SUBSCRIBE TO OUR FREE NEWSLETTER

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

5

#000000

#FFFFFF

To donate by check, phone, or other method, see our More Ways to Give page.

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

And when that happens, as tobacco companies found out over the last decade or more, people who don't smoke, don't buy tobacco.

Additionally, as governments experienced the health cost savings that could be garnered as tobacco consumption rates fell, they began thinking of ways to assist the no-smoking trends.

As developed nations created more highly regulated systems for the control, advertisement, and sale of tobacco, the industry found itself focused on expanding its business in less-developed nations where education on the dangers of tobacco were less advanced and government restrictions were short of those found in the U.S., Canada, Europe, and other rich countries.

But, according to an in-depth analysis by the New York Times on Friday, as developing nations now try to increase their control over the deadly industry, the large tobacco corporations--citing international trade agreements and various treaties--are using their financial and legal muscle to intimidate governments from adopting those stricter regulatory steps.

The debate is being touched off by a major Pacific trade deal, known as the Trans-Pacific Partnership (or TPP), in which the rights of corporations are being seen to supercede those of local government, with built-in structures that allow private companies--in this case some of the world's largest producers of cigarettes and other tobacco products--to file suit against governments who try to toughen restrictions.

As the Times reports:

...public health advocates say the current wording [in the TPP] would not stop countries from being sued when they adopt strong tobacco control measures, though some trade experts said it might make the companies less likely to win. [...]

Tobacco consumption more than doubled in the developing world from 1970 to 2000, according to the United Nations. Much of the increase was in China, but there has also been substantial growth in Africa, where smoking rates have traditionally been low. More than three-quarters of the world's smokers now live in the developing world.

Dr. Margaret Chan, director general of the W.H.O., said in a speech last year that legal actions against Uruguay, Norway and Australia were "deliberately designed to instill fear" in countries trying to reduce smoking.

"The wolf is no longer in sheep's clothing, and its teeth are bared," she said.

According to the Center for Policy Analysis on Trade and Health (CPATH), the US government--though it helped expose the health dangers of tobacco use in the 1990's--is now setting the stage for tobacco companies to exploit trade policy agreements like the TPP as a way to exploit consumer markets overseas in a way that could deeply harm public health in foreign countries.

"U.S. proposals for the Trans Pacific Partnership (TPP) would threaten global efforts at tobacco control by enhancing the tobacco industry's ability to undermine tobacco regulation through litigation," the group said in a statement following the latest round of talks that ended in Singapore earlier this week.

CPATH and other health advocates are calling for a "carve out" for tobacco regulations, meaning that corporations could not use the authority of the trade agreement to file suit against governments who strengthen their domestic laws to protect public health.

"The only genuine solution would be to carve out (meaning to remove) tobacco control laws and regulations from trade agreements," the CPATH statement continued.

But though Malaysia, one of the 12 nations party to the TPP talks, has advanced a proposal that would complement the language enshrined in the World Health Organization's Framework Convention on Tobacco Control--to which all TPP countries are signatories--the U.S. Trade Representative, according to the CPATH, "has not agreed, nor exercised leadership towards a viable resolution."

What critics say it comes down to, at least for the tobacco companies, is being able to push their extremely health-adverse product on unwitting consumers by strong-arming the governments who try to legislate stronger consumer protections or industry standards.

As the Times adds, trade agreements are sold to the public as ways to spur international and domestic economic activity, but they also

allow companies to sue directly, instead of having to persuade a state to take up their case. [Such lawsuits] have proliferated since the 1990s, and number around 3,000, up from a few hundred in the late 1980s, according to Robert Stumberg, a law professor at the Harrison Institute for Public Law at Georgetown University, whose clients include antismoking groups.

In Africa, at least four countries -- Namibia, Gabon, Togo and Uganda -- have received warnings from the tobacco industry that their laws run afoul of international treaties, said Patricia Lambert, director of the international legal consortium at the Campaign for Tobacco Free Kids.

