Public Media and the Decommodification of News: News Behind Pay Walls is No Help to Democracy

There have been various proposals to "save journalism" from the crisis brought on by digitalization. But by and large these ideas have less to do with meeting the information needs of a democratic society than with preserving the profit potential of existing media outlets.

Take the various suggestions as to how to get news outlets to stop giving away their content for free. Among others, Walter Isaacson (formerly of Time), Steven Brill (formerly of Content) and Rupert Murdoch (formerly of Australia) have all offered suggestions for how newspapers can be saved by putting their content behind pay walls (Time, 2/5/09; PoynterOnline, 2/9/09; L.A. Times, 8/21/09).

There are several practical difficulties with these proposals. First, if one paper does this and others don't follow suit, readers will likely just migrate to the still-free sites. (This is pretty much why papers like the New York Times and L.A. Times abandoned their experiments with trying to charge for some of their online content-New York Times, 9/18/07.)

But perhaps you could get all the big papers to go in together and create subscriber-only sites all at once. This would run squarely against anti-trust laws, since competitors agreeing to charge more for their product in order to make more money is exactly what anti-trust is supposed to prevent. The solution to this, some have suggested (e.g., Tim Rutten, L.A. Times, 2/4/09), is that newspapers and other corporate news outlets ought to get an anti-trust exemption-though the Obama administration has so far been cool to the idea of approving such a journalistic cartel (Editor & Publisher, 4/22/09).

Even if news outlets were allowed to get together to set prices, of course, they would still have to compete with other websites that offer news. Publishers seem particularly exercised about competition from "aggregators": sites that automatically find and link to news stories found elsewhere, like Google News and parts of Huffington Post. Denouncing these "parasites or tech tapeworms in the intestines of the Internet" (L.A. Times, 8/21/09), corporate journalists have proposed solutions ranging from blocking incoming links to their pages (Newsweek, 9/14/09)-a simple technical fix that no one has tried because it would hurt the publishers worse than aggregators (FAIR Blog, 9/10/09)-to resurrecting the "hot news" doctrine, a 1918 Supreme Court ruling that treated "scoops" as a form of intellectual property (Slate, 4/17/09).

So far, the discussion has centered on whether or not corporate media outlets could overcome these practical and legal hurdles to make more money by restricting their content to paying customers. The more important question, though, is whether this would be a good thing.

At root, the pay-wall proposal is an attempt to turn news into a commodity again, something that people are willing to pay for. Central to the idea of a commodity is scarcity: People pay for things that aren't available to everyone, that they won't benefit from unless they can afford them. The reason there are so many uninsured people in the U.S. is because healthcare is treated as a commodity here-which inevitably means that some people aren't going to get it.

News, we are told, is different from other commodities-since an informed citizenry is essential to democracy-and that's why we need to ignore anti-trust laws to protect it. But it's actually that very importance that makes treating news as a commodity so problematic.

Murdoch's News Corp points to its Wall Street Journal as a success story with its website's 1 million paying customers, and has encouraged the New York Times Co., Washington Post Co., Hearst Corp. and Tribune Co. to follow its lead (L.A. Times, 8/21/09). WSJ.com's success has less to do with offering the paper's news articles and more to do with the company profiles that investors believe will make them money. But imagine that each of those media companies were able to match the Journal's ability to attract paying customers to their own flagship paper's walled-off website.

That would be a total 5 million people with access to the news produced by these companies-or less than 2 percent of the U.S. population. And that's assuming no overlap in their audiences. For comparison purposes, the free New York Times website alone currently has an audience estimated at 20 million.

As it is, it's not like we have a particularly well-informed electorate; if plans for an online news cartel that restricts access to paying subscribers are at all successful, though, today's voters may seem like Encyclopedia Brown.

The status quo, of course-in which the (mostly) free content of the U.S. media system relies on the underwriting of advertisers-is itself far from ideal. Any media system is ultimately going to reflect the interests of the people who foot the bills; it's wishful thinking to imagine you can get giant multinational corporations to pay for a society's informational needs without making sure that the information-gathering system preserves and protects their profits. And that's aside from the direct effects on our collective psyche of advertising itself, a corporate propaganda campaign that spends at least $120 billion annually (Reuters, 9/16/09) in an effort to reshape our thoughts and personalities in a more profitable direction.

