SUBSCRIBE TO OUR FREE NEWSLETTER

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

5

#000000

#FFFFFF

To donate by check, phone, or other method, see our More Ways to Give page.

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

As two critical bills waited quietly on California Governor Jerry Brown's desk last weekend, immigrants across the state held their breath, hoping that the progressive legislation could affect the national immirgation debate.

As two critical bills waited quietly on California Governor Jerry Brown's desk last weekend, immigrants across the state held their breath, hoping that the progressive legislation could affect the national immirgation debate. By Sunday night, the anticipation gave way to disillusionment with two stunning vetoes.

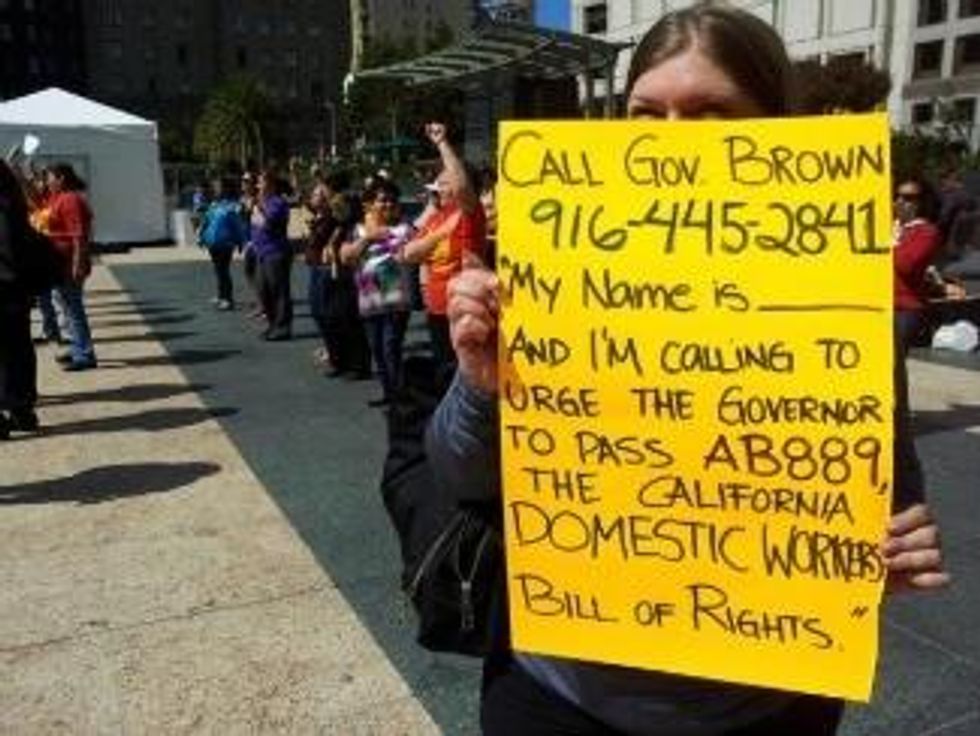

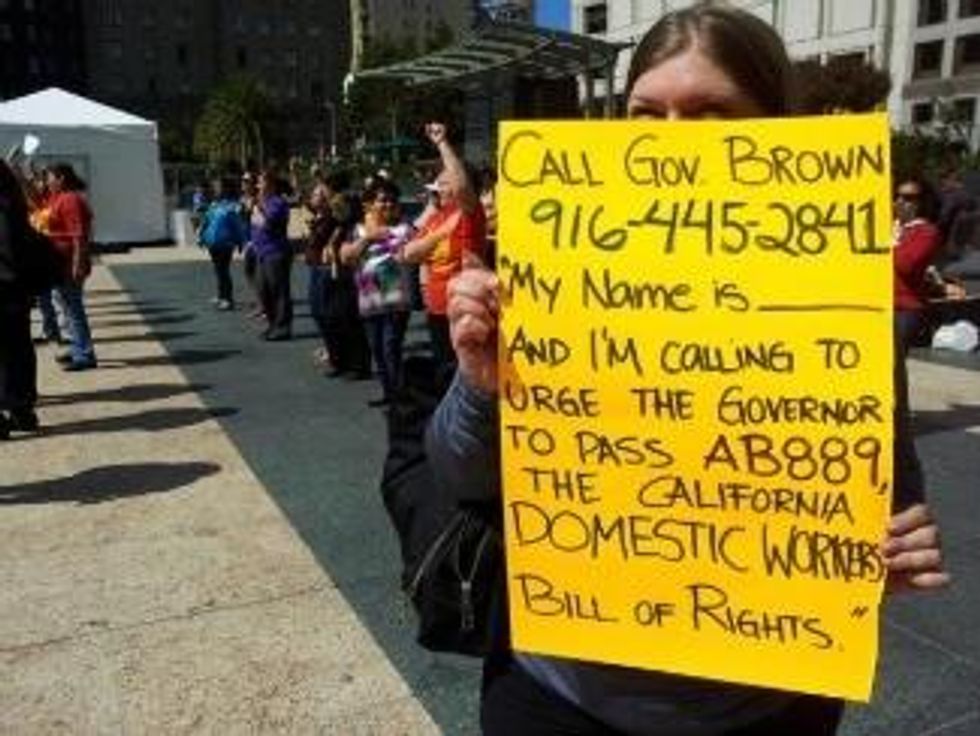

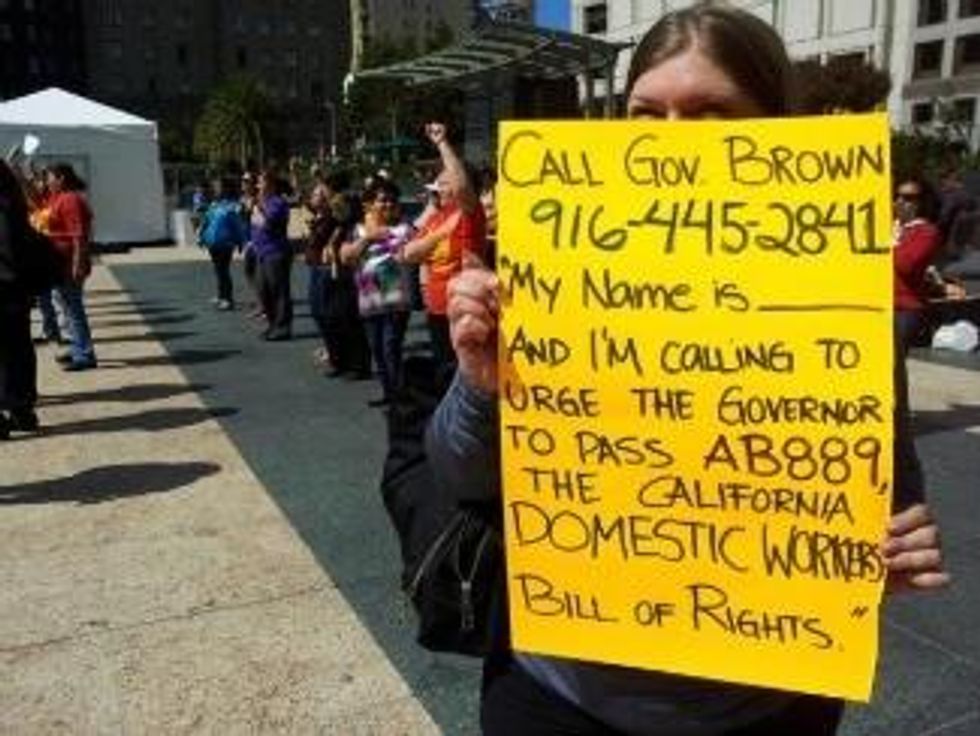

The highly anticipated Domestic Workers Bill of Rights would have enacted major protections for tens of thousands of housekeepers, nannies and other caregivers and closed loopholes ignored by federal labor law. It would have extended California's policies for overtime pay and workers' compensation, and helped ease in-house workers' arduous, sometimes-abusive work routines by providing for a set amount of sleep and the ability to cook one's own food.

Above all, the Bill of Rights would place California alongside New York (where similar legislation has already passed) in formally recognizing the rights and unique needs of this burgeoning, cross-cutting sector. The bill won support from a huge array of groups, from labor unions to celebrities, precisely because of the myriad social issues that domestic work braids together: the changing demographics of the workforce, the challenges of securing affordable childcare or elder care for families, and the struggles of immigrant workers, particularly women of color, in a largely unregulated industry.

But Brown scrapped the bill (sadly following an earlier veto by former Gov. Arnold Schwarzenegger) and aligned himself with the business lobby, led by the California Chamber of Commerce, which had complained that the provisions of the bill would be unworkable and overly burdensome for employers.