"They're trying to intimidate everybody," said Jonathan Liberman, director of the McCabe Center for Law and Cancer in Australia, which gives legal support to countries that have been challenged by tobacco companies. In Namibia, the tobacco industry has said that requiring large warning labels on cigarette packages violates its intellectual property rights and could fuel counterfeiting.

Slammed broadly for its deference to corporate interests while undermining labor, environmental, and consumer protections, the TPP talks are broadly under fire for the secrecy under which they have taken place. In the U.S., the Obama administration has been roundly criticized for trying to get "fast track" authority for the deal, which means that Congress will only have an opportunity to vote up or down on a final draft of the agreement without offering changes or amendments.

CPATH's co-director Joseph E. Brenner is among those slamming both the content of the deal and the process of the negotiations. "We must restore democratic practice and principles of economic and social sustainability to the trade negotiations process," Brenner said. "We need a 21st century trade agreement. Carving out tobacco could signal the dawn of that century."

___________________________________________

Dear Common Dreams reader, The U.S. is on a fast track to authoritarianism like nothing I've ever seen. Meanwhile, corporate news outlets are utterly capitulating to Trump, twisting their coverage to avoid drawing his ire while lining up to stuff cash in his pockets. That's why I believe that Common Dreams is doing the best and most consequential reporting that we've ever done. Our small but mighty team is a progressive reporting powerhouse, covering the news every day that the corporate media never will. Our mission has always been simple: To inform. To inspire. And to ignite change for the common good. Now here's the key piece that I want all our readers to understand: None of this would be possible without your financial support. That's not just some fundraising cliche. It's the absolute and literal truth. We don't accept corporate advertising and never will. We don't have a paywall because we don't think people should be blocked from critical news based on their ability to pay. Everything we do is funded by the donations of readers like you. Will you donate now to help power the nonprofit, independent reporting of Common Dreams? Thank you for being a vital member of our community. Together, we can keep independent journalism alive when it’s needed most. - Craig Brown, Co-founder |

And when that happens, as tobacco companies found out over the last decade or more, people who don't smoke, don't buy tobacco.

Additionally, as governments experienced the health cost savings that could be garnered as tobacco consumption rates fell, they began thinking of ways to assist the no-smoking trends.

As developed nations created more highly regulated systems for the control, advertisement, and sale of tobacco, the industry found itself focused on expanding its business in less-developed nations where education on the dangers of tobacco were less advanced and government restrictions were short of those found in the U.S., Canada, Europe, and other rich countries.

But, according to an in-depth analysis by the New York Times on Friday, as developing nations now try to increase their control over the deadly industry, the large tobacco corporations--citing international trade agreements and various treaties--are using their financial and legal muscle to intimidate governments from adopting those stricter regulatory steps.

The debate is being touched off by a major Pacific trade deal, known as the Trans-Pacific Partnership (or TPP), in which the rights of corporations are being seen to supercede those of local government, with built-in structures that allow private companies--in this case some of the world's largest producers of cigarettes and other tobacco products--to file suit against governments who try to toughen restrictions.

As the Times reports:

...public health advocates say the current wording [in the TPP] would not stop countries from being sued when they adopt strong tobacco control measures, though some trade experts said it might make the companies less likely to win. [...]

Tobacco consumption more than doubled in the developing world from 1970 to 2000, according to the United Nations. Much of the increase was in China, but there has also been substantial growth in Africa, where smoking rates have traditionally been low. More than three-quarters of the world's smokers now live in the developing world.

Dr. Margaret Chan, director general of the W.H.O., said in a speech last year that legal actions against Uruguay, Norway and Australia were "deliberately designed to instill fear" in countries trying to reduce smoking.

"The wolf is no longer in sheep's clothing, and its teeth are bared," she said.

According to the Center for Policy Analysis on Trade and Health (CPATH), the US government--though it helped expose the health dangers of tobacco use in the 1990's--is now setting the stage for tobacco companies to exploit trade policy agreements like the TPP as a way to exploit consumer markets overseas in a way that could deeply harm public health in foreign countries.

"U.S. proposals for the Trans Pacific Partnership (TPP) would threaten global efforts at tobacco control by enhancing the tobacco industry's ability to undermine tobacco regulation through litigation," the group said in a statement following the latest round of talks that ended in Singapore earlier this week.