If we want news that actually serves the interests of democracy, it can be neither a commodity in itself nor a lure to turn the attention of audiences into a commodity. This means journalism practiced for its own sake, not as a means of making a profit. But how can such journalism be sustainable? In Extra!'s "Future of Journalism" issue (7/09), we described some of the alternative models, including non-profit news outlets subsidized by foundations, and citizen journalism carried out on a largely volunteer basis.

One model we did not discuss is public media-that is, journalism funded by the citizenry via the government. In many ways, it's the obvious solution to the problem of commodity journalism: The state is one of the few institutions whose resources can compare to those of the corporate sector, and at least in theory is supposed to represent the interests of the populace as a whole.

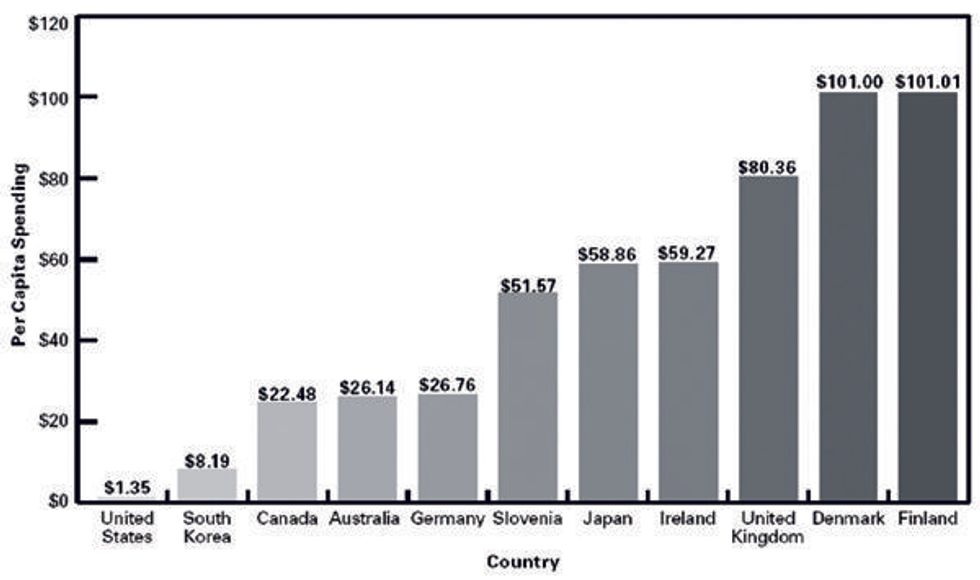

In practice, of course, governments often look out for their own interests, and those of their most powerful supporters. This has been the problem with so-called public broadcasting in the United States, whose promise has gone largely unrealized. Not only is the government funding for PBS and NPR pitifully small in comparison to the support other countries give their public systems (see chart), but the U.S. "public" broadcasters are by design dependent on massive corporate subsidies; with only 40 percent of public broadcasting revenue coming from federal, state or local government (CPB report, 9/09), it's almost impossible to get a show on "noncommercial" television in the United States unless a wealthy for-profit company is willing to buy expensive "underwriting announcements" to air before and after it. (PBS's primary news show, the NewsHour With Jim Lehrer, is mostly owned by the for-profit conglomerate Liberty Media.) And the Corporation for Public Broadcasting, which in theory is supposed to serve as a "heat shield" to protect programmers from political pressures, has in practice been turned into a vehicle for conservatives in Congress to police funding recipients for signs of dangerous ideological independence (Extra! Update, 6/05).

source: Free Press, "Public Media's Moment" Other countries, however, have produced evidence that generous public support for media can produce real results in terms of an informed citizenry. A telling study in the European Journal of Communication (3/09) looking at media systems and public knowledge in four countries-the U.S., Britain, Denmark and Finland-found that the latter two countries, which had the least-commercialized television systems, also featured the most "hard news" programming; these were also the countries with the highest level of knowledge about political affairs, both domestic and international. Particularly striking was the fact that while the United States-and Britain, to a somewhat lesser extent-showed a large gap in political knowledge between college-educated respondents and those with at most a high-school diploma, the Scandinavian countries had a uniformly high level of political awareness across educational classes.

