Time for 'Banksters' To Be Prosecuted

"Banksters," the cover of the Economist magazine charges, depicting a gaggle of bankers dressed as extras off the "Goodfellas" lot.

"Banksters," the cover of the Economist magazine charges, depicting a gaggle of bankers dressed as extras off the "Goodfellas" lot. The editors were reacting to Libor-gate, the collusion among traders of major banks to fix the London interbank offered lending rate, the most recent, most obscure and the most explosive revelation from what seems a bottomless pit of corruption in global banks.

Once more the big banks are exposed in systematic fraudulent activity. When Barclays agreed to a $450 million fine for trying to rig the Libor, its CEO offered the classic excuse: Everyone does it. Once more the question remains: Will CEOs and CFOs, as well as traders, be prosecuted? Or will they depart with their multimillion dollar rewards intact, leaving shareholders to pay the tab for the hundreds of millions in fines?

The Barclays settlement exposed that traders colluded to try to fix the Libor rate. This is the rate used as the basis for exotic derivatives as well as mortgages, credit card and personal loan rates. Almost everyone is affected. Fixing the rate even a few hundreds of a percentage point could make Barclays millions on any single day -- money taken out of the pockets of consumers and investors. Once more the banks were rigging the rules; once more their customers were their mark.

The stakes are staggering. The Libor should be as good as gold. It pegs the value of up to $800 trillion in financial instruments. The collusion was systematic and routine. Investigations are underway not only in the United Kingdom but also in the United States, Canada and the European Union. Those named in the probes are all the usual suspects: JPMorgan Chase, Citibank, UBS, Deutsche Bank, HSBC, UBS and others. This wasn't rogue trading, as the Economist concludes; it was more like a cartel.

The Economist writes that what has been revealed here is "the rotten heart of finance," a "culture of casual dishonesty." Once more the big banks are revealed to have allowed greed to trample any concern about trust, respect or legality.

As investment analyst David Kotok suggests, consider the implications of the Barclays settlement: The general counsel tells the bank's directors that the bank is offered a settlement for a half-billion dollars in fines, with the resignation of the chair of the board, the chief executive and the chief operating officer, with others to follow. The board, knowing the evidence, agrees to take that deal. Other banks are in line for the same level of culpability.

