The Government's 'Predictive Judgments' Land Innocent Travelers on the No Fly List Without Meaningful Redress

In the movie Minority Report, Hollywood depicts a future Washington, D.C., in which people are arrested by a special police force called Precrime, based on predictions that they will commit murders in the future. These predictions are not based on science, but on near-infallible psychics. Precrime asks for deference from judges, and gets it.

In the movie Minority Report, Hollywood depicts a future Washington, D.C., in which people are arrested by a special police force called Precrime, based on predictions that they will commit murders in the future. These predictions are not based on science, but on near-infallible psychics. Precrime asks for deference from judges, and gets it.

The U.S. government's reliance on "predictive judgments" to deprive Americans of their constitutionally protected liberties is no fiction. It's now central to the government's defense of its no-fly list.

The film's preventive policing model achieves a form of perfect safety, which is appealing: The number of murders goes down to zero, terrible tragedies are averted, and the federal government considers implementing Precrime nationwide. Until things go horribly wrong. Even in Hollywood, there are major issues with a crime prevention system that presumes future guilt without the ability to prove innocence.

The U.S. government's reliance on "predictive judgments" to deprive Americans of their constitutionally protected liberties is no fiction. It's now central to the government's defense of its no-fly list--a secretive watch list that bans people from flying to or from the United States or over American airspace--in a challenge brought by the American Civil Liberties Union.

Court filings show that the government is trying to predict whether people who have never been charged, let alone convicted, of any violent crime might nevertheless commit a violent terrorist act. Because the government predicts that our clients--all innocent U.S. citizens--might engage in violence at some unknown point in the future, it has grounded them indefinitely.

They are far from alone. Based on a leaked government document published by The Intercept last August, there were approximately 47,000 people on the no-fly list, of whom about 800 were U.S. citizens or legal permanent residents. In all likelihood, the numbers are higher now.

The government is trying to predict whether people who have never been charged with a violent crime will commit a terrorist act.

Worse, the U.S. government launched its predictive judgment model without offering any evidence whatsoever about its accuracy, any scientific basis or methodology that might justify it, or the extent to which it results in errors. In our case, we turned to two independent experts to evaluate the government's predictive method: Marc Sageman, a former longtime intelligence community professional and forensic psychologist with expertise in terrorism research, and James Austin, an expert in risk assessment in the criminal justice system. Neither found any indication that the government's predictive model even tries to use basic scientific methods to make and test its predictions. As Sageman says, despite years of research, no one inside or outside the government has devised a model that can predict with any reliability if a person will commit an act of terrorism.

When predictions of dangerousness are made and upheld in our courts, the government generally has to show that the particular individual has been charged with or convicted of a relevant prior crime. Even in that context, there are major concerns about the reliability and fairness of future threat assessments and their potential for arbitrary and discriminatory use. The same concerns exist in our case; our clients are all American Muslims. Applying basic scientific principles, our two experts found that the no-fly list's rate of error is extremely high, meaning that the government is blacklisting people who will never commit an act of terrorism.

It gets worse still.

Because the government's predictive model results in the blacklisting of people who are not terrorists, individuals on the no-fly list need a meaningful method of redress--a fair way to demonstrate their "innocence" of crimes they will never commit. The government refuses to provide these safeguards in its current so-called redress system, which violates the due process guarantees of the Constitution. It refuses to tell our clients all the reasons the government has for predicting future misconduct, leaving them to guess. It won't provide the evidence underlying those reasons, including government evidence that would undermine its predictions. And it refuses to provide a hearing for our clients to press their case to a neutral decision-maker and challenge government witnesses' hearsay or biases.

Without these basic requirements of a fair process, our clients can't meaningfully challenge the government's predictions. For example, the only reason the government provided to one of our clients is that he traveled to a particular country in a particular year. That's perfectly lawful conduct, no basis for predicting violence, and not enough information to challenge whatever other basis the government might have. In another case, the evidence the government is relying on--but not producing--includes information from FBI agents who unlawfully detained our client in East Africa for four months, abusing him and threatening him with torture and disappearance. The government also appears to be relying on electronic surveillance, without disclosing the legal basis for the surveillance or the results.