The California Domestic Workers Coalition will continue its campaign (with plans to deploy sponge bombs to help Brown "clean up his act") by building on its growing network of allies, including women's rights, labor and faith groups. Looking ahead, Katie Joaquin, a Filipino community activist with the California Domestic Workers Coalition, tells Working In These Times, "We're going to continue to build upon those relationships. And the first step is to hold Governor Brown accountable for what we view as a blatant lack of leadership."

Inspired by the New York example, Joaquin says, the California bill is part of a movement for what the National Domestic Workers Alliance calls "an alternative vision of care," which is based on sustainable working conditions and better training in the care industries, in order to meet the growing need for caregivers as the population ages. "We need to have a vision for training and caring for caregivers at the same time that we're making care accessible for families," Joaquin says.

Immigration policy complicates the labor struggle. Brown delivered a one-two punch to California's migrant communities by also vetoing the Trust Act, which would have restrained the power of local police to route arrestees suspected of immigration violations into the custody of Immigrations and Customs Enforcement (ICE). That means that the mass deportation of undocumented immigrants, including domestic caregivers and other low-wage workers, will continue.

Immigrant rights activists had pushed the Trust Act to counter the Obama administration's enforcement regime, particularly the Secure Communities program, which encourages federal and local police to collaborate to nab undocumented immigrants. The program mirrors Arizona's infamous SB1070 law and other state initiatives that threaten to expand racial profiling of Latinos and feed the federal deportation machine (which hasn't significantly eased up in spite of the administration's slippery claims of refraining from deportating "low priority" cases, such as students with clean records).

Still, aside from the painful vetoes, Brown managed to approve more modest pro-immigrant measures, such as allowing driver's licenses for some undocumented immigrants (a move apparently aimed at the youth who would qualify for temporary immigration relief and work permits under the White House's new "deferred action" policy).

The problem is that making it easier for undocumented workers to drive isn't going to prevent them from being pulled over and ensnared in deportation proceedings. A young man named Juan Santiago told the Associated Press:

he was pleased he would be able to get from his home in Madera to his college classes 30 miles away once his work permit application is approved. But he said the measure does little for his mother, who brought him across the Arizona desert into the U.S. when he was 11.

"It was a happy and a sad day for us," Santiago said. "The fact that the governor vetoed the TRUST Act, it means there's nothing to protect the rest of my family members."

The legislative changes that immigrants most need now are those that protect the whole neighborhood--at work, in school and at home. In an email to Working In These Times, Chris Newman, legal director of California-based National Day Laborer Organizing Network (NDLON), one of the leading advocates for the Trust Act, says:

Equality demands that all Californians have faith in law enforcement, and the vetoes send a message that whether it's civil rights, labor rights, or public safety, Jerry Brown does not respect the interests of immigrant workers in California.

While the vetoes were a blow to the movement, passing pro-immigrant policies is not an end in itself. Even in New York, where a hard-fought Domestic Workers Bill of Rights is already on the books, workers have faced difficulty in using the law to directly challenge employers over workplace violations.

Building political savvy and leverage on the street level is critical, with or without supportive legislation. As NDLON activist Pablo Alvarado wrote on the group's blog, the governor "can veto a bill but he cannot veto a movement." Ultimately, it's the community's power, not the letter of the law, that defines justice.

Dear Common Dreams reader, The U.S. is on a fast track to authoritarianism like nothing I've ever seen. Meanwhile, corporate news outlets are utterly capitulating to Trump, twisting their coverage to avoid drawing his ire while lining up to stuff cash in his pockets. That's why I believe that Common Dreams is doing the best and most consequential reporting that we've ever done. Our small but mighty team is a progressive reporting powerhouse, covering the news every day that the corporate media never will. Our mission has always been simple: To inform. To inspire. And to ignite change for the common good. Now here's the key piece that I want all our readers to understand: None of this would be possible without your financial support. That's not just some fundraising cliche. It's the absolute and literal truth. We don't accept corporate advertising and never will. We don't have a paywall because we don't think people should be blocked from critical news based on their ability to pay. Everything we do is funded by the donations of readers like you. Will you donate now to help power the nonprofit, independent reporting of Common Dreams? Thank you for being a vital member of our community. Together, we can keep independent journalism alive when it’s needed most. - Craig Brown, Co-founder |

As two critical bills waited quietly on California Governor Jerry Brown's desk last weekend, immigrants across the state held their breath, hoping that the progressive legislation could affect the national immirgation debate. By Sunday night, the anticipation gave way to disillusionment with two stunning vetoes.

