SUBSCRIBE TO OUR FREE NEWSLETTER

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

5

#000000

#FFFFFF

To donate by check, phone, or other method, see our More Ways to Give page.

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

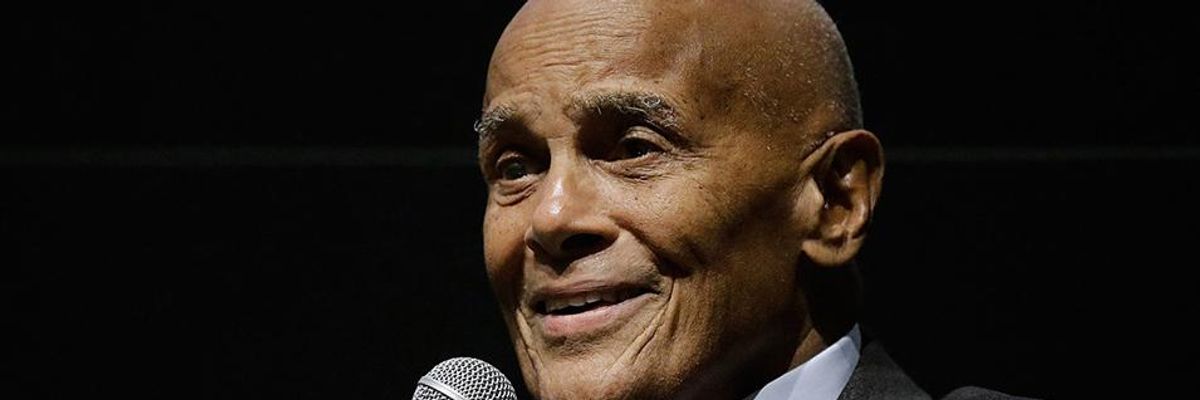

Harry Belafonte

Activist and artist Harry Belafonte could be sitting or standing when you meet him, but he's usually the only true giant in the room. Meeting Mr. Belafonte and his wife, Pamela, in the green room of the Carnegie Music Hall last Friday was a perk resulting from having interviewed him by phone the week before.

Mr. Belafonte was in Pittsburgh ostensibly to give a speech about the state of civil rights and black politics. The truth is that he could've come to town to read from the phone book and still attracted the 1,000 people who turned up for what he would call on stage later that night his "last public appearance."

When he extended his hand in the green room, I was struck by the fact that it was the same hand that had gripped Paul Robeson's and Eleanor Roosevelt's in gratitude for their mentorship in the 1940s. It was the same hand that clasped Martin Luther King's in friendship in the early 1950s, years before he was the civil rights leader he would eventually become.

When you shake hands with Mr. Belafonte, you're one degree of separation from Charlie Parker, Miles Davis and Lester Young at the Royal Roost giving advice to an earnest young singer who had until recently been a janitor's assistant in Harlem.

When Harry Belafonte smiles at you, you wonder if the magnetism radiating from him in torrents is something his fellow thespians Marlon Brando, Tony Curtis, Bea Arthur and Sidney Poitier recognized when they all took acting workshops together in Greenwich Village in the postwar years.

If you can avoid a sense of giddiness having your hand clasped by a man who shook hands with Woody Guthrie and Leadbelly after catching them in concert at the Village Vanguard, then you're blessed with a less imposing sense of history than I am.

After all, this was the same hand that James Baldwin shook. It was these fingers that caressed Dorothy Dandridge's cheeks in "Carmen Jones." It belongs to the man who gave Bob Dylan his first professional recording gig. Coretta Scott King cried on this man's shoulders after her husband was assassinated. Decades later, Nelson Mandela would embrace him in revolutionary solidarity for producing music that helped keep him alive. I was shaking hands with a man who constantly stood at the apex of American history.

I don't often find myself at a loss for words around famous people, but somehow I kept my prattling to a minimum while he regaled the four of us in that room with tales from an impossibly glamorous life.

I sat to the side as Janis Burley Wilson, the new president and CEO of the August Wilson Center, gave Mr. Belafonte a sneak preview of some of the questions members of the audience would ask during the Q&A later that night.

