SUBSCRIBE TO OUR FREE NEWSLETTER

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

5

#000000

#FFFFFF

To donate by check, phone, or other method, see our More Ways to Give page.

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

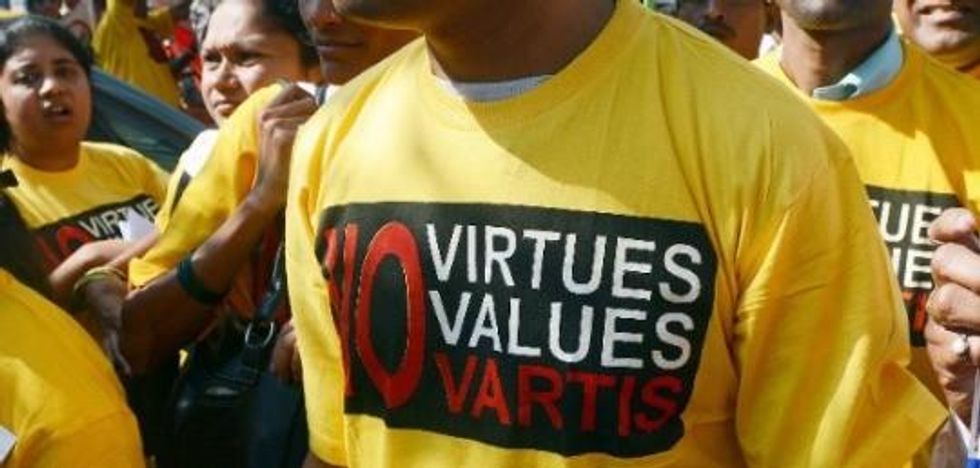

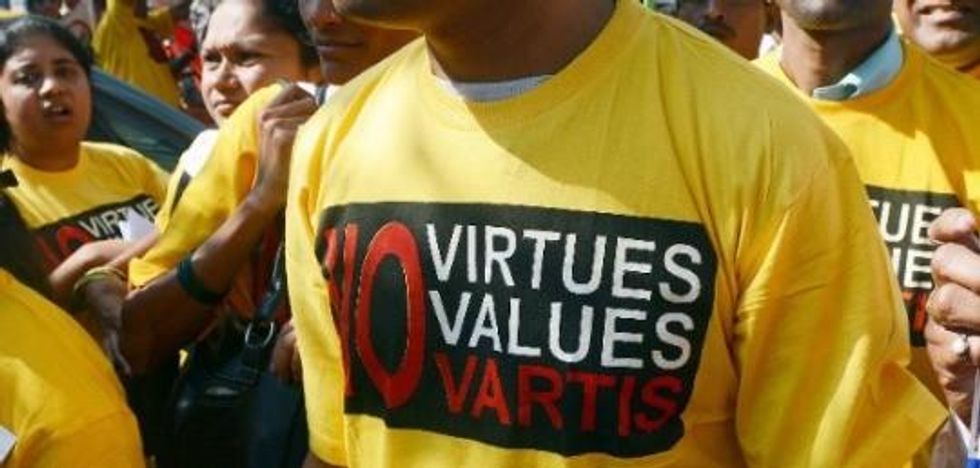

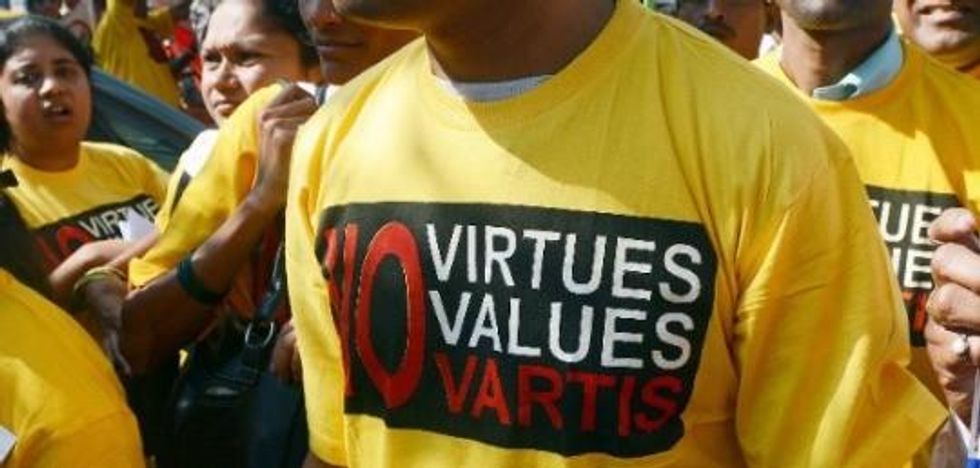

An Indian court just granted a huge victory to the sick all over the planet.

