SUBSCRIBE TO OUR FREE NEWSLETTER

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

5

#000000

#FFFFFF

To donate by check, phone, or other method, see our More Ways to Give page.

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

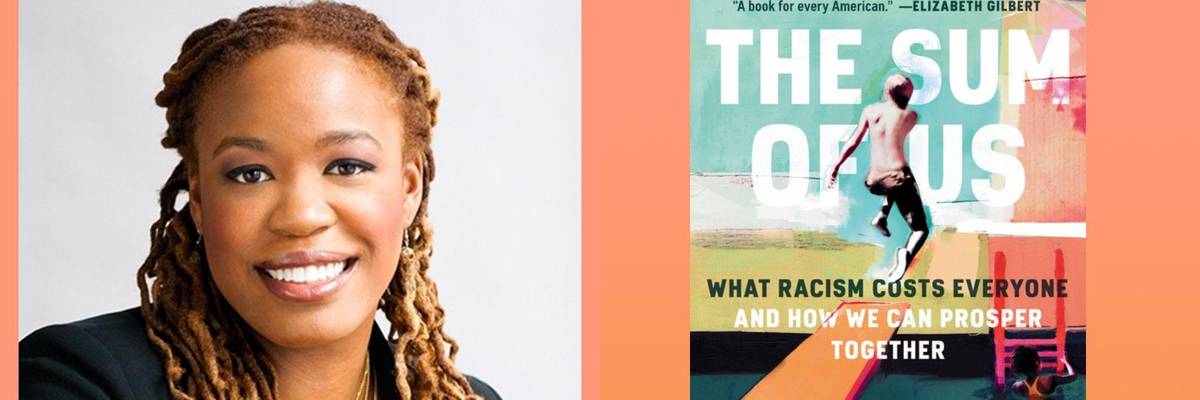

Heather McGhee's "The Sum of Us: What Racism Costs Everyone and How We Can Prosper Together"

As the Post-Gazette's book review editor since 2012, I assign far more reviews than I ever have to write. The biggest perk of the job is that I get to read without worrying about the deadline for writing reviews I impose on the army of colleagues and talented freelancers who do most of the heavy lifting.

This means I'm free to swoop in at the end of the year with abbreviated takes and recommendations of books in my column without taking space from reviewers who toil over far longer and more thoughtful reviews every week.

This year, the nonfiction book I've recommended the most to anyone who will listen is Heather McGhee's "The Sum of Us: What Racism Costs Everyone and How We Can Prosper Together."

The absorbing history of systemic racial discrimination in America showcases the decision of white officials during Jim Crow who resisted court orders to integrate public pools by draining them and filling them with cement.

This led to a boom in backyard pool construction in white communities. It is the perfect metaphor for social and economic policies in this country that included redlining, business loan discrimination against minority applicants, and other examples of the "zero-sum paradigm," as Ms. McGhee calls it. This discrimination has had negative ripple effects across the economy and has cost white people, whether they realize it, hundreds of billions, too. Prepare to be both infuriated and enlightened by an economic theorist who writes like a poet.

The most intellectually challenging book this year for me -- and arguably the most interesting, because I agreed with so much of what the writer had to say about specific hypocrisies of white saviors while disagreeing with much of its premise -- is John McWhorter's "Woke Racism: How a New Religion Has Betrayed Black America."

Mr. McWhorter, a linguistics professor at Columbia University, is an old-school Black progressive who doesn't hide his disdain for white liberals and what he considers their Black enablers in academia and the culture. He argues that the anti-racism movement of the "elected" is more performative than intellectually serious and that the white allies who provide the shock troops at universities and street rallies are just as gross as white supremacists because their virtue signaling hides their condescension. Fighting words can be found on practically every page along with cogent arguments, which is why it is should be read and discussed widely.

For three decades, Wil Haygood, a former staff writer at the Post-Gazette, the Boston Globe and The Washington Post, has been writing the kind of in-depth histories of American culture -- popular, legal and personal -- that the nation desperately needs. His latest is an instant classic because of the brilliant way he's able to put different aspects of our conflicted history into dialogue with each other: "Colorization: One Hundred Years of Black Films in a White World," an omnivorous chronicle of the shifting racial politics of the movie business and how it came to be.

