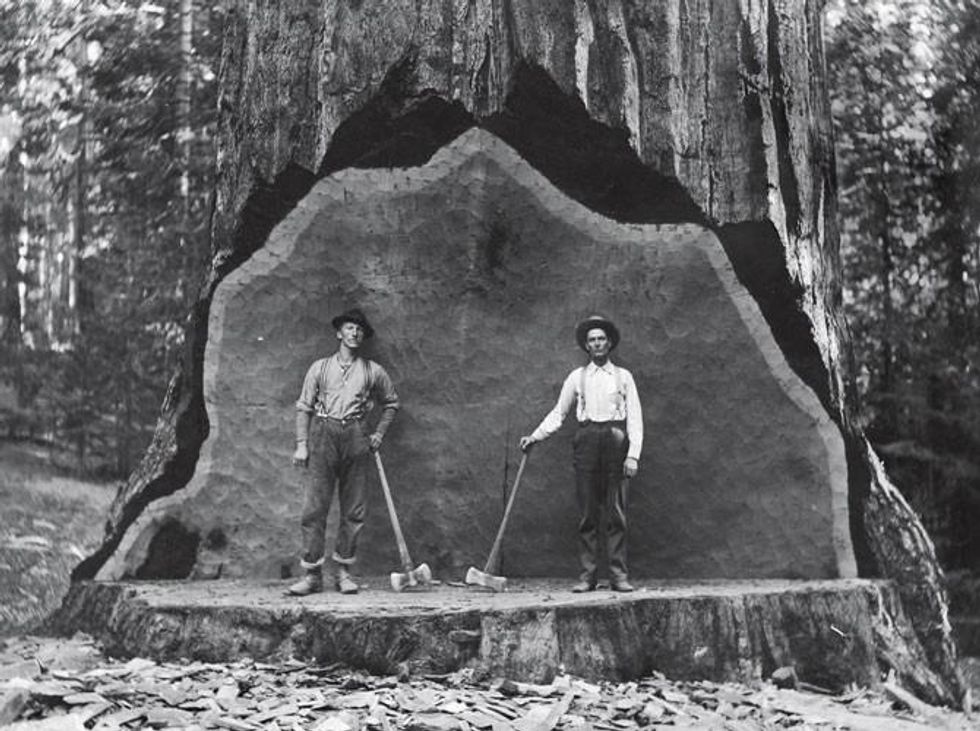

Study: World's Mighty Giants Dying off at Alarming Rate

'We are talking about the loss of the biggest living organisms on the planet'

The world's biggest and oldest living trees are disappearing and will never be replaced, according to a new review of global ecosystems.

The study, published last week in the journal Science, found that trees between 100 and 300 years old are dying off at an alarming rate.

"What we're seeing is a global phenomenon," said the paper's lead author, ecologist David Lindenmayer of Australian National University. "There are different sets of drivers--it might be fire, logging, drought, disease--but they all lead to basically the same outcome."

Though causes for the decline are myriad, the common factor is human intervention. Some of the findings, The Seattle Times reports:

In Scandinavia, logging companies are simply targeting the biggest, oldest trees.

On the savannas of Northern Australia, nonnative grasses planted to improve cattle and sheep grazing burn seven times hotter than native grass, decimating trees that weathered centuries of normal fire.

In Brazil, where rain forests have been reduced to fragments, old trees are much more vulnerable to being toppled by wind and parasitized by strangler vines that proliferate after logging.

Many forest ecosystems are so altered by invasive species, human management and shifting climate that young trees no longer are able to grow into behemoths.

The increase in threats is causing large trees to die off at ten times their normal rate. This raises concern because these giants are essential bedrocks to forest ecosystems.

"Big, old trees are not just enlarged young trees," Jerry F. Franklin of the University of Washington, another of the study's authors, told the New York Times. "Old trees have idiosyncratic features--a different canopy, different branch systems, a lot of cavities, thicker bark and more heartwood. They provide a lot more habitat and niches."

In some forests, nearly a third of all birds, reptiles, mammals or marsupials make their homes in ancient trees, the scientists reported. Large trees also capture and store significant amounts of carbon and recycle surrounding soil nutrients, which in turn encourages new growth.

The Science paper is one of the first to use evidence collected from across the globe to make the argument that big trees deserve special consideration

"We're dramatically reducing the number of big trees," Franklin said. "As part of our active management, we need to be planning to restore historic levels of those big, old trees."

"It is a very, very disturbing trend," added second co-author Bill Laurance, from James Cook University in Australia. "We are talking about the loss of the biggest living organisms on the planet."

