Mubarak's 300,000-Strong Army of Thugs Remains in Business Despite Elections

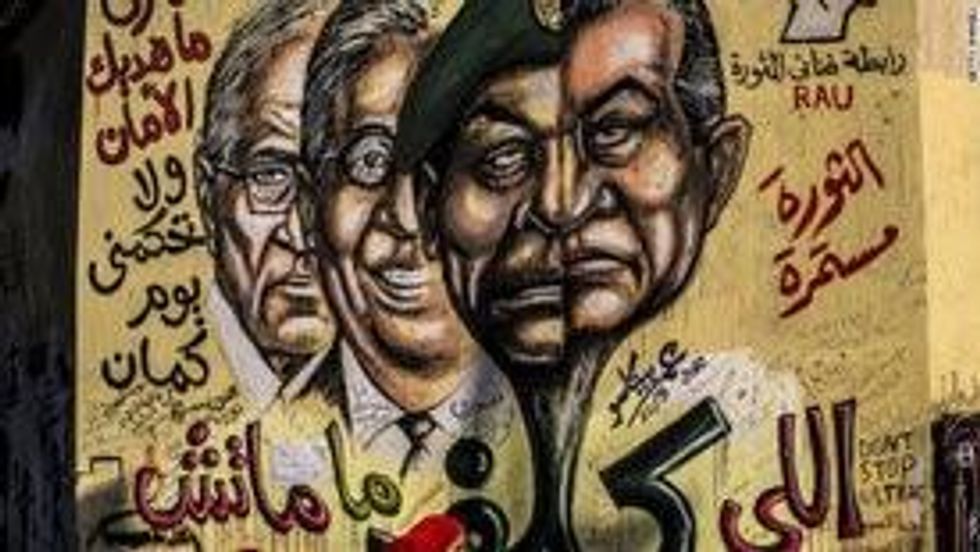

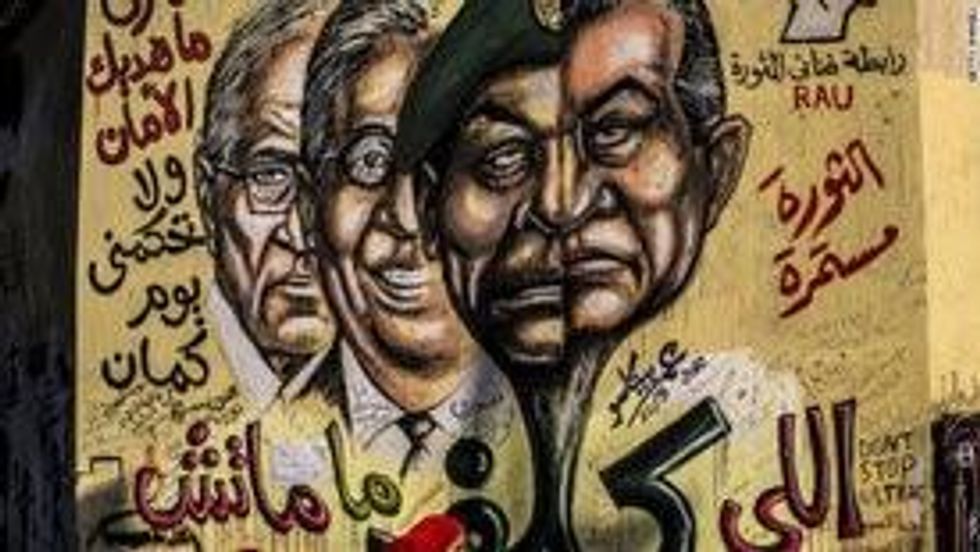

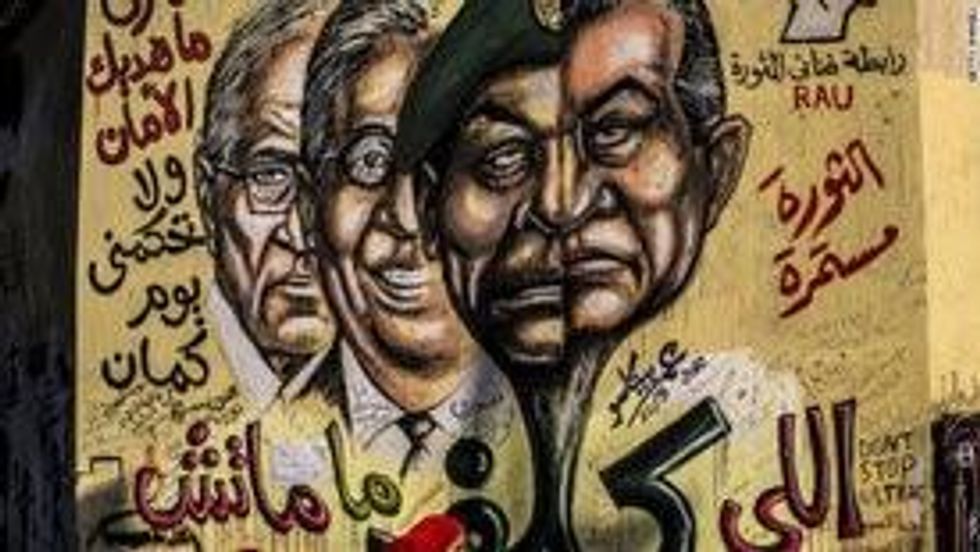

The military has played a shrewd game – insisting Mubarak go on trial while realigning supporters to preserve their privileges

As millions of Egyptians turn their backs on the brave young revolutionaries of Tahrir Square, today is the day to remember old General Mohammed Neguib, who kicked off Egypt's first post-war revolution by plotting the overthrow of King Farouk almost exactly 60 years ago. He and his fellow Egyptian army officers had been debating whether to execute the obese Farouk or send him into exile. Nasser opted to shoot the monarch. Neguib asked for a vote. In the early hours, Nasser wrote a note to Neguib: "The Liberation Movement should get rid of Faruk [sic] as quickly as possible in order to deal with what is more important - namely, the need to purge the country of the corruption that Faruk will leave behind him. We must pave the way towards a new era in which the people will enjoy their sovereign rights and live in dignity. Justice is one of our objectives. We cannot execute Faruk without a trial. Neither can we afford to keep him in jail and preoccupy ourselves with the rights and wrongs of his case at the risk of neglecting the other purposes of the revolution. Let us spare Faruk and send him into exile. History will sentence him to death."

The association of corruption with the ancien regime has been a staple of all revolutions. Justice sounds good. And today's Egyptians still demand dignity. But surely Nasser got it right; better to chuck the old boy out of the country than to stage a distracting and time-consuming trial when the future of Egypt, the "other purposes of the revolution", should be debated. Today's military played an equally shrewd but different game: they insisted Mubarak go on trial - bread and circuses for the masses, dramatic sentences to keep their minds off the future - while realigning the old Mubarakites to preserve their own privileges.

The ex-elected head of the judges' club in Egypt, Zakaria Abdul-Aziz, has rightly pointed out that even if Mubarak was put on trial, the January-February 2011 killing went on for days, "and they [the generals] did not order anyone to stop it. The Ministry of Interior is not the only place that should be cleansed. The judiciary needs that."

It was Mubarak's senior judges who permitted the deposed dictator's last Prime Minister, Ahmed Shafik, to stand in this weekend's run-off for President. As Omar Ashour, an academic in both Exeter and Doha, has observed, "when protesters stormed the State Security Investigations [SSI] headquarters and other governorates in March 2011, torture rooms and equipment were found in every building".

