SUBSCRIBE TO OUR FREE NEWSLETTER

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

5

#000000

#FFFFFF

To donate by check, phone, or other method, see our More Ways to Give page.

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

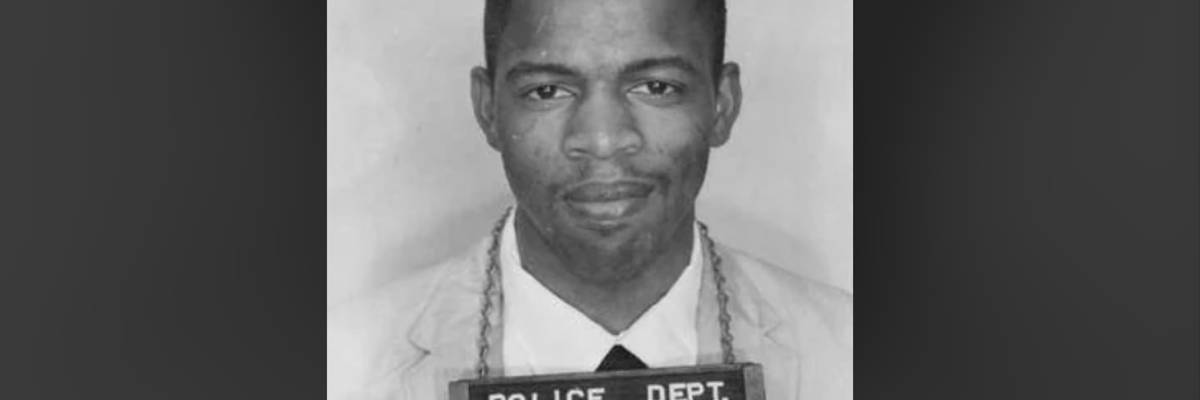

John Lewis' smiling 1961 mugshot after being arrested for using a "white" bathroom in Mississippi.

Taking a break from the awful to celebrate - remember that? - indefatigable civil rights icon, all-round mensch and former chicken preacher John Lewis, who died five years ago today after a lifetime of good trouble. The peerless "moral compass of Congress," now sorely lacking, Lewis never gave up seeking his "beloved community" even as he acknowledged he might never live in it. "Our struggle is not (of) a day, month or year," he said: "It is the struggle of a lifetime."

Over 60 years, Lewis' lifetime of struggle extended from student lunch-counter sit-ins, beatings as one of 13 original volunteers on Freedom Rides, founding and leading SNCC, speaking fire as the youngest organizer of the March in Washington and Bloody Sunday's seminal Selma march to, eventually, the halls of Congress, where he served 17 terms while persisting in making good trouble in ongoing fights for peace, immigrants, LGBTQ rights and voting rights that, he resolutely declared, “For generations we have marched, fought and even died for." Above all, "John believed in the power of ordinary people to do extraordinary things."

Born the trouble-making son of sharecroppers outside Troy, Alabama in 1940, he attended segregated public schools. As a boy, he wanted to be a minister, and famously practiced his oratory on the family chickens. Denied a library card for the color of his skin, he became a voracious reader. He was a teenager when he heard, riveted, Martin Luther King Jr. preaching on the radio. They met when Lewis was trying to become the first Black student at Alabama’s segregated Troy State University; he ultimately attended the American Baptist Theological Seminary and Nashville's Fisk University.

Along with Diane Nash and other members of the Nashville Student Movement, he began organizing sit-ins at whites-only lunch counters after four Black college students in Greensboro, N.C. first did it; there, staff refused to serve them but the students wouldn't leave, and then went back with more recruits. Lewis' first arrest came in February 1960 at age 20, when he sat down at a segregated Woolworth's lunch counter in Nashville. Angry white patrons beat and tried to remove him and his fellow protesters; when police finally arrived, they arrested the protesters.

“I didn't necessarily want to go to jail," he recalled in a 1973 interview. “But we knew (it) would rally the student community." And it did: By the end of the day 98 students were in jail, hundreds followed, and that spring Nashville lunch counters began serving Blacks. "Nashville prepared me," he said. "We grew up sitting down or sitting in. And we grew up very fast." Soon, Lewis was also traveling through a belligerent, still-segregated South as a Freedom Rider, enduring more beatings and arrests. Between 1960 and 1966, he was arrested at least 40 times; as a Congressman, he was arrested five more times.