"People in developing countries worldwide will continue to have access to low-cost copycat versions of drugs for diseases like H.I.V. and cancer, at least for a while," said the front-page lead story in the New York Times on Tuesday. "Production of the generic drugs in India, the world's biggest provider of cheap medicines, was ensured on Monday in a ruling by the Indian Supreme Court."

The specific case involved the Swiss pharmaceutical giant Novartis, which unsuccessfully argued that the tinkering it did with its anti-leukemia drug Glivec was worthy of a new patent. At stake was not just access to affordable medicine for leukemia patients but also the survival of the Indian generic industry--the world's leading manufacturer of low-cost medications.

In 1970, India amended its patent law to have patents awarded only for the processes to make medicines, not for the final products. The ramifications were global.

"India became the 'pharmacy of the world's poor' in 1970," the BBC states. "This allowed its many drug producers to create generic copies of medicines still patent-protected in other countries --at a fraction of the price charged by Western drug firms."

So, Indian generic drug companies played a huge role in combating the biggest scourge of our time.

"It was only when Indian firms began to make cheap copies of HIV drugs that it became possible more than a decade ago to contemplate the treatment of millions of people in impoverished countries of Africa, where the AIDS epidemic was at its worst," The Guardian writes.

All this seemed to be in jeopardy when in 2005, India's parliament, under Western pressure, amended the patent law to comply with World Trade Organization rules. A lot of observers, including me, were worried that this move would mark the death-knell for the availability of affordable drugs around the world. But the Indian judiciary has pleasantly surprised us.

Advocacy groups are delighted.

"This is a huge relief for the millions of patients and doctors in developing countries who depend on affordable medicines from India, and for treatment providers like MSF," Dr. Unni Karunakara, the head of the Nobel Peace Prize-winning Medecins Sans Frontieres (Doctors Without Borders), said. "The Supreme Court's decision now makes patents on the medicines that we desperately need less likely."

There are worrisome clouds on the horizon, however. The awful 2005 law that the Indian parliament passed tightened patents on drugs made after 1995, and the anti-leukemia drug in question was introduced by Novartis in 1993. The real test will come when cases are heard for drugs developed recently or in the future.

"The million-dollar question is what is going to happen for new drugs that have not yet come out," says Leena Menghaney of Doctors Without Borders.

At the same time, the U.S. pharmaceutical industry is lobbying fast and furious for trade agreements (such as the proposed TransPacific Partnership) to include the toughest patent protections possible.

But these are looming battles to be fought on another day. For now, millions of people have reason to rejoice.

Dear Common Dreams reader, The U.S. is on a fast track to authoritarianism like nothing I've ever seen. Meanwhile, corporate news outlets are utterly capitulating to Trump, twisting their coverage to avoid drawing his ire while lining up to stuff cash in his pockets. That's why I believe that Common Dreams is doing the best and most consequential reporting that we've ever done. Our small but mighty team is a progressive reporting powerhouse, covering the news every day that the corporate media never will. Our mission has always been simple: To inform. To inspire. And to ignite change for the common good. Now here's the key piece that I want all our readers to understand: None of this would be possible without your financial support. That's not just some fundraising cliche. It's the absolute and literal truth. We don't accept corporate advertising and never will. We don't have a paywall because we don't think people should be blocked from critical news based on their ability to pay. Everything we do is funded by the donations of readers like you. Will you donate now to help power the nonprofit, independent reporting of Common Dreams? Thank you for being a vital member of our community. Together, we can keep independent journalism alive when it’s needed most. - Craig Brown, Co-founder |

"People in developing countries worldwide will continue to have access to low-cost copycat versions of drugs for diseases like H.I.V. and cancer, at least for a while," said the front-page lead story in the New York Times on Tuesday. "Production of the generic drugs in India, the world's biggest provider of cheap medicines, was ensured on Monday in a ruling by the Indian Supreme Court."

The specific case involved the Swiss pharmaceutical giant Novartis, which unsuccessfully argued that the tinkering it did with its anti-leukemia drug Glivec was worthy of a new patent. At stake was not just access to affordable medicine for leukemia patients but also the survival of the Indian generic industry--the world's leading manufacturer of low-cost medications.

