New Deal's Legacy in Danger of Being Ruined

Many of those who worked for the New Deal believed that they were building a civilization. They left us thousands of schools, colleges, bridges, dams, murals, parks and aqueducts, now falling into ruin, as did those of ancient Rome. To recover their vision, we must relearn an ethical language now as alien as Latin. It speaks to us from the buildings New Dealers left in their faith that we would continue to build toward greater human happiness and opportunity.

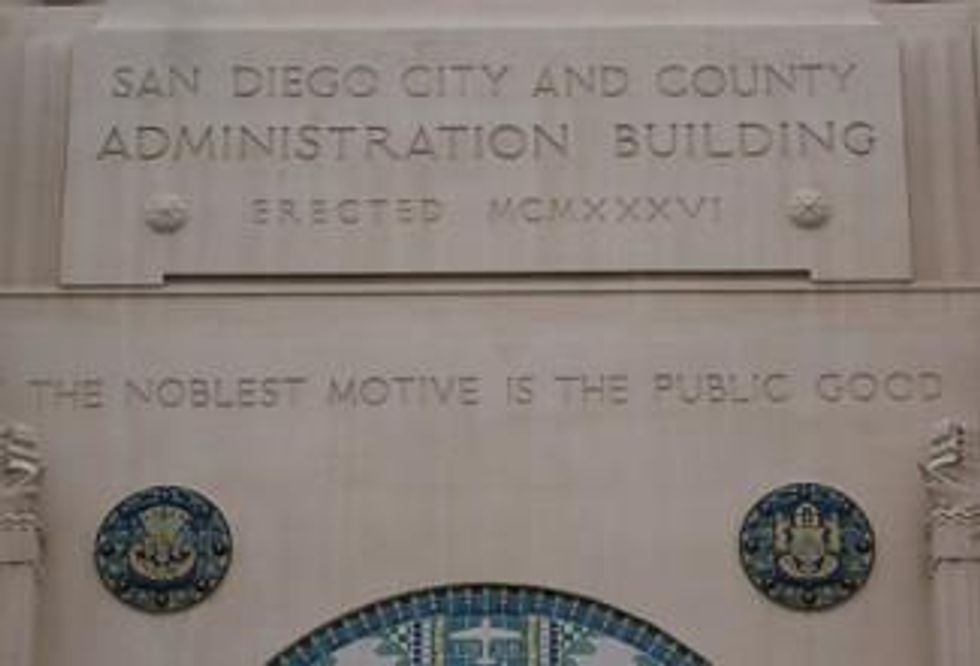

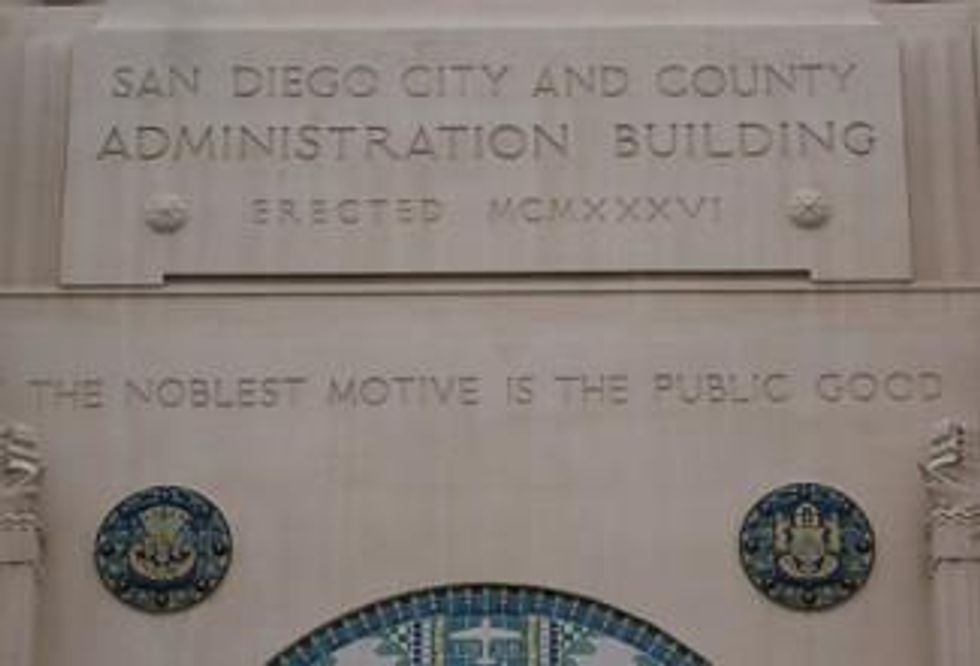

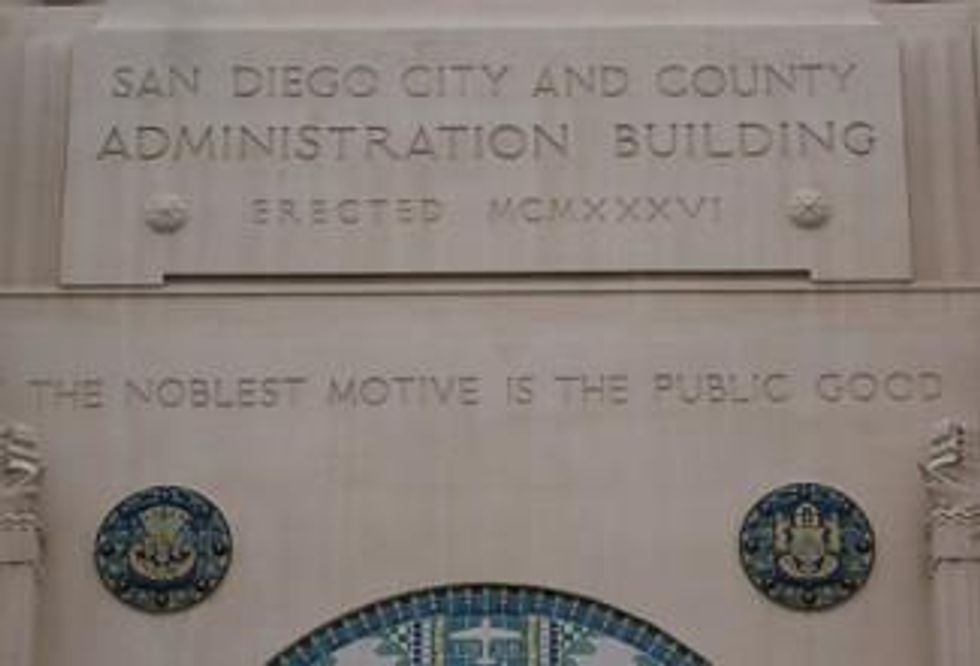

"The noblest motive is the public good," declares an inscription from Virgil on San Diego's County Administration Building. A terrazzo floor in its rotunda proclaims, "Good government requires the intelligent interest of every citizen."

A Deco relief of St. George slaying the dragon of ignorance on Berkeley High School bears a text panel announcing, "You shall know the truth and the truth shall make you free." That, after all, was what the public education we are told we can no longer afford was ideally all about.

All of these structures share a common origin: They mushroomed in the brief spasm of public building activity launched by President Franklin D. Roosevelt's New Deal. They were designed to lift the country out of the Great Depression by giving millions work, but they did something else as well: They speak to us in the language with which Roosevelt infused the nation in order to keep it united during that economic calamity.

A generation had to pass before millions so took for granted the social benefits and security bestowed upon them by the New Deal that they could elect an equally accomplished communicator devoted to its repeal. When Ronald Reagan told Americans that government is not a solution but the problem itself, he corroded the very foundations of democracy by which "we the people" formed "a more perfect union." Whereas FDR spoke of government in the first-person plural, Reagan and his acolytes have done so in the third person, not as "we" but as "it" and "them." By making government and its employees the enemy, Reagan made a rhetorical shift that has withered the very notion of social progress once synonymous with the United States.

In his 2005 book, "Going Postal," Mark Ames notes that the attack upon public servants began even before Reagan with the partial privatization of the U.S. Postal Service in 1971. The onslaught has snowballed since then, mounting now to open season upon "greedy" teachers, librarians, nurses, social workers, and even first responders in Wisconsin and elsewhere.

