Occupiers Arrive in Court Over a Year After Their Boston Encampment Was Raided

A common cause for grievance among some older activists of the sixties variety is that "the kids these days" don't protest. They're too apathetic and jaded. They're too isolated and detached from community.

A common cause for grievance among some older activists of the sixties variety is that "the kids these days" don't protest. They're too apathetic and jaded. They're too isolated and detached from community. And while that may be true in certain cases, the kids these days are also aware of the omnipresent police state that constantly hovers just above their crowns, waiting to strike down with the wrath of God if they stray even slightly past the boundaries of acceptable dissent.

That reminder sometimes comes in spectacular displays like in Oakland when police nearly killed veteran Scott Olson with a projectile during a October 2011 Occupy Oakland protest, or the violent November 15 raid of Zuccotti in Manhattan when police barred press from entering the park to witness their tactics.

More often, the reminder is a slow bureaucratic suffocation when arrested protesters languish in the legal system for months at a time--sometimes years and years--awaiting their time in court. This process is too dull for most media outlets to devote resources too, and most protesters can't afford the time and legal fees necessary to remain stuck in limbo.

Protesters needn't be stuck in jail during this glacial-speed process in order for it to be an impediment in their daily lives. Even being "free," but being required to return to court for hearing dates over and over is a highly disruptive factor in people's lives. Court dates mean taking time off from work or finding transportation to court. It means the state can call upon them whenever, and they have to drop everything, or else.

