SUBSCRIBE TO OUR FREE NEWSLETTER

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

5

#000000

#FFFFFF

To donate by check, phone, or other method, see our More Ways to Give page.

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

Last Monday, President Obama commuted the sentences of 46 non-violent drug offenders. While doing so, he highlighted what he believed to be the harsh sentencing guidelines that kept these men and women in prison. These commutations, President Obama's recent speech at the NAACP Convention in Philadelphia, and his Thursday visit to the El Reno Correctional Institution in Oklahoma represent the latest moves in his push for criminal justice reform. It has also sparked some spirited debate on incarceration here, here, and here.

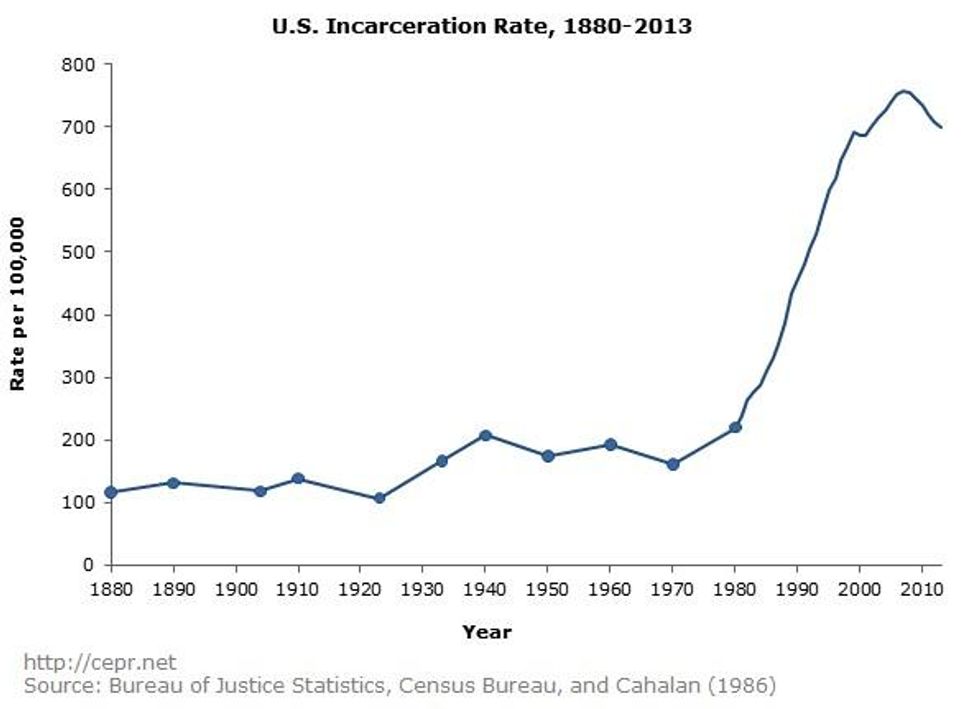

As President Obama and others have mentioned, the incarceration rate has fallen over the past few years. After almost 30 years of steady increases, the incarceration rate peaked at 757.7 in 2007, and fell to 698.7 by the end of 2013.[i] This is certainly promising news, especially if this trend continues.

Criminal justice reform shouldn't end with improving conditions in prisons and jails and getting rid of overly harsh sentencing laws. We must also consider what happens to these men and women once they're released. Will they be able to find jobs? Will they be able to vote? How about receive public assistance? In many cases, the answer to these questions is no.

Criminal justice reform shouldn't end with improving conditions in prisons and jails and getting rid of overly harsh sentencing laws.Research has shown that having to declare your criminal history on job applications decreases your chances of continuing in the hiring process. 19 states restrict voting rights while ex-offenders are on parole or probation, and 12 of them keep these restrictions in place for some crimes, even after the ex-offenders are off of parole or probation. Also, many drug offenders face bans on access to public assistance in the form of cash benefits (TANF or Temporary Assistance to Needy Families) and SNAP (Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, or food stamps).

Given the large number of prisoners currently incarcerated, it is likely that it will be many years before the ex-prisoner population begins to noticeably decrease. It is imperative that we take the necessary steps to ensure that these ex-offenders have the tools they need to be successful once they are released.

