SUBSCRIBE TO OUR FREE NEWSLETTER

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

5

#000000

#FFFFFF

To donate by check, phone, or other method, see our More Ways to Give page.

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

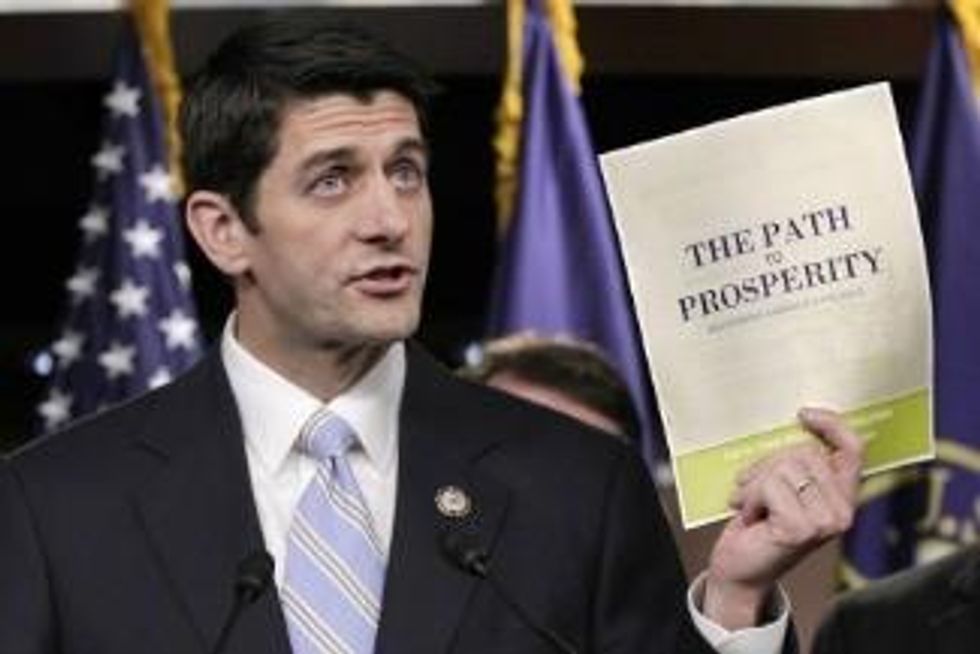

Mitt Romney has picked Paul Ryan, the seven-term Wisconsin congressman, born during the first Nixon administration, and not old enough to have voted for either Ronald Reagan or the first Bush. It is a puzzling choice, more calculated than inspiring, more cautious than bold, and in some respects, just as strategically faulty as John McCain's pick of Sarah Palin.

Mitt Romney has picked Paul Ryan, the seven-term Wisconsin congressman, born during the first Nixon administration, and not old enough to have voted for either Ronald Reagan or the first Bush. It is a puzzling choice, more calculated than inspiring, more cautious than bold, and in some respects, just as strategically faulty as John McCain's pick of Sarah Palin.

In Ryan, Romney found the only congressional Republican who's produced the semblance of an alternative to Obama's economic and health care plans. But he's also found a mirror of himself. No one will accuse Ryan of being compassionate, generous, warm or particularly caring, qualities Romney lacks, and needs, if he's going to make inroads with women and middle class voters who so far mistrust him. Ryan is friendlier than Romney, but friendliness to colleagues and reporters isn't the same thing as connecting with voters beyond Wisconsin (where he has been successful enough to win six of his seven elections with more than 60 percent of the vote).

Still, Ryan doesn't guarantee Romney Wisconsin, a battleground state with 10 electoral votes that's nevertheless not crucial to either candidate's path to victory. The states most in play are Ohio, Florida and Pennsylvania, where Ryan's appointment doesn't look like a vote-singer: in Ohio and Pennsylvania, his tax-cutting and war on anti-poverty programs will be more alienating than attractive. In Florida, he's a gift to the Obama campaign, which now only has to lay out the Ryan plan for Medicare to turn even a few tea party drinkers into latter-day Obama disciples.