Over the years, many ideas have been put forward about how to invigorate existing U.S. public broadcasting systems-to give them serious and secure funding and remove the levers of political interference that curtail their independence. FAIR (Extra!, 9-10/05) has suggested replacing the Corporation for Public Broadcasting with an independent trust fund that would insulate public broadcasters from partisan pressures. Free Press (5/09) released a white paper called "Public Media's Moment" with a detailed blueprint for improving the funding, governance and diversity of noncommercial broadcasting.

Of course, in a country where offering government health insurance to non-retirees is denounced as socialism, a truly public media system is a hard sell. A single-payer media system isn't the answer; there will always be a need for independent nonprofit journalistic outlets, and even for-profit news can have its place in a diverse information environment. But offering citizens a real public option when it comes to news and debate is an essential part of curing the ills of American democracy.

An Urgent Message From Our Co-Founder

Dear Common Dreams reader, The U.S. is on a fast track to authoritarianism like nothing I've ever seen. Meanwhile, corporate news outlets are utterly capitulating to Trump, twisting their coverage to avoid drawing his ire while lining up to stuff cash in his pockets. That's why I believe that Common Dreams is doing the best and most consequential reporting that we've ever done. Our small but mighty team is a progressive reporting powerhouse, covering the news every day that the corporate media never will. Our mission has always been simple: To inform. To inspire. And to ignite change for the common good. Now here's the key piece that I want all our readers to understand: None of this would be possible without your financial support. That's not just some fundraising cliche. It's the absolute and literal truth. We don't accept corporate advertising and never will. We don't have a paywall because we don't think people should be blocked from critical news based on their ability to pay. Everything we do is funded by the donations of readers like you. Will you donate now to help power the nonprofit, independent reporting of Common Dreams? Thank you for being a vital member of our community. Together, we can keep independent journalism alive when it’s needed most. - Craig Brown, Co-founder |

There have been various proposals to "save journalism" from the crisis brought on by digitalization. But by and large these ideas have less to do with meeting the information needs of a democratic society than with preserving the profit potential of existing media outlets.

Take the various suggestions as to how to get news outlets to stop giving away their content for free. Among others, Walter Isaacson (formerly of Time), Steven Brill (formerly of Content) and Rupert Murdoch (formerly of Australia) have all offered suggestions for how newspapers can be saved by putting their content behind pay walls (Time, 2/5/09; PoynterOnline, 2/9/09; L.A. Times, 8/21/09).

There are several practical difficulties with these proposals. First, if one paper does this and others don't follow suit, readers will likely just migrate to the still-free sites. (This is pretty much why papers like the New York Times and L.A. Times abandoned their experiments with trying to charge for some of their online content-New York Times, 9/18/07.)

But perhaps you could get all the big papers to go in together and create subscriber-only sites all at once. This would run squarely against anti-trust laws, since competitors agreeing to charge more for their product in order to make more money is exactly what anti-trust is supposed to prevent. The solution to this, some have suggested (e.g., Tim Rutten, L.A. Times, 2/4/09), is that newspapers and other corporate news outlets ought to get an anti-trust exemption-though the Obama administration has so far been cool to the idea of approving such a journalistic cartel (Editor & Publisher, 4/22/09).

Even if news outlets were allowed to get together to set prices, of course, they would still have to compete with other websites that offer news. Publishers seem particularly exercised about competition from "aggregators": sites that automatically find and link to news stories found elsewhere, like Google News and parts of Huffington Post. Denouncing these "parasites or tech tapeworms in the intestines of the Internet" (L.A. Times, 8/21/09), corporate journalists have proposed solutions ranging from blocking incoming links to their pages (Newsweek, 9/14/09)-a simple technical fix that no one has tried because it would hurt the publishers worse than aggregators (FAIR Blog, 9/10/09)-to resurrecting the "hot news" doctrine, a 1918 Supreme Court ruling that treated "scoops" as a form of intellectual property (Slate, 4/17/09).