An Urgent Message From Our Co-Founder

Dear Common Dreams reader, The U.S. is on a fast track to authoritarianism like nothing I've ever seen. Meanwhile, corporate news outlets are utterly capitulating to Trump, twisting their coverage to avoid drawing his ire while lining up to stuff cash in his pockets. That's why I believe that Common Dreams is doing the best and most consequential reporting that we've ever done. Our small but mighty team is a progressive reporting powerhouse, covering the news every day that the corporate media never will. Our mission has always been simple: To inform. To inspire. And to ignite change for the common good. Now here's the key piece that I want all our readers to understand: None of this would be possible without your financial support. That's not just some fundraising cliche. It's the absolute and literal truth. We don't accept corporate advertising and never will. We don't have a paywall because we don't think people should be blocked from critical news based on their ability to pay. Everything we do is funded by the donations of readers like you. Will you donate now to help power the nonprofit, independent reporting of Common Dreams? Thank you for being a vital member of our community. Together, we can keep independent journalism alive when it’s needed most. - Craig Brown, Co-founder |

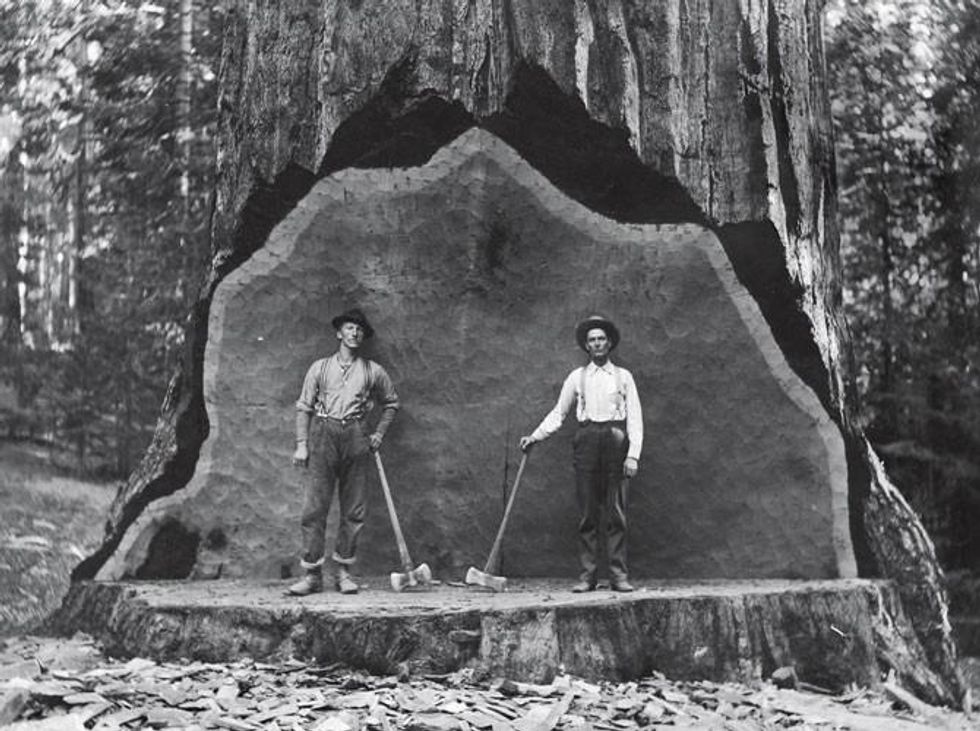

The world's biggest and oldest living trees are disappearing and will never be replaced, according to a new review of global ecosystems.

The study, published last week in the journal Science, found that trees between 100 and 300 years old are dying off at an alarming rate.

"What we're seeing is a global phenomenon," said the paper's lead author, ecologist David Lindenmayer of Australian National University. "There are different sets of drivers--it might be fire, logging, drought, disease--but they all lead to basically the same outcome."

Though causes for the decline are myriad, the common factor is human intervention. Some of the findings, The Seattle Times reports:

In Scandinavia, logging companies are simply targeting the biggest, oldest trees.

On the savannas of Northern Australia, nonnative grasses planted to improve cattle and sheep grazing burn seven times hotter than native grass, decimating trees that weathered centuries of normal fire.

In Brazil, where rain forests have been reduced to fragments, old trees are much more vulnerable to being toppled by wind and parasitized by strangler vines that proliferate after logging.

Many forest ecosystems are so altered by invasive species, human management and shifting climate that young trees no longer are able to grow into behemoths.

The increase in threats is causing large trees to die off at ten times their normal rate. This raises concern because these giants are essential bedrocks to forest ecosystems.

"Big, old trees are not just enlarged young trees," Jerry F. Franklin of the University of Washington, another of the study's authors, told the New York Times. "Old trees have idiosyncratic features--a different canopy, different branch systems, a lot of cavities, thicker bark and more heartwood. They provide a lot more habitat and niches."

In some forests, nearly a third of all birds, reptiles, mammals or marsupials make their homes in ancient trees, the scientists reported. Large trees also capture and store significant amounts of carbon and recycle surrounding soil nutrients, which in turn encourages new growth.