Most of all, the Ryan nomination at first appears to be the anti-Palin nomination: Romney did not want to risk handing hysterics to the media. He's succeeded, though whether Ryan knows more than Palin about Russia is still to be determined. Unlike Palin, Ryan is well spoken. Unlike Palin, he's nowhere near rabid. Where Palin projected an aggressive sort of anti-intellectual populism, Ryan projects brain power. He's not reality-show material. He reads. But the media focus of the Romney-Ryan ticket will be on Ryan's economic plan, which--in another puzzle of this nomination--happens to upstage Romney's own, which has so far been virtually non-existent except in vague, nostalgic outlines for Reagan-era rhetoric. In that sense, Romney is making the same mistake McCain did: he's picked someone who will take the focus away from him. Ryan will do so quite differently from Palin. But he can still be more of a distractive liability than a centering force: Romney needed a jolt, an earthy, believable, sympathetic running mate who can help overcome Obama's likability. He's not getting that in Paul Ryan.

Ryan's backstory is compelling enough: Irish stock, hard-working Midwestern family, dad dying early (Ryan found him dead in his bed one morning), grandmother dying of Alzheimer's (Ryan cared for her), but soon after college it was all career politics, starting with an internship in the office of former Wisconsin Sen. Bob Kasten, then writing speeches for Jack Kemp, who was Bob Dole's running mate in the forgotten race of 1996, then his run for the House in 1997. In 2004, he was George W. Bush's point man on Social Security privatization.

Ironically, Ryan went to college thanks to his widowed mother's Social Security survivor's benefits. The privatization scheme was one of the big disasters of the second Bush term, though it had the benefit of being lost among many, many other disasters, shielding Ryan from embarrassment. Had Social Security been even partly privatized by then, would have wiped out whatever savings millions of retirees might have been depending on, forcing the government to make up enormous losses. The alternative was the existing system: Social Security is the only large government program running a surplus, without which the government would not as easily have financed its operations, since it has been freely borrowing from the Social Security trust fund since the 1990s. One point should not be lost: Ryan's judgment about his plans viability was very poor. He appears not to have learned much from it: "The Administration did a bad job of selling it," is how he still explains it (as he did to The New Yorker).

Yet Ryan's strength, we are told, is in his ideas. He does have a few--a rarity in his party these days, where the word "no" tends to be the sum total of all philosophies. "If you're going to criticize, then you should propose," Ryan told the New Yorker's Ryan Lizza. So while it's true that conservative think tanks, politicians and columnists have seized on Ryan's budget plan with feverish enthusiasm, it's not necessarily because of the brilliance if the plan. It's because it's the only alternative Republicans have managed. It shines by default in a universe of dark matter.

Ryan would cut more than $5 trillion from the budget over 10 years. Medicaid, Medicare and food stamps would be eliminated as we now know them, and replaced with more limited block-grant type, or voucher, programs, as opposed to entitlements. (It's why Paul Krugman calls the Ryan plan "a fraud" and "a piece of mean-spirited junk.")

Ryan would also eliminate six income tax brackets and replace them with just two. He would cut the top tax rate of 35 percent (itself reduced from the Clinton-era rate of just over 39 percent) to 25 percent, with the bottom bracket's rate set at 10 percent. The corporate tax rate would be cut from 35 percent to 25 percent. To pay for it all, Ryan says he would eliminate loopholes and tax breaks. But he's refused to spell out the loopholes and tax breaks he would eliminate to make up the enormous loss in revenue. Two of those tax breaks, for example, bear eliminating, and would, in fact, save hundreds of billions of dollars: the mortgage-interest deduction (about $80 billion a year) and the tax credit afforded employee-provided health care (about $230 billion). But Ryan is not about to float those proposals in the middle of an election. And there are no other major proposals that would generate savings of that size.

Ryan's plan offers alternatives. But they're not original alternatives. And they're not coherent, if by coherence one expects numbers to add up. They're a combination of two previous presidents' ideas recast for what would be the third time as the way out of debt. It hasn't worked before. There's no reason to think it would work now.

Supply-side economics--thee notion that cutting taxes would spur growth enough to generate more tax revenue--was first tried by Ronald Reagan. It very quickly turned the United States from a creditor nation into a debtor nation. Reagan just as quickly racked up more deficits in his two terms than all previous presidents combined. But that's the Ryan program: cut taxes.

Ryan's health care alternative isn't original, either. He would scrap Obama's reforms, including three of its centerpieces: the prohibition against insurers' booting off an individual who becomes too sick and the prohibition against insurers using pre-existing conditions to keep an individual from getting health care. He would eliminate the insurance mandate, requiring that every American carry insurance. He would instead provide a tax credit to people buying insurance. That was the plan John McCain proposed when he ran for president four years ago: a $5,000 tax credit to every individual buying insurance. Such a credit, of course, would not cover more than the most bare-bones insurance plan.