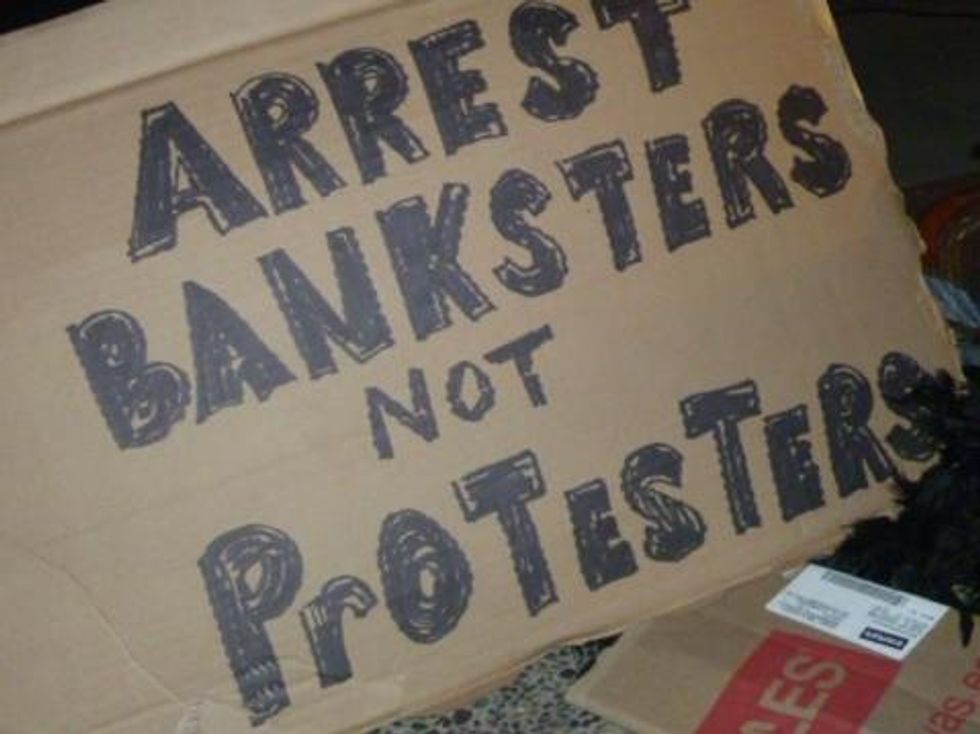

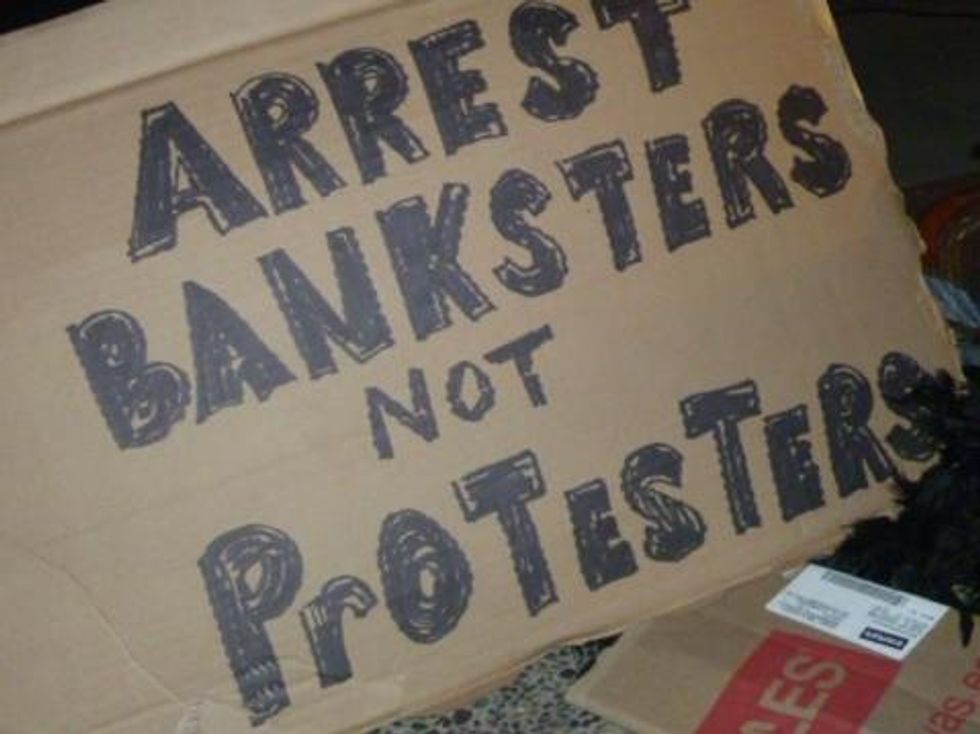

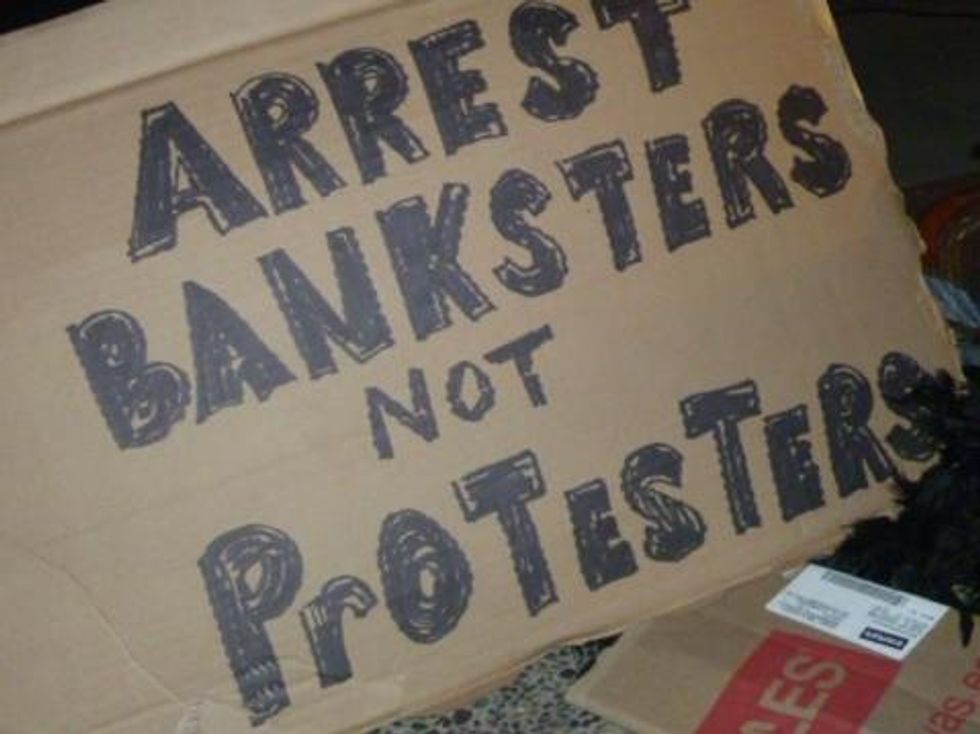

We are five years since Wall Street's excesses blew up the global economy, and the scandals just keep coming. Each scandal reinforces the need for tough regulation and tough enforcement. Each scandal proves over again the importance of breaking up the big banks. Each scandal raises the question of personal responsibility. How come borrowers are prosecuted for defrauding their banks, but bankers seem never to be prosecuted for defrauding their customers? George Osborne, the conservative British chancellor of the Exchequer, put it succinctly: "Fraud is a crime in ordinary business -- why shouldn't it be so in banking?" He is demanding action: "Punish wrongdoing. Right the wrong of the age of irresponsibility."

We haven't heard anything like that out of Washington. Libor-gate once more exposes how lax this administration has been on the banks -- and how irresponsible and, frankly, craven Republicans and Mitt Romney have been on this question. Romney echoes the know-nothing Republican right's call for repealing what little bank regulation has been passed since the financial collapse -- primarily the Dodd-Frank legislation. He touts deregulation in the wake of a global economic calamity caused in large part by the misguided belief that banks can police themselves.

Not surprisingly, Romney and Republicans are raking in donations from Wall Street. But they are catering to banksters that know no shame. For example, one of the most powerful Wall Street lobbying groups is the Securities Industry and Financial Markets Association, which has been leading the drive to weaken Dodd-Frank and exempt derivatives from transparency. Its chair was Jerry del Missier, the COO of Barclays, who lost his job and apparently his chairmanship in Libor-gate. Why are we not surprised?