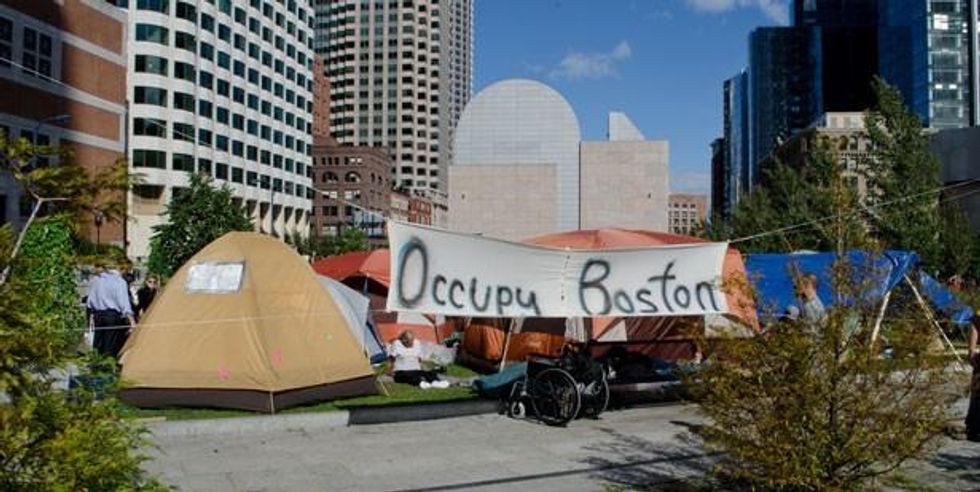

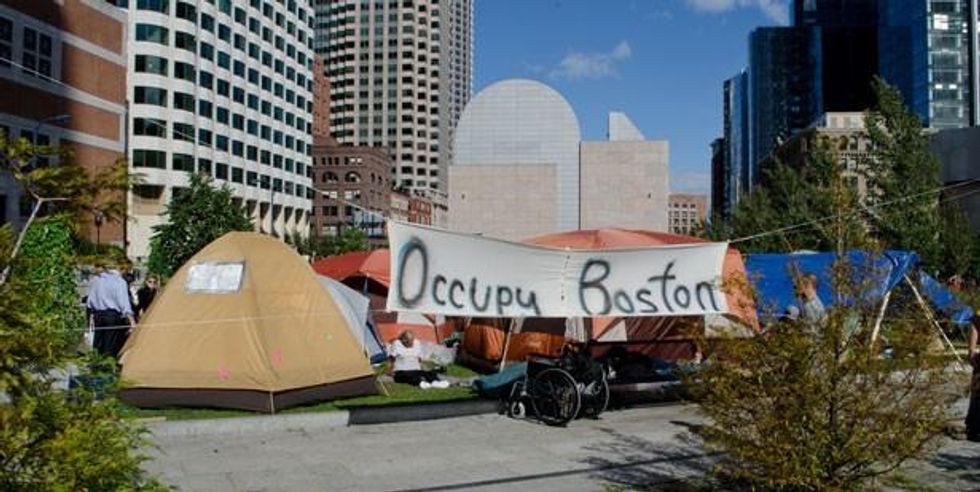

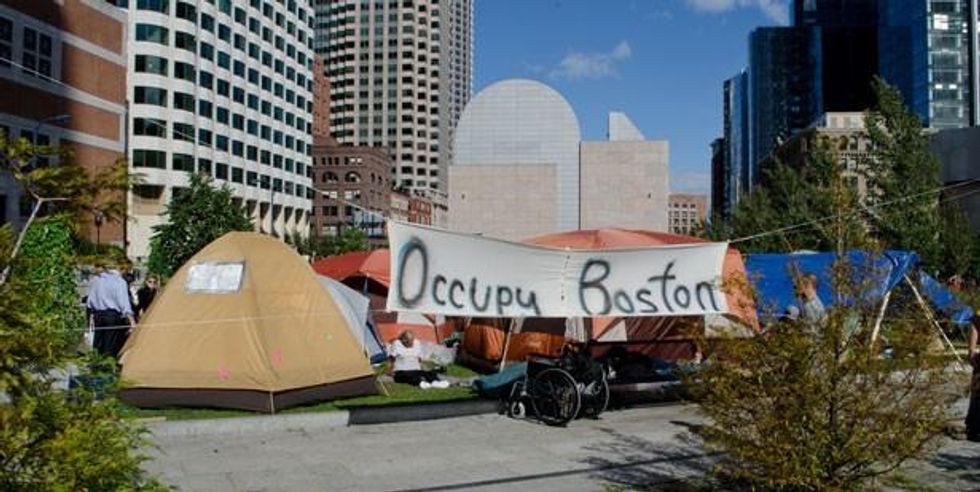

Five Occupy Boston defendants appeared in Boston Municipal Court on Monday--finally--following their arrests over a year ago (fourteen months, to be exact) after an October 2011 raid on the Occupy Boston encampment in Dewey Square. They were among 140 protesters charged with trespassing and unlawful assembly. (Only five defendents from the October raid have a date, the rest don't even know the co-defendents. Meanwhile, defendents from the final December 2011 raid haven't even had a court date set up yet).

Andrea Hill, Ashley Brewer, Brianne Milder, Tammi Arford and Kerry McDonald claim their constitutional rights of assembly and free speech were violated during the eviction.

"Arresting them and charging them with criminal conduct for exercising those rights was plainly unlawful and in violation of their constitutional rights to assembly and free speech under the First Amendment," stated a Friday press release from the National Lawyers Guild, the association from which attorneys have volunteered to represent the protesters.

If the judge in the case grants a dismissal, there won't be a trial, but if the judge denies the motion to dismiss, the protesters go to trail, which means more time surrendered to the state.

The agonizingly slow court system becomes all the more apparently absurd when one considers the level of "crime" in most Occupy cases: "trespassing and unlawful assembly," in the case of Occupy Boston, on land that conservancy documents say was designed to be a space for the people to assemble. The First Amendment means nothing when the state simply throws up a thousand barriers (e.g., permit requirements, public-private partnerships that slowly strip the "public" from "public space") preventing protesters from actually assembling and speaking freely.

Boston's Commonwealth offered the protesters a deal after their arrests: all trespassing charges would be turned to civil infractions and a $50 fee would be issued--another indication that protesters weren't really a threat to begin with. Dangerous criminals aren't freed after being charged $50 fines. Most protesters took that deal, understandably given the deeply unpleasant experience of being arrested in the first place and then slowly processed.