The third pillar of Ryan's fiscal conservatism is his overhaul of Medicare. It's not quite an overhaul, which suggests reforming a system to make it better. It's privatization. He would turn Medicare into a voucher program. The first version of that proposal provoked such an uproar that Ryan retreated and reworked it, so that the existing Medicare system would not be entirely eliminated. He would keep it as an option. But it would be a very costly option--if that's what beneficiaries chose to hold on to. In other words, he would make it difficult for all but the richest beneficiaries to stick with it. That's not the sort of plan that gives elderly Floridians their second wind.

Ryan's intellectual north pole is Ayn Rand's Atlas Shrugged, a cinderblock of a book that showcases Rand's ability to write English as if it were a hammer-throw competition (and to remind us why Rand is the Sarah Palin translation of Nietzsche). It's fabulous reading in adolescence. It's a little worrisome when grown-ups don't see beyond it. "The reason I got involved in public service, by and large, if I had to credit one thinker, one person, it would be Ayn Rand," he told the Atlas Society named for Rand. "The fight we are in here, make no mistake about it, is a fight of individualism versus collectivism."

Rand was a devout atheist. Ryan is a devout Catholic, though he's not made friends among prominent Catholics: "We would be remiss in our duty to you and our students," a letter to Ryan signed by the Georgetown University faculty read, "if we did not challenge your continuing misuse of Catholic teaching to defend a budget plan that decimates food programs for struggling families, radically weakens protections for the elderly and sick, and gives more tax breaks to the wealthiest few. As the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops has wisely noted in several letters to Congress - 'a just framework for future budgets cannot rely on disproportionate cuts in essential services to poor persons.' Catholic bishops recently wrote that 'the House-passed budget resolution fails to meet these moral criteria.' In short, your budget appears to reflect the values of your favorite philosopher, Ayn Rand, rather than the Gospel of Jesus Christ. Her call to selfishness and her antagonism toward religion are antithetical to the Gospel values of compassion and love."

Who is John Galt? For Mitt Romney, it's Paul Ryan, the alliterative not to an "RR" ticket (think Ronald Reagan), with Rand as a permanent sub-R. But there's a cautionary tale in Ryan's Rand worship, not quite hinted at in the book itself, where nothing is a hint when it can be better spelled out with a sledge-hammer: "But far in the distance, on the edge of the earth, a small flame was waving in the wind. It seemed to be calling and waiting for the words of John Galt was now to pronounce. 'The road is cleared,' said Galt. 'We are going back to the world.' He raised his hand--and over the desolate earth, he traced in space the sign of the dollar."

Also sprach Paul Ryan.

Dear Common Dreams reader, The U.S. is on a fast track to authoritarianism like nothing I've ever seen. Meanwhile, corporate news outlets are utterly capitulating to Trump, twisting their coverage to avoid drawing his ire while lining up to stuff cash in his pockets. That's why I believe that Common Dreams is doing the best and most consequential reporting that we've ever done. Our small but mighty team is a progressive reporting powerhouse, covering the news every day that the corporate media never will. Our mission has always been simple: To inform. To inspire. And to ignite change for the common good. Now here's the key piece that I want all our readers to understand: None of this would be possible without your financial support. That's not just some fundraising cliche. It's the absolute and literal truth. We don't accept corporate advertising and never will. We don't have a paywall because we don't think people should be blocked from critical news based on their ability to pay. Everything we do is funded by the donations of readers like you. Will you donate now to help power the nonprofit, independent reporting of Common Dreams? Thank you for being a vital member of our community. Together, we can keep independent journalism alive when it’s needed most. - Craig Brown, Co-founder |

Mitt Romney has picked Paul Ryan, the seven-term Wisconsin congressman, born during the first Nixon administration, and not old enough to have voted for either Ronald Reagan or the first Bush. It is a puzzling choice, more calculated than inspiring, more cautious than bold, and in some respects, just as strategically faulty as John McCain's pick of Sarah Palin.