Last January, Barclays' hard-edged CEO Robert E. Diamond Jr. announced that it was time for bankers to get their brass back. "There was a period of remorse and apology for banks," he declared. "I think that period is over." More and more of the customers defrauded by bankers might agree. They are tired of fake remorse and ritual apology. That period is over. It is time for prosecutions to begin.

An Urgent Message From Our Co-Founder

Dear Common Dreams reader, The U.S. is on a fast track to authoritarianism like nothing I've ever seen. Meanwhile, corporate news outlets are utterly capitulating to Trump, twisting their coverage to avoid drawing his ire while lining up to stuff cash in his pockets. That's why I believe that Common Dreams is doing the best and most consequential reporting that we've ever done. Our small but mighty team is a progressive reporting powerhouse, covering the news every day that the corporate media never will. Our mission has always been simple: To inform. To inspire. And to ignite change for the common good. Now here's the key piece that I want all our readers to understand: None of this would be possible without your financial support. That's not just some fundraising cliche. It's the absolute and literal truth. We don't accept corporate advertising and never will. We don't have a paywall because we don't think people should be blocked from critical news based on their ability to pay. Everything we do is funded by the donations of readers like you. Will you donate now to help power the nonprofit, independent reporting of Common Dreams? Thank you for being a vital member of our community. Together, we can keep independent journalism alive when it’s needed most. - Craig Brown, Co-founder |

