With Troop Deployments in US Cities, Trump Has Picked a Fight With the Constitution

He wants the US Supreme Court to legitimatize these unlawful deployments. Heaven help us all if they do.

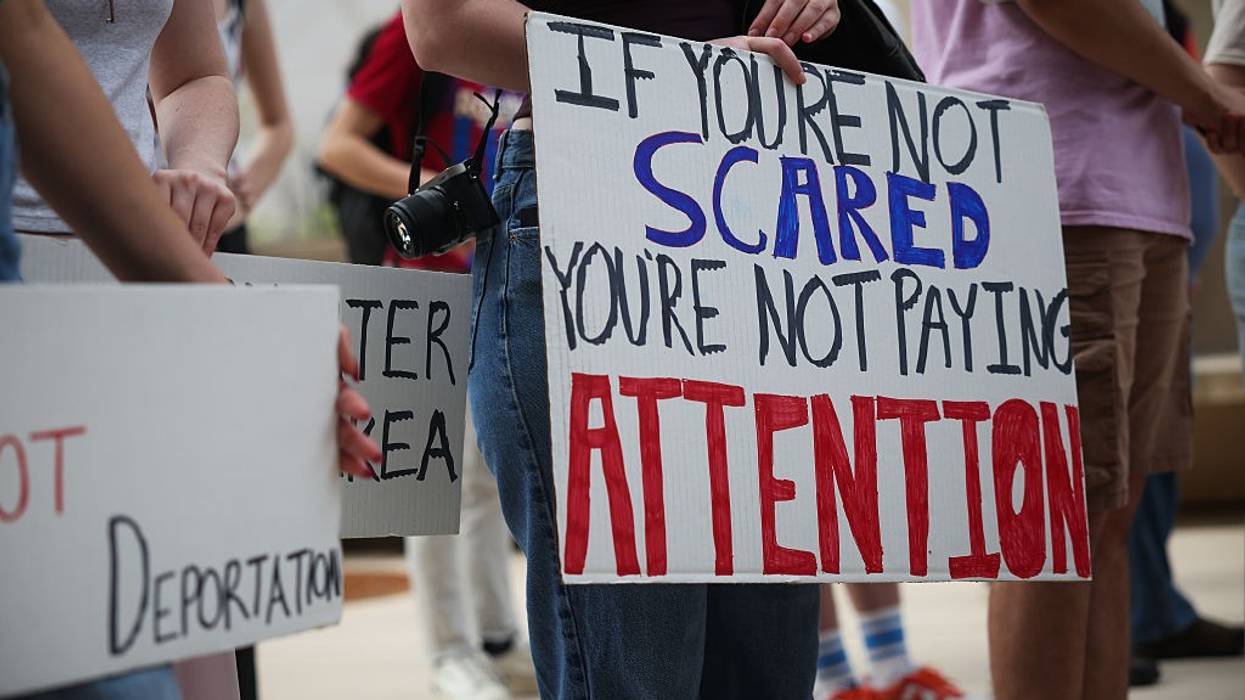

President Donald Trump’s ICE raids in American cities are not simply efforts to deport undocumented immigrants or battle crime. In addition to creating fear and desensitizing law-abiding citizens to a military presence on American streets, Trump wanted to pick a fight.

And he has.

Specifically, Trump wanted a legal fight that he could take to the conservative majority on the US Supreme Court. If it accepts his justification for “federalizing” the National Guard over a state governor’s objections, he’ll have unrestrained power to deploy the military on American soil any time, any place, and for any reason.

The implications are staggering. Fear has gripped neighborhoods where armed troops patrol the streets as something akin to an occupying force. During the 2026 midterm elections, deployments would be a powerful voter suppression tool.

Trump’s Legal Argument

In the cases challenging Trump’s National Guard deployments in Los Angeles, Portland, and Chicago, his lawyers have argued that the courts have no power to review the President’s decisions. His claimed factual basis is not subject to challenge. His decision is final. His authority is absolute.

Trump bases his argument on language in an 1827 case involving Jacob Mott, a state militiaman. Mott refused to report for duty when President James Madison called up the New York militia during the War of 1812. The Supreme Court ruled that Mott had no right to dispute the president’s judgment.

Trump has appealed to the Supreme Court, where the conservative majority has a track record of giving Trump anything he wants.

Extrapolating the language of that case involving a subordinate militiaman during a time of war to foreclose all judicial review of the factual basis for Trump’s deployments is a stretch. But one appellate court judge in the ongoing ICE cases has embraced Trump’s position.

California

In June, Trump mobilized the National Guard over the objections of Gov. Gavin Newsom (D-Calif). The president invoked the statute authorizing him to “federalize” the Guard, which permits such action only if:

(1) theUnited States, or any of the Commonwealths or possessions, is invaded or is in danger of invasion by a foreign nation;

(2) there is a rebellion or danger of a rebellion against the authority of the Government of the United States; or

(3) the President is unable with the regular forces to execute the laws of the United States.” (10 U.S.C. Sec. 12406)

Trump claimed that the factual circumstances entitled him to invoke subsections (2) and (3).