In Ryan, Romney found the only congressional Republican who's produced the semblance of an alternative to Obama's economic and health care plans. But he's also found a mirror of himself. No one will accuse Ryan of being compassionate, generous, warm or particularly caring, qualities Romney lacks, and needs, if he's going to make inroads with women and middle class voters who so far mistrust him. Ryan is friendlier than Romney, but friendliness to colleagues and reporters isn't the same thing as connecting with voters beyond Wisconsin (where he has been successful enough to win six of his seven elections with more than 60 percent of the vote).

Still, Ryan doesn't guarantee Romney Wisconsin, a battleground state with 10 electoral votes that's nevertheless not crucial to either candidate's path to victory. The states most in play are Ohio, Florida and Pennsylvania, where Ryan's appointment doesn't look like a vote-singer: in Ohio and Pennsylvania, his tax-cutting and war on anti-poverty programs will be more alienating than attractive. In Florida, he's a gift to the Obama campaign, which now only has to lay out the Ryan plan for Medicare to turn even a few tea party drinkers into latter-day Obama disciples.

Most of all, the Ryan nomination at first appears to be the anti-Palin nomination: Romney did not want to risk handing hysterics to the media. He's succeeded, though whether Ryan knows more than Palin about Russia is still to be determined. Unlike Palin, Ryan is well spoken. Unlike Palin, he's nowhere near rabid. Where Palin projected an aggressive sort of anti-intellectual populism, Ryan projects brain power. He's not reality-show material. He reads. But the media focus of the Romney-Ryan ticket will be on Ryan's economic plan, which--in another puzzle of this nomination--happens to upstage Romney's own, which has so far been virtually non-existent except in vague, nostalgic outlines for Reagan-era rhetoric. In that sense, Romney is making the same mistake McCain did: he's picked someone who will take the focus away from him. Ryan will do so quite differently from Palin. But he can still be more of a distractive liability than a centering force: Romney needed a jolt, an earthy, believable, sympathetic running mate who can help overcome Obama's likability. He's not getting that in Paul Ryan.

Ryan's backstory is compelling enough: Irish stock, hard-working Midwestern family, dad dying early (Ryan found him dead in his bed one morning), grandmother dying of Alzheimer's (Ryan cared for her), but soon after college it was all career politics, starting with an internship in the office of former Wisconsin Sen. Bob Kasten, then writing speeches for Jack Kemp, who was Bob Dole's running mate in the forgotten race of 1996, then his run for the House in 1997. In 2004, he was George W. Bush's point man on Social Security privatization.

Ironically, Ryan went to college thanks to his widowed mother's Social Security survivor's benefits. The privatization scheme was one of the big disasters of the second Bush term, though it had the benefit of being lost among many, many other disasters, shielding Ryan from embarrassment. Had Social Security been even partly privatized by then, would have wiped out whatever savings millions of retirees might have been depending on, forcing the government to make up enormous losses. The alternative was the existing system: Social Security is the only large government program running a surplus, without which the government would not as easily have financed its operations, since it has been freely borrowing from the Social Security trust fund since the 1990s. One point should not be lost: Ryan's judgment about his plans viability was very poor. He appears not to have learned much from it: "The Administration did a bad job of selling it," is how he still explains it (as he did to The New Yorker).

Yet Ryan's strength, we are told, is in his ideas. He does have a few--a rarity in his party these days, where the word "no" tends to be the sum total of all philosophies. "If you're going to criticize, then you should propose," Ryan told the New Yorker's Ryan Lizza. So while it's true that conservative think tanks, politicians and columnists have seized on Ryan's budget plan with feverish enthusiasm, it's not necessarily because of the brilliance if the plan. It's because it's the only alternative Republicans have managed. It shines by default in a universe of dark matter.

Ryan would cut more than $5 trillion from the budget over 10 years. Medicaid, Medicare and food stamps would be eliminated as we now know them, and replaced with more limited block-grant type, or voucher, programs, as opposed to entitlements. (It's why Paul Krugman calls the Ryan plan "a fraud" and "a piece of mean-spirited junk.")

