#FreeAJStaff: Travesty of Justice Continues

Egyptian judges act on their own in terms of repressing whomever they perceive as status quo critics.

"Shocked", "sickened", and "appalled" were appropriate words to describe the international reactions - and some of the local ones - to the second sentencing of Al Jazeera journalists and their colleagues in a Cairo court on Saturday.

"The verdict today ... sends a message that journalists can be locked up for simply doing their job, for telling the truth, and reporting the news. And it sends a dangerous message that there are judges in Egypt who will allow their courts to become instruments of political repression and propaganda."

Those were words of Mohamed Fahmy's lawyer, Amal Clooney.

The more disturbing part is that her words are an understatement. The Committee to Protect Journalists issued a report in June 2015 that concluded that Egypt's imprisonment of journalists is at an all-time high.

Earlier in February, the Euro-Mediterranean Human Rights Monitor published a letter in which the names of 101 detained journalists were listed, followed by an updated report in August 2015 entitled "Practicing Journalism in Egypt is 'Risky Business'".

The plight of Al Jazeera's journalists is deeply embedded in Egypt's crisis.

The post-July 2013 regime is characterised by a hawkish military-style nature. It indeed tightened the room for any alternative narrative or independent reporting, even when compared to the heydays of Mubarak.

And if journalists did not toe the "official" line (ie the military and their appointees' statements), they can be subjected to legal consequences.

This is not a new development under the newly ratified and enforced "anti-terrorism" law.

This has been a policy choice since July 2013 and is enforced systematically and with impunity by various tools and institutions, particularly during and in the aftermath of the Rabaa massacre in August 2013.

The judiciary was indeed one of the tools: in particular, the judges of the so-called "counterterrorism judicial circles" that tried Al Jazeera journalists among many others.

Those judges were thoroughly selected.

Many come from a state security or other police department backgrounds. Others are well known within the judicial circles to be among the "hawks" of the judiciary.

They have very strong political inclinations, and at the core of them, a very negative perception of the January 2011 uprising. And accordingly, these judges do not need political directives from the ruling executive.

They act on their own in terms of repressing whomever they perceive as "status quo" critics.

Judge Hassan Farid of the Al Jazeera trial, for example, has sentenced many pro-January 2011 revolution leftist activists (such as Alaa Abdel Fattah), pro-January and anti-coup Muslim Brotherhood activists, and also suspected members of armed Islamist organisations.

This is despite that in many of these cases the only legal evidence presented is a written report from a junior officer in the national security apparatus.

But this does not mean the end of the legal process for Al Jazeera journalists.

There is a second and a final appeal chance at Egypt's highest appeal body, the Court of Cassation. But the latter is not immune from the aforementioned structural problems and, of course, from the executive's inclinations and whims.

Politically, part of the crisis and its repercussions on journalists so far is that there are only negligible costs for unchecked repression.

If a political regime can kill more than one thousand protesters in less than ten hours - live, in front of international media - and get away with it, it can certainly prosecute the journalists who reported the violations without worries.

Hence, if the impunity continues, the cost-free repression is more likely to continue, at least in the short to mid-term.

This should be understood as a calculated policy choice, based on the current local and international environment, and not as an ad hoc arrangement for a specific situation.

I know. More disturbing, I am afraid.

Peter Greste, Mohamed Fahmy, and Baher Mohamed became household names. And regardless of the future developments, they will always symbolise independent journalism facing incredible injustice.

But in such a repressive context, international media should not forget about the rest of the victims.

While television cameras were haunting Amal Clooney, Fahmy's international lawyer and the wife of Hollywood actor George Clooney, a student "defendant", Shadi Ibrahim, was awaiting his fate.

He had no one around him, just a Quran in his hand. The painful picture is a reminder of the many victims that the international media forgot.