As the 23-year-old head of SNCC, he gave a fiery speech at 1963's MLK Jr.-led March on Washington. Older fellow-organizers - Philip Randolph, 74, and James Farmer, Whitney Young, Roy Wilkins - urged him to tone it down; he scaled back critiques of JFK and dropped a "scorched earth" reference, but it was still potent. "To those who have said, 'Be patient'...We are tired. We are tired of being beaten by policemen, (of) seeing our people locked up in jail... How long can we be patient? We want our freedom and we want it now...We shall splinter the segregated South into a thousand pieces and put them together in an image of God and democracy.”

Two years later, hands tucked in his genteel tan overcoat, he led over 600 voting rights protesters over Selma's Edmund Pettus Bridge, named for a Ku Klux Klan leader, in what became known as Bloody Sunday. State troopers and "deputized" white thugs beat him so badly - still-chilling video here - they fractured his skull. Images of the brutality shocked a complacent nation, and eventually helped led to the Voting Rights Act of 1965. When he joined Pres. Obama at the site 55 years later, Lewis was still urging anyone who'd listen to "get in good trouble, necessary trouble, and help redeem the soul of America."

In 1981, Lewis was elected to the Atlanta City Council; in 1986, he won what became his longtime seat in Congress. He spent much of his career in the minority, but when Dems won the House in 2006, he became his party’s senior deputy whip. Humble, friendly, eloquent, he was revered as the "moral compass" of the House. His last arrest was in 2013 as one of 8 Dem lawmakers, including Keith Ellison and Al Green, arrested at a sit-in for immigration reform; police arrested 200 people for "disrupting" the street. Lewis posted a photo: "Arrest number 45." Always, he calmly insisted, "We will find a way to make a way out of no way.”

The last survivor of the civil rights icons, he worked for 15 years toward the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History. When Trump ran in 2016, he sensed the urgency, posting, "I’ve marched, protested, been beaten and arrested - all for the right to vote. Friends (gave) their lives. Honor their sacrifice. Vote." He refused to attend the inauguration because Trump wasn't a "legitimate president." He called him "a racist" after the "shithole countries" slur, and voted for impeachment: “When you see something that is not right, not just, not fair, you have a moral obligation to say something, to do something. Our children and their children will ask us, 'What did you do? What did you say?'"

He died of pancreatic cancer on July 17, 2020, at 80. Nancy Pelosi called him "one of the greatest heroes of American history...May his memory be an inspiration that moves us all to, in the face of injustice, make ‘good trouble, necessary trouble.'” This week, Congressional Black Caucus members honored his legacy by vowing to do the same and reading his works. "His words are more necessary today than ever," said Rep. Jennifer McClellan. "John Lewis understood just as Dr. King did he wasn’t going to reach the promised land of that more perfect union. But he fought for it."

Since his death, Dems have continued to reintroduce the John Lewis Voting Rights Advancement Act to restore key, GOP-trashed provisions of the 1965 Voting Rights Act. It has repeatedly stalled in Congress, and for now will likely continue to. But Lewis' colleagues vow to keep pushing for it, said Georgia Rep. Lucy McBath, "to honor his legacy with unshakeable determination to fight for what is right and what is just." "Freedom is not a state; it is an act," said Lewis. "It is not some enchanted garden perched high (where) we can finally sit down and rest. Freedom is the continuous action we all must take." While, he attested at a Stacey Abrams event the year before he died, finding joy. May he rest in peace and power.

To those who feel nothing seems to change: "You must be able and prepared to give until you cannot give any more. We must use our time and our space on this little planet that we call Earth to make a lasting contribution, to leave it a little better than we found it, and now that need is greater than ever before.” - John Lewis, near the end of his life.