As the New Deal's enemies have vilified the public good to favor good for the private sector, Virgil's declaration has grown virtually incomprehensible. Talented men and women once flocked to public service, inspired by Roosevelt's insistence that "the test of our progress is not whether we add more to the abundance of those who have much; it is whether we provide enough for those who have too little." We are currently flunking that test.

Whether we build a civilization worthy of the name or Dodge City depends upon the language that we choose.

An Urgent Message From Our Co-Founder

Dear Common Dreams reader, The U.S. is on a fast track to authoritarianism like nothing I've ever seen. Meanwhile, corporate news outlets are utterly capitulating to Trump, twisting their coverage to avoid drawing his ire while lining up to stuff cash in his pockets. That's why I believe that Common Dreams is doing the best and most consequential reporting that we've ever done. Our small but mighty team is a progressive reporting powerhouse, covering the news every day that the corporate media never will. Our mission has always been simple: To inform. To inspire. And to ignite change for the common good. Now here's the key piece that I want all our readers to understand: None of this would be possible without your financial support. That's not just some fundraising cliche. It's the absolute and literal truth. We don't accept corporate advertising and never will. We don't have a paywall because we don't think people should be blocked from critical news based on their ability to pay. Everything we do is funded by the donations of readers like you. Will you donate now to help power the nonprofit, independent reporting of Common Dreams? Thank you for being a vital member of our community. Together, we can keep independent journalism alive when it’s needed most. - Craig Brown, Co-founder |

Many of those who worked for the New Deal believed that they were building a civilization. They left us thousands of schools, colleges, bridges, dams, murals, parks and aqueducts, now falling into ruin, as did those of ancient Rome. To recover their vision, we must relearn an ethical language now as alien as Latin. It speaks to us from the buildings New Dealers left in their faith that we would continue to build toward greater human happiness and opportunity.