However, twenty-four people refused to take the deal, claiming that their rights were violated, and they wanted to go to court and present their case in front of a judge.

Theoretically, that's how the legal system is supposed to work. The Sixth Amendment to the US Constitution sets forth rights related to criminal prosecutions, including the right to a speedy trial. "Speedy" is an ambiguous term, but in Barker v. Wingo (1972) the Supreme Court laid down a four-part case-by-case balancing test to determine what "speedy" actually means, and the court determined a delay of a year or more from the date on which the speedy trial right "attaches"--meaning the date of arrest or indictment, whichever occurs first--is "presumptively prejudicial."

Meaning, you don't just have the right to a trial, you have the right for it not to be a slow-ass trial. The court has found clever ways to circumvent that, including not counting "the trial" as the process leading up to said trial, which is usually longer than the process of the trial itself. There's also the police tactic of "detaining" people without charging them with anything, a shady method that some protesters can escape by simply asking officers, "Am I free to go?" and then walking away if the officer replies in the affirmative. But often the police can snatch up protesters for any made-up reason, up to and including blocking foot traffic, a seriously laughable "crime" for anyone familiar with Manhattan sidewalks. Then those protesters are at the mercy of the slow courts.

It's worth remembering that the Occupy Boston Five have been awaiting their day in court for over a year, and yet the perpetrators of the crimes protested by these activists--meaning major Wall Street firms--haven't had to suffer the inefficiencies of the courts. No CEO has been showing up for court dates over the past year, having to reschedule his meetings and pick-up times for his kids. No CEO faces any charges for their very real crimes.

Truly, we have a very weird, inverted "justice" system.

An Urgent Message From Our Co-Founder

Dear Common Dreams reader, The U.S. is on a fast track to authoritarianism like nothing I've ever seen. Meanwhile, corporate news outlets are utterly capitulating to Trump, twisting their coverage to avoid drawing his ire while lining up to stuff cash in his pockets. That's why I believe that Common Dreams is doing the best and most consequential reporting that we've ever done. Our small but mighty team is a progressive reporting powerhouse, covering the news every day that the corporate media never will. Our mission has always been simple: To inform. To inspire. And to ignite change for the common good. Now here's the key piece that I want all our readers to understand: None of this would be possible without your financial support. That's not just some fundraising cliche. It's the absolute and literal truth. We don't accept corporate advertising and never will. We don't have a paywall because we don't think people should be blocked from critical news based on their ability to pay. Everything we do is funded by the donations of readers like you. Will you donate now to help power the nonprofit, independent reporting of Common Dreams? Thank you for being a vital member of our community. Together, we can keep independent journalism alive when it’s needed most. - Craig Brown, Co-founder |

A common cause for grievance among some older activists of the sixties variety is that "the kids these days" don't protest. They're too apathetic and jaded. They're too isolated and detached from community. And while that may be true in certain cases, the kids these days are also aware of the omnipresent police state that constantly hovers just above their crowns, waiting to strike down with the wrath of God if they stray even slightly past the boundaries of acceptable dissent.

That reminder sometimes comes in spectacular displays like in Oakland when police nearly killed veteran Scott Olson with a projectile during a October 2011 Occupy Oakland protest, or the violent November 15 raid of Zuccotti in Manhattan when police barred press from entering the park to witness their tactics.

More often, the reminder is a slow bureaucratic suffocation when arrested protesters languish in the legal system for months at a time--sometimes years and years--awaiting their time in court. This process is too dull for most media outlets to devote resources too, and most protesters can't afford the time and legal fees necessary to remain stuck in limbo.

Protesters needn't be stuck in jail during this glacial-speed process in order for it to be an impediment in their daily lives. Even being "free," but being required to return to court for hearing dates over and over is a highly disruptive factor in people's lives. Court dates mean taking time off from work or finding transportation to court. It means the state can call upon them whenever, and they have to drop everything, or else.