- YouTube www.youtube.com

Dear Common Dreams reader, The U.S. is on a fast track to authoritarianism like nothing I've ever seen. Meanwhile, corporate news outlets are utterly capitulating to Trump, twisting their coverage to avoid drawing his ire while lining up to stuff cash in his pockets. That's why I believe that Common Dreams is doing the best and most consequential reporting that we've ever done. Our small but mighty team is a progressive reporting powerhouse, covering the news every day that the corporate media never will. Our mission has always been simple: To inform. To inspire. And to ignite change for the common good. Now here's the key piece that I want all our readers to understand: None of this would be possible without your financial support. That's not just some fundraising cliche. It's the absolute and literal truth. We don't accept corporate advertising and never will. We don't have a paywall because we don't think people should be blocked from critical news based on their ability to pay. Everything we do is funded by the donations of readers like you. Will you donate now to help power the nonprofit, independent reporting of Common Dreams? Thank you for being a vital member of our community. Together, we can keep independent journalism alive when it’s needed most. - Craig Brown, Co-founder |

Taking a break from the awful to celebrate - remember that? - indefatigable civil rights icon, all-round mensch and former chicken preacher John Lewis, who died five years ago today after a lifetime of good trouble. The peerless "moral compass of Congress," now sorely lacking, Lewis never gave up seeking his "beloved community" even as he acknowledged he might never live in it. "Our struggle is not (of) a day, month or year," he said: "It is the struggle of a lifetime."

Over 60 years, Lewis' lifetime of struggle extended from student lunch-counter sit-ins, beatings as one of 13 original volunteers on Freedom Rides, founding and leading SNCC, speaking fire as the youngest organizer of the March in Washington and Bloody Sunday's seminal Selma march to, eventually, the halls of Congress, where he served 17 terms while persisting in making good trouble in ongoing fights for peace, immigrants, LGBTQ rights and voting rights that, he resolutely declared, “For generations we have marched, fought and even died for." Above all, "John believed in the power of ordinary people to do extraordinary things."

Born the trouble-making son of sharecroppers outside Troy, Alabama in 1940, he attended segregated public schools. As a boy, he wanted to be a minister, and famously practiced his oratory on the family chickens. Denied a library card for the color of his skin, he became a voracious reader. He was a teenager when he heard, riveted, Martin Luther King Jr. preaching on the radio. They met when Lewis was trying to become the first Black student at Alabama’s segregated Troy State University; he ultimately attended the American Baptist Theological Seminary and Nashville's Fisk University.

Along with Diane Nash and other members of the Nashville Student Movement, he began organizing sit-ins at whites-only lunch counters after four Black college students in Greensboro, N.C. first did it; there, staff refused to serve them but the students wouldn't leave, and then went back with more recruits. Lewis' first arrest came in February 1960 at age 20, when he sat down at a segregated Woolworth's lunch counter in Nashville. Angry white patrons beat and tried to remove him and his fellow protesters; when police finally arrived, they arrested the protesters.

“I didn't necessarily want to go to jail," he recalled in a 1973 interview. “But we knew (it) would rally the student community." And it did: By the end of the day 98 students were in jail, hundreds followed, and that spring Nashville lunch counters began serving Blacks. "Nashville prepared me," he said. "We grew up sitting down or sitting in. And we grew up very fast." Soon, Lewis was also traveling through a belligerent, still-segregated South as a Freedom Rider, enduring more beatings and arrests. Between 1960 and 1966, he was arrested at least 40 times; as a Congressman, he was arrested five more times.

As the 23-year-old head of SNCC, he gave a fiery speech at 1963's MLK Jr.-led March on Washington. Older fellow-organizers - Philip Randolph, 74, and James Farmer, Whitney Young, Roy Wilkins - urged him to tone it down; he scaled back critiques of JFK and dropped a "scorched earth" reference, but it was still potent. "To those who have said, 'Be patient'...We are tired. We are tired of being beaten by policemen, (of) seeing our people locked up in jail... How long can we be patient? We want our freedom and we want it now...We shall splinter the segregated South into a thousand pieces and put them together in an image of God and democracy.”

Two years later, hands tucked in his genteel tan overcoat, he led over 600 voting rights protesters over Selma's Edmund Pettus Bridge, named for a Ku Klux Klan leader, in what became known as Bloody Sunday. State troopers and "deputized" white thugs beat him so badly - still-chilling video here - they fractured his skull. Images of the brutality shocked a complacent nation, and eventually helped led to the Voting Rights Act of 1965. When he joined Pres. Obama at the site 55 years later, Lewis was still urging anyone who'd listen to "get in good trouble, necessary trouble, and help redeem the soul of America."