CPATH and other health advocates are calling for a "carve out" for tobacco regulations, meaning that corporations could not use the authority of the trade agreement to file suit against governments who strengthen their domestic laws to protect public health.

"The only genuine solution would be to carve out (meaning to remove) tobacco control laws and regulations from trade agreements," the CPATH statement continued.

But though Malaysia, one of the 12 nations party to the TPP talks, has advanced a proposal that would complement the language enshrined in the World Health Organization's Framework Convention on Tobacco Control--to which all TPP countries are signatories--the U.S. Trade Representative, according to the CPATH, "has not agreed, nor exercised leadership towards a viable resolution."

What critics say it comes down to, at least for the tobacco companies, is being able to push their extremely health-adverse product on unwitting consumers by strong-arming the governments who try to legislate stronger consumer protections or industry standards.

As the Times adds, trade agreements are sold to the public as ways to spur international and domestic economic activity, but they also

allow companies to sue directly, instead of having to persuade a state to take up their case. [Such lawsuits] have proliferated since the 1990s, and number around 3,000, up from a few hundred in the late 1980s, according to Robert Stumberg, a law professor at the Harrison Institute for Public Law at Georgetown University, whose clients include antismoking groups.

In Africa, at least four countries -- Namibia, Gabon, Togo and Uganda -- have received warnings from the tobacco industry that their laws run afoul of international treaties, said Patricia Lambert, director of the international legal consortium at the Campaign for Tobacco Free Kids.

