SUBSCRIBE TO OUR FREE NEWSLETTER

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

5

#000000

#FFFFFF

To donate by check, phone, or other method, see our More Ways to Give page.

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

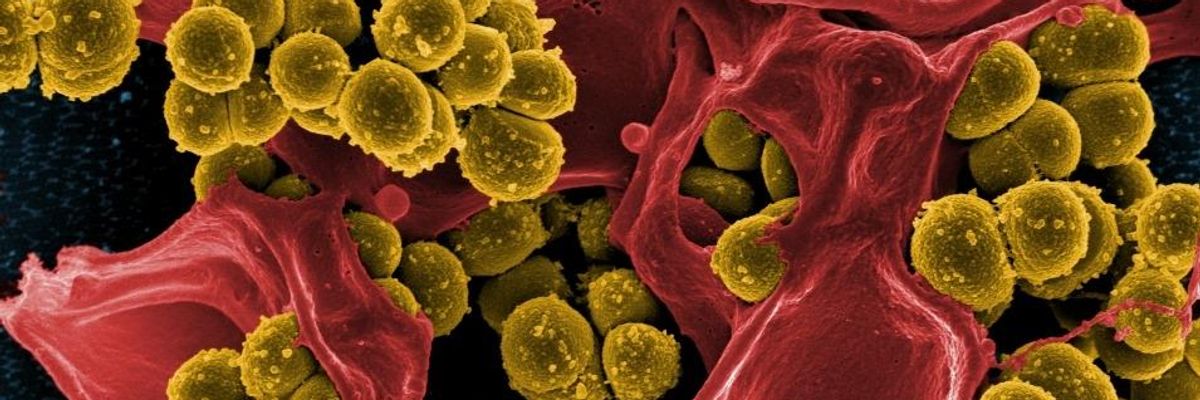

Micrograph of Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) (Photo: NIAID)

Adding to mounting concerns about widespread antibiotic resistance, U.S. public health officials detected more than 220 cases of what they described as "nightmare bacteria" across more than half the country last year, according to a new government report.

In just nine months of surveillance during 2017, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) found "nightmare bacteria" with "unusual" resistance in 27 states, fueling the agency's warnings that "antibiotic-resistant germs can spread like wildfire."

The CDC considers antibiotic-resistant germs "unusual" if they are: resistant to all or most antibiotics; uncommon in a geographic area or the U.S.; or have genes that allow them to spread their resistance to other germs.

These "dangerous pathogens, hiding in plain sight...can cause infections that are difficult or impossible to treat," explained CDC principal deputy director Dr. Anne Schuchat. "Taking a terrible human toll, two million Americans get infections from antibiotic resistance and 23,000 die from those infections each year."

In response to this growing threat to public health, the CDC has launched a containment strategy that includes a nationwide lab network for identifying new and "unusual" antibiotic-resistant germs.

Last year, as the CDC's new Vital Sign report outlines, the agency's nationwide network of labs tested 5,776 samples for "genes that were highly resistant or rare with special resistance that could spread."

"Of the 5,776, about one in four of the bacteria had a gene that helps it spread its resistance. And there were 221 instances of an especially rare resistance gene," Schuchat told reporters in a press briefing.

Patients who had contracted the "nightmare bateria" were at hospitals as well as healthcare facilities such as nursing homes. They were battling pneumonia, urinary tract infections, blood stream infections, and other types of infections. Although the report did not detail how many cases were fatal, Schuchat noted past research suggests "up to 50 percent can result in death."

While Schuchat admitted that the number of "nightmare bacteria" cases was higher than she expected, she added, "We hope though that this won't be an inevitable march upward, but that by finding them early when there's only one in the facility we can stop this from becoming very, very common."

The CDC containment strategy calls for a coordinated effort among healthcare facilities, labs, health departments, and CDC's lab network to rapidly identify resistance; implement infection control assessments; test patients who are not showing symptoms but may carry and spread the germ; and continue infection control assessments until the spread of that particular germ has stopped.

"Health departments using the approach have conducted infection control assessments and colonization screenings within 48 hours of finding unusual resistance and have reported no further transmission during follow-up over several weeks," the agency said in a statement. For the superbug CRE, "estimates show that the containment strategy would prevent as many as 1,600 new infections in three years in a single state--a 76 percent reduction."

Donald Trump’s attacks on democracy, justice, and a free press are escalating — putting everything we stand for at risk. We believe a better world is possible, but we can’t get there without your support. Common Dreams stands apart. We answer only to you — our readers, activists, and changemakers — not to billionaires or corporations. Our independence allows us to cover the vital stories that others won’t, spotlighting movements for peace, equality, and human rights. Right now, our work faces unprecedented challenges. Misinformation is spreading, journalists are under attack, and financial pressures are mounting. As a reader-supported, nonprofit newsroom, your support is crucial to keep this journalism alive. Whatever you can give — $10, $25, or $100 — helps us stay strong and responsive when the world needs us most. Together, we’ll continue to build the independent, courageous journalism our movement relies on. Thank you for being part of this community. |

Adding to mounting concerns about widespread antibiotic resistance, U.S. public health officials detected more than 220 cases of what they described as "nightmare bacteria" across more than half the country last year, according to a new government report.