Whether discussing cinema pioneer Oscar Micheaux, Spike Lee's Malcolm X-inspired nationalism, Marvel's "Black Panther," or Ava DuVernay and Jordan Peele's centering of the Black experience as the non-negotiable ground of their cinematic vision, Mr. Haygood has thought about it. As someone who was deeply involved in the making of the acclaimed film "The Butler," he understands the challenges of being a Black creative in a business that prefers to commodify Black pain for fun and profit.

Mary Roach is the best popular science writer alive because she's able to capture the spectacle of modern existence in all of its dazzling absurdity. In "Fuzz: When Nature Breaks the Law," she turns her attention to that weird intersection where humans and wildlife meet and where nature gets the upper hand in the ensuing conflicts among people, bears, cougars, trees and larcenous birds.

"The Council of Animals," a short novel by Nick McDonell, takes humanity's conflict with nature to the next level. After most humans have been wiped out by some apocalyptic catastrophe of our own doing, a remnant of humans have no idea their fate is being debated by a cadre of animals who have to decide whether the species should be allowed to live or be wiped out by the creatures who were once their food, servants and pawns.

Despite a rushed and problematic ending that didn't sit well with me, it was one of the most enjoyable novels of the summer.

I'm a latecomer to the fiction of George Saunders. His latest work, "A Swim in a Pond in the Rain: In Which Four Russians Give a Master Class on Writing, Reading, and Life," is one of three books on writing any aspiring writer will ever need. Mr. Saunders argues that writing fiction is a great moral undertaking and not just literary high jinks for its own sake.

He teaches a master's of fine arts writing class at Syracuse University, where he instructs students to read and deconstruct Chekhov, Gogol, Turgenev and Tolstoy's short stories. This book is effectively the course, complete with questions at the end of each chapter that prompt readers to go deeper.

The best novel I've come across during a year in which I'm admittedly behind in my fiction reading is Colson Whitehead's "Harlem Shuffle," which is a welcome change of pace in terms of subject matter for the two-time Pulitzer winner.

This one is a tale of a heist at a historic Harlem hotel gone wrong. It takes place in the early 1960s and centers on the double life of a furniture salesman whose desire for middle-class respectability clashes with his desire for a big score that will lift him to the next level. Mr. Whitehead's mastery of the details of that era are a wonder to behold. It would not shock me if he becomes a finalist for his third Pulitzer with "Harlem Shuffle."

The pandemic seems to have produced a new generation of fans for "The Sopranos," HBO's biggest hit to date. "Woke up This Morning: The Definitive Oral History of 'The Sopranos'" builds on the popular podcast hosted by stars Michael Imperioli (Christopher Moltisanti) and Steve Schirripa (Bobby Baccalieri).

Co-written with Philip Lerman, the book reflects their bonds of affection as they dissect a cultural phenomenon they're still amazed they played a role in. They can't answer every question, but they're not shy about sharing their theories. "Woke up This Morning" feels like an extra season of that groundbreaking series distilled into nearly 500 pages.

Everyone who knows me knows I'm a big fan of graphic novels. Three released this year absolutely blew my mind. "The Stringer," written by Ted Rall and illustrated by Pablo Callejo, is the tale of a cynical war correspondent who uses his insight to start new wars or stir up old ones so he always has a conflict to cover.

"A Revolution in Three Acts: The Radical Vaudeville of Bert Williams, Eva Tanguay and Julian Eltinge" by David Hajdu and John Carey is the surprise of the year for me because there's so much I didn't know or suspect about early 20th-century mass entertainment and its impact on how America saw itself.

These three iconic performers -- the Black star of minstrel shows, the female performer who rejects her gender and the male who identifies as female -- navigate vaudeville during the twilight of the Victorian age trying to find their place in society. The results of their artistic pursuits are tragic, comic and always poignant.

My favorite graphic novel this year is about one of my musical heroes. "Leonard Cohen on a Wire" is written and illustrated by Philippe Girard. The book, which is gorgeously illustrated with bold but cartoonish brio, chronicles the life of the singer/ songwriter from his early days in Montreal through his knocking around Greenwich Village in the '60s, his many love affairs, his time at a Zen Buddhist monastery and his triumphant return to the stage just a few years before he died. Cohen obsessives will love this illustrated biography.

