SUBSCRIBE TO OUR FREE NEWSLETTER

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

5

#000000

#FFFFFF

To donate by check, phone, or other method, see our More Ways to Give page.

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

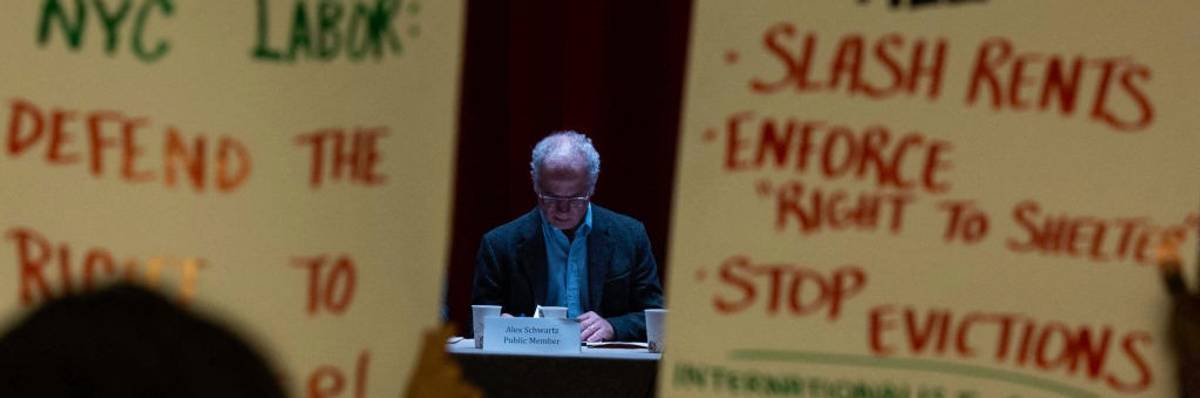

Tenants and housing activists protest at Hunter College where a vote took place to raise rent for roughly 2 million New Yorkers in New York on June 21, 2023. Rent-stabilized apartments will see an increase for the second year in a row despite being a lifeline for many New Yorkers.

'Our state and local governments together operate a massive, ruthlessly efficient collection and repossession machine for the benefit of landlords'

As we see in the packed Indianapolis courtrooms where my law students and I represent low-income tenants each week, evictions across the country are rising. Census figures show nearly eight million households are behind on their rent, teetering on the edge of joining those who line up to hear what day a judge orders them to move. With these evictions comes huge and often irreversible damage to families’ finances and physical and mental health.

The chief driver of this crisis is our nation’s appalling shortage of affordable housing. Tenants and other activists rightly push forward plans for expanded public housing, housing vouchers for all who are eligible, and rent control. But we should not neglect an immediate, obvious remedy: stop evicting so many people.

It really can be that simple. Our state and local governments together operate a massive, ruthlessly efficient collection and repossession machine for the benefit of landlords, particularly corporate landlords. We the people run this machine, so we can decide to pump the brakes.

Consider my home state of Indiana, which has one of the nation's highest eviction rates. That is in large part because our lawmakers and courts have chosen to make evictions remarkably fast, cheap, and easy. Fast: tenants can be ordered out of their homes as quickly as ten days after a case is filed. Cheap: it costs as little as $104 for a landlord to file an eviction case. And easy: Most tenants here don’t have lawyers, most judges here tell tenants that even egregiously unsafe conditions are not an excuse for non-payment of rent, and our state does not require a landlord to have good cause for evicting a tenant.

Nearly all states make eviction filing a snap, as sociologist and Evicted author Matthew Desmond and colleagues found in an analysis of eight million court records from dozens of jurisdictions across the country. They found that low fees and lax procedures caused courts to, in their words, “act more like an extension of the residential rental business than an impartial arbitrator between landlords and tenants.”

The top beneficiaries of courts’ eviction mills are the ever-expanding institutional, aka corporate, landlords that have built an increasingly dominant presence in communities across the country. These mega-companies file for eviction much more quickly than the vanishing breed of mom-and-pop landlords. For example, Indianapolis Star analysis of the 2021 eviction filings in our community showed that 88% of the cases were initiated by corporate landlords. Surveys show landlords are well aware of the advantage our justice system gives them, so they eagerly use the courts to jump the line in front of tenants’ competing obligations like utilities, food, and healthcare.

