SUBSCRIBE TO OUR FREE NEWSLETTER

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

5

#000000

#FFFFFF

To donate by check, phone, or other method, see our More Ways to Give page.

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

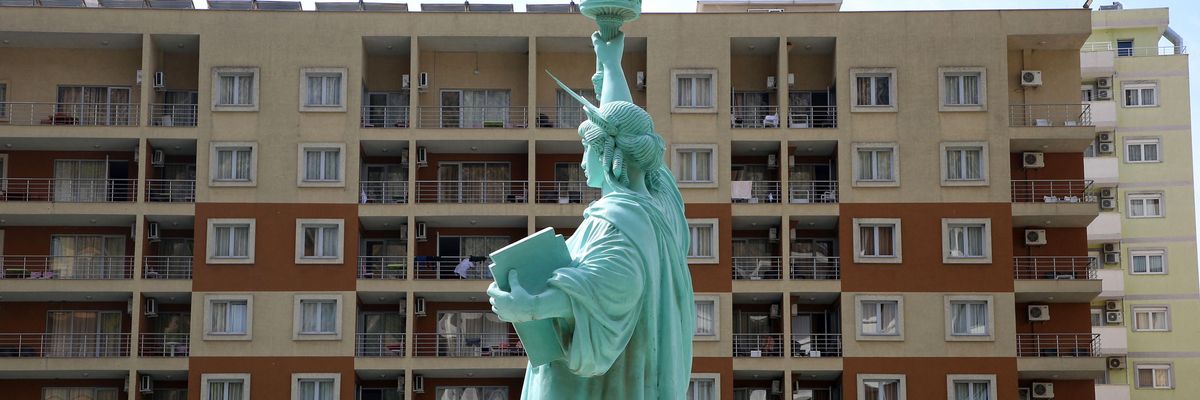

A mock-up of the Statue of Liberty is seen outside a resort in the coastal city of Shengjin, on Sept. 11, 2021, where people evacuated from Afghanistan are sheltered. A provision in the National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2022, recently passed by the House of Representatives, calls for the creation of an Afghanistan War Commission. (Photo by GENT SHKULLAKU/AFP via Getty Images)

Here in Red Sox Nation, baseball fans are given to wearing T-shirts that read "Yankees Suck!" Another local sentiment, perhaps even more widespread, goes like this: "Congress Sucks!"

All the more reason, therefore, to celebrate those occasions when Congress does the right thing. Such a moment is now upon us. A provision in the National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2022, recently passed by the House of Representatives, calls for the creation of an "Afghanistan War Commission." Apparently, the Senate is primed to concur, with the final bill expected to reach President Biden's desk after the New Year. All of that qualifies as cause for celebration.

A distinguishing feature of the "forever wars" launched in the aftermath of 9/11 has been a near-total absence of political and military accountability. Now Congress appears poised to subject the longest of those wars to critical assessment. Crucially, the commission's proposed mandate extends well beyond the massively mismanaged and embarrassing evacuation of Kabul in August that marked the 20-year war's dismal conclusion. It will instead subject the entire war to a comprehensive examination. Included in the commission's mandate, according to the draft legislation, are "all matters relating to combat operations, reconstruction and security force assistance activities, intelligence activities, and diplomatic activities" spanning the entire period from June 1, 2001 to Aug. 30, 2021.

The legislation specifically tasks the commission with examining "key strategic, diplomatic, and operational decisions" during the war itself along with "decisions, assessments, and events that preceded" the conflict. It also charges the commission to "develop a series of lessons learned and recommendations for the way forward that will inform future decisions by Congress and policymakers throughout the United States Government."

So the commission's mandate is simultaneously specific and appropriately capacious. There remains but a single potential fly in the ointment: the selection of the 16 commissioners, including two co-chairs, who along with an executive director will undertake this crucially needed investigation.

Leading members of Congress from both parties will determine the specific composition of the commission. The chair of the Senate Armed Services Committee gets one appointment as does the committee's ranking member. So, too, do the chair and ranking member of the House equivalent -- and so on, with chairs and ranking members of the foreign affairs and intelligence committees each allowed an appointment. The majority and minority leaders of both houses also get one pick.

So just about anyone who is anyone on Capitol Hill gets a bite of the apple -- not necessarily the best way to assemble a commission consisting of individuals who possess the right credentials and are motivated to dig deep in pursuit of truth.