So far, the discussion has centered on whether or not corporate media outlets could overcome these practical and legal hurdles to make more money by restricting their content to paying customers. The more important question, though, is whether this would be a good thing.

At root, the pay-wall proposal is an attempt to turn news into a commodity again, something that people are willing to pay for. Central to the idea of a commodity is scarcity: People pay for things that aren't available to everyone, that they won't benefit from unless they can afford them. The reason there are so many uninsured people in the U.S. is because healthcare is treated as a commodity here-which inevitably means that some people aren't going to get it.

News, we are told, is different from other commodities-since an informed citizenry is essential to democracy-and that's why we need to ignore anti-trust laws to protect it. But it's actually that very importance that makes treating news as a commodity so problematic.

Murdoch's News Corp points to its Wall Street Journal as a success story with its website's 1 million paying customers, and has encouraged the New York Times Co., Washington Post Co., Hearst Corp. and Tribune Co. to follow its lead (L.A. Times, 8/21/09). WSJ.com's success has less to do with offering the paper's news articles and more to do with the company profiles that investors believe will make them money. But imagine that each of those media companies were able to match the Journal's ability to attract paying customers to their own flagship paper's walled-off website.

That would be a total 5 million people with access to the news produced by these companies-or less than 2 percent of the U.S. population. And that's assuming no overlap in their audiences. For comparison purposes, the free New York Times website alone currently has an audience estimated at 20 million.

As it is, it's not like we have a particularly well-informed electorate; if plans for an online news cartel that restricts access to paying subscribers are at all successful, though, today's voters may seem like Encyclopedia Brown.

The status quo, of course-in which the (mostly) free content of the U.S. media system relies on the underwriting of advertisers-is itself far from ideal. Any media system is ultimately going to reflect the interests of the people who foot the bills; it's wishful thinking to imagine you can get giant multinational corporations to pay for a society's informational needs without making sure that the information-gathering system preserves and protects their profits. And that's aside from the direct effects on our collective psyche of advertising itself, a corporate propaganda campaign that spends at least $120 billion annually (Reuters, 9/16/09) in an effort to reshape our thoughts and personalities in a more profitable direction.

If we want news that actually serves the interests of democracy, it can be neither a commodity in itself nor a lure to turn the attention of audiences into a commodity. This means journalism practiced for its own sake, not as a means of making a profit. But how can such journalism be sustainable? In Extra!'s "Future of Journalism" issue (7/09), we described some of the alternative models, including non-profit news outlets subsidized by foundations, and citizen journalism carried out on a largely volunteer basis.

One model we did not discuss is public media-that is, journalism funded by the citizenry via the government. In many ways, it's the obvious solution to the problem of commodity journalism: The state is one of the few institutions whose resources can compare to those of the corporate sector, and at least in theory is supposed to represent the interests of the populace as a whole.

