"Mistakes Were Made": One-Time Object of Derision Now a Core Template of Our Social Behaviors

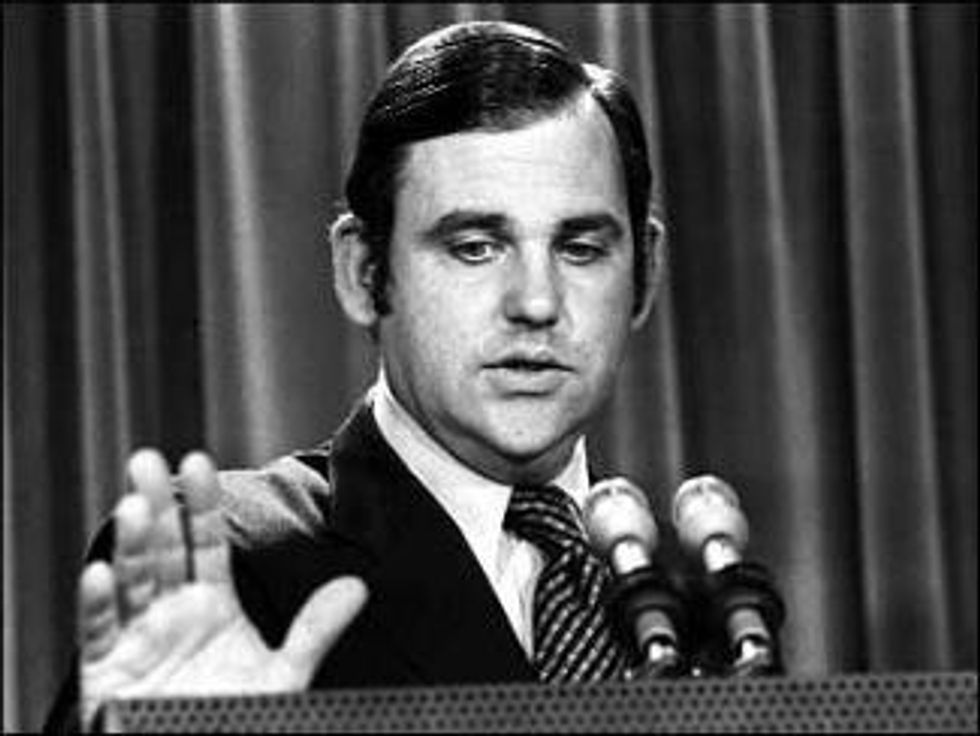

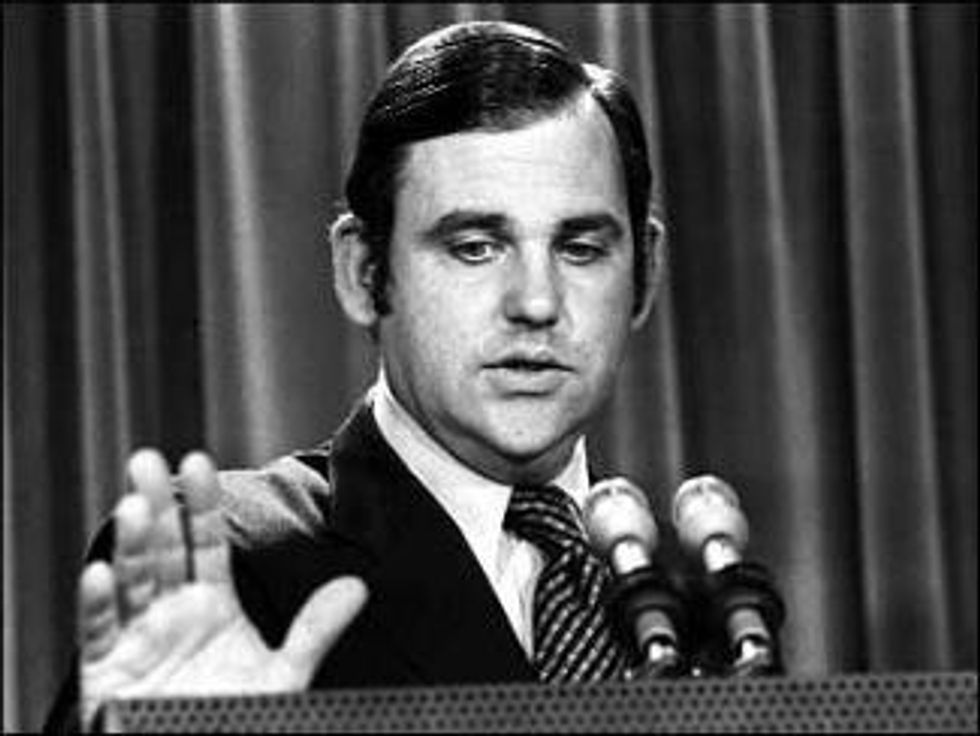

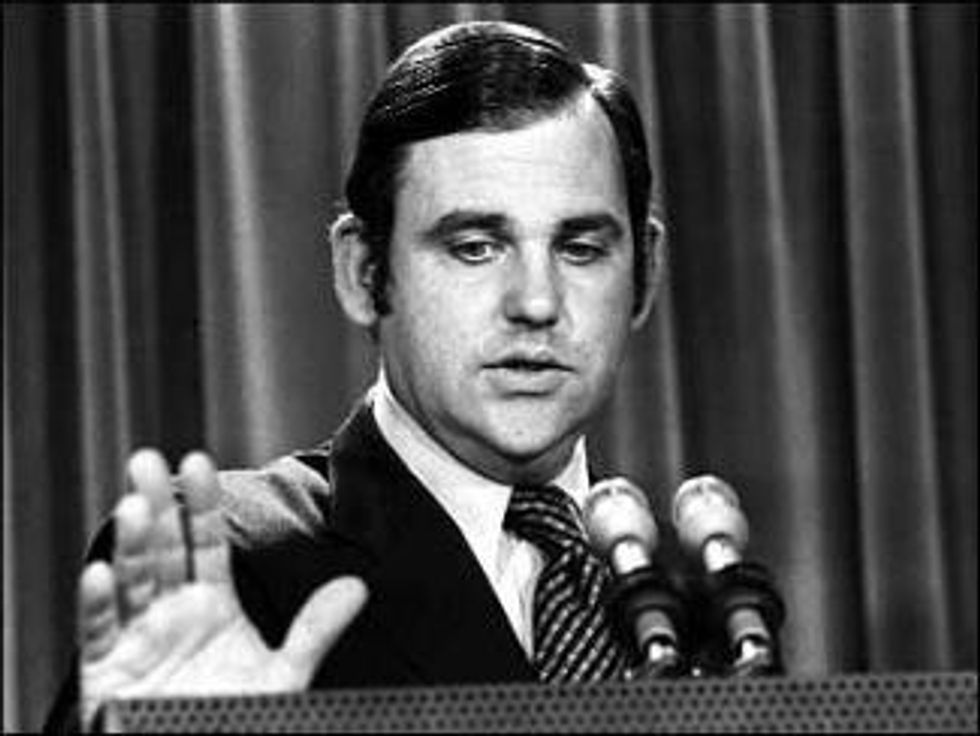

Though I was fairly young at the time, I will always remember the moment in the Spring of 1973 when Nixon's Press Secretary, Ron Ziegler, tried to explain away his and his bosses previous lies about the fast-progressing Watergate scandal with the words, "mistakes were made".

Though I was fairly young at the time, I will always remember the moment in the Spring of 1973 when Nixon's Press Secretary, Ron Ziegler, tried to explain away his and his bosses previous lies about the fast-progressing Watergate scandal with the words, "mistakes were made".

If the truth be told, I can't say I have a very clear recollection of actually seeing president's spinmeister say the famous phrase live on TV. Rather, my "memories" of the event are derived almost wholly from the comments Ziegler's words evoked among the adult members of my family.

Particularly memorable were (and are) the derisive hoots of my Aunt Kathleen, an fiercely intelligent women who, I am pretty sure, never voted anything but a straight Republican ticket in the course of her long and eventful life.

Why was Kay, as we called her, so exercised with the chief spokesman of her party's President?

Because his clumsy attempt to have the "chalice" of responsibility "pass from his lips", violated everything she had been taught about how individuals and collective entities engender better futures. She understood quite fundamentally that without reckoning for deeds done, there could be no meaningful move toward moral renewal.