Ryan would also eliminate six income tax brackets and replace them with just two. He would cut the top tax rate of 35 percent (itself reduced from the Clinton-era rate of just over 39 percent) to 25 percent, with the bottom bracket's rate set at 10 percent. The corporate tax rate would be cut from 35 percent to 25 percent. To pay for it all, Ryan says he would eliminate loopholes and tax breaks. But he's refused to spell out the loopholes and tax breaks he would eliminate to make up the enormous loss in revenue. Two of those tax breaks, for example, bear eliminating, and would, in fact, save hundreds of billions of dollars: the mortgage-interest deduction (about $80 billion a year) and the tax credit afforded employee-provided health care (about $230 billion). But Ryan is not about to float those proposals in the middle of an election. And there are no other major proposals that would generate savings of that size.

Ryan's plan offers alternatives. But they're not original alternatives. And they're not coherent, if by coherence one expects numbers to add up. They're a combination of two previous presidents' ideas recast for what would be the third time as the way out of debt. It hasn't worked before. There's no reason to think it would work now.

Supply-side economics--thee notion that cutting taxes would spur growth enough to generate more tax revenue--was first tried by Ronald Reagan. It very quickly turned the United States from a creditor nation into a debtor nation. Reagan just as quickly racked up more deficits in his two terms than all previous presidents combined. But that's the Ryan program: cut taxes.

Ryan's health care alternative isn't original, either. He would scrap Obama's reforms, including three of its centerpieces: the prohibition against insurers' booting off an individual who becomes too sick and the prohibition against insurers using pre-existing conditions to keep an individual from getting health care. He would eliminate the insurance mandate, requiring that every American carry insurance. He would instead provide a tax credit to people buying insurance. That was the plan John McCain proposed when he ran for president four years ago: a $5,000 tax credit to every individual buying insurance. Such a credit, of course, would not cover more than the most bare-bones insurance plan.

The third pillar of Ryan's fiscal conservatism is his overhaul of Medicare. It's not quite an overhaul, which suggests reforming a system to make it better. It's privatization. He would turn Medicare into a voucher program. The first version of that proposal provoked such an uproar that Ryan retreated and reworked it, so that the existing Medicare system would not be entirely eliminated. He would keep it as an option. But it would be a very costly option--if that's what beneficiaries chose to hold on to. In other words, he would make it difficult for all but the richest beneficiaries to stick with it. That's not the sort of plan that gives elderly Floridians their second wind.

Ryan's intellectual north pole is Ayn Rand's Atlas Shrugged, a cinderblock of a book that showcases Rand's ability to write English as if it were a hammer-throw competition (and to remind us why Rand is the Sarah Palin translation of Nietzsche). It's fabulous reading in adolescence. It's a little worrisome when grown-ups don't see beyond it. "The reason I got involved in public service, by and large, if I had to credit one thinker, one person, it would be Ayn Rand," he told the Atlas Society named for Rand. "The fight we are in here, make no mistake about it, is a fight of individualism versus collectivism."

Rand was a devout atheist. Ryan is a devout Catholic, though he's not made friends among prominent Catholics: "We would be remiss in our duty to you and our students," a letter to Ryan signed by the Georgetown University faculty read, "if we did not challenge your continuing misuse of Catholic teaching to defend a budget plan that decimates food programs for struggling families, radically weakens protections for the elderly and sick, and gives more tax breaks to the wealthiest few. As the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops has wisely noted in several letters to Congress - 'a just framework for future budgets cannot rely on disproportionate cuts in essential services to poor persons.' Catholic bishops recently wrote that 'the House-passed budget resolution fails to meet these moral criteria.' In short, your budget appears to reflect the values of your favorite philosopher, Ayn Rand, rather than the Gospel of Jesus Christ. Her call to selfishness and her antagonism toward religion are antithetical to the Gospel values of compassion and love."

Who is John Galt? For Mitt Romney, it's Paul Ryan, the alliterative not to an "RR" ticket (think Ronald Reagan), with Rand as a permanent sub-R. But there's a cautionary tale in Ryan's Rand worship, not quite hinted at in the book itself, where nothing is a hint when it can be better spelled out with a sledge-hammer: "But far in the distance, on the edge of the earth, a small flame was waving in the wind. It seemed to be calling and waiting for the words of John Galt was now to pronounce. 'The road is cleared,' said Galt. 'We are going back to the world.' He raised his hand--and over the desolate earth, he traced in space the sign of the dollar."

Also sprach Paul Ryan.

Mitt Romney has picked Paul Ryan, the seven-term Wisconsin congressman, born during the first Nixon administration, and not old enough to have voted for either Ronald Reagan or the first Bush. It is a puzzling choice, more calculated than inspiring, more cautious than bold, and in some respects, just as strategically faulty as John McCain's pick of Sarah Palin.

