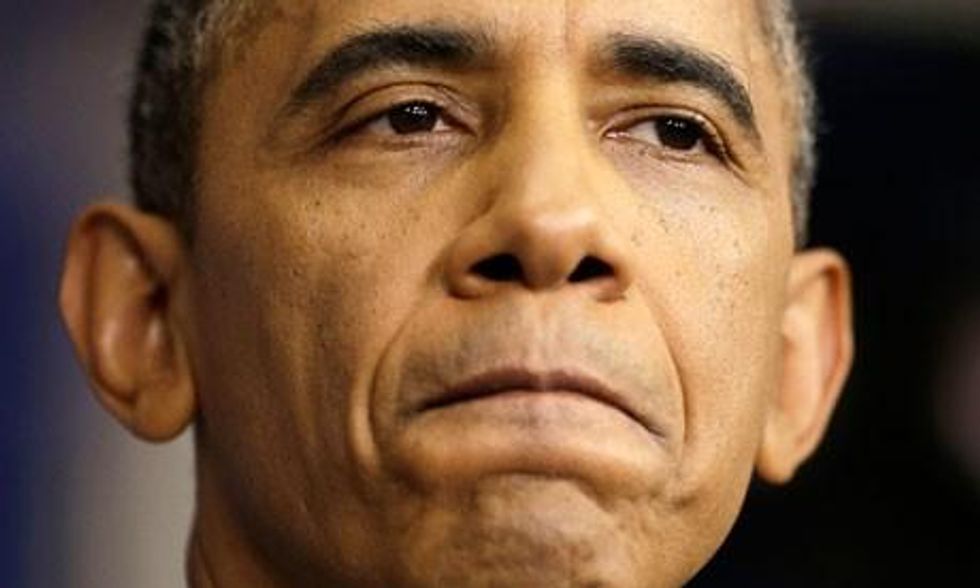

His strategically leaked decision to substitute the term "income inequality" with the more euphemistic "ladders of opportunity" has an any-publicity-is-good-publicity quality to it, of course, as Fox News and other conservative outlets and commentators have leapt upon the substitution as an example of Obama's desperation and weaknesses ("shrinkage" in the provocative phrasing of conservative commentator George Will). They consider it a tacit symbol of the White House surrendering to a public that doesn't really want to talk about income inequality.

But are a lot of poll results indicate that Obama is onto something. If there's a critique to be had about the "pivot", it's not that he's distracting the public from the administration's other problems, it's that his attention to income inequality has not matched the intensity with which Americans are now thinking about it. Gallup reports that 67% of those polled are dissatisfied (39% "very" dissatisfied) with the distribution of wealth in America and 45% are dissatisfied with "opportunities to get ahead by working hard" - both numbers the highest they've been in a decade. Pew tells us that a stunning 69% believe the government should do something about the divide - and 43% say that it should "a lot" of something.

It is true that the massive and growing gap between the rich and poor is not ordinarily a topic of polite (or cable news) conversation. Fox News' recent batch of disingenuous polling took advantage of our societal reticence on the subject. Their poll asked "How do you feel about the fact that some people make a lot more money than others?". Not surprisingly, they found 62% said, "I'm OK with it - that's how our economy works" and another 21% responded, "It stinks, but the government should not get involved."

"Some people make a lot more money than others" is hardly the problem, both in the sense that the question does not address the scope of "a lot more" nor it does not define what it means to "make" it. Most (53%) of the income "earned" - one has to use the term somewhat loosely here - by the top 0.1% richest Americans is not salary for job, but the product of money being made out of money.

The Fox poll does get to one honest premise: up to a point, we take inequality for granted. Indeed, Americans are more sanguine about capitalism's separation of winners and losers than the rest of the world. When asked about it a source of national concern (as opposed to general dissatisfaction) just 47% of Americans say it's a problem. Ironically, we consider it less of a problem than the people of other economically-developed countries do - even though we're the ones with the most alarming disparity. The income ratio of our rich to poor is 16.7%, more than double that of the next most divided country (Spain, at 6.8, where, justifiably, 75% say it's a problem), yet the only country less concerned with income inequality is Australia (33%), whose income ratio is a mere 2.7.

The degree to which Americans are "OK" with income inequality probably depends on their experience with it. Historically, Americans are in denial about both what class they belong to and the differences between the classes: income distribution is about twice as unequal as poll respondents say they think it is.

But reality is sinking in. Americans are starting to discover that they themselves, or friends or a loved ones, have been pushed into the social safety net we used to think was there for someone else. Food stamps, once a symbol of desperate neediness allotted to those unable to fend for themselves, now assist a record number of Americans (one in seven) - and a majority of them are working-age adults. Twenty-eight percent have at least some college education. Foreclosures and unemployment have turned people who had been solidly middle class into sudden homelessness.