Ziegler's utterances also offended her deeply felt and conscientiously lived ideas about the importance of clear and precise language.

Though we often talk about ideas and words as if they were two separate categories, this is not really the case. Cognitive and linguistic studies strongly suggest that thought is highly dependent on language; one's ability to generate complex and precise ideas is largely--though not exclusively--regulated and delimited by the complexity and precision of his or her available linguistic resources.

To use one's high pubic position to deliberately circulate obfuscating language was, as my aunt saw it, to commit an act of vandalism against the virtual republic of words, and from there, the very real republic of human beings which is absolutely dependent on transparent and rational language for its proper and peaceful functioning.

And my aunt was not alone.

For most of the next decade, Ron Ziegler was widely viewed as a joke, the prototype of the oily dissembler who should have no place in the government of a sober and serious country.

Ziegler died in 2003. Were he alive today, however, he would have to be feeling pretty good.

Why? Because the type of evasive and corrupted language for which he was repeatedly pilloried for using as Nixon's press secretary is not only accepted, but heartily and shamelessly embraced as a norm of political and social conduct.

Back then, Ziegler's famous "explanation" generated outrage and ridicule because, with it, he sought to do something that most of his audience last attempted in grade school: remove all hint of personal agency from actions that were clearly and demonstrably of his (and his fellow Nixonians) own making.

The habit of suspending of personal agency, and with it, the search for moral responsibility, is now visible all around us. It is perhaps immediately visible on the level of our financial, military and political elites.

Who caused the financial meltdown? Who has caused the anger which has made this country an object of hatred in the Middle East and elsewhere? Who has destroyed the most basic precepts of humanitarian and constitutional behavior in this country?

Those of us with the time and inclination to read beyond the pablum churned out by the mainstream media (including the liberal's beloved NPR) know many, if not most of the answers to these questions. If asked, we can make detailed lists of the key players in each disaster and can also probably even reference key documents and meeting within each depressing saga.

But, of course, most people we live and work with, never ask. And if we begin to spontaneously "share" what we know, most will quickly change the subject. And if this doesn't work, they will generally move to tactic number two: question the reliability and legitimacy of the information you are providing.

It doesn't matter that they have absolutely no fact-based means of refuting what you say or for questioning the reliability of your sources. That is wholly beside the point. What they are really seeking to do is to end the conversation before it starts.

Why? Because most of them have long-since accepted the premise that most of the forces shaping work and political spheres of their lives are inscrutable.

When one of us provides information that suggests that not only are these forces not inscrutable, but are, in fact, readily identifiable, we challenge them to use parts of their brain and their spirit that they have long since placed on consignment.

And this to me is the most pernicious legacy of the shameless dissembling introduced into our public discourse by Ziegler and his ilk in the early seventies.

Politicians have always lied. What Ziegler did was introduce the art of lying about lying. And despite the derisive hoots of my aunt and other like her, the tactic persisted and eventually went mainstream.

Now after four decades of consuming artfully deployed layers of deceptive and imprecise language, most Americans have abandoned the idea that it is possible to identify personal agency and/or chains of causality within the forces that shape the public portion of their lives.

Who does it benefit to have a population that views itself as essentially inert before our larger social institutions? I'll give you a hint. It's not regular citizens like you and me.

An Urgent Message From Our Co-Founder

Dear Common Dreams reader, The U.S. is on a fast track to authoritarianism like nothing I've ever seen. Meanwhile, corporate news outlets are utterly capitulating to Trump, twisting their coverage to avoid drawing his ire while lining up to stuff cash in his pockets. That's why I believe that Common Dreams is doing the best and most consequential reporting that we've ever done. Our small but mighty team is a progressive reporting powerhouse, covering the news every day that the corporate media never will. Our mission has always been simple: To inform. To inspire. And to ignite change for the common good. Now here's the key piece that I want all our readers to understand: None of this would be possible without your financial support. That's not just some fundraising cliche. It's the absolute and literal truth. We don't accept corporate advertising and never will. We don't have a paywall because we don't think people should be blocked from critical news based on their ability to pay. Everything we do is funded by the donations of readers like you. Will you donate now to help power the nonprofit, independent reporting of Common Dreams? Thank you for being a vital member of our community. Together, we can keep independent journalism alive when it’s needed most. - Craig Brown, Co-founder |

Though I was fairly young at the time, I will always remember the moment in the Spring of 1973 when Nixon's Press Secretary, Ron Ziegler, tried to explain away his and his bosses previous lies about the fast-progressing Watergate scandal with the words, "mistakes were made".