In 1981, Lewis was elected to the Atlanta City Council; in 1986, he won what became his longtime seat in Congress. He spent much of his career in the minority, but when Dems won the House in 2006, he became his party’s senior deputy whip. Humble, friendly, eloquent, he was revered as the "moral compass" of the House. His last arrest was in 2013 as one of 8 Dem lawmakers, including Keith Ellison and Al Green, arrested at a sit-in for immigration reform; police arrested 200 people for "disrupting" the street. Lewis posted a photo: "Arrest number 45." Always, he calmly insisted, "We will find a way to make a way out of no way.”

The last survivor of the civil rights icons, he worked for 15 years toward the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History. When Trump ran in 2016, he sensed the urgency, posting, "I’ve marched, protested, been beaten and arrested - all for the right to vote. Friends (gave) their lives. Honor their sacrifice. Vote." He refused to attend the inauguration because Trump wasn't a "legitimate president." He called him "a racist" after the "shithole countries" slur, and voted for impeachment: “When you see something that is not right, not just, not fair, you have a moral obligation to say something, to do something. Our children and their children will ask us, 'What did you do? What did you say?'"

He died of pancreatic cancer on July 17, 2020, at 80. Nancy Pelosi called him "one of the greatest heroes of American history...May his memory be an inspiration that moves us all to, in the face of injustice, make ‘good trouble, necessary trouble.'” This week, Congressional Black Caucus members honored his legacy by vowing to do the same and reading his works. "His words are more necessary today than ever," said Rep. Jennifer McClellan. "John Lewis understood just as Dr. King did he wasn’t going to reach the promised land of that more perfect union. But he fought for it."

Since his death, Dems have continued to reintroduce the John Lewis Voting Rights Advancement Act to restore key, GOP-trashed provisions of the 1965 Voting Rights Act. It has repeatedly stalled in Congress, and for now will likely continue to. But Lewis' colleagues vow to keep pushing for it, said Georgia Rep. Lucy McBath, "to honor his legacy with unshakeable determination to fight for what is right and what is just." "Freedom is not a state; it is an act," said Lewis. "It is not some enchanted garden perched high (where) we can finally sit down and rest. Freedom is the continuous action we all must take." While, he attested at a Stacey Abrams event the year before he died, finding joy. May he rest in peace and power.

To those who feel nothing seems to change: "You must be able and prepared to give until you cannot give any more. We must use our time and our space on this little planet that we call Earth to make a lasting contribution, to leave it a little better than we found it, and now that need is greater than ever before.” - John Lewis, near the end of his life.

- YouTube www.youtube.com

Taking a break from the awful to celebrate - remember that? - indefatigable civil rights icon, all-round mensch and former chicken preacher John Lewis, who died five years ago today after a lifetime of good trouble. The peerless "moral compass of Congress," now sorely lacking, Lewis never gave up seeking his "beloved community" even as he acknowledged he might never live in it. "Our struggle is not (of) a day, month or year," he said: "It is the struggle of a lifetime."

Over 60 years, Lewis' lifetime of struggle extended from student lunch-counter sit-ins, beatings as one of 13 original volunteers on Freedom Rides, founding and leading SNCC, speaking fire as the youngest organizer of the March in Washington and Bloody Sunday's seminal Selma march to, eventually, the halls of Congress, where he served 17 terms while persisting in making good trouble in ongoing fights for peace, immigrants, LGBTQ rights and voting rights that, he resolutely declared, “For generations we have marched, fought and even died for." Above all, "John believed in the power of ordinary people to do extraordinary things."

Born the trouble-making son of sharecroppers outside Troy, Alabama in 1940, he attended segregated public schools. As a boy, he wanted to be a minister, and famously practiced his oratory on the family chickens. Denied a library card for the color of his skin, he became a voracious reader. He was a teenager when he heard, riveted, Martin Luther King Jr. preaching on the radio. They met when Lewis was trying to become the first Black student at Alabama’s segregated Troy State University; he ultimately attended the American Baptist Theological Seminary and Nashville's Fisk University.

Along with Diane Nash and other members of the Nashville Student Movement, he began organizing sit-ins at whites-only lunch counters after four Black college students in Greensboro, N.C. first did it; there, staff refused to serve them but the students wouldn't leave, and then went back with more recruits. Lewis' first arrest came in February 1960 at age 20, when he sat down at a segregated Woolworth's lunch counter in Nashville. Angry white patrons beat and tried to remove him and his fellow protesters; when police finally arrived, they arrested the protesters.