"The noblest motive is the public good," declares an inscription from Virgil on San Diego's County Administration Building. A terrazzo floor in its rotunda proclaims, "Good government requires the intelligent interest of every citizen."

A Deco relief of St. George slaying the dragon of ignorance on Berkeley High School bears a text panel announcing, "You shall know the truth and the truth shall make you free." That, after all, was what the public education we are told we can no longer afford was ideally all about.

All of these structures share a common origin: They mushroomed in the brief spasm of public building activity launched by President Franklin D. Roosevelt's New Deal. They were designed to lift the country out of the Great Depression by giving millions work, but they did something else as well: They speak to us in the language with which Roosevelt infused the nation in order to keep it united during that economic calamity.

A generation had to pass before millions so took for granted the social benefits and security bestowed upon them by the New Deal that they could elect an equally accomplished communicator devoted to its repeal. When Ronald Reagan told Americans that government is not a solution but the problem itself, he corroded the very foundations of democracy by which "we the people" formed "a more perfect union." Whereas FDR spoke of government in the first-person plural, Reagan and his acolytes have done so in the third person, not as "we" but as "it" and "them." By making government and its employees the enemy, Reagan made a rhetorical shift that has withered the very notion of social progress once synonymous with the United States.

In his 2005 book, "Going Postal," Mark Ames notes that the attack upon public servants began even before Reagan with the partial privatization of the U.S. Postal Service in 1971. The onslaught has snowballed since then, mounting now to open season upon "greedy" teachers, librarians, nurses, social workers, and even first responders in Wisconsin and elsewhere.

As the New Deal's enemies have vilified the public good to favor good for the private sector, Virgil's declaration has grown virtually incomprehensible. Talented men and women once flocked to public service, inspired by Roosevelt's insistence that "the test of our progress is not whether we add more to the abundance of those who have much; it is whether we provide enough for those who have too little." We are currently flunking that test.

Whether we build a civilization worthy of the name or Dodge City depends upon the language that we choose.

Many of those who worked for the New Deal believed that they were building a civilization. They left us thousands of schools, colleges, bridges, dams, murals, parks and aqueducts, now falling into ruin, as did those of ancient Rome. To recover their vision, we must relearn an ethical language now as alien as Latin. It speaks to us from the buildings New Dealers left in their faith that we would continue to build toward greater human happiness and opportunity.

"The noblest motive is the public good," declares an inscription from Virgil on San Diego's County Administration Building. A terrazzo floor in its rotunda proclaims, "Good government requires the intelligent interest of every citizen."

A Deco relief of St. George slaying the dragon of ignorance on Berkeley High School bears a text panel announcing, "You shall know the truth and the truth shall make you free." That, after all, was what the public education we are told we can no longer afford was ideally all about.

All of these structures share a common origin: They mushroomed in the brief spasm of public building activity launched by President Franklin D. Roosevelt's New Deal. They were designed to lift the country out of the Great Depression by giving millions work, but they did something else as well: They speak to us in the language with which Roosevelt infused the nation in order to keep it united during that economic calamity.

A generation had to pass before millions so took for granted the social benefits and security bestowed upon them by the New Deal that they could elect an equally accomplished communicator devoted to its repeal. When Ronald Reagan told Americans that government is not a solution but the problem itself, he corroded the very foundations of democracy by which "we the people" formed "a more perfect union." Whereas FDR spoke of government in the first-person plural, Reagan and his acolytes have done so in the third person, not as "we" but as "it" and "them." By making government and its employees the enemy, Reagan made a rhetorical shift that has withered the very notion of social progress once synonymous with the United States.

In his 2005 book, "Going Postal," Mark Ames notes that the attack upon public servants began even before Reagan with the partial privatization of the U.S. Postal Service in 1971. The onslaught has snowballed since then, mounting now to open season upon "greedy" teachers, librarians, nurses, social workers, and even first responders in Wisconsin and elsewhere.

As the New Deal's enemies have vilified the public good to favor good for the private sector, Virgil's declaration has grown virtually incomprehensible. Talented men and women once flocked to public service, inspired by Roosevelt's insistence that "the test of our progress is not whether we add more to the abundance of those who have much; it is whether we provide enough for those who have too little." We are currently flunking that test.

Whether we build a civilization worthy of the name or Dodge City depends upon the language that we choose.