The draft legislation is admirably clear on who is not eligible to serve: no former cabinet officials, no retired four-star military officers, and no one who was "the sole owner or had a majority stake in a company that held any United States or coalition defense contract providing goods or services" -- in plain language, no mercenaries and no merchants of death.

That's good as far as it goes. But producing the requisite lessons learned and recommendations -- if they are to be worth serious consideration -- will entail more than genuflecting before the gods of bipartisanship and diversity. Success will require a willingness to demonstrate both intellectual and moral fortitude.

Courtesy of Supreme Court Justice Sonia Sotomayor, the term "stench" has recently achieved prominence in the lexicon of American politics. To anyone with even a minimally acute sense of smell, the stench stemming from the Afghanistan War over 20 years is considerable. Poking around in the residue in pursuit of truth will require strong stomachs. But that search for uncomfortable truths is precisely what members of the Afghanistan War Commission must be prepared to undertake -- and what the troops who served and sacrificed in Afghanistan are owed. Otherwise, commission members will be wasting their time and failing the country.

So assembling the slate of commission nominees is crucially important. For Congress to falter in that undertaking would be to undermine the entire enterprise. And that would constitute not only a missed opportunity but something close to a betrayal.

Dear Common Dreams reader, The U.S. is on a fast track to authoritarianism like nothing I've ever seen. Meanwhile, corporate news outlets are utterly capitulating to Trump, twisting their coverage to avoid drawing his ire while lining up to stuff cash in his pockets. That's why I believe that Common Dreams is doing the best and most consequential reporting that we've ever done. Our small but mighty team is a progressive reporting powerhouse, covering the news every day that the corporate media never will. Our mission has always been simple: To inform. To inspire. And to ignite change for the common good. Now here's the key piece that I want all our readers to understand: None of this would be possible without your financial support. That's not just some fundraising cliche. It's the absolute and literal truth. We don't accept corporate advertising and never will. We don't have a paywall because we don't think people should be blocked from critical news based on their ability to pay. Everything we do is funded by the donations of readers like you. Will you donate now to help power the nonprofit, independent reporting of Common Dreams? Thank you for being a vital member of our community. Together, we can keep independent journalism alive when it’s needed most. - Craig Brown, Co-founder |

Here in Red Sox Nation, baseball fans are given to wearing T-shirts that read "Yankees Suck!" Another local sentiment, perhaps even more widespread, goes like this: "Congress Sucks!"

All the more reason, therefore, to celebrate those occasions when Congress does the right thing. Such a moment is now upon us. A provision in the National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2022, recently passed by the House of Representatives, calls for the creation of an "Afghanistan War Commission." Apparently, the Senate is primed to concur, with the final bill expected to reach President Biden's desk after the New Year. All of that qualifies as cause for celebration.

A distinguishing feature of the "forever wars" launched in the aftermath of 9/11 has been a near-total absence of political and military accountability. Now Congress appears poised to subject the longest of those wars to critical assessment. Crucially, the commission's proposed mandate extends well beyond the massively mismanaged and embarrassing evacuation of Kabul in August that marked the 20-year war's dismal conclusion. It will instead subject the entire war to a comprehensive examination. Included in the commission's mandate, according to the draft legislation, are "all matters relating to combat operations, reconstruction and security force assistance activities, intelligence activities, and diplomatic activities" spanning the entire period from June 1, 2001 to Aug. 30, 2021.

The legislation specifically tasks the commission with examining "key strategic, diplomatic, and operational decisions" during the war itself along with "decisions, assessments, and events that preceded" the conflict. It also charges the commission to "develop a series of lessons learned and recommendations for the way forward that will inform future decisions by Congress and policymakers throughout the United States Government."

So the commission's mandate is simultaneously specific and appropriately capacious. There remains but a single potential fly in the ointment: the selection of the 16 commissioners, including two co-chairs, who along with an executive director will undertake this crucially needed investigation.

Leading members of Congress from both parties will determine the specific composition of the commission. The chair of the Senate Armed Services Committee gets one appointment as does the committee's ranking member. So, too, do the chair and ranking member of the House equivalent -- and so on, with chairs and ranking members of the foreign affairs and intelligence committees each allowed an appointment. The majority and minority leaders of both houses also get one pick.

So just about anyone who is anyone on Capitol Hill gets a bite of the apple -- not necessarily the best way to assemble a commission consisting of individuals who possess the right credentials and are motivated to dig deep in pursuit of truth.

The draft legislation is admirably clear on who is not eligible to serve: no former cabinet officials, no retired four-star military officers, and no one who was "the sole owner or had a majority stake in a company that held any United States or coalition defense contract providing goods or services" -- in plain language, no mercenaries and no merchants of death.