According to the government, national security requires this secrecy, even though Congress and the courts have devised time-tested tools used every day in national security and other cases to protect the government's secrets while providing individuals meaningful ways to challenge government deprivations of liberties. We have asked the court in our clients' case to strike down the government's current redress process as unconstitutional.

Otherwise, dystopian science fiction will become reality.

This piece originally appeared at Slate.

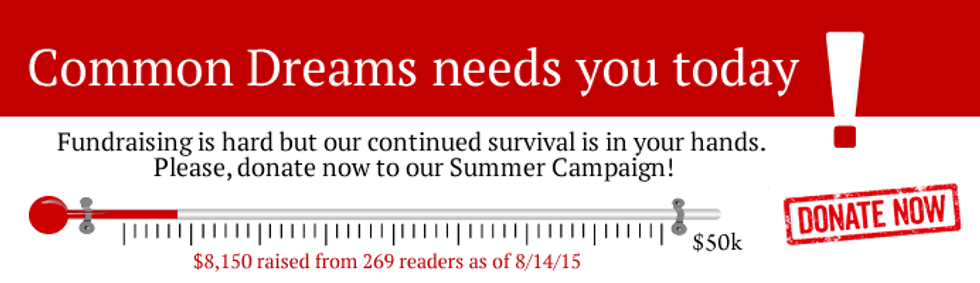

An Urgent Message From Our Co-Founder

Dear Common Dreams reader, The U.S. is on a fast track to authoritarianism like nothing I've ever seen. Meanwhile, corporate news outlets are utterly capitulating to Trump, twisting their coverage to avoid drawing his ire while lining up to stuff cash in his pockets. That's why I believe that Common Dreams is doing the best and most consequential reporting that we've ever done. Our small but mighty team is a progressive reporting powerhouse, covering the news every day that the corporate media never will. Our mission has always been simple: To inform. To inspire. And to ignite change for the common good. Now here's the key piece that I want all our readers to understand: None of this would be possible without your financial support. That's not just some fundraising cliche. It's the absolute and literal truth. We don't accept corporate advertising and never will. We don't have a paywall because we don't think people should be blocked from critical news based on their ability to pay. Everything we do is funded by the donations of readers like you. Will you donate now to help power the nonprofit, independent reporting of Common Dreams? Thank you for being a vital member of our community. Together, we can keep independent journalism alive when it’s needed most. - Craig Brown, Co-founder |

In the movie Minority Report, Hollywood depicts a future Washington, D.C., in which people are arrested by a special police force called Precrime, based on predictions that they will commit murders in the future. These predictions are not based on science, but on near-infallible psychics. Precrime asks for deference from judges, and gets it.

The U.S. government's reliance on "predictive judgments" to deprive Americans of their constitutionally protected liberties is no fiction. It's now central to the government's defense of its no-fly list.

The film's preventive policing model achieves a form of perfect safety, which is appealing: The number of murders goes down to zero, terrible tragedies are averted, and the federal government considers implementing Precrime nationwide. Until things go horribly wrong. Even in Hollywood, there are major issues with a crime prevention system that presumes future guilt without the ability to prove innocence.

The U.S. government's reliance on "predictive judgments" to deprive Americans of their constitutionally protected liberties is no fiction. It's now central to the government's defense of its no-fly list--a secretive watch list that bans people from flying to or from the United States or over American airspace--in a challenge brought by the American Civil Liberties Union.

Court filings show that the government is trying to predict whether people who have never been charged, let alone convicted, of any violent crime might nevertheless commit a violent terrorist act. Because the government predicts that our clients--all innocent U.S. citizens--might engage in violence at some unknown point in the future, it has grounded them indefinitely.

They are far from alone. Based on a leaked government document published by The Intercept last August, there were approximately 47,000 people on the no-fly list, of whom about 800 were U.S. citizens or legal permanent residents. In all likelihood, the numbers are higher now.

The government is trying to predict whether people who have never been charged with a violent crime will commit a terrorist act.

Worse, the U.S. government launched its predictive judgment model without offering any evidence whatsoever about its accuracy, any scientific basis or methodology that might justify it, or the extent to which it results in errors. In our case, we turned to two independent experts to evaluate the government's predictive method: Marc Sageman, a former longtime intelligence community professional and forensic psychologist with expertise in terrorism research, and James Austin, an expert in risk assessment in the criminal justice system. Neither found any indication that the government's predictive model even tries to use basic scientific methods to make and test its predictions. As Sageman says, despite years of research, no one inside or outside the government has devised a model that can predict with any reliability if a person will commit an act of terrorism.