Charlene Foggie-Barnett, the archive specialist for the Teenie Harris Archives at the Carnegie Museum of Art, tried to prompt his memory about where pictures taken of him by the famed photographer in the Hill District decades go were staged. She also presented him with a book of Teenie's photos that absolutely delighted him.

Me? I had no gifts to bring. All I really wanted was a photo with Harry Belafonte, but after seeing how much he teased and hassled Charlene and Janis when they asked to do "selfies" with him, I thought better of it.

After relenting to their request, he then photo-bombed the session by smiling playfully like the Joker and making faces instead of being totally cooperative. I don't remember who said it, but I'm sure I heard one of the women mutter "now you're just being silly."

It made me laugh out loud to see Harry Belafonte, the first man to sell a million records, casting superstar decorum aside to make mischief. We were the only men in the room, which is probably why we laughed so hard.

A half hour later, Mr. Belafonte, dressed in a gray suit and navy turtleneck and carrying a cane, was lead to one of two red chairs on the stage by hip-hop activist Jasiri X., who could easily be mistaken for one of his sons. He tipped the baseball cap he was wearing to a thunderous standing ovation.

What followed was one of the most moving evenings I think I've ever experienced in Pittsburgh. He shared the news that he'd had a stroke recently, so this was probably his last public appearance. His voice was strong, but husky. Still, the anecdotes rolled off his tongue like fire.

Mr. Belafonte effortlessly recalled his hardscrabble youth in Harlem and Jamaica, giving credit to his single mom for keeping him in line. "Never come upon an injustice you do not pause to fix," he said, mimicking her Jamaican accent.

His life with all of its twists and turns -- poverty, sudden fame, McCarthyism, civil rights activism, a dire prediction about fascism in America -- was laid bare on the stage.

He shared one final anecdote before leaving the stage. It was about a dispirited MLK days before he was assassinated, privately confessing to aides that those pushing him to become more radical had a point. MLK agreed that the civil rights movement was asking blacks to integrate "into a burning house." When asked what their strategy should be going forward, MLK reportedly said, "We just have to become firemen."

With that, the 90-year-old performer waved a final goodbye to the audience before he was led from the stage and into history's grateful embrace.

Dear Common Dreams reader, The U.S. is on a fast track to authoritarianism like nothing I've ever seen. Meanwhile, corporate news outlets are utterly capitulating to Trump, twisting their coverage to avoid drawing his ire while lining up to stuff cash in his pockets. That's why I believe that Common Dreams is doing the best and most consequential reporting that we've ever done. Our small but mighty team is a progressive reporting powerhouse, covering the news every day that the corporate media never will. Our mission has always been simple: To inform. To inspire. And to ignite change for the common good. Now here's the key piece that I want all our readers to understand: None of this would be possible without your financial support. That's not just some fundraising cliche. It's the absolute and literal truth. We don't accept corporate advertising and never will. We don't have a paywall because we don't think people should be blocked from critical news based on their ability to pay. Everything we do is funded by the donations of readers like you. Will you donate now to help power the nonprofit, independent reporting of Common Dreams? Thank you for being a vital member of our community. Together, we can keep independent journalism alive when it’s needed most. - Craig Brown, Co-founder |

Activist and artist Harry Belafonte could be sitting or standing when you meet him, but he's usually the only true giant in the room. Meeting Mr. Belafonte and his wife, Pamela, in the green room of the Carnegie Music Hall last Friday was a perk resulting from having interviewed him by phone the week before.

Mr. Belafonte was in Pittsburgh ostensibly to give a speech about the state of civil rights and black politics. The truth is that he could've come to town to read from the phone book and still attracted the 1,000 people who turned up for what he would call on stage later that night his "last public appearance."

When he extended his hand in the green room, I was struck by the fact that it was the same hand that had gripped Paul Robeson's and Eleanor Roosevelt's in gratitude for their mentorship in the 1940s. It was the same hand that clasped Martin Luther King's in friendship in the early 1950s, years before he was the civil rights leader he would eventually become.