All readers need a book they can dip into a few pages at a time because the concepts it explores are so heavy. My biggest brain-teasing read this year is "The Disordered Cosmos: A Journey Into Dark Matter, Spacetime, & Dreams Deferred" by Chanda Prescod-Weinstein.

Before reading "The Disordered Cosmos," I never suspected that Black feminism, dark matter and quantum realities could intersect at any point, but Ms. Prescod-Weinstein has made a believer of me with this beautiful memoir that is part meditation on cosmic mysteries and what it's like to be a scientist with many identities in the world.

I'm still reading Clinton Heylin's magisterial "The Double Life of Bob Dylan: A Restless, Hungry Feeling (1941-1966)." This book is almost too rich because the author has unearthed new material and has unrestricted access to Dylan's archives that haven't been available to other scholars.

Short of Dylan giving us a truthful account of his early days (not likely), this will remain the definitive account of his origin story for decades.

Dear Common Dreams reader, The U.S. is on a fast track to authoritarianism like nothing I've ever seen. Meanwhile, corporate news outlets are utterly capitulating to Trump, twisting their coverage to avoid drawing his ire while lining up to stuff cash in his pockets. That's why I believe that Common Dreams is doing the best and most consequential reporting that we've ever done. Our small but mighty team is a progressive reporting powerhouse, covering the news every day that the corporate media never will. Our mission has always been simple: To inform. To inspire. And to ignite change for the common good. Now here's the key piece that I want all our readers to understand: None of this would be possible without your financial support. That's not just some fundraising cliche. It's the absolute and literal truth. We don't accept corporate advertising and never will. We don't have a paywall because we don't think people should be blocked from critical news based on their ability to pay. Everything we do is funded by the donations of readers like you. Will you donate now to help power the nonprofit, independent reporting of Common Dreams? Thank you for being a vital member of our community. Together, we can keep independent journalism alive when it’s needed most. - Craig Brown, Co-founder |

As the Post-Gazette's book review editor since 2012, I assign far more reviews than I ever have to write. The biggest perk of the job is that I get to read without worrying about the deadline for writing reviews I impose on the army of colleagues and talented freelancers who do most of the heavy lifting.

This means I'm free to swoop in at the end of the year with abbreviated takes and recommendations of books in my column without taking space from reviewers who toil over far longer and more thoughtful reviews every week.

This year, the nonfiction book I've recommended the most to anyone who will listen is Heather McGhee's "The Sum of Us: What Racism Costs Everyone and How We Can Prosper Together."

The absorbing history of systemic racial discrimination in America showcases the decision of white officials during Jim Crow who resisted court orders to integrate public pools by draining them and filling them with cement.

This led to a boom in backyard pool construction in white communities. It is the perfect metaphor for social and economic policies in this country that included redlining, business loan discrimination against minority applicants, and other examples of the "zero-sum paradigm," as Ms. McGhee calls it. This discrimination has had negative ripple effects across the economy and has cost white people, whether they realize it, hundreds of billions, too. Prepare to be both infuriated and enlightened by an economic theorist who writes like a poet.

The most intellectually challenging book this year for me -- and arguably the most interesting, because I agreed with so much of what the writer had to say about specific hypocrisies of white saviors while disagreeing with much of its premise -- is John McWhorter's "Woke Racism: How a New Religion Has Betrayed Black America."

Mr. McWhorter, a linguistics professor at Columbia University, is an old-school Black progressive who doesn't hide his disdain for white liberals and what he considers their Black enablers in academia and the culture. He argues that the anti-racism movement of the "elected" is more performative than intellectually serious and that the white allies who provide the shock troops at universities and street rallies are just as gross as white supremacists because their virtue signaling hides their condescension. Fighting words can be found on practically every page along with cogent arguments, which is why it is should be read and discussed widely.

For three decades, Wil Haygood, a former staff writer at the Post-Gazette, the Boston Globe and The Washington Post, has been writing the kind of in-depth histories of American culture -- popular, legal and personal -- that the nation desperately needs. His latest is an instant classic because of the brilliant way he's able to put different aspects of our conflicted history into dialogue with each other: "Colorization: One Hundred Years of Black Films in a White World," an omnivorous chronicle of the shifting racial politics of the movie business and how it came to be.