An Urgent Message From Our Co-Founder

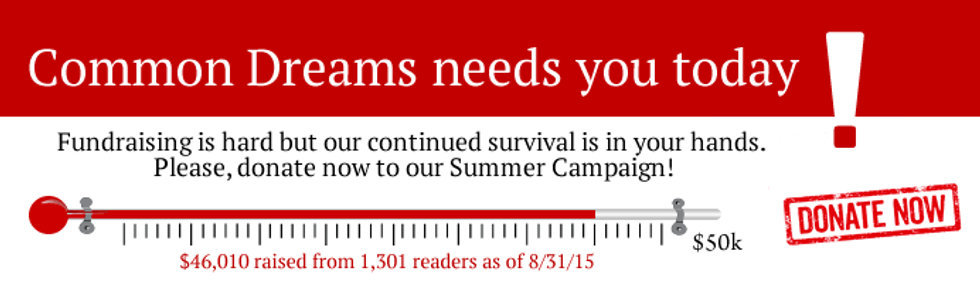

Dear Common Dreams reader, The U.S. is on a fast track to authoritarianism like nothing I've ever seen. Meanwhile, corporate news outlets are utterly capitulating to Trump, twisting their coverage to avoid drawing his ire while lining up to stuff cash in his pockets. That's why I believe that Common Dreams is doing the best and most consequential reporting that we've ever done. Our small but mighty team is a progressive reporting powerhouse, covering the news every day that the corporate media never will. Our mission has always been simple: To inform. To inspire. And to ignite change for the common good. Now here's the key piece that I want all our readers to understand: None of this would be possible without your financial support. That's not just some fundraising cliche. It's the absolute and literal truth. We don't accept corporate advertising and never will. We don't have a paywall because we don't think people should be blocked from critical news based on their ability to pay. Everything we do is funded by the donations of readers like you. Will you donate now to help power the nonprofit, independent reporting of Common Dreams? Thank you for being a vital member of our community. Together, we can keep independent journalism alive when it’s needed most. - Craig Brown, Co-founder |

"Shocked", "sickened", and "appalled" were appropriate words to describe the international reactions - and some of the local ones - to the second sentencing of Al Jazeera journalists and their colleagues in a Cairo court on Saturday.

"The verdict today ... sends a message that journalists can be locked up for simply doing their job, for telling the truth, and reporting the news. And it sends a dangerous message that there are judges in Egypt who will allow their courts to become instruments of political repression and propaganda."

Those were words of Mohamed Fahmy's lawyer, Amal Clooney.

The more disturbing part is that her words are an understatement. The Committee to Protect Journalists issued a report in June 2015 that concluded that Egypt's imprisonment of journalists is at an all-time high.

Earlier in February, the Euro-Mediterranean Human Rights Monitor published a letter in which the names of 101 detained journalists were listed, followed by an updated report in August 2015 entitled "Practicing Journalism in Egypt is 'Risky Business'".

The plight of Al Jazeera's journalists is deeply embedded in Egypt's crisis.

The post-July 2013 regime is characterised by a hawkish military-style nature. It indeed tightened the room for any alternative narrative or independent reporting, even when compared to the heydays of Mubarak.

And if journalists did not toe the "official" line (ie the military and their appointees' statements), they can be subjected to legal consequences.

This is not a new development under the newly ratified and enforced "anti-terrorism" law.

This has been a policy choice since July 2013 and is enforced systematically and with impunity by various tools and institutions, particularly during and in the aftermath of the Rabaa massacre in August 2013.

The judiciary was indeed one of the tools: in particular, the judges of the so-called "counterterrorism judicial circles" that tried Al Jazeera journalists among many others.

Those judges were thoroughly selected.

Many come from a state security or other police department backgrounds. Others are well known within the judicial circles to be among the "hawks" of the judiciary.

They have very strong political inclinations, and at the core of them, a very negative perception of the January 2011 uprising. And accordingly, these judges do not need political directives from the ruling executive.

They act on their own in terms of repressing whomever they perceive as "status quo" critics.

Judge Hassan Farid of the Al Jazeera trial, for example, has sentenced many pro-January 2011 revolution leftist activists (such as Alaa Abdel Fattah), pro-January and anti-coup Muslim Brotherhood activists, and also suspected members of armed Islamist organisations.

This is despite that in many of these cases the only legal evidence presented is a written report from a junior officer in the national security apparatus.

But this does not mean the end of the legal process for Al Jazeera journalists.

There is a second and a final appeal chance at Egypt's highest appeal body, the Court of Cassation. But the latter is not immune from the aforementioned structural problems and, of course, from the executive's inclinations and whims.

Politically, part of the crisis and its repercussions on journalists so far is that there are only negligible costs for unchecked repression.

If a political regime can kill more than one thousand protesters in less than ten hours - live, in front of international media - and get away with it, it can certainly prosecute the journalists who reported the violations without worries.