When you shake hands with Mr. Belafonte, you're one degree of separation from Charlie Parker, Miles Davis and Lester Young at the Royal Roost giving advice to an earnest young singer who had until recently been a janitor's assistant in Harlem.

When Harry Belafonte smiles at you, you wonder if the magnetism radiating from him in torrents is something his fellow thespians Marlon Brando, Tony Curtis, Bea Arthur and Sidney Poitier recognized when they all took acting workshops together in Greenwich Village in the postwar years.

If you can avoid a sense of giddiness having your hand clasped by a man who shook hands with Woody Guthrie and Leadbelly after catching them in concert at the Village Vanguard, then you're blessed with a less imposing sense of history than I am.

After all, this was the same hand that James Baldwin shook. It was these fingers that caressed Dorothy Dandridge's cheeks in "Carmen Jones." It belongs to the man who gave Bob Dylan his first professional recording gig. Coretta Scott King cried on this man's shoulders after her husband was assassinated. Decades later, Nelson Mandela would embrace him in revolutionary solidarity for producing music that helped keep him alive. I was shaking hands with a man who constantly stood at the apex of American history.

I don't often find myself at a loss for words around famous people, but somehow I kept my prattling to a minimum while he regaled the four of us in that room with tales from an impossibly glamorous life.

I sat to the side as Janis Burley Wilson, the new president and CEO of the August Wilson Center, gave Mr. Belafonte a sneak preview of some of the questions members of the audience would ask during the Q&A later that night.

Charlene Foggie-Barnett, the archive specialist for the Teenie Harris Archives at the Carnegie Museum of Art, tried to prompt his memory about where pictures taken of him by the famed photographer in the Hill District decades go were staged. She also presented him with a book of Teenie's photos that absolutely delighted him.

Me? I had no gifts to bring. All I really wanted was a photo with Harry Belafonte, but after seeing how much he teased and hassled Charlene and Janis when they asked to do "selfies" with him, I thought better of it.

After relenting to their request, he then photo-bombed the session by smiling playfully like the Joker and making faces instead of being totally cooperative. I don't remember who said it, but I'm sure I heard one of the women mutter "now you're just being silly."

It made me laugh out loud to see Harry Belafonte, the first man to sell a million records, casting superstar decorum aside to make mischief. We were the only men in the room, which is probably why we laughed so hard.

A half hour later, Mr. Belafonte, dressed in a gray suit and navy turtleneck and carrying a cane, was lead to one of two red chairs on the stage by hip-hop activist Jasiri X., who could easily be mistaken for one of his sons. He tipped the baseball cap he was wearing to a thunderous standing ovation.

What followed was one of the most moving evenings I think I've ever experienced in Pittsburgh. He shared the news that he'd had a stroke recently, so this was probably his last public appearance. His voice was strong, but husky. Still, the anecdotes rolled off his tongue like fire.

Mr. Belafonte effortlessly recalled his hardscrabble youth in Harlem and Jamaica, giving credit to his single mom for keeping him in line. "Never come upon an injustice you do not pause to fix," he said, mimicking her Jamaican accent.

His life with all of its twists and turns -- poverty, sudden fame, McCarthyism, civil rights activism, a dire prediction about fascism in America -- was laid bare on the stage.

He shared one final anecdote before leaving the stage. It was about a dispirited MLK days before he was assassinated, privately confessing to aides that those pushing him to become more radical had a point. MLK agreed that the civil rights movement was asking blacks to integrate "into a burning house." When asked what their strategy should be going forward, MLK reportedly said, "We just have to become firemen."

With that, the 90-year-old performer waved a final goodbye to the audience before he was led from the stage and into history's grateful embrace.

Activist and artist Harry Belafonte could be sitting or standing when you meet him, but he's usually the only true giant in the room. Meeting Mr. Belafonte and his wife, Pamela, in the green room of the Carnegie Music Hall last Friday was a perk resulting from having interviewed him by phone the week before.

Mr. Belafonte was in Pittsburgh ostensibly to give a speech about the state of civil rights and black politics. The truth is that he could've come to town to read from the phone book and still attracted the 1,000 people who turned up for what he would call on stage later that night his "last public appearance."