Our governments should not be providing landlords with VIP access to court orders and police muscle that other litigants don’t have access to. When people turn to our civil courts to seek payment of a debt, dissolution of a marriage, or resolution of an estate, they wait months if not years for a court order. We can make evictions less fast, cheap, and easy just by holding landlords to the same standards that other litigants must meet.

For example, our county’s local courts require mandatory mediation for parties who seek civil jury trials, post-divorce-decree rulings, or two hours or more of court time for contested family law hearings. In our state’s foreclosure cases, settlement conferences are mandatory. Applying similar rules to eviction cases would put an end to the current phenomenon of landlords rushing to court for a “gotcha” filing, sometimes within days of a tenant being late on rent.

The change would make a big difference: anyone working with struggling tenants can tell you that a little additional time is often precious. Even an extra week or two before an eviction case is filed or heard in court could be the time needed for another paycheck or a tax refund to arrive, or a relative or social service agency to come through with the rent owed, any one of which can prevent a renting family from becoming homeless.

Many landlords admit they regularly uses the court eviction process to shake down tenants for late rent rather than to truly seek possession of the rental property. The fix here is obvious: raise the court filing fees substantially. If our governments are going to operate a for-hire collection and enforcement apparatus, let’s at least make it less of a bargain.

Finally, we can reduce evictions by requiring landlords to clear some of the same kind of procedural hurdles that other court litigants must navigate. We should protect tenants by requiring a landlord to show good cause for refusing to renew their leases. We should adopt “clean hands” requirements to block landlords with housing code violations from evicting tenants.

Since we control the eviction machine, we can even decide to shut it down during times of health, economic, or weather emergencies. We proved this option works when the U.S. Centers for Disease Control’s Covid-triggered eviction moratorium prevented 1.5 million evictions, saving families and communities untold disease spread and suffering.

To enforce these additional legal protections for tenants, we need to fix the fact that 90% of tenants go to eviction court without an attorney, while landlords virtually always have a lawyer. When the very roof over a family’s head is at stake, all communities need to follow the lead of the cities that have ensured tenants have a lawyer by their side.

Those lawyers, along with new rules slowing down the process and making evictions the exception rather than the norm, would ensure that the due process of law finally applies to tenants as well as landlords. Which would go a long way toward pumping the brakes on our runaway government eviction machine.

Originally published in The Hill

Dear Common Dreams reader, The U.S. is on a fast track to authoritarianism like nothing I've ever seen. Meanwhile, corporate news outlets are utterly capitulating to Trump, twisting their coverage to avoid drawing his ire while lining up to stuff cash in his pockets. That's why I believe that Common Dreams is doing the best and most consequential reporting that we've ever done. Our small but mighty team is a progressive reporting powerhouse, covering the news every day that the corporate media never will. Our mission has always been simple: To inform. To inspire. And to ignite change for the common good. Now here's the key piece that I want all our readers to understand: None of this would be possible without your financial support. That's not just some fundraising cliche. It's the absolute and literal truth. We don't accept corporate advertising and never will. We don't have a paywall because we don't think people should be blocked from critical news based on their ability to pay. Everything we do is funded by the donations of readers like you. Will you donate now to help power the nonprofit, independent reporting of Common Dreams? Thank you for being a vital member of our community. Together, we can keep independent journalism alive when it’s needed most. - Craig Brown, Co-founder |

As we see in the packed Indianapolis courtrooms where my law students and I represent low-income tenants each week, evictions across the country are rising. Census figures show nearly eight million households are behind on their rent, teetering on the edge of joining those who line up to hear what day a judge orders them to move. With these evictions comes huge and often irreversible damage to families’ finances and physical and mental health.

The chief driver of this crisis is our nation’s appalling shortage of affordable housing. Tenants and other activists rightly push forward plans for expanded public housing, housing vouchers for all who are eligible, and rent control. But we should not neglect an immediate, obvious remedy: stop evicting so many people.