Five Occupy Boston defendants appeared in Boston Municipal Court on Monday--finally--following their arrests over a year ago (fourteen months, to be exact) after an October 2011 raid on the Occupy Boston encampment in Dewey Square. They were among 140 protesters charged with trespassing and unlawful assembly. (Only five defendents from the October raid have a date, the rest don't even know the co-defendents. Meanwhile, defendents from the final December 2011 raid haven't even had a court date set up yet).

Andrea Hill, Ashley Brewer, Brianne Milder, Tammi Arford and Kerry McDonald claim their constitutional rights of assembly and free speech were violated during the eviction.

"Arresting them and charging them with criminal conduct for exercising those rights was plainly unlawful and in violation of their constitutional rights to assembly and free speech under the First Amendment," stated a Friday press release from the National Lawyers Guild, the association from which attorneys have volunteered to represent the protesters.

If the judge in the case grants a dismissal, there won't be a trial, but if the judge denies the motion to dismiss, the protesters go to trail, which means more time surrendered to the state.

The agonizingly slow court system becomes all the more apparently absurd when one considers the level of "crime" in most Occupy cases: "trespassing and unlawful assembly," in the case of Occupy Boston, on land that conservancy documents say was designed to be a space for the people to assemble. The First Amendment means nothing when the state simply throws up a thousand barriers (e.g., permit requirements, public-private partnerships that slowly strip the "public" from "public space") preventing protesters from actually assembling and speaking freely.

Boston's Commonwealth offered the protesters a deal after their arrests: all trespassing charges would be turned to civil infractions and a $50 fee would be issued--another indication that protesters weren't really a threat to begin with. Dangerous criminals aren't freed after being charged $50 fines. Most protesters took that deal, understandably given the deeply unpleasant experience of being arrested in the first place and then slowly processed.

However, twenty-four people refused to take the deal, claiming that their rights were violated, and they wanted to go to court and present their case in front of a judge.

Theoretically, that's how the legal system is supposed to work. The Sixth Amendment to the US Constitution sets forth rights related to criminal prosecutions, including the right to a speedy trial. "Speedy" is an ambiguous term, but in Barker v. Wingo (1972) the Supreme Court laid down a four-part case-by-case balancing test to determine what "speedy" actually means, and the court determined a delay of a year or more from the date on which the speedy trial right "attaches"--meaning the date of arrest or indictment, whichever occurs first--is "presumptively prejudicial."

Meaning, you don't just have the right to a trial, you have the right for it not to be a slow-ass trial. The court has found clever ways to circumvent that, including not counting "the trial" as the process leading up to said trial, which is usually longer than the process of the trial itself. There's also the police tactic of "detaining" people without charging them with anything, a shady method that some protesters can escape by simply asking officers, "Am I free to go?" and then walking away if the officer replies in the affirmative. But often the police can snatch up protesters for any made-up reason, up to and including blocking foot traffic, a seriously laughable "crime" for anyone familiar with Manhattan sidewalks. Then those protesters are at the mercy of the slow courts.

It's worth remembering that the Occupy Boston Five have been awaiting their day in court for over a year, and yet the perpetrators of the crimes protested by these activists--meaning major Wall Street firms--haven't had to suffer the inefficiencies of the courts. No CEO has been showing up for court dates over the past year, having to reschedule his meetings and pick-up times for his kids. No CEO faces any charges for their very real crimes.

Truly, we have a very weird, inverted "justice" system.

A common cause for grievance among some older activists of the sixties variety is that "the kids these days" don't protest. They're too apathetic and jaded. They're too isolated and detached from community. And while that may be true in certain cases, the kids these days are also aware of the omnipresent police state that constantly hovers just above their crowns, waiting to strike down with the wrath of God if they stray even slightly past the boundaries of acceptable dissent.

That reminder sometimes comes in spectacular displays like in Oakland when police nearly killed veteran Scott Olson with a projectile during a October 2011 Occupy Oakland protest, or the violent November 15 raid of Zuccotti in Manhattan when police barred press from entering the park to witness their tactics.