Hence, if the impunity continues, the cost-free repression is more likely to continue, at least in the short to mid-term.

This should be understood as a calculated policy choice, based on the current local and international environment, and not as an ad hoc arrangement for a specific situation.

I know. More disturbing, I am afraid.

Peter Greste, Mohamed Fahmy, and Baher Mohamed became household names. And regardless of the future developments, they will always symbolise independent journalism facing incredible injustice.

But in such a repressive context, international media should not forget about the rest of the victims.

While television cameras were haunting Amal Clooney, Fahmy's international lawyer and the wife of Hollywood actor George Clooney, a student "defendant", Shadi Ibrahim, was awaiting his fate.

He had no one around him, just a Quran in his hand. The painful picture is a reminder of the many victims that the international media forgot.

"Shocked", "sickened", and "appalled" were appropriate words to describe the international reactions - and some of the local ones - to the second sentencing of Al Jazeera journalists and their colleagues in a Cairo court on Saturday.

"The verdict today ... sends a message that journalists can be locked up for simply doing their job, for telling the truth, and reporting the news. And it sends a dangerous message that there are judges in Egypt who will allow their courts to become instruments of political repression and propaganda."

Those were words of Mohamed Fahmy's lawyer, Amal Clooney.

The more disturbing part is that her words are an understatement. The Committee to Protect Journalists issued a report in June 2015 that concluded that Egypt's imprisonment of journalists is at an all-time high.

Earlier in February, the Euro-Mediterranean Human Rights Monitor published a letter in which the names of 101 detained journalists were listed, followed by an updated report in August 2015 entitled "Practicing Journalism in Egypt is 'Risky Business'".

The plight of Al Jazeera's journalists is deeply embedded in Egypt's crisis.

The post-July 2013 regime is characterised by a hawkish military-style nature. It indeed tightened the room for any alternative narrative or independent reporting, even when compared to the heydays of Mubarak.

And if journalists did not toe the "official" line (ie the military and their appointees' statements), they can be subjected to legal consequences.

This is not a new development under the newly ratified and enforced "anti-terrorism" law.

This has been a policy choice since July 2013 and is enforced systematically and with impunity by various tools and institutions, particularly during and in the aftermath of the Rabaa massacre in August 2013.

The judiciary was indeed one of the tools: in particular, the judges of the so-called "counterterrorism judicial circles" that tried Al Jazeera journalists among many others.

Those judges were thoroughly selected.

Many come from a state security or other police department backgrounds. Others are well known within the judicial circles to be among the "hawks" of the judiciary.

They have very strong political inclinations, and at the core of them, a very negative perception of the January 2011 uprising. And accordingly, these judges do not need political directives from the ruling executive.

They act on their own in terms of repressing whomever they perceive as "status quo" critics.

Judge Hassan Farid of the Al Jazeera trial, for example, has sentenced many pro-January 2011 revolution leftist activists (such as Alaa Abdel Fattah), pro-January and anti-coup Muslim Brotherhood activists, and also suspected members of armed Islamist organisations.

This is despite that in many of these cases the only legal evidence presented is a written report from a junior officer in the national security apparatus.

But this does not mean the end of the legal process for Al Jazeera journalists.

There is a second and a final appeal chance at Egypt's highest appeal body, the Court of Cassation. But the latter is not immune from the aforementioned structural problems and, of course, from the executive's inclinations and whims.

Politically, part of the crisis and its repercussions on journalists so far is that there are only negligible costs for unchecked repression.

If a political regime can kill more than one thousand protesters in less than ten hours - live, in front of international media - and get away with it, it can certainly prosecute the journalists who reported the violations without worries.

Hence, if the impunity continues, the cost-free repression is more likely to continue, at least in the short to mid-term.

This should be understood as a calculated policy choice, based on the current local and international environment, and not as an ad hoc arrangement for a specific situation.

I know. More disturbing, I am afraid.

Peter Greste, Mohamed Fahmy, and Baher Mohamed became household names. And regardless of the future developments, they will always symbolise independent journalism facing incredible injustice.

But in such a repressive context, international media should not forget about the rest of the victims.

While television cameras were haunting Amal Clooney, Fahmy's international lawyer and the wife of Hollywood actor George Clooney, a student "defendant", Shadi Ibrahim, was awaiting his fate.

He had no one around him, just a Quran in his hand. The painful picture is a reminder of the many victims that the international media forgot.