It really can be that simple. Our state and local governments together operate a massive, ruthlessly efficient collection and repossession machine for the benefit of landlords, particularly corporate landlords. We the people run this machine, so we can decide to pump the brakes.

Consider my home state of Indiana, which has one of the nation's highest eviction rates. That is in large part because our lawmakers and courts have chosen to make evictions remarkably fast, cheap, and easy. Fast: tenants can be ordered out of their homes as quickly as ten days after a case is filed. Cheap: it costs as little as $104 for a landlord to file an eviction case. And easy: Most tenants here don’t have lawyers, most judges here tell tenants that even egregiously unsafe conditions are not an excuse for non-payment of rent, and our state does not require a landlord to have good cause for evicting a tenant.

Nearly all states make eviction filing a snap, as sociologist and Evicted author Matthew Desmond and colleagues found in an analysis of eight million court records from dozens of jurisdictions across the country. They found that low fees and lax procedures caused courts to, in their words, “act more like an extension of the residential rental business than an impartial arbitrator between landlords and tenants.”

The top beneficiaries of courts’ eviction mills are the ever-expanding institutional, aka corporate, landlords that have built an increasingly dominant presence in communities across the country. These mega-companies file for eviction much more quickly than the vanishing breed of mom-and-pop landlords. For example, Indianapolis Star analysis of the 2021 eviction filings in our community showed that 88% of the cases were initiated by corporate landlords. Surveys show landlords are well aware of the advantage our justice system gives them, so they eagerly use the courts to jump the line in front of tenants’ competing obligations like utilities, food, and healthcare.

Our governments should not be providing landlords with VIP access to court orders and police muscle that other litigants don’t have access to. When people turn to our civil courts to seek payment of a debt, dissolution of a marriage, or resolution of an estate, they wait months if not years for a court order. We can make evictions less fast, cheap, and easy just by holding landlords to the same standards that other litigants must meet.

For example, our county’s local courts require mandatory mediation for parties who seek civil jury trials, post-divorce-decree rulings, or two hours or more of court time for contested family law hearings. In our state’s foreclosure cases, settlement conferences are mandatory. Applying similar rules to eviction cases would put an end to the current phenomenon of landlords rushing to court for a “gotcha” filing, sometimes within days of a tenant being late on rent.

The change would make a big difference: anyone working with struggling tenants can tell you that a little additional time is often precious. Even an extra week or two before an eviction case is filed or heard in court could be the time needed for another paycheck or a tax refund to arrive, or a relative or social service agency to come through with the rent owed, any one of which can prevent a renting family from becoming homeless.

Many landlords admit they regularly uses the court eviction process to shake down tenants for late rent rather than to truly seek possession of the rental property. The fix here is obvious: raise the court filing fees substantially. If our governments are going to operate a for-hire collection and enforcement apparatus, let’s at least make it less of a bargain.

Finally, we can reduce evictions by requiring landlords to clear some of the same kind of procedural hurdles that other court litigants must navigate. We should protect tenants by requiring a landlord to show good cause for refusing to renew their leases. We should adopt “clean hands” requirements to block landlords with housing code violations from evicting tenants.

Since we control the eviction machine, we can even decide to shut it down during times of health, economic, or weather emergencies. We proved this option works when the U.S. Centers for Disease Control’s Covid-triggered eviction moratorium prevented 1.5 million evictions, saving families and communities untold disease spread and suffering.

To enforce these additional legal protections for tenants, we need to fix the fact that 90% of tenants go to eviction court without an attorney, while landlords virtually always have a lawyer. When the very roof over a family’s head is at stake, all communities need to follow the lead of the cities that have ensured tenants have a lawyer by their side.

Those lawyers, along with new rules slowing down the process and making evictions the exception rather than the norm, would ensure that the due process of law finally applies to tenants as well as landlords. Which would go a long way toward pumping the brakes on our runaway government eviction machine.

Originally published in The Hill

As we see in the packed Indianapolis courtrooms where my law students and I represent low-income tenants each week, evictions across the country are rising. Census figures show nearly eight million households are behind on their rent, teetering on the edge of joining those who line up to hear what day a judge orders them to move. With these evictions comes huge and often irreversible damage to families’ finances and physical and mental health.