If the truth be told, I can't say I have a very clear recollection of actually seeing president's spinmeister say the famous phrase live on TV. Rather, my "memories" of the event are derived almost wholly from the comments Ziegler's words evoked among the adult members of my family.

Particularly memorable were (and are) the derisive hoots of my Aunt Kathleen, an fiercely intelligent women who, I am pretty sure, never voted anything but a straight Republican ticket in the course of her long and eventful life.

Why was Kay, as we called her, so exercised with the chief spokesman of her party's President?

Because his clumsy attempt to have the "chalice" of responsibility "pass from his lips", violated everything she had been taught about how individuals and collective entities engender better futures. She understood quite fundamentally that without reckoning for deeds done, there could be no meaningful move toward moral renewal.

Ziegler's utterances also offended her deeply felt and conscientiously lived ideas about the importance of clear and precise language.

Though we often talk about ideas and words as if they were two separate categories, this is not really the case. Cognitive and linguistic studies strongly suggest that thought is highly dependent on language; one's ability to generate complex and precise ideas is largely--though not exclusively--regulated and delimited by the complexity and precision of his or her available linguistic resources.

To use one's high pubic position to deliberately circulate obfuscating language was, as my aunt saw it, to commit an act of vandalism against the virtual republic of words, and from there, the very real republic of human beings which is absolutely dependent on transparent and rational language for its proper and peaceful functioning.

And my aunt was not alone.

For most of the next decade, Ron Ziegler was widely viewed as a joke, the prototype of the oily dissembler who should have no place in the government of a sober and serious country.

Ziegler died in 2003. Were he alive today, however, he would have to be feeling pretty good.

Why? Because the type of evasive and corrupted language for which he was repeatedly pilloried for using as Nixon's press secretary is not only accepted, but heartily and shamelessly embraced as a norm of political and social conduct.

Back then, Ziegler's famous "explanation" generated outrage and ridicule because, with it, he sought to do something that most of his audience last attempted in grade school: remove all hint of personal agency from actions that were clearly and demonstrably of his (and his fellow Nixonians) own making.

The habit of suspending of personal agency, and with it, the search for moral responsibility, is now visible all around us. It is perhaps immediately visible on the level of our financial, military and political elites.

Who caused the financial meltdown? Who has caused the anger which has made this country an object of hatred in the Middle East and elsewhere? Who has destroyed the most basic precepts of humanitarian and constitutional behavior in this country?

Those of us with the time and inclination to read beyond the pablum churned out by the mainstream media (including the liberal's beloved NPR) know many, if not most of the answers to these questions. If asked, we can make detailed lists of the key players in each disaster and can also probably even reference key documents and meeting within each depressing saga.

But, of course, most people we live and work with, never ask. And if we begin to spontaneously "share" what we know, most will quickly change the subject. And if this doesn't work, they will generally move to tactic number two: question the reliability and legitimacy of the information you are providing.

It doesn't matter that they have absolutely no fact-based means of refuting what you say or for questioning the reliability of your sources. That is wholly beside the point. What they are really seeking to do is to end the conversation before it starts.

Why? Because most of them have long-since accepted the premise that most of the forces shaping work and political spheres of their lives are inscrutable.

When one of us provides information that suggests that not only are these forces not inscrutable, but are, in fact, readily identifiable, we challenge them to use parts of their brain and their spirit that they have long since placed on consignment.

And this to me is the most pernicious legacy of the shameless dissembling introduced into our public discourse by Ziegler and his ilk in the early seventies.

Politicians have always lied. What Ziegler did was introduce the art of lying about lying. And despite the derisive hoots of my aunt and other like her, the tactic persisted and eventually went mainstream.

Now after four decades of consuming artfully deployed layers of deceptive and imprecise language, most Americans have abandoned the idea that it is possible to identify personal agency and/or chains of causality within the forces that shape the public portion of their lives.

Who does it benefit to have a population that views itself as essentially inert before our larger social institutions? I'll give you a hint. It's not regular citizens like you and me.

