What are the chances that Trinity will happen again and again, that groups of inventors will gamble the fate of the world again and again, in a world with endless new types of armaments and eternal arms races?

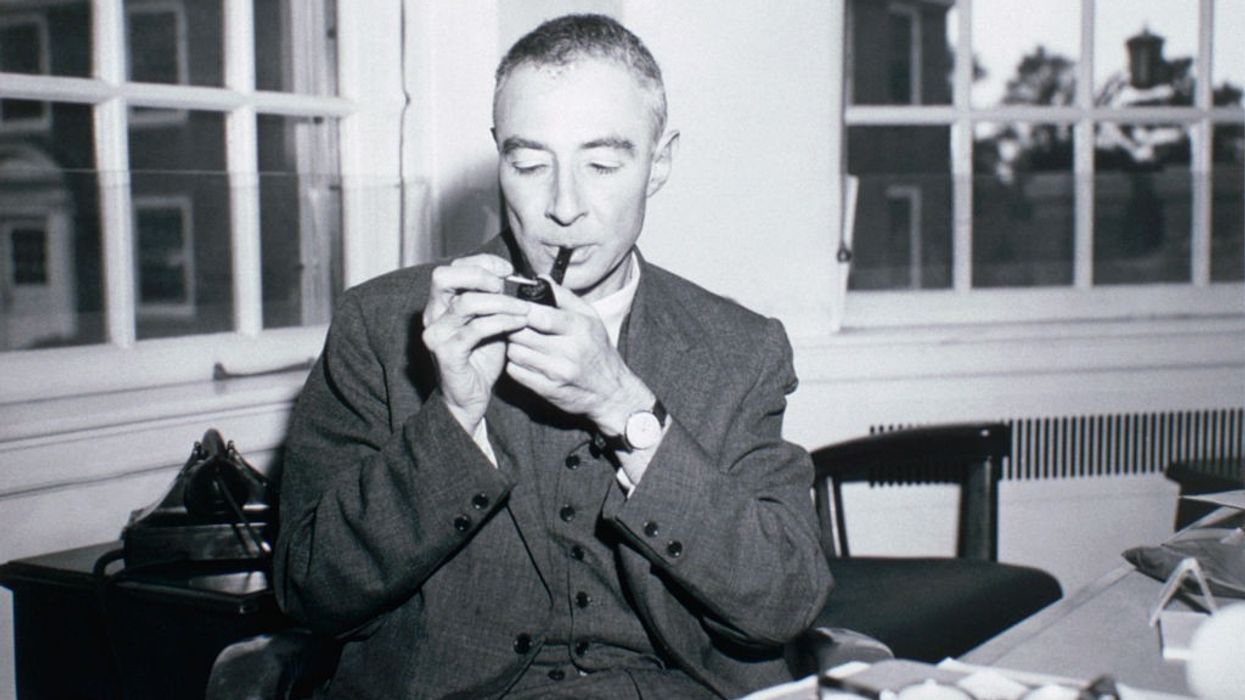

The blockbuster Oppenheimer film won the 2024 Academy Award for Best Picture on Sunday evening March 10th. In perhaps its most chilling scene, Major General Leslie R. Groves, played by Matt Damon, implores Dr. Oppenheimer, played by Cillian Murphy, to reassure him that there was no possibility that “when we push that button, we destroy the world.” “The chances are near zero,” Oppenheimer replies, rather blithely. Groves’s eyes widen. A look of incredulity appears on his face. “Near zero?” “What do you expect from theory alone?” asks Oppenheimer. “Zero,” says the general in exasperation, “would be nice.”

It Didn't Happen Then, But It May Happen Someday

The real story behind this fictional exchange is, yes, infinitely more terrifying. And it bodes very ill indeed for the future of the human race and life on Earth. Because in the absence of a supranational global authority, in a world caught up instead in what we might call a “forever arms race,” this scenario will surely happen again. Albert Einstein made this point only a month after Nagasaki and Hiroshima. “As long as nations demand unrestricted sovereignty,” he said, “we shall undoubtedly be faced with still bigger wars, fought with bigger and technologically more advanced weapons.” Laser weapons, space weapons, cyber weapons, nano weapons, bio weapons. Fast forward just a few decades, and one cannot even envisage the new adjectives in front of the ancient noun. Perhaps most ominously, consider the arms race already underway to develop artificially-intelligent semi-autonomous robot weapons. While artificial general intelligence is unlikely to destroy the world in a quick flash, the existential threat it poses to humanity (intentionally weaponized or otherwise) is today on everyone’s mind.

And one day, the dice will roll badly. The gamble will go wrong. And then the game will be over forever.