The chief driver of this crisis is our nation’s appalling shortage of affordable housing. Tenants and other activists rightly push forward plans for expanded public housing, housing vouchers for all who are eligible, and rent control. But we should not neglect an immediate, obvious remedy: stop evicting so many people.

It really can be that simple. Our state and local governments together operate a massive, ruthlessly efficient collection and repossession machine for the benefit of landlords, particularly corporate landlords. We the people run this machine, so we can decide to pump the brakes.

Consider my home state of Indiana, which has one of the nation's highest eviction rates. That is in large part because our lawmakers and courts have chosen to make evictions remarkably fast, cheap, and easy. Fast: tenants can be ordered out of their homes as quickly as ten days after a case is filed. Cheap: it costs as little as $104 for a landlord to file an eviction case. And easy: Most tenants here don’t have lawyers, most judges here tell tenants that even egregiously unsafe conditions are not an excuse for non-payment of rent, and our state does not require a landlord to have good cause for evicting a tenant.

Nearly all states make eviction filing a snap, as sociologist and Evicted author Matthew Desmond and colleagues found in an analysis of eight million court records from dozens of jurisdictions across the country. They found that low fees and lax procedures caused courts to, in their words, “act more like an extension of the residential rental business than an impartial arbitrator between landlords and tenants.”

The top beneficiaries of courts’ eviction mills are the ever-expanding institutional, aka corporate, landlords that have built an increasingly dominant presence in communities across the country. These mega-companies file for eviction much more quickly than the vanishing breed of mom-and-pop landlords. For example, Indianapolis Star analysis of the 2021 eviction filings in our community showed that 88% of the cases were initiated by corporate landlords. Surveys show landlords are well aware of the advantage our justice system gives them, so they eagerly use the courts to jump the line in front of tenants’ competing obligations like utilities, food, and healthcare.

Our governments should not be providing landlords with VIP access to court orders and police muscle that other litigants don’t have access to. When people turn to our civil courts to seek payment of a debt, dissolution of a marriage, or resolution of an estate, they wait months if not years for a court order. We can make evictions less fast, cheap, and easy just by holding landlords to the same standards that other litigants must meet.

For example, our county’s local courts require mandatory mediation for parties who seek civil jury trials, post-divorce-decree rulings, or two hours or more of court time for contested family law hearings. In our state’s foreclosure cases, settlement conferences are mandatory. Applying similar rules to eviction cases would put an end to the current phenomenon of landlords rushing to court for a “gotcha” filing, sometimes within days of a tenant being late on rent.

The change would make a big difference: anyone working with struggling tenants can tell you that a little additional time is often precious. Even an extra week or two before an eviction case is filed or heard in court could be the time needed for another paycheck or a tax refund to arrive, or a relative or social service agency to come through with the rent owed, any one of which can prevent a renting family from becoming homeless.

Many landlords admit they regularly uses the court eviction process to shake down tenants for late rent rather than to truly seek possession of the rental property. The fix here is obvious: raise the court filing fees substantially. If our governments are going to operate a for-hire collection and enforcement apparatus, let’s at least make it less of a bargain.

Finally, we can reduce evictions by requiring landlords to clear some of the same kind of procedural hurdles that other court litigants must navigate. We should protect tenants by requiring a landlord to show good cause for refusing to renew their leases. We should adopt “clean hands” requirements to block landlords with housing code violations from evicting tenants.

Since we control the eviction machine, we can even decide to shut it down during times of health, economic, or weather emergencies. We proved this option works when the U.S. Centers for Disease Control’s Covid-triggered eviction moratorium prevented 1.5 million evictions, saving families and communities untold disease spread and suffering.

To enforce these additional legal protections for tenants, we need to fix the fact that 90% of tenants go to eviction court without an attorney, while landlords virtually always have a lawyer. When the very roof over a family’s head is at stake, all communities need to follow the lead of the cities that have ensured tenants have a lawyer by their side.

Those lawyers, along with new rules slowing down the process and making evictions the exception rather than the norm, would ensure that the due process of law finally applies to tenants as well as landlords. Which would go a long way toward pumping the brakes on our runaway government eviction machine.

Originally published in The Hill