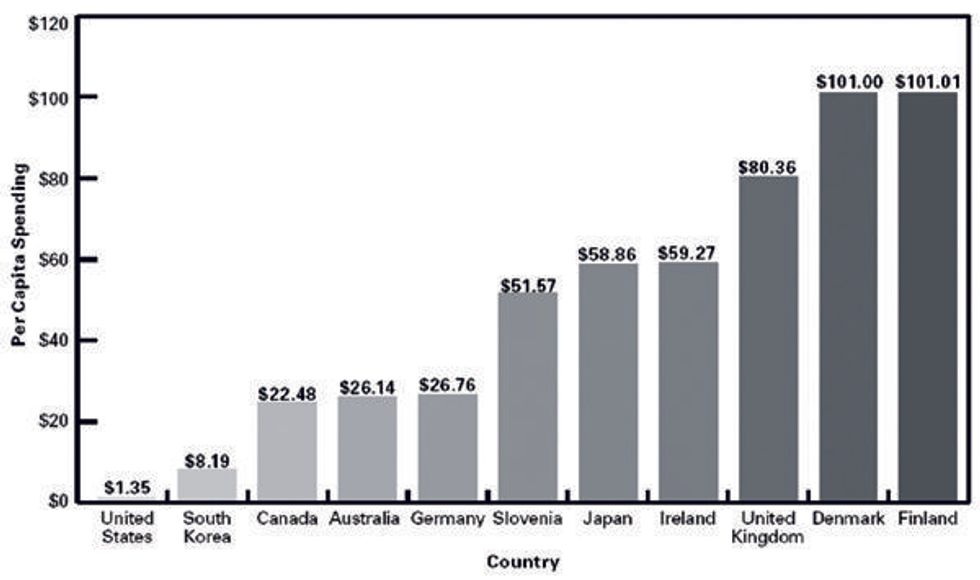

In practice, of course, governments often look out for their own interests, and those of their most powerful supporters. This has been the problem with so-called public broadcasting in the United States, whose promise has gone largely unrealized. Not only is the government funding for PBS and NPR pitifully small in comparison to the support other countries give their public systems (see chart), but the U.S. "public" broadcasters are by design dependent on massive corporate subsidies; with only 40 percent of public broadcasting revenue coming from federal, state or local government (CPB report, 9/09), it's almost impossible to get a show on "noncommercial" television in the United States unless a wealthy for-profit company is willing to buy expensive "underwriting announcements" to air before and after it. (PBS's primary news show, the NewsHour With Jim Lehrer, is mostly owned by the for-profit conglomerate Liberty Media.) And the Corporation for Public Broadcasting, which in theory is supposed to serve as a "heat shield" to protect programmers from political pressures, has in practice been turned into a vehicle for conservatives in Congress to police funding recipients for signs of dangerous ideological independence (Extra! Update, 6/05).

source: Free Press, "Public Media's Moment" Other countries, however, have produced evidence that generous public support for media can produce real results in terms of an informed citizenry. A telling study in the European Journal of Communication (3/09) looking at media systems and public knowledge in four countries-the U.S., Britain, Denmark and Finland-found that the latter two countries, which had the least-commercialized television systems, also featured the most "hard news" programming; these were also the countries with the highest level of knowledge about political affairs, both domestic and international. Particularly striking was the fact that while the United States-and Britain, to a somewhat lesser extent-showed a large gap in political knowledge between college-educated respondents and those with at most a high-school diploma, the Scandinavian countries had a uniformly high level of political awareness across educational classes.

Over the years, many ideas have been put forward about how to invigorate existing U.S. public broadcasting systems-to give them serious and secure funding and remove the levers of political interference that curtail their independence. FAIR (Extra!, 9-10/05) has suggested replacing the Corporation for Public Broadcasting with an independent trust fund that would insulate public broadcasters from partisan pressures. Free Press (5/09) released a white paper called "Public Media's Moment" with a detailed blueprint for improving the funding, governance and diversity of noncommercial broadcasting.

Of course, in a country where offering government health insurance to non-retirees is denounced as socialism, a truly public media system is a hard sell. A single-payer media system isn't the answer; there will always be a need for independent nonprofit journalistic outlets, and even for-profit news can have its place in a diverse information environment. But offering citizens a real public option when it comes to news and debate is an essential part of curing the ills of American democracy.

There have been various proposals to "save journalism" from the crisis brought on by digitalization. But by and large these ideas have less to do with meeting the information needs of a democratic society than with preserving the profit potential of existing media outlets.

Take the various suggestions as to how to get news outlets to stop giving away their content for free. Among others, Walter Isaacson (formerly of Time), Steven Brill (formerly of Content) and Rupert Murdoch (formerly of Australia) have all offered suggestions for how newspapers can be saved by putting their content behind pay walls (Time, 2/5/09; PoynterOnline, 2/9/09; L.A. Times, 8/21/09).

There are several practical difficulties with these proposals. First, if one paper does this and others don't follow suit, readers will likely just migrate to the still-free sites. (This is pretty much why papers like the New York Times and L.A. Times abandoned their experiments with trying to charge for some of their online content-New York Times, 9/18/07.)