In just nine months of surveillance during 2017, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) found "nightmare bacteria" with "unusual" resistance in 27 states, fueling the agency's warnings that "antibiotic-resistant germs can spread like wildfire."

The CDC considers antibiotic-resistant germs "unusual" if they are: resistant to all or most antibiotics; uncommon in a geographic area or the U.S.; or have genes that allow them to spread their resistance to other germs.

These "dangerous pathogens, hiding in plain sight...can cause infections that are difficult or impossible to treat," explained CDC principal deputy director Dr. Anne Schuchat. "Taking a terrible human toll, two million Americans get infections from antibiotic resistance and 23,000 die from those infections each year."

In response to this growing threat to public health, the CDC has launched a containment strategy that includes a nationwide lab network for identifying new and "unusual" antibiotic-resistant germs.

Last year, as the CDC's new Vital Sign report outlines, the agency's nationwide network of labs tested 5,776 samples for "genes that were highly resistant or rare with special resistance that could spread."

"Of the 5,776, about one in four of the bacteria had a gene that helps it spread its resistance. And there were 221 instances of an especially rare resistance gene," Schuchat told reporters in a press briefing.

Patients who had contracted the "nightmare bateria" were at hospitals as well as healthcare facilities such as nursing homes. They were battling pneumonia, urinary tract infections, blood stream infections, and other types of infections. Although the report did not detail how many cases were fatal, Schuchat noted past research suggests "up to 50 percent can result in death."

While Schuchat admitted that the number of "nightmare bacteria" cases was higher than she expected, she added, "We hope though that this won't be an inevitable march upward, but that by finding them early when there's only one in the facility we can stop this from becoming very, very common."

The CDC containment strategy calls for a coordinated effort among healthcare facilities, labs, health departments, and CDC's lab network to rapidly identify resistance; implement infection control assessments; test patients who are not showing symptoms but may carry and spread the germ; and continue infection control assessments until the spread of that particular germ has stopped.

"Health departments using the approach have conducted infection control assessments and colonization screenings within 48 hours of finding unusual resistance and have reported no further transmission during follow-up over several weeks," the agency said in a statement. For the superbug CRE, "estimates show that the containment strategy would prevent as many as 1,600 new infections in three years in a single state--a 76 percent reduction."

Adding to mounting concerns about widespread antibiotic resistance, U.S. public health officials detected more than 220 cases of what they described as "nightmare bacteria" across more than half the country last year, according to a new government report.

In just nine months of surveillance during 2017, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) found "nightmare bacteria" with "unusual" resistance in 27 states, fueling the agency's warnings that "antibiotic-resistant germs can spread like wildfire."

The CDC considers antibiotic-resistant germs "unusual" if they are: resistant to all or most antibiotics; uncommon in a geographic area or the U.S.; or have genes that allow them to spread their resistance to other germs.

These "dangerous pathogens, hiding in plain sight...can cause infections that are difficult or impossible to treat," explained CDC principal deputy director Dr. Anne Schuchat. "Taking a terrible human toll, two million Americans get infections from antibiotic resistance and 23,000 die from those infections each year."

In response to this growing threat to public health, the CDC has launched a containment strategy that includes a nationwide lab network for identifying new and "unusual" antibiotic-resistant germs.

Last year, as the CDC's new Vital Sign report outlines, the agency's nationwide network of labs tested 5,776 samples for "genes that were highly resistant or rare with special resistance that could spread."

"Of the 5,776, about one in four of the bacteria had a gene that helps it spread its resistance. And there were 221 instances of an especially rare resistance gene," Schuchat told reporters in a press briefing.

Patients who had contracted the "nightmare bateria" were at hospitals as well as healthcare facilities such as nursing homes. They were battling pneumonia, urinary tract infections, blood stream infections, and other types of infections. Although the report did not detail how many cases were fatal, Schuchat noted past research suggests "up to 50 percent can result in death."

While Schuchat admitted that the number of "nightmare bacteria" cases was higher than she expected, she added, "We hope though that this won't be an inevitable march upward, but that by finding them early when there's only one in the facility we can stop this from becoming very, very common."

The CDC containment strategy calls for a coordinated effort among healthcare facilities, labs, health departments, and CDC's lab network to rapidly identify resistance; implement infection control assessments; test patients who are not showing symptoms but may carry and spread the germ; and continue infection control assessments until the spread of that particular germ has stopped.

"Health departments using the approach have conducted infection control assessments and colonization screenings within 48 hours of finding unusual resistance and have reported no further transmission during follow-up over several weeks," the agency said in a statement. For the superbug CRE, "estimates show that the containment strategy would prevent as many as 1,600 new infections in three years in a single state--a 76 percent reduction."