In Ryan, Romney found the only congressional Republican who's produced the semblance of an alternative to Obama's economic and health care plans. But he's also found a mirror of himself. No one will accuse Ryan of being compassionate, generous, warm or particularly caring, qualities Romney lacks, and needs, if he's going to make inroads with women and middle class voters who so far mistrust him. Ryan is friendlier than Romney, but friendliness to colleagues and reporters isn't the same thing as connecting with voters beyond Wisconsin (where he has been successful enough to win six of his seven elections with more than 60 percent of the vote).

Still, Ryan doesn't guarantee Romney Wisconsin, a battleground state with 10 electoral votes that's nevertheless not crucial to either candidate's path to victory. The states most in play are Ohio, Florida and Pennsylvania, where Ryan's appointment doesn't look like a vote-singer: in Ohio and Pennsylvania, his tax-cutting and war on anti-poverty programs will be more alienating than attractive. In Florida, he's a gift to the Obama campaign, which now only has to lay out the Ryan plan for Medicare to turn even a few tea party drinkers into latter-day Obama disciples.

Most of all, the Ryan nomination at first appears to be the anti-Palin nomination: Romney did not want to risk handing hysterics to the media. He's succeeded, though whether Ryan knows more than Palin about Russia is still to be determined. Unlike Palin, Ryan is well spoken. Unlike Palin, he's nowhere near rabid. Where Palin projected an aggressive sort of anti-intellectual populism, Ryan projects brain power. He's not reality-show material. He reads. But the media focus of the Romney-Ryan ticket will be on Ryan's economic plan, which--in another puzzle of this nomination--happens to upstage Romney's own, which has so far been virtually non-existent except in vague, nostalgic outlines for Reagan-era rhetoric. In that sense, Romney is making the same mistake McCain did: he's picked someone who will take the focus away from him. Ryan will do so quite differently from Palin. But he can still be more of a distractive liability than a centering force: Romney needed a jolt, an earthy, believable, sympathetic running mate who can help overcome Obama's likability. He's not getting that in Paul Ryan.

Ryan's backstory is compelling enough: Irish stock, hard-working Midwestern family, dad dying early (Ryan found him dead in his bed one morning), grandmother dying of Alzheimer's (Ryan cared for her), but soon after college it was all career politics, starting with an internship in the office of former Wisconsin Sen. Bob Kasten, then writing speeches for Jack Kemp, who was Bob Dole's running mate in the forgotten race of 1996, then his run for the House in 1997. In 2004, he was George W. Bush's point man on Social Security privatization.

Ironically, Ryan went to college thanks to his widowed mother's Social Security survivor's benefits. The privatization scheme was one of the big disasters of the second Bush term, though it had the benefit of being lost among many, many other disasters, shielding Ryan from embarrassment. Had Social Security been even partly privatized by then, would have wiped out whatever savings millions of retirees might have been depending on, forcing the government to make up enormous losses. The alternative was the existing system: Social Security is the only large government program running a surplus, without which the government would not as easily have financed its operations, since it has been freely borrowing from the Social Security trust fund since the 1990s. One point should not be lost: Ryan's judgment about his plans viability was very poor. He appears not to have learned much from it: "The Administration did a bad job of selling it," is how he still explains it (as he did to The New Yorker).

Yet Ryan's strength, we are told, is in his ideas. He does have a few--a rarity in his party these days, where the word "no" tends to be the sum total of all philosophies. "If you're going to criticize, then you should propose," Ryan told the New Yorker's Ryan Lizza. So while it's true that conservative think tanks, politicians and columnists have seized on Ryan's budget plan with feverish enthusiasm, it's not necessarily because of the brilliance if the plan. It's because it's the only alternative Republicans have managed. It shines by default in a universe of dark matter.

Ryan would cut more than $5 trillion from the budget over 10 years. Medicaid, Medicare and food stamps would be eliminated as we now know them, and replaced with more limited block-grant type, or voucher, programs, as opposed to entitlements. (It's why Paul Krugman calls the Ryan plan "a fraud" and "a piece of mean-spirited junk.")