And what happened to the lads who ran these vicious institutions for Mubarak, clad alternatively in French-designed suits or uniforms dripping with epaulettes? They got off scot-free. Here are some names for The Independent's readers to stick in their files: Hassan Abdul-Rahman, head of the SSI; Ahmed Ramzi, head of Central Security Forces (CSF); Adly Fayyed, head of "Public Security"; Ossama Youssef, head of the Giza Security Directorate; Ismail al-Shaer, boss of the Cairo Security Directorate - "shaer", by the way, means "poet" - and Omar Faramawy, who ran the 6 October Security Directorate.

I will not use the words "culture of impunity" - as Omar Ashour does without irony - but the acquittal of the above gentlemen means that Mubarak's 300,000-strong SSI and CSF thugs are still in business. It is impossible to believe the Supreme Council of the Armed Forces - still running Egypt and commanded by Mubarak's old mate Field Marshal Tantawi - was unaware of the implications of this extraordinary state of affairs. If Mubarak represented Faruk, and his sons Gamal and Alaa the future leaders of the royal family, then the 2011 Egyptian revolution represented 1952 without the king's exile and with a shadow monarchy still in power.

The belief among journalists and academics that Tahrir Square would fill once again with the young of last year's rebellion, that a new protest movement in its millions would end this state of affairs, has - so far - proved unrealistic. Over the weekend, Egyptians wanted to vote rather than demonstrate - even if the country's security apparatus would end up running the show as usual - and if this is democracy, then it's going to be of the Algerian rather than the Tunisian variety. Maybe I just don't like armies, while Egyptians do.

But let's go back to Neguib. He went aboard the royal yacht in July 1952 to say goodbye to the king he was deposing. "I hope you'll take good care of the army," Farouk told him. "My grandfather, you know, created it." Neguib replied: "The Egyptian army is in good hands." And Farouk's last words to the general? "Your task will be difficult. It isn't easy, you know, to govern Egypt..."

Neguib concluded that governing would be easier for the military because "we were at one with the Egyptian people". Indeed. Then Nasser kicked out Neguib, prisons reopened and torturers were installed. Then came General Sadat and General Mubarak. And now?

An Urgent Message From Our Co-Founder

Dear Common Dreams reader, The U.S. is on a fast track to authoritarianism like nothing I've ever seen. Meanwhile, corporate news outlets are utterly capitulating to Trump, twisting their coverage to avoid drawing his ire while lining up to stuff cash in his pockets. That's why I believe that Common Dreams is doing the best and most consequential reporting that we've ever done. Our small but mighty team is a progressive reporting powerhouse, covering the news every day that the corporate media never will. Our mission has always been simple: To inform. To inspire. And to ignite change for the common good. Now here's the key piece that I want all our readers to understand: None of this would be possible without your financial support. That's not just some fundraising cliche. It's the absolute and literal truth. We don't accept corporate advertising and never will. We don't have a paywall because we don't think people should be blocked from critical news based on their ability to pay. Everything we do is funded by the donations of readers like you. Will you donate now to help power the nonprofit, independent reporting of Common Dreams? Thank you for being a vital member of our community. Together, we can keep independent journalism alive when it’s needed most. - Craig Brown, Co-founder |

As millions of Egyptians turn their backs on the brave young revolutionaries of Tahrir Square, today is the day to remember old General Mohammed Neguib, who kicked off Egypt's first post-war revolution by plotting the overthrow of King Farouk almost exactly 60 years ago. He and his fellow Egyptian army officers had been debating whether to execute the obese Farouk or send him into exile. Nasser opted to shoot the monarch. Neguib asked for a vote. In the early hours, Nasser wrote a note to Neguib: "The Liberation Movement should get rid of Faruk [sic] as quickly as possible in order to deal with what is more important - namely, the need to purge the country of the corruption that Faruk will leave behind him. We must pave the way towards a new era in which the people will enjoy their sovereign rights and live in dignity. Justice is one of our objectives. We cannot execute Faruk without a trial. Neither can we afford to keep him in jail and preoccupy ourselves with the rights and wrongs of his case at the risk of neglecting the other purposes of the revolution. Let us spare Faruk and send him into exile. History will sentence him to death."