Though I was fairly young at the time, I will always remember the moment in the Spring of 1973 when Nixon's Press Secretary, Ron Ziegler, tried to explain away his and his bosses previous lies about the fast-progressing Watergate scandal with the words, "mistakes were made".

If the truth be told, I can't say I have a very clear recollection of actually seeing president's spinmeister say the famous phrase live on TV. Rather, my "memories" of the event are derived almost wholly from the comments Ziegler's words evoked among the adult members of my family.

Particularly memorable were (and are) the derisive hoots of my Aunt Kathleen, an fiercely intelligent women who, I am pretty sure, never voted anything but a straight Republican ticket in the course of her long and eventful life.

Why was Kay, as we called her, so exercised with the chief spokesman of her party's President?

Because his clumsy attempt to have the "chalice" of responsibility "pass from his lips", violated everything she had been taught about how individuals and collective entities engender better futures. She understood quite fundamentally that without reckoning for deeds done, there could be no meaningful move toward moral renewal.

Ziegler's utterances also offended her deeply felt and conscientiously lived ideas about the importance of clear and precise language.

Though we often talk about ideas and words as if they were two separate categories, this is not really the case. Cognitive and linguistic studies strongly suggest that thought is highly dependent on language; one's ability to generate complex and precise ideas is largely--though not exclusively--regulated and delimited by the complexity and precision of his or her available linguistic resources.

To use one's high pubic position to deliberately circulate obfuscating language was, as my aunt saw it, to commit an act of vandalism against the virtual republic of words, and from there, the very real republic of human beings which is absolutely dependent on transparent and rational language for its proper and peaceful functioning.

And my aunt was not alone.

For most of the next decade, Ron Ziegler was widely viewed as a joke, the prototype of the oily dissembler who should have no place in the government of a sober and serious country.

Ziegler died in 2003. Were he alive today, however, he would have to be feeling pretty good.

Why? Because the type of evasive and corrupted language for which he was repeatedly pilloried for using as Nixon's press secretary is not only accepted, but heartily and shamelessly embraced as a norm of political and social conduct.

Back then, Ziegler's famous "explanation" generated outrage and ridicule because, with it, he sought to do something that most of his audience last attempted in grade school: remove all hint of personal agency from actions that were clearly and demonstrably of his (and his fellow Nixonians) own making.

The habit of suspending of personal agency, and with it, the search for moral responsibility, is now visible all around us. It is perhaps immediately visible on the level of our financial, military and political elites.

Who caused the financial meltdown? Who has caused the anger which has made this country an object of hatred in the Middle East and elsewhere? Who has destroyed the most basic precepts of humanitarian and constitutional behavior in this country?

Those of us with the time and inclination to read beyond the pablum churned out by the mainstream media (including the liberal's beloved NPR) know many, if not most of the answers to these questions. If asked, we can make detailed lists of the key players in each disaster and can also probably even reference key documents and meeting within each depressing saga.

But, of course, most people we live and work with, never ask. And if we begin to spontaneously "share" what we know, most will quickly change the subject. And if this doesn't work, they will generally move to tactic number two: question the reliability and legitimacy of the information you are providing.

It doesn't matter that they have absolutely no fact-based means of refuting what you say or for questioning the reliability of your sources. That is wholly beside the point. What they are really seeking to do is to end the conversation before it starts.

Why? Because most of them have long-since accepted the premise that most of the forces shaping work and political spheres of their lives are inscrutable.

When one of us provides information that suggests that not only are these forces not inscrutable, but are, in fact, readily identifiable, we challenge them to use parts of their brain and their spirit that they have long since placed on consignment.

And this to me is the most pernicious legacy of the shameless dissembling introduced into our public discourse by Ziegler and his ilk in the early seventies.

Politicians have always lied. What Ziegler did was introduce the art of lying about lying. And despite the derisive hoots of my aunt and other like her, the tactic persisted and eventually went mainstream.

Now after four decades of consuming artfully deployed layers of deceptive and imprecise language, most Americans have abandoned the idea that it is possible to identify personal agency and/or chains of causality within the forces that shape the public portion of their lives.

Who does it benefit to have a population that views itself as essentially inert before our larger social institutions? I'll give you a hint. It's not regular citizens like you and me.