The highly anticipated Domestic Workers Bill of Rights would have enacted major protections for tens of thousands of housekeepers, nannies and other caregivers and closed loopholes ignored by federal labor law. It would have extended California's policies for overtime pay and workers' compensation, and helped ease in-house workers' arduous, sometimes-abusive work routines by providing for a set amount of sleep and the ability to cook one's own food.

Above all, the Bill of Rights would place California alongside New York (where similar legislation has already passed) in formally recognizing the rights and unique needs of this burgeoning, cross-cutting sector. The bill won support from a huge array of groups, from labor unions to celebrities, precisely because of the myriad social issues that domestic work braids together: the changing demographics of the workforce, the challenges of securing affordable childcare or elder care for families, and the struggles of immigrant workers, particularly women of color, in a largely unregulated industry.

But Brown scrapped the bill (sadly following an earlier veto by former Gov. Arnold Schwarzenegger) and aligned himself with the business lobby, led by the California Chamber of Commerce, which had complained that the provisions of the bill would be unworkable and overly burdensome for employers.

The California Domestic Workers Coalition will continue its campaign (with plans to deploy sponge bombs to help Brown "clean up his act") by building on its growing network of allies, including women's rights, labor and faith groups. Looking ahead, Katie Joaquin, a Filipino community activist with the California Domestic Workers Coalition, tells Working In These Times, "We're going to continue to build upon those relationships. And the first step is to hold Governor Brown accountable for what we view as a blatant lack of leadership."

Inspired by the New York example, Joaquin says, the California bill is part of a movement for what the National Domestic Workers Alliance calls "an alternative vision of care," which is based on sustainable working conditions and better training in the care industries, in order to meet the growing need for caregivers as the population ages. "We need to have a vision for training and caring for caregivers at the same time that we're making care accessible for families," Joaquin says.

Immigration policy complicates the labor struggle. Brown delivered a one-two punch to California's migrant communities by also vetoing the Trust Act, which would have restrained the power of local police to route arrestees suspected of immigration violations into the custody of Immigrations and Customs Enforcement (ICE). That means that the mass deportation of undocumented immigrants, including domestic caregivers and other low-wage workers, will continue.

Immigrant rights activists had pushed the Trust Act to counter the Obama administration's enforcement regime, particularly the Secure Communities program, which encourages federal and local police to collaborate to nab undocumented immigrants. The program mirrors Arizona's infamous SB1070 law and other state initiatives that threaten to expand racial profiling of Latinos and feed the federal deportation machine (which hasn't significantly eased up in spite of the administration's slippery claims of refraining from deportating "low priority" cases, such as students with clean records).

Still, aside from the painful vetoes, Brown managed to approve more modest pro-immigrant measures, such as allowing driver's licenses for some undocumented immigrants (a move apparently aimed at the youth who would qualify for temporary immigration relief and work permits under the White House's new "deferred action" policy).

The problem is that making it easier for undocumented workers to drive isn't going to prevent them from being pulled over and ensnared in deportation proceedings. A young man named Juan Santiago told the Associated Press:

he was pleased he would be able to get from his home in Madera to his college classes 30 miles away once his work permit application is approved. But he said the measure does little for his mother, who brought him across the Arizona desert into the U.S. when he was 11.

"It was a happy and a sad day for us," Santiago said. "The fact that the governor vetoed the TRUST Act, it means there's nothing to protect the rest of my family members."

The legislative changes that immigrants most need now are those that protect the whole neighborhood--at work, in school and at home. In an email to Working In These Times, Chris Newman, legal director of California-based National Day Laborer Organizing Network (NDLON), one of the leading advocates for the Trust Act, says:

Equality demands that all Californians have faith in law enforcement, and the vetoes send a message that whether it's civil rights, labor rights, or public safety, Jerry Brown does not respect the interests of immigrant workers in California.

While the vetoes were a blow to the movement, passing pro-immigrant policies is not an end in itself. Even in New York, where a hard-fought Domestic Workers Bill of Rights is already on the books, workers have faced difficulty in using the law to directly challenge employers over workplace violations.

Building political savvy and leverage on the street level is critical, with or without supportive legislation. As NDLON activist Pablo Alvarado wrote on the group's blog, the governor "can veto a bill but he cannot veto a movement." Ultimately, it's the community's power, not the letter of the law, that defines justice.

As two critical bills waited quietly on California Governor Jerry Brown's desk last weekend, immigrants across the state held their breath, hoping that the progressive legislation could affect the national immirgation debate. By Sunday night, the anticipation gave way to disillusionment with two stunning vetoes.