Dear Common Dreams reader, The U.S. is on a fast track to authoritarianism like nothing I've ever seen. Meanwhile, corporate news outlets are utterly capitulating to Trump, twisting their coverage to avoid drawing his ire while lining up to stuff cash in his pockets. That's why I believe that Common Dreams is doing the best and most consequential reporting that we've ever done. Our small but mighty team is a progressive reporting powerhouse, covering the news every day that the corporate media never will. Our mission has always been simple: To inform. To inspire. And to ignite change for the common good. Now here's the key piece that I want all our readers to understand: None of this would be possible without your financial support. That's not just some fundraising cliche. It's the absolute and literal truth. We don't accept corporate advertising and never will. We don't have a paywall because we don't think people should be blocked from critical news based on their ability to pay. Everything we do is funded by the donations of readers like you. Will you donate now to help power the nonprofit, independent reporting of Common Dreams? Thank you for being a vital member of our community. Together, we can keep independent journalism alive when it’s needed most. - Craig Brown, Co-founder |

Last Monday, President Obama commuted the sentences of 46 non-violent drug offenders. While doing so, he highlighted what he believed to be the harsh sentencing guidelines that kept these men and women in prison. These commutations, President Obama's recent speech at the NAACP Convention in Philadelphia, and his Thursday visit to the El Reno Correctional Institution in Oklahoma represent the latest moves in his push for criminal justice reform. It has also sparked some spirited debate on incarceration here, here, and here.

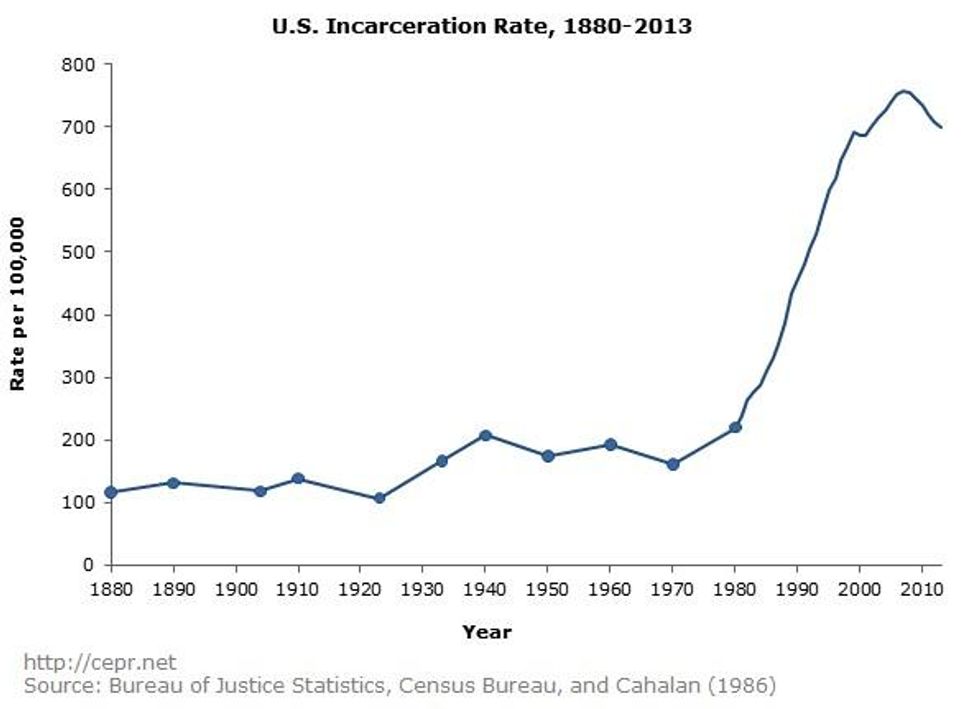

As President Obama and others have mentioned, the incarceration rate has fallen over the past few years. After almost 30 years of steady increases, the incarceration rate peaked at 757.7 in 2007, and fell to 698.7 by the end of 2013.[i] This is certainly promising news, especially if this trend continues.

Criminal justice reform shouldn't end with improving conditions in prisons and jails and getting rid of overly harsh sentencing laws. We must also consider what happens to these men and women once they're released. Will they be able to find jobs? Will they be able to vote? How about receive public assistance? In many cases, the answer to these questions is no.

Criminal justice reform shouldn't end with improving conditions in prisons and jails and getting rid of overly harsh sentencing laws.Research has shown that having to declare your criminal history on job applications decreases your chances of continuing in the hiring process. 19 states restrict voting rights while ex-offenders are on parole or probation, and 12 of them keep these restrictions in place for some crimes, even after the ex-offenders are off of parole or probation. Also, many drug offenders face bans on access to public assistance in the form of cash benefits (TANF or Temporary Assistance to Needy Families) and SNAP (Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, or food stamps).