Edward Teller Identified the Scenario and No One Could Convince Everyone to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb

This episode, where rational human beings undertook an action even though they believed there was a non-zero possibility that it would bring an abrupt end to all life on Earth, began at a meeting of scientists at UC Berkeley on July 7, 1942. Edward Teller was the first to suggest it. He informed his colleagues that the heat produced by the fission reaction they were planning to generate might, repeat might, ignite a fusion reaction in both the hydrogen and deuterium in our single world ocean, and the nitrogen in Earth’s atmosphere. In an instant, intense temperatures hotter than the sun would immediately extinguish every living thing on Earth. And that would be that.

For the next three years, the leading scientists of the Manhattan Project argued stridently about whether or not this quintessentially apocalyptic event might take place. Everyone seemed to agree that it was extremely unlikely. But no one could get everyone to agree that it was impossible.

The official historian of the Manhattan Project, David Hawkins, said in 1982 that he conducted more interviews with the Manhattan scientists on this topic than on anything else. He said: “Younger researchers kept rediscovering the possibility, from start to finish of the project.” And Hawkins concluded from these conversations that despite an endless number of theoretical calculations, they never managed to confirm with mathematical certainty that setting the world ablaze with a single atomic detonation would definitely not occur.

Hans Bethe insisted that the ignition of the oceans and the atmosphere was “impossible.” But Enrico Fermi was never fully convinced. According to Peter Goodchild, who produced a superb TV miniseries about Oppenheimer in 1980 starring Sam Waterston, Fermi – in the true Socratic fashion of recognizing what he did not know – “worried whether there were undiscovered phenomena that, under the novel conditions of extreme heat, might lead to unexpected disaster.” And on the long drive from Los Alamos to Alamogordo for the Trinity test, Fermi (presumably facetiously) told a companion: “It would be a miracle if the atmosphere were ignited. I reckon the chance of a miracle to be about ten percent.”

The scientists in the film are shown placing bets on whether the Trinity test would unleash that fusion reaction upon the entire globe. (How those who put their money down on the affirmative planned to collect, if they had “won,” was not made entirely clear.) Scientist James B. Conant, who had resigned as the president of Harvard University to become head of the National Defense Research Committee -- and the de facto boss of both Oppenheimer and Groves -- recounted his own Trinity experience years later. Conant said that at the moment of detonation, he was most surprised by the duration of the light. It wasn’t a quick bright burst like a camera flash, but persisted for seconds. And what did that lead him to fear? “My instantaneous reaction was that something had gone wrong, and that the thermal nuclear transformation of the atmosphere, once discussed as a possibility and jokingly referred to a few minutes earlier, had actually occurred.”

Daniel Ellsberg, who wrote elaborately about this Manhattan Project dilemma in his masterful 2017 book The Doomsday Machine: Confessions of a Nuclear War Planner, drew the same conclusion: “The Manhattan Project did continue, at full blast (so to speak), but not because further calculations and partial tests proved beyond doubt that there was no possibility of … atmospheric ignition. … No one, including Bethe, was able to convince most others that the ultimate catastrophe was ‘not possible’ … Most of the senior theorists did believe the chance was very small, but not zero.”

They Pushed the Button

But the Manhattan scientists, nonetheless, went ahead. They set off history’s first atomic detonation. They took a chance, however remote, on ending everything. Because of the pressure to end the war, because of the demands of military competition with adversaries present (Japan) and prospective (the Soviet Union), and surely to some extent because of concern for their own positions (“We gave you three years and $2.2 billion and now you want to call the whole thing off?”), they took it upon themselves to gamble the fate of the world.

And perhaps the most disturbing part of this story is who made the decision to take the risk. Because it wasn’t “the American government.” It wasn’t the elected officials of our representative democracy. It wasn’t President Harry S. Truman. Even though the scientists, for three long years, discussed among themselves “the odds” that they might bring about the sudden and fiery end of the world, there is no record, none, that they ever brought their dilemma to the attention of any political authorities. Or even General Groves! In the film, Oppenheimer talks to Einstein about it. But no one ever talked to any democratically-elected political leaders about it.

There are some who dispute whether the Manhattan scientists really did make this choice. “This thing has been blown out of proportion over the years. They knew what they were doing. They were not feeling around in the dark,” says Richard Rhodes, author of the Pulitzer Prize-winning book The Making of the Atomic Bomb. “What a physicist means by ‘near zero’ would be zero to an engineer,” says Aditi Verma, an assistant professor of nuclear engineering and radiological sciences at the University of Michigan.

But the point for us to contemplate for the human future is that human beings can make this choice. Consider, for example, how much more pressure the Manhattan scientists would have felt if the atom bomb had been ready to go sooner. Germany was already vanquished by July 1945, and Japan very nearly so. But when the project began three years earlier, there seemed to the protagonists a quite real possibility that Germany might invent an atom bomb first. What if there was, say, a one in a million chance that pressing the button would incinerate all of creation, but a vastly greater likelihood that failing to press the button would lead to Hitler incinerating American cities?