In 1970, India amended its patent law to have patents awarded only for the processes to make medicines, not for the final products. The ramifications were global.

"India became the 'pharmacy of the world's poor' in 1970," the BBC states. "This allowed its many drug producers to create generic copies of medicines still patent-protected in other countries --at a fraction of the price charged by Western drug firms."

So, Indian generic drug companies played a huge role in combating the biggest scourge of our time.

"It was only when Indian firms began to make cheap copies of HIV drugs that it became possible more than a decade ago to contemplate the treatment of millions of people in impoverished countries of Africa, where the AIDS epidemic was at its worst," The Guardian writes.

All this seemed to be in jeopardy when in 2005, India's parliament, under Western pressure, amended the patent law to comply with World Trade Organization rules. A lot of observers, including me, were worried that this move would mark the death-knell for the availability of affordable drugs around the world. But the Indian judiciary has pleasantly surprised us.

Advocacy groups are delighted.

"This is a huge relief for the millions of patients and doctors in developing countries who depend on affordable medicines from India, and for treatment providers like MSF," Dr. Unni Karunakara, the head of the Nobel Peace Prize-winning Medecins Sans Frontieres (Doctors Without Borders), said. "The Supreme Court's decision now makes patents on the medicines that we desperately need less likely."

There are worrisome clouds on the horizon, however. The awful 2005 law that the Indian parliament passed tightened patents on drugs made after 1995, and the anti-leukemia drug in question was introduced by Novartis in 1993. The real test will come when cases are heard for drugs developed recently or in the future.

"The million-dollar question is what is going to happen for new drugs that have not yet come out," says Leena Menghaney of Doctors Without Borders.

At the same time, the U.S. pharmaceutical industry is lobbying fast and furious for trade agreements (such as the proposed TransPacific Partnership) to include the toughest patent protections possible.

But these are looming battles to be fought on another day. For now, millions of people have reason to rejoice.

"People in developing countries worldwide will continue to have access to low-cost copycat versions of drugs for diseases like H.I.V. and cancer, at least for a while," said the front-page lead story in the New York Times on Tuesday. "Production of the generic drugs in India, the world's biggest provider of cheap medicines, was ensured on Monday in a ruling by the Indian Supreme Court."

The specific case involved the Swiss pharmaceutical giant Novartis, which unsuccessfully argued that the tinkering it did with its anti-leukemia drug Glivec was worthy of a new patent. At stake was not just access to affordable medicine for leukemia patients but also the survival of the Indian generic industry--the world's leading manufacturer of low-cost medications.

In 1970, India amended its patent law to have patents awarded only for the processes to make medicines, not for the final products. The ramifications were global.

"India became the 'pharmacy of the world's poor' in 1970," the BBC states. "This allowed its many drug producers to create generic copies of medicines still patent-protected in other countries --at a fraction of the price charged by Western drug firms."

So, Indian generic drug companies played a huge role in combating the biggest scourge of our time.

"It was only when Indian firms began to make cheap copies of HIV drugs that it became possible more than a decade ago to contemplate the treatment of millions of people in impoverished countries of Africa, where the AIDS epidemic was at its worst," The Guardian writes.

All this seemed to be in jeopardy when in 2005, India's parliament, under Western pressure, amended the patent law to comply with World Trade Organization rules. A lot of observers, including me, were worried that this move would mark the death-knell for the availability of affordable drugs around the world. But the Indian judiciary has pleasantly surprised us.

Advocacy groups are delighted.

"This is a huge relief for the millions of patients and doctors in developing countries who depend on affordable medicines from India, and for treatment providers like MSF," Dr. Unni Karunakara, the head of the Nobel Peace Prize-winning Medecins Sans Frontieres (Doctors Without Borders), said. "The Supreme Court's decision now makes patents on the medicines that we desperately need less likely."

There are worrisome clouds on the horizon, however. The awful 2005 law that the Indian parliament passed tightened patents on drugs made after 1995, and the anti-leukemia drug in question was introduced by Novartis in 1993. The real test will come when cases are heard for drugs developed recently or in the future.

"The million-dollar question is what is going to happen for new drugs that have not yet come out," says Leena Menghaney of Doctors Without Borders.

At the same time, the U.S. pharmaceutical industry is lobbying fast and furious for trade agreements (such as the proposed TransPacific Partnership) to include the toughest patent protections possible.

But these are looming battles to be fought on another day. For now, millions of people have reason to rejoice.