As the fourth anniversary of Obama's pledge to close Guantanamo approaches, the pressure is on: it's been far too long, and the moment is now. But why is Guantanamo so hard to close?

Because it's been an integral part of American politics and policy for over a century. To understand what it takes to close Guantanamo, we should look to how we've failed - and succeeded - in closing it before.

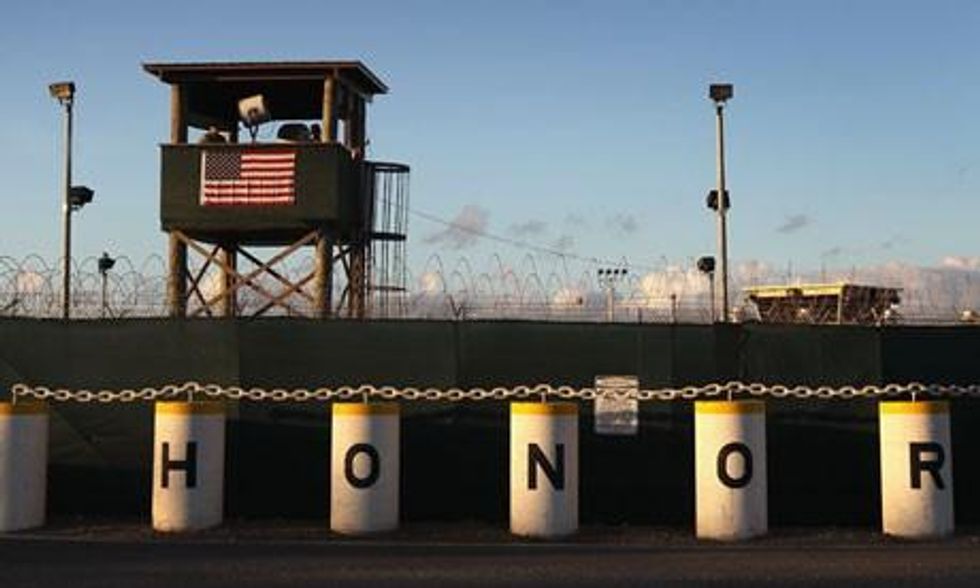

Gitmo's "legal black hole" opened in 1903 with a peculiar lease that affirmed Cuba's total sovereignty over Guantanamo Bay, but gave the US "complete jurisdiction and control". This inadvertently created a space where neither nation's laws clearly applied: a purgatory that's been used to park people whose legal rights posed political threats. Gitmo's generations of detainees have been inextricable, if often invisible, parts of America's deepest conflicts: over immigration, public health, human rights, and national security.

In 1991, thousands fled Haiti on makeshift boats, seeking political asylum in the US. Determined to rescue refugees from certain death at sea, but unwilling to accept so many, Bush I ordered the US coast guard to take over 20,000 to Gitmo. Most were returned to Haiti. But about 200 got caught in the middle: approved for asylum, but barred from the US for being HIV-positive. These refugees staged protests and harnessed international media attention. Concerned citizens lined US streets calling to close Guantanamo; Harold Koh (then at Yale Law) organized a legal battle.

In June 1993, a US district court judge ordered the camps closed. Public attention faded, overlooking that while the ruling released the individuals, it upheld the policy, allowing Gitmo to be used for indefinite detention.

Just a year later, President Clinton opened Guantanamo again, when a flotilla of over 30,000 Cuban rafters set to sea for Florida. Existing policy granted Cubans asylum; but the political threat the numbers posed prompted Clinton to order the coast guard to park the Cubans at Gitmo while he renegotiated the law: 30,000 Cubans languished in tent cities behind barbed wire for up to two years. In January of 1996, the last Cuban refugee left Gitmo.

"We must remember that the camps of Guantanamo are closing," noted refugee journalist Mario Pedro Graveran, "but ... Guantanamo Bay is a painful story that's not over yet."

In 1999, the doors opened again. Committed to helping victims of the Balkan conflict, President Clinton proposed shipping 20,000 Kosovar refugees to Gitmo, where he could offer a "safe haven" without offering asylum. This time, enough people remembered. Activists reminded a forgetful public what the "safe haven" looked like for Haitians and Cubans. After press conferences and protests, the refugees were brought to the US.

Gitmo again fell off the public radar. Three years later, Camp X-Ray, a detention facility built in 1994 for refugees, was repurposed for the first "enemy combatants".

But Guantanamo is much more than a prison: it's made up of the thousands of people who worked there, grew up there, and served there, whose stories reveal the many things Gitmo is and can be. Refugees remember Gitmo as both a site of confinement and a step to freedom; Cuban workers and American ex-pats remember it as both a place of exile and a treasured home. These stories inform what Guantanamo is - and what it means to close it.

Last month, a national dialogue began on what to remember about Guantanamo and why. The Guantanamo Public Memory Project involves historians, archivists, activists, military personnel, and over a dozen universities in raising public awareness of Gitmo's long history and foster dialogue on the future of this place, its people, and its policies. This fall, students from Pensacola to Phoenix collected stories of people who worked, grew up, served, were held, or advocated at Guantanamo to develop a digital timeline, interactive map, and physical exhibit, just opened in New York and traveling around the country.

Each exhibit panel poses a question students struggled with, such as: should the US judge the quality of the refugees it admits, and on what basis? Should Gitmo be returned to Cuba? The exhibit invites ongoing debate on these and other questions through events around the country, blogging, and digital voting.

"Remembering" means sustaining public engagement in Guantanamo. And sustaining exchange across political divides on issues Gitmo has shaped in our own communities, like immigration, national security, or Aids.

"Closing Guantanamo" isn't what it sounds like - even if Obama were to be successful, Gitmo will be with us for years to come. The lease with Cuba is perpetual. Today, even as 166 men remain detained, the base is readying itself for its next opening. Facilities to house 25,000 potential refugees were recently completed.

Our responsibility is to remember Guantanamo: to learn from its past, listen to the stories of all of its people, and always keep it in our sights.