When he extended his hand in the green room, I was struck by the fact that it was the same hand that had gripped Paul Robeson's and Eleanor Roosevelt's in gratitude for their mentorship in the 1940s. It was the same hand that clasped Martin Luther King's in friendship in the early 1950s, years before he was the civil rights leader he would eventually become.

When you shake hands with Mr. Belafonte, you're one degree of separation from Charlie Parker, Miles Davis and Lester Young at the Royal Roost giving advice to an earnest young singer who had until recently been a janitor's assistant in Harlem.

When Harry Belafonte smiles at you, you wonder if the magnetism radiating from him in torrents is something his fellow thespians Marlon Brando, Tony Curtis, Bea Arthur and Sidney Poitier recognized when they all took acting workshops together in Greenwich Village in the postwar years.

If you can avoid a sense of giddiness having your hand clasped by a man who shook hands with Woody Guthrie and Leadbelly after catching them in concert at the Village Vanguard, then you're blessed with a less imposing sense of history than I am.

After all, this was the same hand that James Baldwin shook. It was these fingers that caressed Dorothy Dandridge's cheeks in "Carmen Jones." It belongs to the man who gave Bob Dylan his first professional recording gig. Coretta Scott King cried on this man's shoulders after her husband was assassinated. Decades later, Nelson Mandela would embrace him in revolutionary solidarity for producing music that helped keep him alive. I was shaking hands with a man who constantly stood at the apex of American history.

I don't often find myself at a loss for words around famous people, but somehow I kept my prattling to a minimum while he regaled the four of us in that room with tales from an impossibly glamorous life.

I sat to the side as Janis Burley Wilson, the new president and CEO of the August Wilson Center, gave Mr. Belafonte a sneak preview of some of the questions members of the audience would ask during the Q&A later that night.

Charlene Foggie-Barnett, the archive specialist for the Teenie Harris Archives at the Carnegie Museum of Art, tried to prompt his memory about where pictures taken of him by the famed photographer in the Hill District decades go were staged. She also presented him with a book of Teenie's photos that absolutely delighted him.

Me? I had no gifts to bring. All I really wanted was a photo with Harry Belafonte, but after seeing how much he teased and hassled Charlene and Janis when they asked to do "selfies" with him, I thought better of it.

After relenting to their request, he then photo-bombed the session by smiling playfully like the Joker and making faces instead of being totally cooperative. I don't remember who said it, but I'm sure I heard one of the women mutter "now you're just being silly."

It made me laugh out loud to see Harry Belafonte, the first man to sell a million records, casting superstar decorum aside to make mischief. We were the only men in the room, which is probably why we laughed so hard.

A half hour later, Mr. Belafonte, dressed in a gray suit and navy turtleneck and carrying a cane, was lead to one of two red chairs on the stage by hip-hop activist Jasiri X., who could easily be mistaken for one of his sons. He tipped the baseball cap he was wearing to a thunderous standing ovation.

What followed was one of the most moving evenings I think I've ever experienced in Pittsburgh. He shared the news that he'd had a stroke recently, so this was probably his last public appearance. His voice was strong, but husky. Still, the anecdotes rolled off his tongue like fire.

Mr. Belafonte effortlessly recalled his hardscrabble youth in Harlem and Jamaica, giving credit to his single mom for keeping him in line. "Never come upon an injustice you do not pause to fix," he said, mimicking her Jamaican accent.

His life with all of its twists and turns -- poverty, sudden fame, McCarthyism, civil rights activism, a dire prediction about fascism in America -- was laid bare on the stage.

He shared one final anecdote before leaving the stage. It was about a dispirited MLK days before he was assassinated, privately confessing to aides that those pushing him to become more radical had a point. MLK agreed that the civil rights movement was asking blacks to integrate "into a burning house." When asked what their strategy should be going forward, MLK reportedly said, "We just have to become firemen."

With that, the 90-year-old performer waved a final goodbye to the audience before he was led from the stage and into history's grateful embrace.