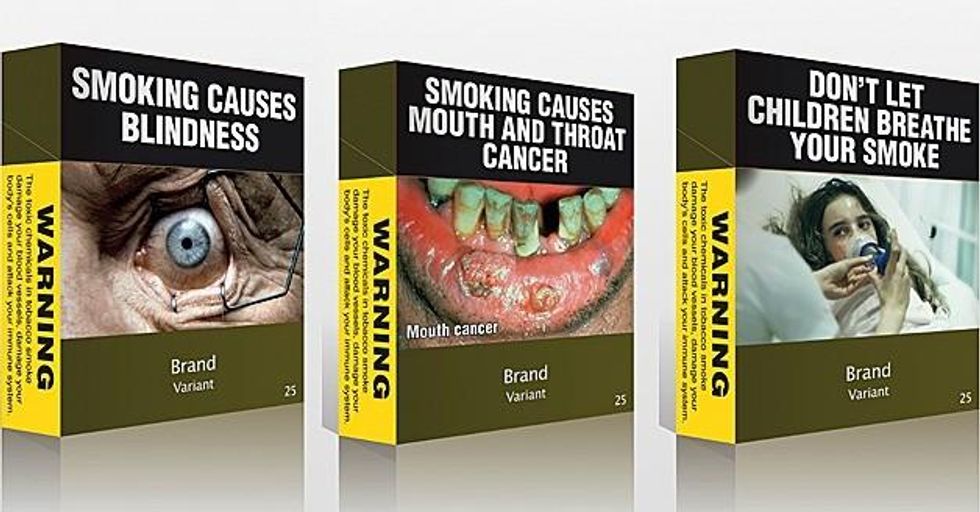

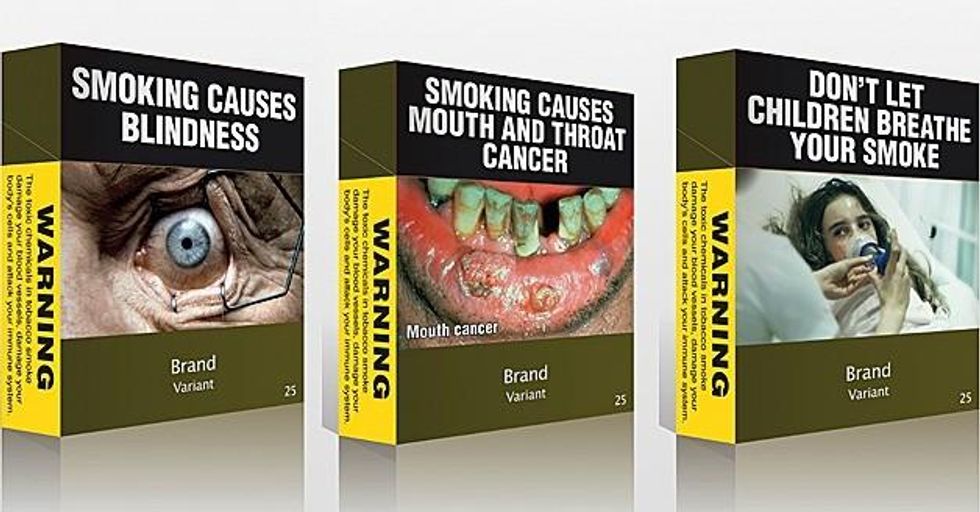

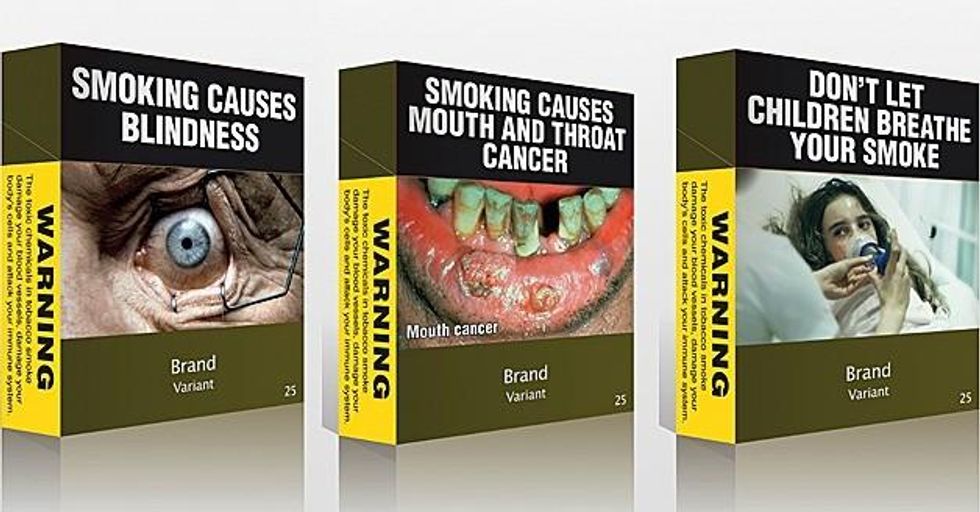

"They're trying to intimidate everybody," said Jonathan Liberman, director of the McCabe Center for Law and Cancer in Australia, which gives legal support to countries that have been challenged by tobacco companies. In Namibia, the tobacco industry has said that requiring large warning labels on cigarette packages violates its intellectual property rights and could fuel counterfeiting.

Slammed broadly for its deference to corporate interests while undermining labor, environmental, and consumer protections, the TPP talks are broadly under fire for the secrecy under which they have taken place. In the U.S., the Obama administration has been roundly criticized for trying to get "fast track" authority for the deal, which means that Congress will only have an opportunity to vote up or down on a final draft of the agreement without offering changes or amendments.

CPATH's co-director Joseph E. Brenner is among those slamming both the content of the deal and the process of the negotiations. "We must restore democratic practice and principles of economic and social sustainability to the trade negotiations process," Brenner said. "We need a 21st century trade agreement. Carving out tobacco could signal the dawn of that century."

___________________________________________

And when that happens, as tobacco companies found out over the last decade or more, people who don't smoke, don't buy tobacco.

Additionally, as governments experienced the health cost savings that could be garnered as tobacco consumption rates fell, they began thinking of ways to assist the no-smoking trends.

As developed nations created more highly regulated systems for the control, advertisement, and sale of tobacco, the industry found itself focused on expanding its business in less-developed nations where education on the dangers of tobacco were less advanced and government restrictions were short of those found in the U.S., Canada, Europe, and other rich countries.

But, according to an in-depth analysis by the New York Times on Friday, as developing nations now try to increase their control over the deadly industry, the large tobacco corporations--citing international trade agreements and various treaties--are using their financial and legal muscle to intimidate governments from adopting those stricter regulatory steps.