The association of corruption with the ancien regime has been a staple of all revolutions. Justice sounds good. And today's Egyptians still demand dignity. But surely Nasser got it right; better to chuck the old boy out of the country than to stage a distracting and time-consuming trial when the future of Egypt, the "other purposes of the revolution", should be debated. Today's military played an equally shrewd but different game: they insisted Mubarak go on trial - bread and circuses for the masses, dramatic sentences to keep their minds off the future - while realigning the old Mubarakites to preserve their own privileges.

The ex-elected head of the judges' club in Egypt, Zakaria Abdul-Aziz, has rightly pointed out that even if Mubarak was put on trial, the January-February 2011 killing went on for days, "and they [the generals] did not order anyone to stop it. The Ministry of Interior is not the only place that should be cleansed. The judiciary needs that."

It was Mubarak's senior judges who permitted the deposed dictator's last Prime Minister, Ahmed Shafik, to stand in this weekend's run-off for President. As Omar Ashour, an academic in both Exeter and Doha, has observed, "when protesters stormed the State Security Investigations [SSI] headquarters and other governorates in March 2011, torture rooms and equipment were found in every building".

And what happened to the lads who ran these vicious institutions for Mubarak, clad alternatively in French-designed suits or uniforms dripping with epaulettes? They got off scot-free. Here are some names for The Independent's readers to stick in their files: Hassan Abdul-Rahman, head of the SSI; Ahmed Ramzi, head of Central Security Forces (CSF); Adly Fayyed, head of "Public Security"; Ossama Youssef, head of the Giza Security Directorate; Ismail al-Shaer, boss of the Cairo Security Directorate - "shaer", by the way, means "poet" - and Omar Faramawy, who ran the 6 October Security Directorate.

I will not use the words "culture of impunity" - as Omar Ashour does without irony - but the acquittal of the above gentlemen means that Mubarak's 300,000-strong SSI and CSF thugs are still in business. It is impossible to believe the Supreme Council of the Armed Forces - still running Egypt and commanded by Mubarak's old mate Field Marshal Tantawi - was unaware of the implications of this extraordinary state of affairs. If Mubarak represented Faruk, and his sons Gamal and Alaa the future leaders of the royal family, then the 2011 Egyptian revolution represented 1952 without the king's exile and with a shadow monarchy still in power.

The belief among journalists and academics that Tahrir Square would fill once again with the young of last year's rebellion, that a new protest movement in its millions would end this state of affairs, has - so far - proved unrealistic. Over the weekend, Egyptians wanted to vote rather than demonstrate - even if the country's security apparatus would end up running the show as usual - and if this is democracy, then it's going to be of the Algerian rather than the Tunisian variety. Maybe I just don't like armies, while Egyptians do.

But let's go back to Neguib. He went aboard the royal yacht in July 1952 to say goodbye to the king he was deposing. "I hope you'll take good care of the army," Farouk told him. "My grandfather, you know, created it." Neguib replied: "The Egyptian army is in good hands." And Farouk's last words to the general? "Your task will be difficult. It isn't easy, you know, to govern Egypt..."

Neguib concluded that governing would be easier for the military because "we were at one with the Egyptian people". Indeed. Then Nasser kicked out Neguib, prisons reopened and torturers were installed. Then came General Sadat and General Mubarak. And now?