Ryan would also eliminate six income tax brackets and replace them with just two. He would cut the top tax rate of 35 percent (itself reduced from the Clinton-era rate of just over 39 percent) to 25 percent, with the bottom bracket's rate set at 10 percent. The corporate tax rate would be cut from 35 percent to 25 percent. To pay for it all, Ryan says he would eliminate loopholes and tax breaks. But he's refused to spell out the loopholes and tax breaks he would eliminate to make up the enormous loss in revenue. Two of those tax breaks, for example, bear eliminating, and would, in fact, save hundreds of billions of dollars: the mortgage-interest deduction (about $80 billion a year) and the tax credit afforded employee-provided health care (about $230 billion). But Ryan is not about to float those proposals in the middle of an election. And there are no other major proposals that would generate savings of that size.

Ryan's plan offers alternatives. But they're not original alternatives. And they're not coherent, if by coherence one expects numbers to add up. They're a combination of two previous presidents' ideas recast for what would be the third time as the way out of debt. It hasn't worked before. There's no reason to think it would work now.

Supply-side economics--thee notion that cutting taxes would spur growth enough to generate more tax revenue--was first tried by Ronald Reagan. It very quickly turned the United States from a creditor nation into a debtor nation. Reagan just as quickly racked up more deficits in his two terms than all previous presidents combined. But that's the Ryan program: cut taxes.

Ryan's health care alternative isn't original, either. He would scrap Obama's reforms, including three of its centerpieces: the prohibition against insurers' booting off an individual who becomes too sick and the prohibition against insurers using pre-existing conditions to keep an individual from getting health care. He would eliminate the insurance mandate, requiring that every American carry insurance. He would instead provide a tax credit to people buying insurance. That was the plan John McCain proposed when he ran for president four years ago: a $5,000 tax credit to every individual buying insurance. Such a credit, of course, would not cover more than the most bare-bones insurance plan.

The third pillar of Ryan's fiscal conservatism is his overhaul of Medicare. It's not quite an overhaul, which suggests reforming a system to make it better. It's privatization. He would turn Medicare into a voucher program. The first version of that proposal provoked such an uproar that Ryan retreated and reworked it, so that the existing Medicare system would not be entirely eliminated. He would keep it as an option. But it would be a very costly option--if that's what beneficiaries chose to hold on to. In other words, he would make it difficult for all but the richest beneficiaries to stick with it. That's not the sort of plan that gives elderly Floridians their second wind.

Ryan's intellectual north pole is Ayn Rand's Atlas Shrugged, a cinderblock of a book that showcases Rand's ability to write English as if it were a hammer-throw competition (and to remind us why Rand is the Sarah Palin translation of Nietzsche). It's fabulous reading in adolescence. It's a little worrisome when grown-ups don't see beyond it. "The reason I got involved in public service, by and large, if I had to credit one thinker, one person, it would be Ayn Rand," he told the Atlas Society named for Rand. "The fight we are in here, make no mistake about it, is a fight of individualism versus collectivism."

Rand was a devout atheist. Ryan is a devout Catholic, though he's not made friends among prominent Catholics: "We would be remiss in our duty to you and our students," a letter to Ryan signed by the Georgetown University faculty read, "if we did not challenge your continuing misuse of Catholic teaching to defend a budget plan that decimates food programs for struggling families, radically weakens protections for the elderly and sick, and gives more tax breaks to the wealthiest few. As the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops has wisely noted in several letters to Congress - 'a just framework for future budgets cannot rely on disproportionate cuts in essential services to poor persons.' Catholic bishops recently wrote that 'the House-passed budget resolution fails to meet these moral criteria.' In short, your budget appears to reflect the values of your favorite philosopher, Ayn Rand, rather than the Gospel of Jesus Christ. Her call to selfishness and her antagonism toward religion are antithetical to the Gospel values of compassion and love."

Who is John Galt? For Mitt Romney, it's Paul Ryan, the alliterative not to an "RR" ticket (think Ronald Reagan), with Rand as a permanent sub-R. But there's a cautionary tale in Ryan's Rand worship, not quite hinted at in the book itself, where nothing is a hint when it can be better spelled out with a sledge-hammer: "But far in the distance, on the edge of the earth, a small flame was waving in the wind. It seemed to be calling and waiting for the words of John Galt was now to pronounce. 'The road is cleared,' said Galt. 'We are going back to the world.' He raised his hand--and over the desolate earth, he traced in space the sign of the dollar."

Also sprach Paul Ryan.