SUBSCRIBE TO OUR FREE NEWSLETTER

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

5

#000000

#FFFFFF

To donate by check, phone, or other method, see our More Ways to Give page.

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

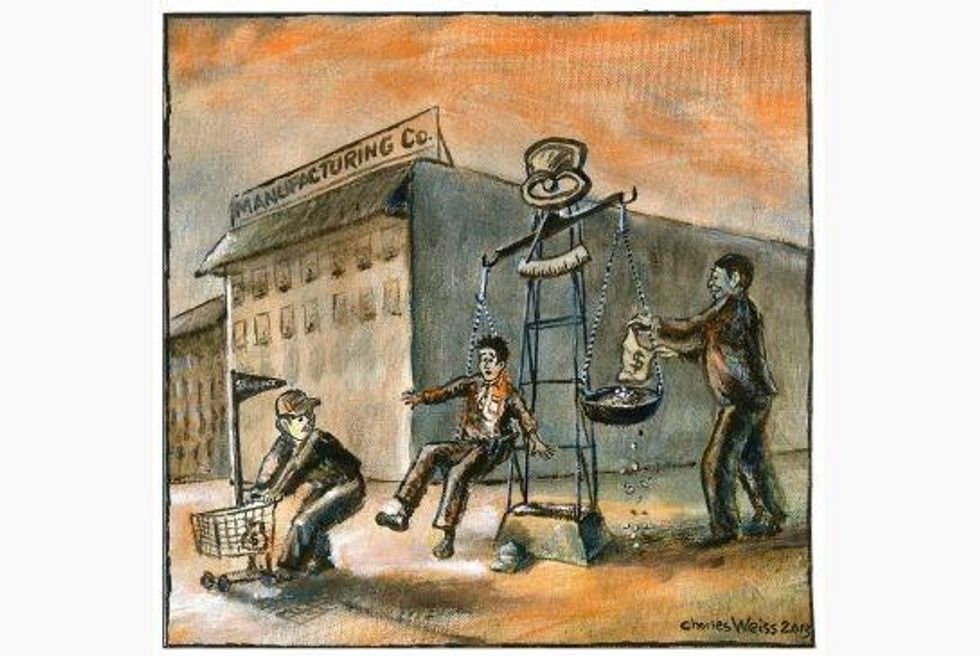

Why is there so much attention paid to people as consumers, but so little to people as workers?

Is it because the mere mention of our rights as workers suggests uncomfortable truths that threaten the very ideological foundations of the current economic system?

Why is there so much attention paid to people as consumers, but so little to people as workers?

Is it because the mere mention of our rights as workers suggests uncomfortable truths that threaten the very ideological foundations of the current economic system?

As we look back on Labor Day, these are important questions to ponder.

The vast majority of us are wageworkers. Wages are our primary source of income. Or we collect a pension because we and/or our spouse were once workers. Or we are dependants of workers.

In fact, a huge proportion of the money spent by consumers in our economy comes directly or indirectly from our wages as workers.

Despite this obvious reality, while the media is packed with material about consumer rights, consumer choice, ads claiming the best price for consumers and politicians such as the industry minister claiming "to do what's best for consumers," there is seldom mention of workers' rights except when it concerns strikes or other "disruptions" to the economy. It's as if workers are mere cogs in a giant machine, only worth discussing when a breakdown occurs. There's no profit to be made promoting workers' rights; in fact, we are seen primarily as a cost.

Occasionally there is some lip service given to workers as a resource; words to the effect that "we're all in this together" might be spoken, but if workers were truly valued as people, wouldn't there be at least some semblance of democracy at work?

Instead, the master-servant relationship is the legal framework that dominates under our current economic system.

Reality for most at work is a fundamental lack of respect. That's why "the system" prefers to focus on us as consumers rather than as workers.

So what, one might ask? What's the big deal if workers must give up being treated as equal human beings, so long as we are well paid? The object of work is to make enough money so that we can consume what we want and enjoy the good life, nothing more.