Whether discussing cinema pioneer Oscar Micheaux, Spike Lee's Malcolm X-inspired nationalism, Marvel's "Black Panther," or Ava DuVernay and Jordan Peele's centering of the Black experience as the non-negotiable ground of their cinematic vision, Mr. Haygood has thought about it. As someone who was deeply involved in the making of the acclaimed film "The Butler," he understands the challenges of being a Black creative in a business that prefers to commodify Black pain for fun and profit.

Mary Roach is the best popular science writer alive because she's able to capture the spectacle of modern existence in all of its dazzling absurdity. In "Fuzz: When Nature Breaks the Law," she turns her attention to that weird intersection where humans and wildlife meet and where nature gets the upper hand in the ensuing conflicts among people, bears, cougars, trees and larcenous birds.

"The Council of Animals," a short novel by Nick McDonell, takes humanity's conflict with nature to the next level. After most humans have been wiped out by some apocalyptic catastrophe of our own doing, a remnant of humans have no idea their fate is being debated by a cadre of animals who have to decide whether the species should be allowed to live or be wiped out by the creatures who were once their food, servants and pawns.

Despite a rushed and problematic ending that didn't sit well with me, it was one of the most enjoyable novels of the summer.

I'm a latecomer to the fiction of George Saunders. His latest work, "A Swim in a Pond in the Rain: In Which Four Russians Give a Master Class on Writing, Reading, and Life," is one of three books on writing any aspiring writer will ever need. Mr. Saunders argues that writing fiction is a great moral undertaking and not just literary high jinks for its own sake.

He teaches a master's of fine arts writing class at Syracuse University, where he instructs students to read and deconstruct Chekhov, Gogol, Turgenev and Tolstoy's short stories. This book is effectively the course, complete with questions at the end of each chapter that prompt readers to go deeper.

The best novel I've come across during a year in which I'm admittedly behind in my fiction reading is Colson Whitehead's "Harlem Shuffle," which is a welcome change of pace in terms of subject matter for the two-time Pulitzer winner.

This one is a tale of a heist at a historic Harlem hotel gone wrong. It takes place in the early 1960s and centers on the double life of a furniture salesman whose desire for middle-class respectability clashes with his desire for a big score that will lift him to the next level. Mr. Whitehead's mastery of the details of that era are a wonder to behold. It would not shock me if he becomes a finalist for his third Pulitzer with "Harlem Shuffle."

The pandemic seems to have produced a new generation of fans for "The Sopranos," HBO's biggest hit to date. "Woke up This Morning: The Definitive Oral History of 'The Sopranos'" builds on the popular podcast hosted by stars Michael Imperioli (Christopher Moltisanti) and Steve Schirripa (Bobby Baccalieri).

Co-written with Philip Lerman, the book reflects their bonds of affection as they dissect a cultural phenomenon they're still amazed they played a role in. They can't answer every question, but they're not shy about sharing their theories. "Woke up This Morning" feels like an extra season of that groundbreaking series distilled into nearly 500 pages.

Everyone who knows me knows I'm a big fan of graphic novels. Three released this year absolutely blew my mind. "The Stringer," written by Ted Rall and illustrated by Pablo Callejo, is the tale of a cynical war correspondent who uses his insight to start new wars or stir up old ones so he always has a conflict to cover.

"A Revolution in Three Acts: The Radical Vaudeville of Bert Williams, Eva Tanguay and Julian Eltinge" by David Hajdu and John Carey is the surprise of the year for me because there's so much I didn't know or suspect about early 20th-century mass entertainment and its impact on how America saw itself.

These three iconic performers -- the Black star of minstrel shows, the female performer who rejects her gender and the male who identifies as female -- navigate vaudeville during the twilight of the Victorian age trying to find their place in society. The results of their artistic pursuits are tragic, comic and always poignant.

My favorite graphic novel this year is about one of my musical heroes. "Leonard Cohen on a Wire" is written and illustrated by Philippe Girard. The book, which is gorgeously illustrated with bold but cartoonish brio, chronicles the life of the singer/ songwriter from his early days in Montreal through his knocking around Greenwich Village in the '60s, his many love affairs, his time at a Zen Buddhist monastery and his triumphant return to the stage just a few years before he died. Cohen obsessives will love this illustrated biography.