The Science paper is one of the first to use evidence collected from across the globe to make the argument that big trees deserve special consideration

"We're dramatically reducing the number of big trees," Franklin said. "As part of our active management, we need to be planning to restore historic levels of those big, old trees."

"It is a very, very disturbing trend," added second co-author Bill Laurance, from James Cook University in Australia. "We are talking about the loss of the biggest living organisms on the planet."

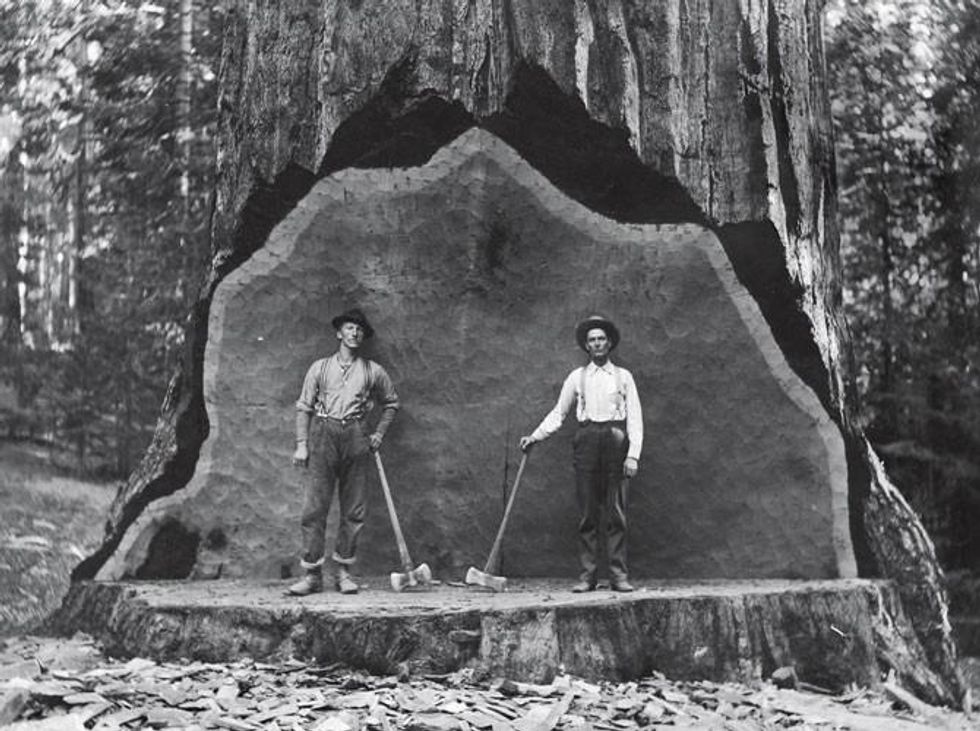

The world's biggest and oldest living trees are disappearing and will never be replaced, according to a new review of global ecosystems.

The study, published last week in the journal Science, found that trees between 100 and 300 years old are dying off at an alarming rate.

"What we're seeing is a global phenomenon," said the paper's lead author, ecologist David Lindenmayer of Australian National University. "There are different sets of drivers--it might be fire, logging, drought, disease--but they all lead to basically the same outcome."

Though causes for the decline are myriad, the common factor is human intervention. Some of the findings, The Seattle Times reports:

In Scandinavia, logging companies are simply targeting the biggest, oldest trees.

On the savannas of Northern Australia, nonnative grasses planted to improve cattle and sheep grazing burn seven times hotter than native grass, decimating trees that weathered centuries of normal fire.

In Brazil, where rain forests have been reduced to fragments, old trees are much more vulnerable to being toppled by wind and parasitized by strangler vines that proliferate after logging.

Many forest ecosystems are so altered by invasive species, human management and shifting climate that young trees no longer are able to grow into behemoths.

The increase in threats is causing large trees to die off at ten times their normal rate. This raises concern because these giants are essential bedrocks to forest ecosystems.

"Big, old trees are not just enlarged young trees," Jerry F. Franklin of the University of Washington, another of the study's authors, told the New York Times. "Old trees have idiosyncratic features--a different canopy, different branch systems, a lot of cavities, thicker bark and more heartwood. They provide a lot more habitat and niches."

In some forests, nearly a third of all birds, reptiles, mammals or marsupials make their homes in ancient trees, the scientists reported. Large trees also capture and store significant amounts of carbon and recycle surrounding soil nutrients, which in turn encourages new growth.

The Science paper is one of the first to use evidence collected from across the globe to make the argument that big trees deserve special consideration

"We're dramatically reducing the number of big trees," Franklin said. "As part of our active management, we need to be planning to restore historic levels of those big, old trees."

"It is a very, very disturbing trend," added second co-author Bill Laurance, from James Cook University in Australia. "We are talking about the loss of the biggest living organisms on the planet."