On September 11, I was woken in my California home with an urgent call from Martha Honey, then-director of Foreign Policy In Focus, telling me to turn on my television to view the burning towers.

I watched them both fall, along with the announcements of the attack on the Pentagon and crash in Pennsylvania. I had visited war zones on several continents, but nothing could have prepared me for the horror inflicted upon my own country. Unfortunately, I barely allowed myself to grieve over the horror due to my fear--which ended up being tragically prescient--of the far greater terror my government would unleash on the Middle East as a response.

The more the United States had militarized the region, the less secure the American people had become.

As a Middle East specialist, I engaged in scores of interviews and wrote a number of widely circulated articles in the days, weeks and months that followed. Both out of respect for those killed and their loved ones as well as my own deep-seated feelings of anger and horror, I did not mince words regarding the perpetrators of the attacks and their supporters. I even defended the right of the United States and its allies to engage in (a limited and targeted) military response to the very real threat posed by al-Qaeda. However, I also thought that it was critical to examine what may have motivated the horrific attacks, which I found important not only in preventing future terrorism, but also to avoid policies that could further exacerbate the threat.

My argument was that the more the United States had militarized the region, the less secure the American people had become. I noted how all the sophisticated weaponry, brave soldiers, and brilliant military leadership the United States possessed would do little good if there were hundreds of millions of people in the Middle East and beyond who hated us. Even though only a small percentage of the population supported Osama bin Laden's methods, I argued, there would still be enough people to maintain dangerous terrorist networks as long as his grievances resonated with large numbers of people.

I went on to explain how, as most Muslims recognized, bin Laden was not an authority on Islam. He was, however, a businessman by training, who--like any shrewd businessman--knew how to take a popular fear or desire and use it to sell a product: in this case, anti-American terrorism. The grievances expressed in his manifestos--the ongoing U.S. military presence in the Gulf, the humanitarian consequences of the U.S.-led sanctions against Iraq, U.S. support for the Israeli government, and U.S. backing of autocratic Arab regimes--had widespread appeal in that part of the world. I quoted British novelist John le Carre's observation that, "What America longs for at this moment, even more that retribution, is more friends and fewer enemies."

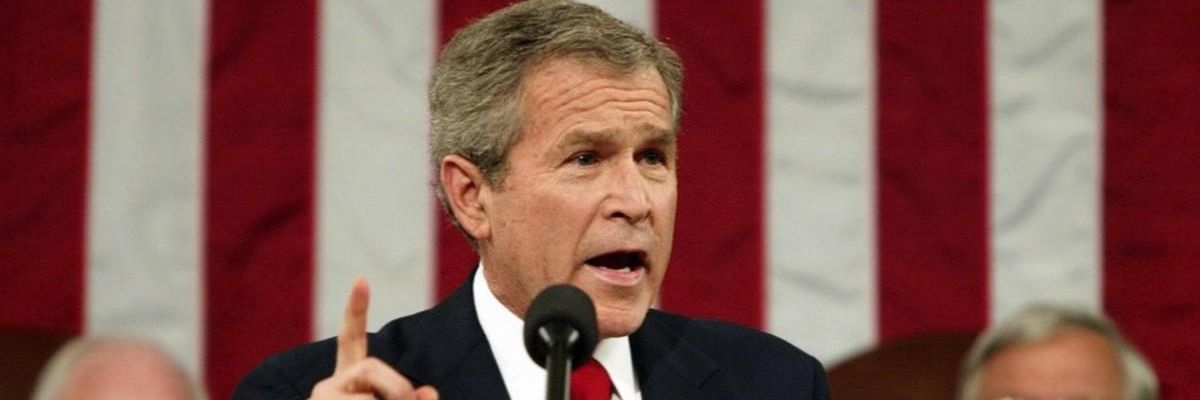

I reiterated how there was nothing karmic about the events of 9/11, but that history had demonstrated how the United States did not become a target for terrorists because of its values, as President Bush and others claimed, but because it had strayed from its professed values of freedom, democracy, and rule of law in implementing its policies in the Middle East. Furthermore, I argued that a policy based more on the promotion of human rights, international law, and sustainable development, and less on arms transfers, air strikes, punitive sanctions, and support for occupation armies and dictatorial governments, would make Americans a lot safer.

I repeatedly emphasized that, whatever the failings of a government in its foreign policy, no country deserves to experience such a large-scale loss of innocent lives as the United States experienced on 9/11. Yet I also stressed that the hope of stopping extremists who might resort to such heinous acts in the future rested in part on the willingness of Americans to recognize what gave rise to what veteran journalist Robert Fisk described as "the wickedness and awesome cruelty of a crushed and humiliated people."

To raise these uncomfortable questions about U.S. foreign policy was difficult for many Americans, particularly in the aftermath of the attacks. Indeed, many were afraid to ask the right questions because they feared the answers. Still, I was convinced that it could not have been more important or timely.

Raising such questions was not popular, however. Detectives investigating a crime trying to establish a motive are generally not accused of defending the criminals. Fire inspectors inspecting the ruins of a building for the cause of the blaze are not accused of defending its destruction. Yet I found myself, along with scores of other Middle Eastern scholars, being attacked for supposedly defending terrorism.