More often, the reminder is a slow bureaucratic suffocation when arrested protesters languish in the legal system for months at a time--sometimes years and years--awaiting their time in court. This process is too dull for most media outlets to devote resources too, and most protesters can't afford the time and legal fees necessary to remain stuck in limbo.

Protesters needn't be stuck in jail during this glacial-speed process in order for it to be an impediment in their daily lives. Even being "free," but being required to return to court for hearing dates over and over is a highly disruptive factor in people's lives. Court dates mean taking time off from work or finding transportation to court. It means the state can call upon them whenever, and they have to drop everything, or else.

Five Occupy Boston defendants appeared in Boston Municipal Court on Monday--finally--following their arrests over a year ago (fourteen months, to be exact) after an October 2011 raid on the Occupy Boston encampment in Dewey Square. They were among 140 protesters charged with trespassing and unlawful assembly. (Only five defendents from the October raid have a date, the rest don't even know the co-defendents. Meanwhile, defendents from the final December 2011 raid haven't even had a court date set up yet).

Andrea Hill, Ashley Brewer, Brianne Milder, Tammi Arford and Kerry McDonald claim their constitutional rights of assembly and free speech were violated during the eviction.

"Arresting them and charging them with criminal conduct for exercising those rights was plainly unlawful and in violation of their constitutional rights to assembly and free speech under the First Amendment," stated a Friday press release from the National Lawyers Guild, the association from which attorneys have volunteered to represent the protesters.

If the judge in the case grants a dismissal, there won't be a trial, but if the judge denies the motion to dismiss, the protesters go to trail, which means more time surrendered to the state.

The agonizingly slow court system becomes all the more apparently absurd when one considers the level of "crime" in most Occupy cases: "trespassing and unlawful assembly," in the case of Occupy Boston, on land that conservancy documents say was designed to be a space for the people to assemble. The First Amendment means nothing when the state simply throws up a thousand barriers (e.g., permit requirements, public-private partnerships that slowly strip the "public" from "public space") preventing protesters from actually assembling and speaking freely.

Boston's Commonwealth offered the protesters a deal after their arrests: all trespassing charges would be turned to civil infractions and a $50 fee would be issued--another indication that protesters weren't really a threat to begin with. Dangerous criminals aren't freed after being charged $50 fines. Most protesters took that deal, understandably given the deeply unpleasant experience of being arrested in the first place and then slowly processed.

However, twenty-four people refused to take the deal, claiming that their rights were violated, and they wanted to go to court and present their case in front of a judge.

Theoretically, that's how the legal system is supposed to work. The Sixth Amendment to the US Constitution sets forth rights related to criminal prosecutions, including the right to a speedy trial. "Speedy" is an ambiguous term, but in Barker v. Wingo (1972) the Supreme Court laid down a four-part case-by-case balancing test to determine what "speedy" actually means, and the court determined a delay of a year or more from the date on which the speedy trial right "attaches"--meaning the date of arrest or indictment, whichever occurs first--is "presumptively prejudicial."

Meaning, you don't just have the right to a trial, you have the right for it not to be a slow-ass trial. The court has found clever ways to circumvent that, including not counting "the trial" as the process leading up to said trial, which is usually longer than the process of the trial itself. There's also the police tactic of "detaining" people without charging them with anything, a shady method that some protesters can escape by simply asking officers, "Am I free to go?" and then walking away if the officer replies in the affirmative. But often the police can snatch up protesters for any made-up reason, up to and including blocking foot traffic, a seriously laughable "crime" for anyone familiar with Manhattan sidewalks. Then those protesters are at the mercy of the slow courts.

It's worth remembering that the Occupy Boston Five have been awaiting their day in court for over a year, and yet the perpetrators of the crimes protested by these activists--meaning major Wall Street firms--haven't had to suffer the inefficiencies of the courts. No CEO has been showing up for court dates over the past year, having to reschedule his meetings and pick-up times for his kids. No CEO faces any charges for their very real crimes.

Truly, we have a very weird, inverted "justice" system.