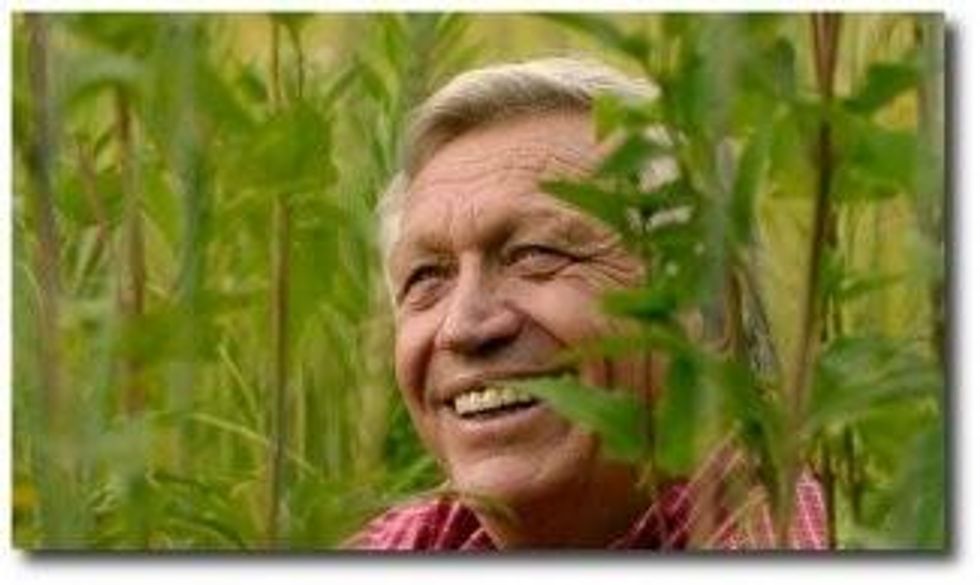

Wes Jackson spent the weekend at The Land Institute's annual Prairie Festival talking up -- with his usual precision and passion -- the science and strategy behind plans to revolutionize the way we grow food using perennial polyculture grains.

A leading figure in the sustainable agriculture movement, Jackson has been pursuing the science and tweaking the strategy for more than three decades, building an impressive body of knowledge with his colleagues at "The Land," as it's known to everyone there. (The group also has produced an impressive full-bodied bread that was on the dinner table during the festival, made from an intermediate wheatgrass grain they've developed and dubbed "Kernza.")

But, perhaps ironically, my faith in Jackson's vision deepens not when he speaks from the depth of his knowledge (or when people happily bite into the bread) but when he emphasizes the uncertainty of what he knows. More on that, after some background.

Jackson, who co-founded the research center in 1976 after leaving his job as an environmental studies professor at California State University-Sacramento, believes that shifting from fragile annual monocultures to more hearty perennial grains grown in a mixture of plants (polycultures) is the key to a truly sustainable agriculture. Instead of a brittle industrial agriculture dependent on fossil fuels, Jackson's research team is working to build a resilient agriculture modeled on natural ecosystems.

A plant geneticist who grew up farming, Jackson's experiences in the fields and the laboratory give him the credentials to talk authoritatively about how to develop agricultural practices capable of producing healthful food without the soil erosion and contamination that comes with today's highly toxic conventional agriculture. Delivering that message with a style that hybridizes the prairie pulpit and the graduate seminar, Jackson inspired the Prairie Festival audience in Salina, KS, with his sketch of the next step -- taking The Land's work international in the coming decades.

When he gets revved up in front of an audience, Jackson is eager to share all that he knows, but one of the things he knows is the danger that comes with being sure you have the answers.

After the festival ended, Jackson made the rounds of the lunch tables to chat up folks informally. Leaning into one group, the topic turned to the problem of arrogance and certainty, and Jackson suggested an important first step to solving big problems such as agriculture is recognizing that sometimes "we've got to give up on what we know."

If there was one sign he could hang above everyone's desk, Jackson said, it would be this daily affirmation: "This day I will do everything I can to fight the problem of reassertion." Reasserting, over and over again, what we think we know is trouble, especially in the sciences, he said.

Don't mistake Jackson's warning for the anti-science, know-nothing rhetoric that is popular in some conservative circles. He's trying to bolster, not undermine, faith in science by encouraging scientists not to get stuck in comfortable approaches. In agriculture, such inertia has led researchers to assume that the so-called "Green Revolution" emphasis on chemicals is the only way to maintain high yields. Research in initiatives such as perennial polyculture grains, Jackson argues, may well reveal the conventional wisdom to be conventional foolhardiness.

With the health of our soils and our own bodies at stake, Jackson says, we can't afford to assume old approaches can cope with coming crises. Because humans like to resolve ambiguity, we reward researchers who appear to do that within existing systems -- such research may be right but irrelevant, if the real problem is at the level of the whole system. Solving individual problems within a system that can't be sustained actually creates problems.

Jackson believes that's the trap of much of contemporary research into agriculture, and that's why he's hoping to find support for an ambitious program to fund new research into The Land Institute's approach to sustainability in partnership with other researchers and institutions around the world. He's confident in the basics but recognizes how much work in the lab and the research plots remains.

He also recognizes that science alone won't solve the problem; serious changes are necessary in economic, political, and social systems. He diagnoses a large part of the problem of those systems to be their love of abstraction. In contemporary financial capitalism, for example, countless decisions about money are based on abstraction, not on the reality of economics rooted in ecosystems.

"Milton and Blake both acknowledged that the demonic is the abstraction without the particular," said Jackson, who's as likely to quote poets and philosophers as scientists.

The particular is the reality, and science helps us understand it only when it remains rooted in that particularity. Farmers work the land in a specific place within a specific ecosystem, where they must attend to the uniqueness of place, Jackson said. That means an idea such as perennial polycultures is valuable not as a monolithic answer in the abstract, but as an idea tested out in specific places, whether that be wheat fields in Kansas or rice paddies in the Philippines. Jackson is not out to make The Land Institute the center of sustainable agriculture, but instead wants to see the ideas developed in as many places as it is sensible.

Jackson also cautions that our specific places must be understood as part of larger systems. To experience our place in that larger living world, sometimes we have to step outside of science.

Jackson offered an example. We know the earth revolves around the sun, but our daily experience is of standing on ground that doesn't move. To correct that, he said we should take the time to feel the earth move. Jackson was off and running:

"I have actually felt the earth turn. I can tell you how to do that. I've gone out there and laid down on the hill when the moon is full, and if you will look when the moon is coming up in the east and the sun is setting in the west -- you've got to live in Kansas to do that, or Nebraska, someplace flat -- and you can actually feel the earth turn. Do that sometime. It's a great moment. You've got to do that extra exercise to experience reality. Otherwise we live with the illusion," Jackson said, pausing before adding, "which is fun enough."

Jackson took a moment to delight both in his memory of the experience and the smiles on the faces of the people at the table. Then he smiled and, before moving on to the next table, said, "I suppose that in order to experience reality, you have to be a mystic."