"Banksters," the cover of the Economist magazine charges, depicting a gaggle of bankers dressed as extras off the "Goodfellas" lot. The editors were reacting to Libor-gate, the collusion among traders of major banks to fix the London interbank offered lending rate, the most recent, most obscure and the most explosive revelation from what seems a bottomless pit of corruption in global banks.

Once more the big banks are exposed in systematic fraudulent activity. When Barclays agreed to a $450 million fine for trying to rig the Libor, its CEO offered the classic excuse: Everyone does it. Once more the question remains: Will CEOs and CFOs, as well as traders, be prosecuted? Or will they depart with their multimillion dollar rewards intact, leaving shareholders to pay the tab for the hundreds of millions in fines?

The Barclays settlement exposed that traders colluded to try to fix the Libor rate. This is the rate used as the basis for exotic derivatives as well as mortgages, credit card and personal loan rates. Almost everyone is affected. Fixing the rate even a few hundreds of a percentage point could make Barclays millions on any single day -- money taken out of the pockets of consumers and investors. Once more the banks were rigging the rules; once more their customers were their mark.

The stakes are staggering. The Libor should be as good as gold. It pegs the value of up to $800 trillion in financial instruments. The collusion was systematic and routine. Investigations are underway not only in the United Kingdom but also in the United States, Canada and the European Union. Those named in the probes are all the usual suspects: JPMorgan Chase, Citibank, UBS, Deutsche Bank, HSBC, UBS and others. This wasn't rogue trading, as the Economist concludes; it was more like a cartel.

The Economist writes that what has been revealed here is "the rotten heart of finance," a "culture of casual dishonesty." Once more the big banks are revealed to have allowed greed to trample any concern about trust, respect or legality.

As investment analyst David Kotok suggests, consider the implications of the Barclays settlement: The general counsel tells the bank's directors that the bank is offered a settlement for a half-billion dollars in fines, with the resignation of the chair of the board, the chief executive and the chief operating officer, with others to follow. The board, knowing the evidence, agrees to take that deal. Other banks are in line for the same level of culpability.

We are five years since Wall Street's excesses blew up the global economy, and the scandals just keep coming. Each scandal reinforces the need for tough regulation and tough enforcement. Each scandal proves over again the importance of breaking up the big banks. Each scandal raises the question of personal responsibility. How come borrowers are prosecuted for defrauding their banks, but bankers seem never to be prosecuted for defrauding their customers? George Osborne, the conservative British chancellor of the Exchequer, put it succinctly: "Fraud is a crime in ordinary business -- why shouldn't it be so in banking?" He is demanding action: "Punish wrongdoing. Right the wrong of the age of irresponsibility."

We haven't heard anything like that out of Washington. Libor-gate once more exposes how lax this administration has been on the banks -- and how irresponsible and, frankly, craven Republicans and Mitt Romney have been on this question. Romney echoes the know-nothing Republican right's call for repealing what little bank regulation has been passed since the financial collapse -- primarily the Dodd-Frank legislation. He touts deregulation in the wake of a global economic calamity caused in large part by the misguided belief that banks can police themselves.

Not surprisingly, Romney and Republicans are raking in donations from Wall Street. But they are catering to banksters that know no shame. For example, one of the most powerful Wall Street lobbying groups is the Securities Industry and Financial Markets Association, which has been leading the drive to weaken Dodd-Frank and exempt derivatives from transparency. Its chair was Jerry del Missier, the COO of Barclays, who lost his job and apparently his chairmanship in Libor-gate. Why are we not surprised?

Last January, Barclays' hard-edged CEO Robert E. Diamond Jr. announced that it was time for bankers to get their brass back. "There was a period of remorse and apology for banks," he declared. "I think that period is over." More and more of the customers defrauded by bankers might agree. They are tired of fake remorse and ritual apology. That period is over. It is time for prosecutions to begin.