But perhaps you could get all the big papers to go in together and create subscriber-only sites all at once. This would run squarely against anti-trust laws, since competitors agreeing to charge more for their product in order to make more money is exactly what anti-trust is supposed to prevent. The solution to this, some have suggested (e.g., Tim Rutten, L.A. Times, 2/4/09), is that newspapers and other corporate news outlets ought to get an anti-trust exemption-though the Obama administration has so far been cool to the idea of approving such a journalistic cartel (Editor & Publisher, 4/22/09).

Even if news outlets were allowed to get together to set prices, of course, they would still have to compete with other websites that offer news. Publishers seem particularly exercised about competition from "aggregators": sites that automatically find and link to news stories found elsewhere, like Google News and parts of Huffington Post. Denouncing these "parasites or tech tapeworms in the intestines of the Internet" (L.A. Times, 8/21/09), corporate journalists have proposed solutions ranging from blocking incoming links to their pages (Newsweek, 9/14/09)-a simple technical fix that no one has tried because it would hurt the publishers worse than aggregators (FAIR Blog, 9/10/09)-to resurrecting the "hot news" doctrine, a 1918 Supreme Court ruling that treated "scoops" as a form of intellectual property (Slate, 4/17/09).

So far, the discussion has centered on whether or not corporate media outlets could overcome these practical and legal hurdles to make more money by restricting their content to paying customers. The more important question, though, is whether this would be a good thing.

At root, the pay-wall proposal is an attempt to turn news into a commodity again, something that people are willing to pay for. Central to the idea of a commodity is scarcity: People pay for things that aren't available to everyone, that they won't benefit from unless they can afford them. The reason there are so many uninsured people in the U.S. is because healthcare is treated as a commodity here-which inevitably means that some people aren't going to get it.

News, we are told, is different from other commodities-since an informed citizenry is essential to democracy-and that's why we need to ignore anti-trust laws to protect it. But it's actually that very importance that makes treating news as a commodity so problematic.

Murdoch's News Corp points to its Wall Street Journal as a success story with its website's 1 million paying customers, and has encouraged the New York Times Co., Washington Post Co., Hearst Corp. and Tribune Co. to follow its lead (L.A. Times, 8/21/09). WSJ.com's success has less to do with offering the paper's news articles and more to do with the company profiles that investors believe will make them money. But imagine that each of those media companies were able to match the Journal's ability to attract paying customers to their own flagship paper's walled-off website.

That would be a total 5 million people with access to the news produced by these companies-or less than 2 percent of the U.S. population. And that's assuming no overlap in their audiences. For comparison purposes, the free New York Times website alone currently has an audience estimated at 20 million.

As it is, it's not like we have a particularly well-informed electorate; if plans for an online news cartel that restricts access to paying subscribers are at all successful, though, today's voters may seem like Encyclopedia Brown.

The status quo, of course-in which the (mostly) free content of the U.S. media system relies on the underwriting of advertisers-is itself far from ideal. Any media system is ultimately going to reflect the interests of the people who foot the bills; it's wishful thinking to imagine you can get giant multinational corporations to pay for a society's informational needs without making sure that the information-gathering system preserves and protects their profits. And that's aside from the direct effects on our collective psyche of advertising itself, a corporate propaganda campaign that spends at least $120 billion annually (Reuters, 9/16/09) in an effort to reshape our thoughts and personalities in a more profitable direction.

If we want news that actually serves the interests of democracy, it can be neither a commodity in itself nor a lure to turn the attention of audiences into a commodity. This means journalism practiced for its own sake, not as a means of making a profit. But how can such journalism be sustainable? In Extra!'s "Future of Journalism" issue (7/09), we described some of the alternative models, including non-profit news outlets subsidized by foundations, and citizen journalism carried out on a largely volunteer basis.

One model we did not discuss is public media-that is, journalism funded by the citizenry via the government. In many ways, it's the obvious solution to the problem of commodity journalism: The state is one of the few institutions whose resources can compare to those of the corporate sector, and at least in theory is supposed to represent the interests of the populace as a whole.