The debate is being touched off by a major Pacific trade deal, known as the Trans-Pacific Partnership (or TPP), in which the rights of corporations are being seen to supercede those of local government, with built-in structures that allow private companies--in this case some of the world's largest producers of cigarettes and other tobacco products--to file suit against governments who try to toughen restrictions.

As the Times reports:

...public health advocates say the current wording [in the TPP] would not stop countries from being sued when they adopt strong tobacco control measures, though some trade experts said it might make the companies less likely to win. [...]

Tobacco consumption more than doubled in the developing world from 1970 to 2000, according to the United Nations. Much of the increase was in China, but there has also been substantial growth in Africa, where smoking rates have traditionally been low. More than three-quarters of the world's smokers now live in the developing world.

Dr. Margaret Chan, director general of the W.H.O., said in a speech last year that legal actions against Uruguay, Norway and Australia were "deliberately designed to instill fear" in countries trying to reduce smoking.

"The wolf is no longer in sheep's clothing, and its teeth are bared," she said.

According to the Center for Policy Analysis on Trade and Health (CPATH), the US government--though it helped expose the health dangers of tobacco use in the 1990's--is now setting the stage for tobacco companies to exploit trade policy agreements like the TPP as a way to exploit consumer markets overseas in a way that could deeply harm public health in foreign countries.

"U.S. proposals for the Trans Pacific Partnership (TPP) would threaten global efforts at tobacco control by enhancing the tobacco industry's ability to undermine tobacco regulation through litigation," the group said in a statement following the latest round of talks that ended in Singapore earlier this week.

CPATH and other health advocates are calling for a "carve out" for tobacco regulations, meaning that corporations could not use the authority of the trade agreement to file suit against governments who strengthen their domestic laws to protect public health.

"The only genuine solution would be to carve out (meaning to remove) tobacco control laws and regulations from trade agreements," the CPATH statement continued.

But though Malaysia, one of the 12 nations party to the TPP talks, has advanced a proposal that would complement the language enshrined in the World Health Organization's Framework Convention on Tobacco Control--to which all TPP countries are signatories--the U.S. Trade Representative, according to the CPATH, "has not agreed, nor exercised leadership towards a viable resolution."

What critics say it comes down to, at least for the tobacco companies, is being able to push their extremely health-adverse product on unwitting consumers by strong-arming the governments who try to legislate stronger consumer protections or industry standards.

As the Times adds, trade agreements are sold to the public as ways to spur international and domestic economic activity, but they also

allow companies to sue directly, instead of having to persuade a state to take up their case. [Such lawsuits] have proliferated since the 1990s, and number around 3,000, up from a few hundred in the late 1980s, according to Robert Stumberg, a law professor at the Harrison Institute for Public Law at Georgetown University, whose clients include antismoking groups.

In Africa, at least four countries -- Namibia, Gabon, Togo and Uganda -- have received warnings from the tobacco industry that their laws run afoul of international treaties, said Patricia Lambert, director of the international legal consortium at the Campaign for Tobacco Free Kids.

"They're trying to intimidate everybody," said Jonathan Liberman, director of the McCabe Center for Law and Cancer in Australia, which gives legal support to countries that have been challenged by tobacco companies. In Namibia, the tobacco industry has said that requiring large warning labels on cigarette packages violates its intellectual property rights and could fuel counterfeiting.

Slammed broadly for its deference to corporate interests while undermining labor, environmental, and consumer protections, the TPP talks are broadly under fire for the secrecy under which they have taken place. In the U.S., the Obama administration has been roundly criticized for trying to get "fast track" authority for the deal, which means that Congress will only have an opportunity to vote up or down on a final draft of the agreement without offering changes or amendments.

CPATH's co-director Joseph E. Brenner is among those slamming both the content of the deal and the process of the negotiations. "We must restore democratic practice and principles of economic and social sustainability to the trade negotiations process," Brenner said. "We need a 21st century trade agreement. Carving out tobacco could signal the dawn of that century."

___________________________________________