"Banksters," the cover of the Economist magazine charges, depicting a gaggle of bankers dressed as extras off the "Goodfellas" lot. The editors were reacting to Libor-gate, the collusion among traders of major banks to fix the London interbank offered lending rate, the most recent, most obscure and the most explosive revelation from what seems a bottomless pit of corruption in global banks.

Once more the big banks are exposed in systematic fraudulent activity. When Barclays agreed to a $450 million fine for trying to rig the Libor, its CEO offered the classic excuse: Everyone does it. Once more the question remains: Will CEOs and CFOs, as well as traders, be prosecuted? Or will they depart with their multimillion dollar rewards intact, leaving shareholders to pay the tab for the hundreds of millions in fines?

The Barclays settlement exposed that traders colluded to try to fix the Libor rate. This is the rate used as the basis for exotic derivatives as well as mortgages, credit card and personal loan rates. Almost everyone is affected. Fixing the rate even a few hundreds of a percentage point could make Barclays millions on any single day -- money taken out of the pockets of consumers and investors. Once more the banks were rigging the rules; once more their customers were their mark.

The stakes are staggering. The Libor should be as good as gold. It pegs the value of up to $800 trillion in financial instruments. The collusion was systematic and routine. Investigations are underway not only in the United Kingdom but also in the United States, Canada and the European Union. Those named in the probes are all the usual suspects: JPMorgan Chase, Citibank, UBS, Deutsche Bank, HSBC, UBS and others. This wasn't rogue trading, as the Economist concludes; it was more like a cartel.

The Economist writes that what has been revealed here is "the rotten heart of finance," a "culture of casual dishonesty." Once more the big banks are revealed to have allowed greed to trample any concern about trust, respect or legality.

As investment analyst David Kotok suggests, consider the implications of the Barclays settlement: The general counsel tells the bank's directors that the bank is offered a settlement for a half-billion dollars in fines, with the resignation of the chair of the board, the chief executive and the chief operating officer, with others to follow. The board, knowing the evidence, agrees to take that deal. Other banks are in line for the same level of culpability.

We are five years since Wall Street's excesses blew up the global economy, and the scandals just keep coming. Each scandal reinforces the need for tough regulation and tough enforcement. Each scandal proves over again the importance of breaking up the big banks. Each scandal raises the question of personal responsibility. How come borrowers are prosecuted for defrauding their banks, but bankers seem never to be prosecuted for defrauding their customers? George Osborne, the conservative British chancellor of the Exchequer, put it succinctly: "Fraud is a crime in ordinary business -- why shouldn't it be so in banking?" He is demanding action: "Punish wrongdoing. Right the wrong of the age of irresponsibility."

We haven't heard anything like that out of Washington. Libor-gate once more exposes how lax this administration has been on the banks -- and how irresponsible and, frankly, craven Republicans and Mitt Romney have been on this question. Romney echoes the know-nothing Republican right's call for repealing what little bank regulation has been passed since the financial collapse -- primarily the Dodd-Frank legislation. He touts deregulation in the wake of a global economic calamity caused in large part by the misguided belief that banks can police themselves.

Not surprisingly, Romney and Republicans are raking in donations from Wall Street. But they are catering to banksters that know no shame. For example, one of the most powerful Wall Street lobbying groups is the Securities Industry and Financial Markets Association, which has been leading the drive to weaken Dodd-Frank and exempt derivatives from transparency. Its chair was Jerry del Missier, the COO of Barclays, who lost his job and apparently his chairmanship in Libor-gate. Why are we not surprised?

Last January, Barclays' hard-edged CEO Robert E. Diamond Jr. announced that it was time for bankers to get their brass back. "There was a period of remorse and apology for banks," he declared. "I think that period is over." More and more of the customers defrauded by bankers might agree. They are tired of fake remorse and ritual apology. That period is over. It is time for prosecutions to begin.