The trial court granted Newsom’s request for a temporary restraining order, and the Trump administration appealed. Trump’s primary argument was that he had unrestrained discretion to make the required statutory determinations (i.e., whether there was a rebellion, danger or rebellion, or inability with regular forces to execute federal law). Whatever he decided should be the beginning and the end of the inquiry. Actual facts contradicting his claims were out of bounds. Judges couldn’t scrutinize his justifications. No one could.

The Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals (including two Trump appointees on the three-judge panel) rejected Trump’s argument. The court ruled that the president’s power is not absolute, but he is entitled to “a great level of deference” in making the required factual determinations.

Portland

When Trump deployed troops in Portland, Oregon, the city and the state sued to block him, and he made the same argument. Federal District Court Judge Karin Immergut—a Trump appointee—followed the appellate court’s earlier California decision and rejected it.

Judge Immergut’s 31-page opinion set forth her factual findings and legal conclusions. She outlined the evidence that rebutted Trump’s claimed “facts.” The court acknowledged that “the President is certainly entitled ‘a great level of deference’... But ‘a great level of deference’ is not equivalent to ignoring the facts on the ground… The President’s determination was simply untethered to the facts.”

Judge Immergut granted the motion to prevent the deployment.

Reversed on Appeal

Under well-settled law, Judge Immergut’s ruling could be reversed on appeal only if it was an “abuse of discretion”—which it wasn’t. The appellate court had to accept her factual findings as true, unless they were “clearly erroneous”—which they weren’t.

But in a two-to-one vote, the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals reversed Judge Immergut’s ruling. Rather than respect the trial court’s detailed factual findings, the Trump-appointed majority discarded them in favor of its own characterization of the record.

Ironically, the court concluded, “[T]he district court erred by placing too much weight on statements the President made on social media.”

Judge Ryan Nelson—one of two judges comprising the majority that reversed Judge Immergut—accepted Trump’s primary argument. In his concurring opinion Judge Nelson wrote that “the President’s decision in this area is absolute.”

Facts and evidence don’t matter. Everyone has to take Trump at his word—a remarkable empowerment of a serial liar.

The dissenting opinion of Judge Susan Graber, a Clinton appointee, returned to the facts:

Given Portland protesters’ well-known penchant for wearing chicken suits, inflatable frog costumes, or nothing at all when expressing their disagreement with the methods employed by ICE, observers may be tempted to view the majority’s ruling, which accepts the government’s characterization of Portland as a war zone, as merely absurd. But today’s decision is not merely absurd. It erodes core constitutional principles, including sovereign States’ control over their States’ militias and the people’s First Amendment rights to assemble and to object to the government’s policies and actions.

Judge Graber pleaded for additional scrutiny of the majority’s errant decision:

By design of the Founders, the judicial branch stands apart. We rule on facts, not on supposition or conjecture, and certainly not on fabrication or propaganda. I urge my colleagues on this court to act swiftly to vacate the majority’s order before the illegal deployment of troops under false pretenses can occur.

That process—a request for en banc review by 11 randomly-selected judges in the Ninth Circuit—is underway.

Chicago

Meanwhile, the Seventh Circuit Court of Appeals affirmed unanimously a trial judge’s order blocking Trump’s deployment of the National Guard in Chicago. As in Los Angeles and Portland, Trump argued that the courts had no role in reviewing his factual determinations. The court—including a George H. W. Bush appointee, a George W. Bush appointee, and an Obama appointee—rejected Trump’s argument.

Unlike the majority in the Portland appeal, the court accepted the lower court’s factual findings and applied them:

Political opposition is not rebellion. A protest does not become a rebellion merely because the protestors advocate for myriad legal or policy changes, are well organized, call for significant changes to the structure of the US government, use civil disobedience as a form of protest, or exercise their Second Amendment right to carry firearms as the law currently allows.

Nor did the activity surrounding the ICE facility render federal officers incapable of executing the laws of the United States.

Trump has appealed to the Supreme Court, where the conservative majority has a track record of giving Trump anything he wants. As of September 22, he had won 21 cases on the Court’s “shadow docket” where little or no reasoning accompanied quick decisions granted on a “preliminary” basis (even though the impact often was profound and enduring). His administration had lost only two, with two others pending. Two were withdrawn and was one dismissed.

In asking the Supreme Court to intervene, Trump’s lawyers called the Seventh Circuit’s ruling part of a “disturbing and recurring pattern” that “improperly impinges on the President’s authority and needlessly endangers federal personnel and property.”

None of that is true. The only “disturbing and recurring pattern” is Trump’s false assertions to justify deploying the military on American soil. And now he wants to prevent anyone challenging him—ever.