Aside from the fact many of us are not well paid, the answer to the question "so what?" is that work is an essential element of human identity. When asked at a party, "what do you do?" not many of us answer: "I shop." And if we did, what would that say about us?

What we do -- work -- is what defines us, what makes us human. We want a job that is a source of meaning, not simply consumption. The renaissance in artisanal production -- butchers, bakers, candlestick makers etc. -- is in part a sign of this need for authentic work.

When work does not provide satisfaction alienation is the result. This leads to stress, addictions and other forms of ill health.

Even some unions become complicit in this alienation, focusing exclusively on squeezing out more money, in essence agreeing that what really counts is consuming.

Neo-conservatives want us to care only about making more money, about consuming more, yet they argue we should earn less. Of course this is a ridiculous contradiction. Smarter capitalists are Keynesians. They want workers to demand more and to spend more. But we've reached the limit of Keynesianism in two senses: Capitalists have abandoned it, so appeals for its return are a pathetic dead end. And even if the capitalists were willing to give us more, more has become an environmental dead end.

Instead, workers and their unions must learn to dream bigger. We must learn to demand more than simply being able to buy more stuff.

We need to marry the growing desire for authentic work, to define ourselves by what we do, with a wider vision of changing our economic system. Workers demanding greater control of their jobs can lead to a better world for all.

Dear Common Dreams reader, The U.S. is on a fast track to authoritarianism like nothing I've ever seen. Meanwhile, corporate news outlets are utterly capitulating to Trump, twisting their coverage to avoid drawing his ire while lining up to stuff cash in his pockets. That's why I believe that Common Dreams is doing the best and most consequential reporting that we've ever done. Our small but mighty team is a progressive reporting powerhouse, covering the news every day that the corporate media never will. Our mission has always been simple: To inform. To inspire. And to ignite change for the common good. Now here's the key piece that I want all our readers to understand: None of this would be possible without your financial support. That's not just some fundraising cliche. It's the absolute and literal truth. We don't accept corporate advertising and never will. We don't have a paywall because we don't think people should be blocked from critical news based on their ability to pay. Everything we do is funded by the donations of readers like you. Will you donate now to help power the nonprofit, independent reporting of Common Dreams? Thank you for being a vital member of our community. Together, we can keep independent journalism alive when it’s needed most. - Craig Brown, Co-founder |

Why is there so much attention paid to people as consumers, but so little to people as workers?

Is it because the mere mention of our rights as workers suggests uncomfortable truths that threaten the very ideological foundations of the current economic system?

As we look back on Labor Day, these are important questions to ponder.

The vast majority of us are wageworkers. Wages are our primary source of income. Or we collect a pension because we and/or our spouse were once workers. Or we are dependants of workers.

In fact, a huge proportion of the money spent by consumers in our economy comes directly or indirectly from our wages as workers.

Despite this obvious reality, while the media is packed with material about consumer rights, consumer choice, ads claiming the best price for consumers and politicians such as the industry minister claiming "to do what's best for consumers," there is seldom mention of workers' rights except when it concerns strikes or other "disruptions" to the economy. It's as if workers are mere cogs in a giant machine, only worth discussing when a breakdown occurs. There's no profit to be made promoting workers' rights; in fact, we are seen primarily as a cost.

Occasionally there is some lip service given to workers as a resource; words to the effect that "we're all in this together" might be spoken, but if workers were truly valued as people, wouldn't there be at least some semblance of democracy at work?

Instead, the master-servant relationship is the legal framework that dominates under our current economic system.

Reality for most at work is a fundamental lack of respect. That's why "the system" prefers to focus on us as consumers rather than as workers.

So what, one might ask? What's the big deal if workers must give up being treated as equal human beings, so long as we are well paid? The object of work is to make enough money so that we can consume what we want and enjoy the good life, nothing more.

Aside from the fact many of us are not well paid, the answer to the question "so what?" is that work is an essential element of human identity. When asked at a party, "what do you do?" not many of us answer: "I shop." And if we did, what would that say about us?

