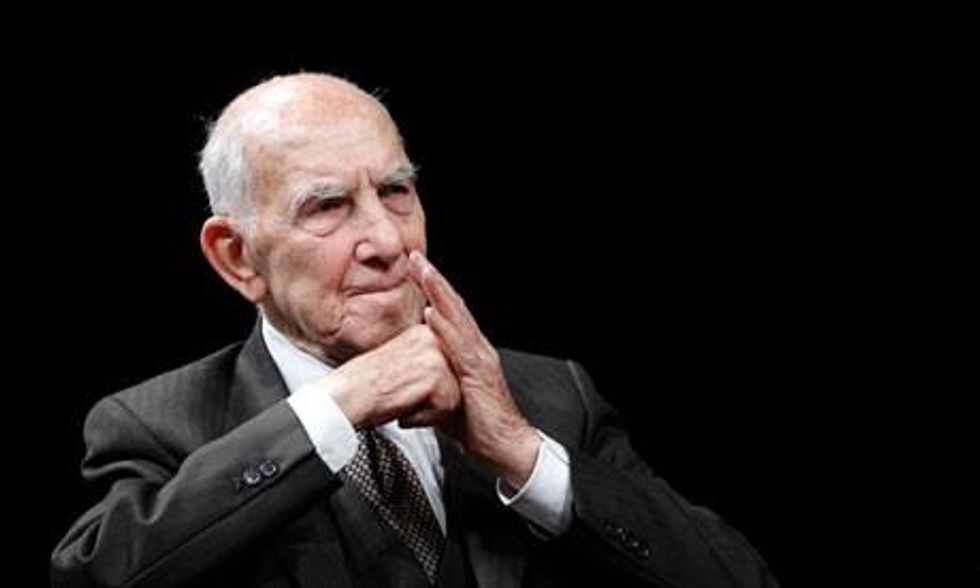

"I hope France gives him a state funeral," said the waiter from my local cafe upon hearing the news. Stephane Hessel, who died in Paris on Tuesday night, is the kind of man who inspires such awe.

Hessel certainly led an extraordinary life. Born German in 1917 Berlin, the son of Proust's first German translator, Hessel arrived in Paris at the age of seven. He graduated in philosophy from the prestigious Ecole Normale, and received French citizenship for his 20th birthday, in 1937. Four years later he joined General de Gaulle in London and enrolled in the French resistance. Arrested by the Gestapo in 1944 with 36 fellow resistants, he was sent to Buchenwald concentration camp, and was among six of them who miraculously survived. As the Paris-based Irish writer Fiachra Gibbons tweeted this morning: "Here is a man who symbolised the best of France, having survived the worst of it."As a member of the National Council of the Resistance, which was responsible for reshaping a new postwar France, he embarked on a career in diplomacy at the UN, where he took part in the drafting of the universal declaration of human rights. In the 1950s, he worked for Pierre Mendes France - who remains, to this day, a moral reference for the French left. Hessel was sent to Saigon, then to Algiers. Throughout the 70s and 80s he was an adviser to many ministers on international development and co-operation.

He was also the author of several essays on political commitment and involvement, but it is in 2010 that his political writing attracted tremendous international attention with his pamphlet Indignez-vous! (translated as Time for Outrage! in English). The book has sold more than 4m copies in 34 different languages.

A few weeks after the book's release in Spain, the civil disobedience movement the Indignados - a direct reference to Hessel's pamphlet - sprang to life and occupied a central Madrid square. The movement soon spread from Madrid to Sydney, from Jerusalem to New York. In September 2011, Occupy Wall Street launched more global initiatives, with protests organised in almost 1,000 cities and 82 countries. Hessel's call for public outrage at social injustice was finally heard on a universal scale.

In a 2006 interview with the French newspaper Liberation, in reply to the question, "What is the most important advice you were ever given?", Hessel said: "My mother once said to me, 'You must promise to be happy, it is the greatest favour you can do to others'. It has guided me throughout my life." And to the question, "What are you losing?" Hessel replied: "I'm lucky. I haven't lost the most important things in life: I remember all the faces I have met and all the poems I have learnt. I know 100 poems in different languages by heart and I recite them to myself. I keep learning new ones. Last week, I learnt Rilke's Sonnets to Orpheus."

Cinephiles have always had a particular fondness for him too. Hessel's mother was the inspiration for Catherine in Jules et Jim, a semi-autobiographical story by Henri-Pierre Roche which was adapted for the screen by Francois Truffaut in 1962. Hessel's mother, Helen, was in love with two men who happened to be best friends. One French, one German. "I thought, as a child, that the best thing for me to do, living among this amorous trio, was to become everyone's favourite," said Hessel. Why should the Franco-German trio quarrel and fight? They decided to live together, through the upheavals of history.

Europe has lost a great European - and France a much-loved child, poet and, above all, a combatant for justice and freedom.