And Yes, The Stakes Are Truly Infinite

During my time at the Pardee RAND Graduate School and the RAND Corporation – where many of the strategic nuclear doctrines of the Cold War originally were forged -- I was taught that the best way to conceptualize “risk” was the probability of a hypothetical event multiplied by the magnitude of its consequences. (And yes, no one could resist calling those of us training to be nuclear use theorists “the NUTs.”)

But even if it wasn’t anywhere near that 10% figure that Fermi tossed out there (doubtless in jest), what is, oh, 0.0001% times infinity? Because the Manhattan scientists took it upon themselves to “risk” ending the existence not only of every living thing on Planet Earth on July 16, 1945, but also all of us born later, destined never to exist if their wager had gone wrong. An infinity of future lives, human and otherwise. The greatest imaginable crime against humanity, and upon the whole circle of life on Earth.

And too, it may be the case, perhaps not likely but assuredly not impossible, that we Earthlings are alone, in all of space and time, past, present, and future. After all, it was that same Enrico Fermi, at a Manhattan Project lunch table, who ostensibly posed his famous “paradox.” If the universe is teeming with extraterrestrial intelligence, he asserted, by now they would have had plenty of time to spread almost everywhere (with self-replicating autonomous robots if not biological beings). So where are they?

Paleobiologists know very little about the origins of life, and most especially, the frequency or rarity of whatever happened on our lonely blue planet 3.5 billion years ago. The emergence of life, or its elaboration into sentient life, may be something that takes place quite frequently on planets where the conditions are right. Or it may be instead something that happens only once in a trillion trillion trillion times. We homo sapiens may, repeat may, be the only beings smart enough, anywhere and ever, to create a social and cultural and technological civilization, to contemplate the nature of the universe, and perhaps one day to fill it with our descendants.

And yet a tiny handful of those human beings took it upon themselves to take the chance, however infinitesimal they might have assessed it to be, of bringing this (possibly) unique single blossom of intelligence to an abrupt and sudden end. Perhaps then we might say that they risked committing not only an infinite crime against an infinite future, but upon the entirety of the universe as well.

The Logic of Anarchy Prevails

“I believe that our Great Maker is preparing the world … to become one nation,” said U.S. President Ulysses S. Grant during his second inaugural address in 1873, “when armies and navies will be no longer required.” But until the dawn of that day, separate sovereign nations will be forced to compete with each other eternally, to keep up with each other in the latest in weapons technology. As soon as any kind of new weapon gets invented? The great military powers feel irresistibly compelled to develop it and to deploy it. Because if they don’t, their adversaries will.

This dynamic is called “the security dilemma” by international relations theorists. “Because any state may at any time use force, all states must constantly be ready either to counter force with force or to pay the cost of weakness,” said one of the pioneers of that academic discipline, Professor Kenneth Waltz of Berkeley and Columbia, in his classic Man, The State, and War of 1954. Karl von Clausewitz advanced the same argument in his On War of 1832 – sounding a bit like Isaac Newton. “Each of the adversaries forces the hand of the other, and a reciprocal action results which in theory can have no limit … So long as I have not overthrown my adversary I must fear that he may overthrow me. I am no longer my own master. He forces my hand as I force his.” The Native American political humorist Will Rogers put it more severely in 1929. “You can’t say humanity don’t advance. In every war, they kill you in a new way.”

Forever Would Be Nice

There are many other reasons to lament this eternal competition in developing new instruments of annihilation, of course, besides the prospect that the testing of new weapons will go maximally awry. There is the permanent necessity for groups of humans to devote vast quantities of both toil and treasure to “defending themselves” against other groups of humans – when those resources could do so much to improve the lives of the humans within those groups instead. And if history is any guide there’s the virtual certainty, every few decades or so, that perpetual preparation for war degenerates into actual war – with ever more cataclysmic arsenals of doom.

So what are the chances that Trinity will happen again and again, that groups of inventors will gamble the fate of the world again and again, in a world with endless new types of armaments and eternal arms races? What are the chances that we can roll these dice, time and time again, before the atmosphere and the oceans do instantaneously ignite, or before who knows what other apocalyptic scenario -- in the spirit of Enrico Fermi utterly unknown to us today -- will bring about the end of the world tomorrow? What are the odds that our fair species can survive indefinitely if we remain perpetually divided into tribes with clubs, and if every generation or so scientists face the same excruciating choice as J. Robert Oppenheimer faced on July 16, 1945, solely because they cannot escape the inexorable obligation to build bigger and better clubs?

The chances are near zero.