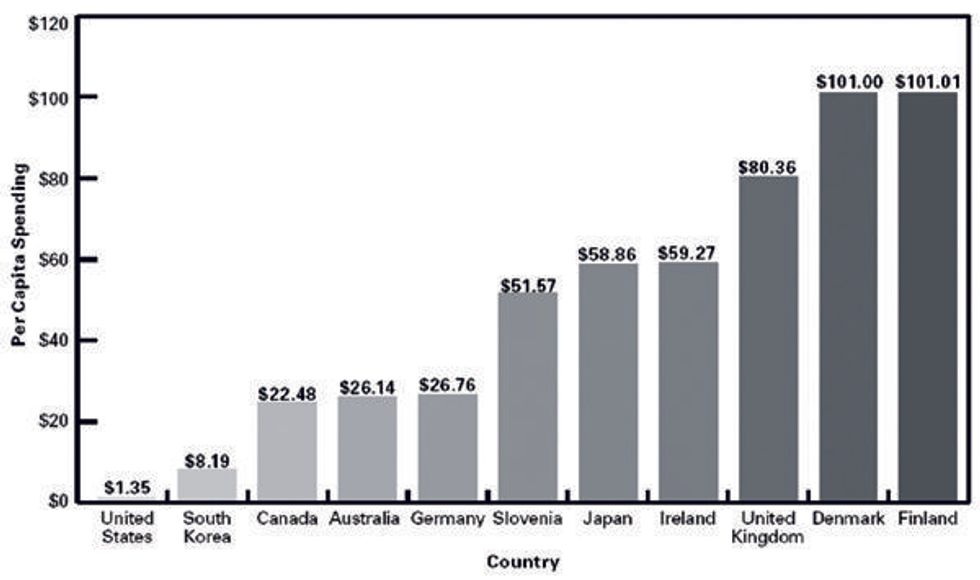

In practice, of course, governments often look out for their own interests, and those of their most powerful supporters. This has been the problem with so-called public broadcasting in the United States, whose promise has gone largely unrealized. Not only is the government funding for PBS and NPR pitifully small in comparison to the support other countries give their public systems (see chart), but the U.S. "public" broadcasters are by design dependent on massive corporate subsidies; with only 40 percent of public broadcasting revenue coming from federal, state or local government (CPB report, 9/09), it's almost impossible to get a show on "noncommercial" television in the United States unless a wealthy for-profit company is willing to buy expensive "underwriting announcements" to air before and after it. (PBS's primary news show, the NewsHour With Jim Lehrer, is mostly owned by the for-profit conglomerate Liberty Media.) And the Corporation for Public Broadcasting, which in theory is supposed to serve as a "heat shield" to protect programmers from political pressures, has in practice been turned into a vehicle for conservatives in Congress to police funding recipients for signs of dangerous ideological independence (Extra! Update, 6/05).

source: Free Press, "Public Media's Moment" Other countries, however, have produced evidence that generous public support for media can produce real results in terms of an informed citizenry. A telling study in the European Journal of Communication (3/09) looking at media systems and public knowledge in four countries-the U.S., Britain, Denmark and Finland-found that the latter two countries, which had the least-commercialized television systems, also featured the most "hard news" programming; these were also the countries with the highest level of knowledge about political affairs, both domestic and international. Particularly striking was the fact that while the United States-and Britain, to a somewhat lesser extent-showed a large gap in political knowledge between college-educated respondents and those with at most a high-school diploma, the Scandinavian countries had a uniformly high level of political awareness across educational classes.

Over the years, many ideas have been put forward about how to invigorate existing U.S. public broadcasting systems-to give them serious and secure funding and remove the levers of political interference that curtail their independence. FAIR (Extra!, 9-10/05) has suggested replacing the Corporation for Public Broadcasting with an independent trust fund that would insulate public broadcasters from partisan pressures. Free Press (5/09) released a white paper called "Public Media's Moment" with a detailed blueprint for improving the funding, governance and diversity of noncommercial broadcasting.

Of course, in a country where offering government health insurance to non-retirees is denounced as socialism, a truly public media system is a hard sell. A single-payer media system isn't the answer; there will always be a need for independent nonprofit journalistic outlets, and even for-profit news can have its place in a diverse information environment. But offering citizens a real public option when it comes to news and debate is an essential part of curing the ills of American democracy.