All readers need a book they can dip into a few pages at a time because the concepts it explores are so heavy. My biggest brain-teasing read this year is "The Disordered Cosmos: A Journey Into Dark Matter, Spacetime, & Dreams Deferred" by Chanda Prescod-Weinstein.

Before reading "The Disordered Cosmos," I never suspected that Black feminism, dark matter and quantum realities could intersect at any point, but Ms. Prescod-Weinstein has made a believer of me with this beautiful memoir that is part meditation on cosmic mysteries and what it's like to be a scientist with many identities in the world.

I'm still reading Clinton Heylin's magisterial "The Double Life of Bob Dylan: A Restless, Hungry Feeling (1941-1966)." This book is almost too rich because the author has unearthed new material and has unrestricted access to Dylan's archives that haven't been available to other scholars.

Short of Dylan giving us a truthful account of his early days (not likely), this will remain the definitive account of his origin story for decades.

As the Post-Gazette's book review editor since 2012, I assign far more reviews than I ever have to write. The biggest perk of the job is that I get to read without worrying about the deadline for writing reviews I impose on the army of colleagues and talented freelancers who do most of the heavy lifting.

This means I'm free to swoop in at the end of the year with abbreviated takes and recommendations of books in my column without taking space from reviewers who toil over far longer and more thoughtful reviews every week.

This year, the nonfiction book I've recommended the most to anyone who will listen is Heather McGhee's "The Sum of Us: What Racism Costs Everyone and How We Can Prosper Together."

The absorbing history of systemic racial discrimination in America showcases the decision of white officials during Jim Crow who resisted court orders to integrate public pools by draining them and filling them with cement.

This led to a boom in backyard pool construction in white communities. It is the perfect metaphor for social and economic policies in this country that included redlining, business loan discrimination against minority applicants, and other examples of the "zero-sum paradigm," as Ms. McGhee calls it. This discrimination has had negative ripple effects across the economy and has cost white people, whether they realize it, hundreds of billions, too. Prepare to be both infuriated and enlightened by an economic theorist who writes like a poet.

The most intellectually challenging book this year for me -- and arguably the most interesting, because I agreed with so much of what the writer had to say about specific hypocrisies of white saviors while disagreeing with much of its premise -- is John McWhorter's "Woke Racism: How a New Religion Has Betrayed Black America."

Mr. McWhorter, a linguistics professor at Columbia University, is an old-school Black progressive who doesn't hide his disdain for white liberals and what he considers their Black enablers in academia and the culture. He argues that the anti-racism movement of the "elected" is more performative than intellectually serious and that the white allies who provide the shock troops at universities and street rallies are just as gross as white supremacists because their virtue signaling hides their condescension. Fighting words can be found on practically every page along with cogent arguments, which is why it is should be read and discussed widely.

For three decades, Wil Haygood, a former staff writer at the Post-Gazette, the Boston Globe and The Washington Post, has been writing the kind of in-depth histories of American culture -- popular, legal and personal -- that the nation desperately needs. His latest is an instant classic because of the brilliant way he's able to put different aspects of our conflicted history into dialogue with each other: "Colorization: One Hundred Years of Black Films in a White World," an omnivorous chronicle of the shifting racial politics of the movie business and how it came to be.

Whether discussing cinema pioneer Oscar Micheaux, Spike Lee's Malcolm X-inspired nationalism, Marvel's "Black Panther," or Ava DuVernay and Jordan Peele's centering of the Black experience as the non-negotiable ground of their cinematic vision, Mr. Haygood has thought about it. As someone who was deeply involved in the making of the acclaimed film "The Butler," he understands the challenges of being a Black creative in a business that prefers to commodify Black pain for fun and profit.

Mary Roach is the best popular science writer alive because she's able to capture the spectacle of modern existence in all of its dazzling absurdity. In "Fuzz: When Nature Breaks the Law," she turns her attention to that weird intersection where humans and wildlife meet and where nature gets the upper hand in the ensuing conflicts among people, bears, cougars, trees and larcenous birds.