In the last decade, wages have stagnated for white-collar, college-educated workers at the same rate as blue-collar workers. In fact, fewer Americans than ever now identify (down to 44% from 53% in 2008) as middle class. Self-identification is catching up with reality.

People understand that the economy has not tanked so much as split in two, with the rich scuttled to the security of lifeboats, likely to be rescued, while the poor and middle class cling to the wreckage. If we're going to go with historical analogies for the current crisis, the Titanic is a lot more fitting than the offensive over-reach to Kristallnacht made by venture capitalist Tom Perkins in the Wall Street Journal over the weekend:

Writing from the epicenter of progressive thought, San Francisco, I would call attention to the parallels of fascist Nazi Germany to its war on its "one percent", namely its Jews, to the progressive war on the American one percent, namely the 'rich'.

At Talking Points Memo, Josh Marshall astutely observes that Perkins' grating folly stems from a combination of "socionomic acrophobia" (a "gulf of estrangement of and alienation") and paranoia. Indeed, the very rich cannot seem to take their attention off their bank acounts long enough to notice that the class struggle is not about them, it's about being poor. Or being just a few rungs of the ladder away from it.

The poor know all about what it's like to be rich, celebrity gossip magazine and reality television shows have seen to that, but the wealthy seem to know nothing, and can't be bothered to find out, about what it's like to poor.

The short version is that it sucks. The longer version is scarier and more precise about outcomes: low-incomes are linked to a lot of rather obvious material and physical outcomes, such as heart disease, diabetes and asthma.

In fact, in the past 30 years, the US has seen a "life expectancy gap" grow in line with the income gap: the poorest among us today can expect to die at the rates they did before the Civil Rights Era, the richest can expect to live five years longer.

Perhaps more surprising, even to those living in the midst of it, is the impact of poverty on relationships - both to self and others: the poor are three times more likely to suffer from mental illness. Being poor knocks off 13 IQ points in terms of being able to address complex problems). Children in poverty are more likely to have their parents' marriage end in divorce and more likely to suffer abuse).

Some conservatives may grasp onto the subject effects of poverty as a way of justifying their preferred method of addressing income inequality: "return to sender", they deserve it. (Among Republicans, 51% say poverty is due to "lack of effort".) But further studies suggest that almost all of the negative effects of poverty are reversible across generations: if you infuse money into a poor family, their children will succeed and be healthier. They will be less likely to need the assistance that supported the generation before them. This not a hypothetical discussion about "welfare culture" versus "entrepreneurism". This is, to coin a phrase, just how our economy could work.

These concrete consequences and results are why Obama's project is not just urgent but eminently practical. We can do something about the income gap. Indeed, many argue that we already have: without what's already been done, the situation today could be even worse. Government intervention practical for another reason as well: if nothing is done to slow down and ultimately reverse the growing gap between rich and poor, Perkins' siege mentality may become less ludicrous - for exactly the reasons he suspects! Doubling down on his Wall Street Journal comments, on Monday he emailed Bloomberg News further thoughts on the state of class struggle in America: "In the Nazi era it was racial demonization, now it is class demonization."

Class has indeed overtaken race as the signature fault in our wealth divide. Researcher Robert Putnam warns:

The class gap over the last 20 years in unmarried births, controlling for race, has doubled, and the racial gap, controlling for class, has been cut in half. Twenty years ago the racial gap was the dominant gap in unmarried births - and now the class gap is by far.

You can see this fault line in still-pitifully pointless war on drugs as well, as working-class non-violent white drug offenders find themselves swept into the same grinding system of punishment, continued addiction, and recidivism - or, just as tragically, they enter the parallel economy of the drug trade.

Conservatives are, in this regard, completely correct about capitalism as a tool of economic advancement; a successful drug dealer is as much an entrepreneur as any other "maker" in America. We just are more aware of the social costs of their business - unlike our stubborn inattention to the costs of a more generalized form of chemical distribution, as in, say, West Virginia.

In other words, the class war could get more radicalized. Imagine the GOP without its southern strategy. Imagine a world where the leader of a new block of activist voters isn't representative of racial equality but of class solidarity. Imagine a free market allowed to run truly free (and the drug laws stay the same). If that time comes, Perkins and his cohort can only wish that it was the Obama government doing the intervention.

If America has in the past had trouble bringing its own attention to the problem of income inequality, it's because people assume that it is not as bad as it is.