“I didn't necessarily want to go to jail," he recalled in a 1973 interview. “But we knew (it) would rally the student community." And it did: By the end of the day 98 students were in jail, hundreds followed, and that spring Nashville lunch counters began serving Blacks. "Nashville prepared me," he said. "We grew up sitting down or sitting in. And we grew up very fast." Soon, Lewis was also traveling through a belligerent, still-segregated South as a Freedom Rider, enduring more beatings and arrests. Between 1960 and 1966, he was arrested at least 40 times; as a Congressman, he was arrested five more times.

As the 23-year-old head of SNCC, he gave a fiery speech at 1963's MLK Jr.-led March on Washington. Older fellow-organizers - Philip Randolph, 74, and James Farmer, Whitney Young, Roy Wilkins - urged him to tone it down; he scaled back critiques of JFK and dropped a "scorched earth" reference, but it was still potent. "To those who have said, 'Be patient'...We are tired. We are tired of being beaten by policemen, (of) seeing our people locked up in jail... How long can we be patient? We want our freedom and we want it now...We shall splinter the segregated South into a thousand pieces and put them together in an image of God and democracy.”

Two years later, hands tucked in his genteel tan overcoat, he led over 600 voting rights protesters over Selma's Edmund Pettus Bridge, named for a Ku Klux Klan leader, in what became known as Bloody Sunday. State troopers and "deputized" white thugs beat him so badly - still-chilling video here - they fractured his skull. Images of the brutality shocked a complacent nation, and eventually helped led to the Voting Rights Act of 1965. When he joined Pres. Obama at the site 55 years later, Lewis was still urging anyone who'd listen to "get in good trouble, necessary trouble, and help redeem the soul of America."

In 1981, Lewis was elected to the Atlanta City Council; in 1986, he won what became his longtime seat in Congress. He spent much of his career in the minority, but when Dems won the House in 2006, he became his party’s senior deputy whip. Humble, friendly, eloquent, he was revered as the "moral compass" of the House. His last arrest was in 2013 as one of 8 Dem lawmakers, including Keith Ellison and Al Green, arrested at a sit-in for immigration reform; police arrested 200 people for "disrupting" the street. Lewis posted a photo: "Arrest number 45." Always, he calmly insisted, "We will find a way to make a way out of no way.”

The last survivor of the civil rights icons, he worked for 15 years toward the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History. When Trump ran in 2016, he sensed the urgency, posting, "I’ve marched, protested, been beaten and arrested - all for the right to vote. Friends (gave) their lives. Honor their sacrifice. Vote." He refused to attend the inauguration because Trump wasn't a "legitimate president." He called him "a racist" after the "shithole countries" slur, and voted for impeachment: “When you see something that is not right, not just, not fair, you have a moral obligation to say something, to do something. Our children and their children will ask us, 'What did you do? What did you say?'"

He died of pancreatic cancer on July 17, 2020, at 80. Nancy Pelosi called him "one of the greatest heroes of American history...May his memory be an inspiration that moves us all to, in the face of injustice, make ‘good trouble, necessary trouble.'” This week, Congressional Black Caucus members honored his legacy by vowing to do the same and reading his works. "His words are more necessary today than ever," said Rep. Jennifer McClellan. "John Lewis understood just as Dr. King did he wasn’t going to reach the promised land of that more perfect union. But he fought for it."

Since his death, Dems have continued to reintroduce the John Lewis Voting Rights Advancement Act to restore key, GOP-trashed provisions of the 1965 Voting Rights Act. It has repeatedly stalled in Congress, and for now will likely continue to. But Lewis' colleagues vow to keep pushing for it, said Georgia Rep. Lucy McBath, "to honor his legacy with unshakeable determination to fight for what is right and what is just." "Freedom is not a state; it is an act," said Lewis. "It is not some enchanted garden perched high (where) we can finally sit down and rest. Freedom is the continuous action we all must take." While, he attested at a Stacey Abrams event the year before he died, finding joy. May he rest in peace and power.

To those who feel nothing seems to change: "You must be able and prepared to give until you cannot give any more. We must use our time and our space on this little planet that we call Earth to make a lasting contribution, to leave it a little better than we found it, and now that need is greater than ever before.” - John Lewis, near the end of his life.

- YouTube www.youtube.com