That's good as far as it goes. But producing the requisite lessons learned and recommendations -- if they are to be worth serious consideration -- will entail more than genuflecting before the gods of bipartisanship and diversity. Success will require a willingness to demonstrate both intellectual and moral fortitude.

Courtesy of Supreme Court Justice Sonia Sotomayor, the term "stench" has recently achieved prominence in the lexicon of American politics. To anyone with even a minimally acute sense of smell, the stench stemming from the Afghanistan War over 20 years is considerable. Poking around in the residue in pursuit of truth will require strong stomachs. But that search for uncomfortable truths is precisely what members of the Afghanistan War Commission must be prepared to undertake -- and what the troops who served and sacrificed in Afghanistan are owed. Otherwise, commission members will be wasting their time and failing the country.

So assembling the slate of commission nominees is crucially important. For Congress to falter in that undertaking would be to undermine the entire enterprise. And that would constitute not only a missed opportunity but something close to a betrayal.

Here in Red Sox Nation, baseball fans are given to wearing T-shirts that read "Yankees Suck!" Another local sentiment, perhaps even more widespread, goes like this: "Congress Sucks!"

All the more reason, therefore, to celebrate those occasions when Congress does the right thing. Such a moment is now upon us. A provision in the National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2022, recently passed by the House of Representatives, calls for the creation of an "Afghanistan War Commission." Apparently, the Senate is primed to concur, with the final bill expected to reach President Biden's desk after the New Year. All of that qualifies as cause for celebration.

A distinguishing feature of the "forever wars" launched in the aftermath of 9/11 has been a near-total absence of political and military accountability. Now Congress appears poised to subject the longest of those wars to critical assessment. Crucially, the commission's proposed mandate extends well beyond the massively mismanaged and embarrassing evacuation of Kabul in August that marked the 20-year war's dismal conclusion. It will instead subject the entire war to a comprehensive examination. Included in the commission's mandate, according to the draft legislation, are "all matters relating to combat operations, reconstruction and security force assistance activities, intelligence activities, and diplomatic activities" spanning the entire period from June 1, 2001 to Aug. 30, 2021.

The legislation specifically tasks the commission with examining "key strategic, diplomatic, and operational decisions" during the war itself along with "decisions, assessments, and events that preceded" the conflict. It also charges the commission to "develop a series of lessons learned and recommendations for the way forward that will inform future decisions by Congress and policymakers throughout the United States Government."

So the commission's mandate is simultaneously specific and appropriately capacious. There remains but a single potential fly in the ointment: the selection of the 16 commissioners, including two co-chairs, who along with an executive director will undertake this crucially needed investigation.

Leading members of Congress from both parties will determine the specific composition of the commission. The chair of the Senate Armed Services Committee gets one appointment as does the committee's ranking member. So, too, do the chair and ranking member of the House equivalent -- and so on, with chairs and ranking members of the foreign affairs and intelligence committees each allowed an appointment. The majority and minority leaders of both houses also get one pick.

So just about anyone who is anyone on Capitol Hill gets a bite of the apple -- not necessarily the best way to assemble a commission consisting of individuals who possess the right credentials and are motivated to dig deep in pursuit of truth.

The draft legislation is admirably clear on who is not eligible to serve: no former cabinet officials, no retired four-star military officers, and no one who was "the sole owner or had a majority stake in a company that held any United States or coalition defense contract providing goods or services" -- in plain language, no mercenaries and no merchants of death.

That's good as far as it goes. But producing the requisite lessons learned and recommendations -- if they are to be worth serious consideration -- will entail more than genuflecting before the gods of bipartisanship and diversity. Success will require a willingness to demonstrate both intellectual and moral fortitude.

Courtesy of Supreme Court Justice Sonia Sotomayor, the term "stench" has recently achieved prominence in the lexicon of American politics. To anyone with even a minimally acute sense of smell, the stench stemming from the Afghanistan War over 20 years is considerable. Poking around in the residue in pursuit of truth will require strong stomachs. But that search for uncomfortable truths is precisely what members of the Afghanistan War Commission must be prepared to undertake -- and what the troops who served and sacrificed in Afghanistan are owed. Otherwise, commission members will be wasting their time and failing the country.

So assembling the slate of commission nominees is crucially important. For Congress to falter in that undertaking would be to undermine the entire enterprise. And that would constitute not only a missed opportunity but something close to a betrayal.