Given the large number of prisoners currently incarcerated, it is likely that it will be many years before the ex-prisoner population begins to noticeably decrease. It is imperative that we take the necessary steps to ensure that these ex-offenders have the tools they need to be successful once they are released.

Last Monday, President Obama commuted the sentences of 46 non-violent drug offenders. While doing so, he highlighted what he believed to be the harsh sentencing guidelines that kept these men and women in prison. These commutations, President Obama's recent speech at the NAACP Convention in Philadelphia, and his Thursday visit to the El Reno Correctional Institution in Oklahoma represent the latest moves in his push for criminal justice reform. It has also sparked some spirited debate on incarceration here, here, and here.

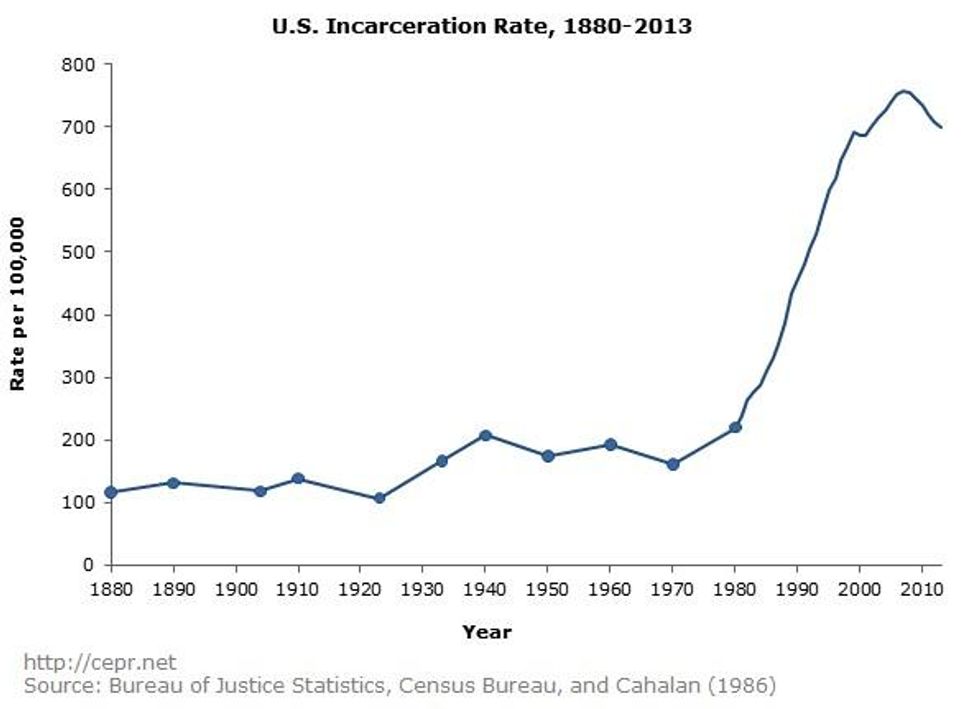

As President Obama and others have mentioned, the incarceration rate has fallen over the past few years. After almost 30 years of steady increases, the incarceration rate peaked at 757.7 in 2007, and fell to 698.7 by the end of 2013.[i] This is certainly promising news, especially if this trend continues.

Criminal justice reform shouldn't end with improving conditions in prisons and jails and getting rid of overly harsh sentencing laws. We must also consider what happens to these men and women once they're released. Will they be able to find jobs? Will they be able to vote? How about receive public assistance? In many cases, the answer to these questions is no.

Criminal justice reform shouldn't end with improving conditions in prisons and jails and getting rid of overly harsh sentencing laws.Research has shown that having to declare your criminal history on job applications decreases your chances of continuing in the hiring process. 19 states restrict voting rights while ex-offenders are on parole or probation, and 12 of them keep these restrictions in place for some crimes, even after the ex-offenders are off of parole or probation. Also, many drug offenders face bans on access to public assistance in the form of cash benefits (TANF or Temporary Assistance to Needy Families) and SNAP (Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, or food stamps).

Given the large number of prisoners currently incarcerated, it is likely that it will be many years before the ex-prisoner population begins to noticeably decrease. It is imperative that we take the necessary steps to ensure that these ex-offenders have the tools they need to be successful once they are released.