What we do -- work -- is what defines us, what makes us human. We want a job that is a source of meaning, not simply consumption. The renaissance in artisanal production -- butchers, bakers, candlestick makers etc. -- is in part a sign of this need for authentic work.

When work does not provide satisfaction alienation is the result. This leads to stress, addictions and other forms of ill health.

Even some unions become complicit in this alienation, focusing exclusively on squeezing out more money, in essence agreeing that what really counts is consuming.

Neo-conservatives want us to care only about making more money, about consuming more, yet they argue we should earn less. Of course this is a ridiculous contradiction. Smarter capitalists are Keynesians. They want workers to demand more and to spend more. But we've reached the limit of Keynesianism in two senses: Capitalists have abandoned it, so appeals for its return are a pathetic dead end. And even if the capitalists were willing to give us more, more has become an environmental dead end.

Instead, workers and their unions must learn to dream bigger. We must learn to demand more than simply being able to buy more stuff.

We need to marry the growing desire for authentic work, to define ourselves by what we do, with a wider vision of changing our economic system. Workers demanding greater control of their jobs can lead to a better world for all.

Why is there so much attention paid to people as consumers, but so little to people as workers?

Is it because the mere mention of our rights as workers suggests uncomfortable truths that threaten the very ideological foundations of the current economic system?

As we look back on Labor Day, these are important questions to ponder.

The vast majority of us are wageworkers. Wages are our primary source of income. Or we collect a pension because we and/or our spouse were once workers. Or we are dependants of workers.

In fact, a huge proportion of the money spent by consumers in our economy comes directly or indirectly from our wages as workers.

Despite this obvious reality, while the media is packed with material about consumer rights, consumer choice, ads claiming the best price for consumers and politicians such as the industry minister claiming "to do what's best for consumers," there is seldom mention of workers' rights except when it concerns strikes or other "disruptions" to the economy. It's as if workers are mere cogs in a giant machine, only worth discussing when a breakdown occurs. There's no profit to be made promoting workers' rights; in fact, we are seen primarily as a cost.

Occasionally there is some lip service given to workers as a resource; words to the effect that "we're all in this together" might be spoken, but if workers were truly valued as people, wouldn't there be at least some semblance of democracy at work?

Instead, the master-servant relationship is the legal framework that dominates under our current economic system.

Reality for most at work is a fundamental lack of respect. That's why "the system" prefers to focus on us as consumers rather than as workers.

So what, one might ask? What's the big deal if workers must give up being treated as equal human beings, so long as we are well paid? The object of work is to make enough money so that we can consume what we want and enjoy the good life, nothing more.

Aside from the fact many of us are not well paid, the answer to the question "so what?" is that work is an essential element of human identity. When asked at a party, "what do you do?" not many of us answer: "I shop." And if we did, what would that say about us?

What we do -- work -- is what defines us, what makes us human. We want a job that is a source of meaning, not simply consumption. The renaissance in artisanal production -- butchers, bakers, candlestick makers etc. -- is in part a sign of this need for authentic work.

When work does not provide satisfaction alienation is the result. This leads to stress, addictions and other forms of ill health.

Even some unions become complicit in this alienation, focusing exclusively on squeezing out more money, in essence agreeing that what really counts is consuming.

Neo-conservatives want us to care only about making more money, about consuming more, yet they argue we should earn less. Of course this is a ridiculous contradiction. Smarter capitalists are Keynesians. They want workers to demand more and to spend more. But we've reached the limit of Keynesianism in two senses: Capitalists have abandoned it, so appeals for its return are a pathetic dead end. And even if the capitalists were willing to give us more, more has become an environmental dead end.

Instead, workers and their unions must learn to dream bigger. We must learn to demand more than simply being able to buy more stuff.

We need to marry the growing desire for authentic work, to define ourselves by what we do, with a wider vision of changing our economic system. Workers demanding greater control of their jobs can lead to a better world for all.