As millions of Egyptians turn their backs on the brave young revolutionaries of Tahrir Square, today is the day to remember old General Mohammed Neguib, who kicked off Egypt's first post-war revolution by plotting the overthrow of King Farouk almost exactly 60 years ago. He and his fellow Egyptian army officers had been debating whether to execute the obese Farouk or send him into exile. Nasser opted to shoot the monarch. Neguib asked for a vote. In the early hours, Nasser wrote a note to Neguib: "The Liberation Movement should get rid of Faruk [sic] as quickly as possible in order to deal with what is more important - namely, the need to purge the country of the corruption that Faruk will leave behind him. We must pave the way towards a new era in which the people will enjoy their sovereign rights and live in dignity. Justice is one of our objectives. We cannot execute Faruk without a trial. Neither can we afford to keep him in jail and preoccupy ourselves with the rights and wrongs of his case at the risk of neglecting the other purposes of the revolution. Let us spare Faruk and send him into exile. History will sentence him to death."

The association of corruption with the ancien regime has been a staple of all revolutions. Justice sounds good. And today's Egyptians still demand dignity. But surely Nasser got it right; better to chuck the old boy out of the country than to stage a distracting and time-consuming trial when the future of Egypt, the "other purposes of the revolution", should be debated. Today's military played an equally shrewd but different game: they insisted Mubarak go on trial - bread and circuses for the masses, dramatic sentences to keep their minds off the future - while realigning the old Mubarakites to preserve their own privileges.

The ex-elected head of the judges' club in Egypt, Zakaria Abdul-Aziz, has rightly pointed out that even if Mubarak was put on trial, the January-February 2011 killing went on for days, "and they [the generals] did not order anyone to stop it. The Ministry of Interior is not the only place that should be cleansed. The judiciary needs that."

It was Mubarak's senior judges who permitted the deposed dictator's last Prime Minister, Ahmed Shafik, to stand in this weekend's run-off for President. As Omar Ashour, an academic in both Exeter and Doha, has observed, "when protesters stormed the State Security Investigations [SSI] headquarters and other governorates in March 2011, torture rooms and equipment were found in every building".

And what happened to the lads who ran these vicious institutions for Mubarak, clad alternatively in French-designed suits or uniforms dripping with epaulettes? They got off scot-free. Here are some names for The Independent's readers to stick in their files: Hassan Abdul-Rahman, head of the SSI; Ahmed Ramzi, head of Central Security Forces (CSF); Adly Fayyed, head of "Public Security"; Ossama Youssef, head of the Giza Security Directorate; Ismail al-Shaer, boss of the Cairo Security Directorate - "shaer", by the way, means "poet" - and Omar Faramawy, who ran the 6 October Security Directorate.

I will not use the words "culture of impunity" - as Omar Ashour does without irony - but the acquittal of the above gentlemen means that Mubarak's 300,000-strong SSI and CSF thugs are still in business. It is impossible to believe the Supreme Council of the Armed Forces - still running Egypt and commanded by Mubarak's old mate Field Marshal Tantawi - was unaware of the implications of this extraordinary state of affairs. If Mubarak represented Faruk, and his sons Gamal and Alaa the future leaders of the royal family, then the 2011 Egyptian revolution represented 1952 without the king's exile and with a shadow monarchy still in power.

The belief among journalists and academics that Tahrir Square would fill once again with the young of last year's rebellion, that a new protest movement in its millions would end this state of affairs, has - so far - proved unrealistic. Over the weekend, Egyptians wanted to vote rather than demonstrate - even if the country's security apparatus would end up running the show as usual - and if this is democracy, then it's going to be of the Algerian rather than the Tunisian variety. Maybe I just don't like armies, while Egyptians do.

But let's go back to Neguib. He went aboard the royal yacht in July 1952 to say goodbye to the king he was deposing. "I hope you'll take good care of the army," Farouk told him. "My grandfather, you know, created it." Neguib replied: "The Egyptian army is in good hands." And Farouk's last words to the general? "Your task will be difficult. It isn't easy, you know, to govern Egypt..."

Neguib concluded that governing would be easier for the military because "we were at one with the Egyptian people". Indeed. Then Nasser kicked out Neguib, prisons reopened and torturers were installed. Then came General Sadat and General Mubarak. And now?