Within a few months, I found out that a dossier about me--along with seven other professors specializing in the Middle East--had been compiled by Campus Watch, a project of the right-wing Middle East Forum, led by the Islamaphobic intellectual and occasional Bush administration adviser Daniel Pipes. The list of "anti-American" professors who had the audacity to raise concerns over certain U.S. policies also included some of the top scholars in the field, including John Esposito at Georgetown, Joel Beinin at Stanford, Ian Lustick at the University of Pennsylvania, Rashid Khalidi of the University of Chicago, and Edward Said at Columbia.

Various manifestations of this Campus Watch claim that I had said that 9/11 was "our fault" soon made its way to Fox News, MSNBC, radio talk shows throughout the nation and even into my short biographical entry in Wikipedia.

Soon thereafter, a number of my speaking invitations were rescinded. For example, I received a last-minute cancellation of my scheduled presentation on international law at the Arizona Bar Association's annual convention, which had been scheduled six months earlier, following the director and his board of governors being told I was "anti-American."

Others were altered. The provost of Hofstra University, where I was scheduled to give a plenary address on U.S. Middle East policy and international law at a peace studies conference, successfully demanded that the length of my presentation be substantially reduced and that organizers bring in a prominent neoconservative attorney and Breitbart contributor to follow me.

On Fox News, Sean Hannity claimed that Campus Watch was doing "American parents a favor" by citing "the extreme left-wing agenda like Mr. Zunes" so that parents, "when they're making decisions about whether or not to send their kids to Mr. Zunes' college like the University of San Francisco, they'll have at least some knowledge of where these people that will be educating their children are coming from."

Being tenured at a university with applications for admission steadily growing every year, I was not worried about the USF administration's response when the phone calls and emails from worried parents and alumni began pouring in in response to Hannity's statement. However, following the 9/11 attacks, Middle Eastern scholars in less secure situations had to think twice about publicly raising questions about U.S. policy in the region.

Perhaps more disturbingly, the attacks on Middle Eastern scholars were not limited to individuals who raised concerns over the Bush administration's policies, but the entire field of study. For example, Martin Kramer of the Washington Institute for Near East Policy argued in his book, Ivory Towers on Sand: The Failure of Middle Eastern Studies in America, that "The field is pervaded by hostility to American aims, interests, and power in the Middle East, and peopled by tenured radicals."

Regional specialists, given our unique understanding of parts of the world which few policymakers know firsthand, can play an invaluable role in the foreign policy sphere. Middle East scholars from across the ideological spectrum were almost uniformly opposed to a U.S. invasion of Iraq and other Bush administration policies post-9/11, because we had a good sense of the tragic consequences that would likely result. And yet, like Southeast Asia scholars 40 years earlier, who forewarned the tragedy that would unfold by a U.S. war in Vietnam, we were ridiculed and ignored and found our loyalty to our country questioned.

The United States, like other great powers, has made many tragic mistakes in its foreign policy, but never had the stakes been higher. Whatever crimes our government has committed in the past in Central America or Southeast Asia, no Nicaraguans or Vietnamese ever flew airplanes into buildings. By attacking the credibility of Middle East specialists who understood the dangerous ramifications of U.S. policy, it ended up being the right--not the left--which was endangering our national security.

Indeed, my decision to become a more public intellectual following the 9/11 tragedy was motivated by my understanding of how U.S. policy in the Middle East was putting all of us in danger, and by my desire to do my part to make America safer.

As the tragedies of Afghanistan and Iraq show, and as anti-Americanism in the Islamic world has only grown, the consequences of Americans unwilling to learn the lessons of 9/11 have become strikingly clear.

In the months leading up to the October 2002 vote authorizing the invasion of Iraq, I provided extensive material to a number of Congressional offices of prominent Democrats raising serious questions regarding the administration's claims that Saddam Hussein had somehow reconstituted his "weapons of mass destruction" and offensive delivery systems, or that he had operational ties to al-Qaeda. I also provided these offices and committee staff with what later proved to be rather prescient predictions of the disaster that would result from a U.S. invasion and occupation.

I later learned that a number of these offices failed to take my arguments seriously and successfully resisted requests that I be allowed to testify before relevant Congressional committees because they had heard I was "extreme" and "far left" in my views.

Other Middle East scholars had similar experiences. As chair of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, Joe Biden refused to allow hardly any of us to testify, instead stacking the witness list with supporters of the invasion who not only made the false claim that Iraq was amassing a large stockpile of "weapons of mass destruction," but insisted that U.S. occupation forces in Iraq would be "welcomed as liberators."

Had we been able to testify, we would have argued--among other things--that a U.S. invasion and occupation would encourage the rise of even larger and more extreme manifestations of Salafist extremism, as has indeed been manifested in the rises of the so-called Islamic State, an Iraqi-led group which was a direct consequence of that tragic war.

Attacks against scholars raising critical concerns in the post-9/11 era did not cause most of us to lose our jobs or stop us from speaking out. However, it did cause political leaders, journalists, and millions of ordinary citizens to not trust some of the country's most critical intellectual resources in formulating policies in subsequent decades.

As the tragedies of Afghanistan and Iraq show, and as anti-Americanism in the Islamic world has only grown, the consequences of Americans unwilling to learn the lessons of 9/11 have become strikingly clear.