The highly anticipated Domestic Workers Bill of Rights would have enacted major protections for tens of thousands of housekeepers, nannies and other caregivers and closed loopholes ignored by federal labor law. It would have extended California's policies for overtime pay and workers' compensation, and helped ease in-house workers' arduous, sometimes-abusive work routines by providing for a set amount of sleep and the ability to cook one's own food.

Above all, the Bill of Rights would place California alongside New York (where similar legislation has already passed) in formally recognizing the rights and unique needs of this burgeoning, cross-cutting sector. The bill won support from a huge array of groups, from labor unions to celebrities, precisely because of the myriad social issues that domestic work braids together: the changing demographics of the workforce, the challenges of securing affordable childcare or elder care for families, and the struggles of immigrant workers, particularly women of color, in a largely unregulated industry.

But Brown scrapped the bill (sadly following an earlier veto by former Gov. Arnold Schwarzenegger) and aligned himself with the business lobby, led by the California Chamber of Commerce, which had complained that the provisions of the bill would be unworkable and overly burdensome for employers.

The California Domestic Workers Coalition will continue its campaign (with plans to deploy sponge bombs to help Brown "clean up his act") by building on its growing network of allies, including women's rights, labor and faith groups. Looking ahead, Katie Joaquin, a Filipino community activist with the California Domestic Workers Coalition, tells Working In These Times, "We're going to continue to build upon those relationships. And the first step is to hold Governor Brown accountable for what we view as a blatant lack of leadership."

Inspired by the New York example, Joaquin says, the California bill is part of a movement for what the National Domestic Workers Alliance calls "an alternative vision of care," which is based on sustainable working conditions and better training in the care industries, in order to meet the growing need for caregivers as the population ages. "We need to have a vision for training and caring for caregivers at the same time that we're making care accessible for families," Joaquin says.

Immigration policy complicates the labor struggle. Brown delivered a one-two punch to California's migrant communities by also vetoing the Trust Act, which would have restrained the power of local police to route arrestees suspected of immigration violations into the custody of Immigrations and Customs Enforcement (ICE). That means that the mass deportation of undocumented immigrants, including domestic caregivers and other low-wage workers, will continue.

Immigrant rights activists had pushed the Trust Act to counter the Obama administration's enforcement regime, particularly the Secure Communities program, which encourages federal and local police to collaborate to nab undocumented immigrants. The program mirrors Arizona's infamous SB1070 law and other state initiatives that threaten to expand racial profiling of Latinos and feed the federal deportation machine (which hasn't significantly eased up in spite of the administration's slippery claims of refraining from deportating "low priority" cases, such as students with clean records).

Still, aside from the painful vetoes, Brown managed to approve more modest pro-immigrant measures, such as allowing driver's licenses for some undocumented immigrants (a move apparently aimed at the youth who would qualify for temporary immigration relief and work permits under the White House's new "deferred action" policy).

The problem is that making it easier for undocumented workers to drive isn't going to prevent them from being pulled over and ensnared in deportation proceedings. A young man named Juan Santiago told the Associated Press:

he was pleased he would be able to get from his home in Madera to his college classes 30 miles away once his work permit application is approved. But he said the measure does little for his mother, who brought him across the Arizona desert into the U.S. when he was 11.

"It was a happy and a sad day for us," Santiago said. "The fact that the governor vetoed the TRUST Act, it means there's nothing to protect the rest of my family members."

The legislative changes that immigrants most need now are those that protect the whole neighborhood--at work, in school and at home. In an email to Working In These Times, Chris Newman, legal director of California-based National Day Laborer Organizing Network (NDLON), one of the leading advocates for the Trust Act, says:

Equality demands that all Californians have faith in law enforcement, and the vetoes send a message that whether it's civil rights, labor rights, or public safety, Jerry Brown does not respect the interests of immigrant workers in California.

While the vetoes were a blow to the movement, passing pro-immigrant policies is not an end in itself. Even in New York, where a hard-fought Domestic Workers Bill of Rights is already on the books, workers have faced difficulty in using the law to directly challenge employers over workplace violations.

Building political savvy and leverage on the street level is critical, with or without supportive legislation. As NDLON activist Pablo Alvarado wrote on the group's blog, the governor "can veto a bill but he cannot veto a movement." Ultimately, it's the community's power, not the letter of the law, that defines justice.