planning will be unpleasant at best and dangerous at worst, they often don't believe me.

Do I just look like a silly little girl who couldn't possibly provide expert advice about backpacking? Or would they equally blow off a man giving the same advice? I'll never know.

Being a woman doesn't just mean experiencing clear cut, obvious instances of sexism. It also means constantly wondering if you would have been treated with more respect if you were a man, then wondering what the heck to do about it -- and most of the time, doing nothing at all.

Dear Common Dreams reader, The U.S. is on a fast track to authoritarianism like nothing I've ever seen. Meanwhile, corporate news outlets are utterly capitulating to Trump, twisting their coverage to avoid drawing his ire while lining up to stuff cash in his pockets. That's why I believe that Common Dreams is doing the best and most consequential reporting that we've ever done. Our small but mighty team is a progressive reporting powerhouse, covering the news every day that the corporate media never will. Our mission has always been simple: To inform. To inspire. And to ignite change for the common good. Now here's the key piece that I want all our readers to understand: None of this would be possible without your financial support. That's not just some fundraising cliche. It's the absolute and literal truth. We don't accept corporate advertising and never will. We don't have a paywall because we don't think people should be blocked from critical news based on their ability to pay. Everything we do is funded by the donations of readers like you. Will you donate now to help power the nonprofit, independent reporting of Common Dreams? Thank you for being a vital member of our community. Together, we can keep independent journalism alive when it’s needed most. - Craig Brown, Co-founder |

Was that sexist? Did he treat me that way because I'm a woman? Or would everything that just happened be exactly the same if I were a man?

Those are familiar questions for women. For as many times when you can know for sure you've experienced sexism, there are so many more times when you can't be sure -- but you wonder.

For me right now, most of the questions are coming from my new job. I'm in grad school for sociology, but I'm an avid hiker and backpacker when I'm not studying. I decided to take a part time job at an outdoor gear retailer.

I am a woman, I am short, and I look a decade younger than my age.

I'm used to all of the usual nonsense solo women backpackers get: people think we aren't safe in the woods alone, or well-meaning men assume we can't lift our own backpacks and offer to help, or they ask if we're just like Cheryl Strayed, the woman who wrote about her 1,000 mile solo hike on the Pacific Crest Trail in her bestselling book Wild.

As a sociologist, I know that people interpret my behavior in relation to their expectations of a woman's gender role.

Mostly it's not offensive. It just gets old.

Now that I'm in a position to advise all levels of hikers, from novice to expert, on their gear, I suspect my gender plays into my interactions in another way. I can't prove it, but I suspect that the advice I give would be trusted more if I were a man.

As a sociologist, I know that people interpret my behavior in relation to their expectations of a woman's gender role. I'm expected to be nurturing. If I step out of line, I become "shrill" or "bossy."

Womanhood becomes a real drag when I'm in roles I am qualified for and my expertise is questioned in ways it would not be if I were a man.

Masculinities scholar R.W. Connell found that middle class men express their masculinity through expertise and knowledge.

It's not true that nobody will ever see a woman as an expert. Nor is it true that all men are seen as experts. It simply means that because expertise is seen as a "masculine" trait, we find it easier to believe a man is an expert than a woman is one.

And when we do this, we don't see ourselves as sexist. Although our impressions of other are colored by the biases we all hold about race, class, gender, age, sexual orientation, disability, and so on, they feel so natural that we don't think we are biased at all. When people are biased but unaware of their biases, it makes it very difficult to discuss or change those biases.

When I advise a customer that the gear they're buying is unsuitable for the hike they're planning, or that the hike they are planning will be unpleasant at best and dangerous at worst, they often don't believe me.

Do I just look like a silly little girl who couldn't possibly provide expert advice about backpacking? Or would they equally blow off a man giving the same advice? I'll never know.

Being a woman doesn't just mean experiencing clear cut, obvious instances of sexism. It also means constantly wondering if you would have been treated with more respect if you were a man, then wondering what the heck to do about it -- and most of the time, doing nothing at all.

Was that sexist? Did he treat me that way because I'm a woman? Or would everything that just happened be exactly the same if I were a man?

Those are familiar questions for women. For as many times when you can know for sure you've experienced sexism, there are so many more times when you can't be sure -- but you wonder.

For me right now, most of the questions are coming from my new job. I'm in grad school for sociology, but I'm an avid hiker and backpacker when I'm not studying. I decided to take a part time job at an outdoor gear retailer.

I am a woman, I am short, and I look a decade younger than my age.

I'm used to all of the usual nonsense solo women backpackers get: people think we aren't safe in the woods alone, or well-meaning men assume we can't lift our own backpacks and offer to help, or they ask if we're just like Cheryl Strayed, the woman who wrote about her 1,000 mile solo hike on the Pacific Crest Trail in her bestselling book Wild.

As a sociologist, I know that people interpret my behavior in relation to their expectations of a woman's gender role.

Mostly it's not offensive. It just gets old.

Now that I'm in a position to advise all levels of hikers, from novice to expert, on their gear, I suspect my gender plays into my interactions in another way. I can't prove it, but I suspect that the advice I give would be trusted more if I were a man.

As a sociologist, I know that people interpret my behavior in relation to their expectations of a woman's gender role. I'm expected to be nurturing. If I step out of line, I become "shrill" or "bossy."

Womanhood becomes a real drag when I'm in roles I am qualified for and my expertise is questioned in ways it would not be if I were a man.

Masculinities scholar R.W. Connell found that middle class men express their masculinity through expertise and knowledge.

It's not true that nobody will ever see a woman as an expert. Nor is it true that all men are seen as experts. It simply means that because expertise is seen as a "masculine" trait, we find it easier to believe a man is an expert than a woman is one.

And when we do this, we don't see ourselves as sexist. Although our impressions of other are colored by the biases we all hold about race, class, gender, age, sexual orientation, disability, and so on, they feel so natural that we don't think we are biased at all. When people are biased but unaware of their biases, it makes it very difficult to discuss or change those biases.

When I advise a customer that the gear they're buying is unsuitable for the hike they're planning, or that the hike they are planning will be unpleasant at best and dangerous at worst, they often don't believe me.

Do I just look like a silly little girl who couldn't possibly provide expert advice about backpacking? Or would they equally blow off a man giving the same advice? I'll never know.

Being a woman doesn't just mean experiencing clear cut, obvious instances of sexism. It also means constantly wondering if you would have been treated with more respect if you were a man, then wondering what the heck to do about it -- and most of the time, doing nothing at all.