"The Council of Animals," a short novel by Nick McDonell, takes humanity's conflict with nature to the next level. After most humans have been wiped out by some apocalyptic catastrophe of our own doing, a remnant of humans have no idea their fate is being debated by a cadre of animals who have to decide whether the species should be allowed to live or be wiped out by the creatures who were once their food, servants and pawns.

Despite a rushed and problematic ending that didn't sit well with me, it was one of the most enjoyable novels of the summer.

I'm a latecomer to the fiction of George Saunders. His latest work, "A Swim in a Pond in the Rain: In Which Four Russians Give a Master Class on Writing, Reading, and Life," is one of three books on writing any aspiring writer will ever need. Mr. Saunders argues that writing fiction is a great moral undertaking and not just literary high jinks for its own sake.

He teaches a master's of fine arts writing class at Syracuse University, where he instructs students to read and deconstruct Chekhov, Gogol, Turgenev and Tolstoy's short stories. This book is effectively the course, complete with questions at the end of each chapter that prompt readers to go deeper.

The best novel I've come across during a year in which I'm admittedly behind in my fiction reading is Colson Whitehead's "Harlem Shuffle," which is a welcome change of pace in terms of subject matter for the two-time Pulitzer winner.

This one is a tale of a heist at a historic Harlem hotel gone wrong. It takes place in the early 1960s and centers on the double life of a furniture salesman whose desire for middle-class respectability clashes with his desire for a big score that will lift him to the next level. Mr. Whitehead's mastery of the details of that era are a wonder to behold. It would not shock me if he becomes a finalist for his third Pulitzer with "Harlem Shuffle."

The pandemic seems to have produced a new generation of fans for "The Sopranos," HBO's biggest hit to date. "Woke up This Morning: The Definitive Oral History of 'The Sopranos'" builds on the popular podcast hosted by stars Michael Imperioli (Christopher Moltisanti) and Steve Schirripa (Bobby Baccalieri).

Co-written with Philip Lerman, the book reflects their bonds of affection as they dissect a cultural phenomenon they're still amazed they played a role in. They can't answer every question, but they're not shy about sharing their theories. "Woke up This Morning" feels like an extra season of that groundbreaking series distilled into nearly 500 pages.

Everyone who knows me knows I'm a big fan of graphic novels. Three released this year absolutely blew my mind. "The Stringer," written by Ted Rall and illustrated by Pablo Callejo, is the tale of a cynical war correspondent who uses his insight to start new wars or stir up old ones so he always has a conflict to cover.

"A Revolution in Three Acts: The Radical Vaudeville of Bert Williams, Eva Tanguay and Julian Eltinge" by David Hajdu and John Carey is the surprise of the year for me because there's so much I didn't know or suspect about early 20th-century mass entertainment and its impact on how America saw itself.

These three iconic performers -- the Black star of minstrel shows, the female performer who rejects her gender and the male who identifies as female -- navigate vaudeville during the twilight of the Victorian age trying to find their place in society. The results of their artistic pursuits are tragic, comic and always poignant.

My favorite graphic novel this year is about one of my musical heroes. "Leonard Cohen on a Wire" is written and illustrated by Philippe Girard. The book, which is gorgeously illustrated with bold but cartoonish brio, chronicles the life of the singer/ songwriter from his early days in Montreal through his knocking around Greenwich Village in the '60s, his many love affairs, his time at a Zen Buddhist monastery and his triumphant return to the stage just a few years before he died. Cohen obsessives will love this illustrated biography.

All readers need a book they can dip into a few pages at a time because the concepts it explores are so heavy. My biggest brain-teasing read this year is "The Disordered Cosmos: A Journey Into Dark Matter, Spacetime, & Dreams Deferred" by Chanda Prescod-Weinstein.

Before reading "The Disordered Cosmos," I never suspected that Black feminism, dark matter and quantum realities could intersect at any point, but Ms. Prescod-Weinstein has made a believer of me with this beautiful memoir that is part meditation on cosmic mysteries and what it's like to be a scientist with many identities in the world.

I'm still reading Clinton Heylin's magisterial "The Double Life of Bob Dylan: A Restless, Hungry Feeling (1941-1966)." This book is almost too rich because the author has unearthed new material and has unrestricted access to Dylan's archives that haven't been available to other scholars.

Short of Dylan giving us a truthful account of his early days (not likely), this will remain the definitive account of his origin story for decades.