When predictions of dangerousness are made and upheld in our courts, the government generally has to show that the particular individual has been charged with or convicted of a relevant prior crime. Even in that context, there are major concerns about the reliability and fairness of future threat assessments and their potential for arbitrary and discriminatory use. The same concerns exist in our case; our clients are all American Muslims. Applying basic scientific principles, our two experts found that the no-fly list's rate of error is extremely high, meaning that the government is blacklisting people who will never commit an act of terrorism.

It gets worse still.

Because the government's predictive model results in the blacklisting of people who are not terrorists, individuals on the no-fly list need a meaningful method of redress--a fair way to demonstrate their "innocence" of crimes they will never commit. The government refuses to provide these safeguards in its current so-called redress system, which violates the due process guarantees of the Constitution. It refuses to tell our clients all the reasons the government has for predicting future misconduct, leaving them to guess. It won't provide the evidence underlying those reasons, including government evidence that would undermine its predictions. And it refuses to provide a hearing for our clients to press their case to a neutral decision-maker and challenge government witnesses' hearsay or biases.

Without these basic requirements of a fair process, our clients can't meaningfully challenge the government's predictions. For example, the only reason the government provided to one of our clients is that he traveled to a particular country in a particular year. That's perfectly lawful conduct, no basis for predicting violence, and not enough information to challenge whatever other basis the government might have. In another case, the evidence the government is relying on--but not producing--includes information from FBI agents who unlawfully detained our client in East Africa for four months, abusing him and threatening him with torture and disappearance. The government also appears to be relying on electronic surveillance, without disclosing the legal basis for the surveillance or the results.

According to the government, national security requires this secrecy, even though Congress and the courts have devised time-tested tools used every day in national security and other cases to protect the government's secrets while providing individuals meaningful ways to challenge government deprivations of liberties. We have asked the court in our clients' case to strike down the government's current redress process as unconstitutional.

Otherwise, dystopian science fiction will become reality.

This piece originally appeared at Slate.

In the movie Minority Report, Hollywood depicts a future Washington, D.C., in which people are arrested by a special police force called Precrime, based on predictions that they will commit murders in the future. These predictions are not based on science, but on near-infallible psychics. Precrime asks for deference from judges, and gets it.

The U.S. government's reliance on "predictive judgments" to deprive Americans of their constitutionally protected liberties is no fiction. It's now central to the government's defense of its no-fly list.

The film's preventive policing model achieves a form of perfect safety, which is appealing: The number of murders goes down to zero, terrible tragedies are averted, and the federal government considers implementing Precrime nationwide. Until things go horribly wrong. Even in Hollywood, there are major issues with a crime prevention system that presumes future guilt without the ability to prove innocence.

The U.S. government's reliance on "predictive judgments" to deprive Americans of their constitutionally protected liberties is no fiction. It's now central to the government's defense of its no-fly list--a secretive watch list that bans people from flying to or from the United States or over American airspace--in a challenge brought by the American Civil Liberties Union.

Court filings show that the government is trying to predict whether people who have never been charged, let alone convicted, of any violent crime might nevertheless commit a violent terrorist act. Because the government predicts that our clients--all innocent U.S. citizens--might engage in violence at some unknown point in the future, it has grounded them indefinitely.

They are far from alone. Based on a leaked government document published by The Intercept last August, there were approximately 47,000 people on the no-fly list, of whom about 800 were U.S. citizens or legal permanent residents. In all likelihood, the numbers are higher now.

The government is trying to predict whether people who have never been charged with a violent crime will commit a terrorist act.

Worse, the U.S. government launched its predictive judgment model without offering any evidence whatsoever about its accuracy, any scientific basis or methodology that might justify it, or the extent to which it results in errors. In our case, we turned to two independent experts to evaluate the government's predictive method: Marc Sageman, a former longtime intelligence community professional and forensic psychologist with expertise in terrorism research, and James Austin, an expert in risk assessment in the criminal justice system. Neither found any indication that the government's predictive model even tries to use basic scientific methods to make and test its predictions. As Sageman says, despite years of research, no one inside or outside the government has devised a model that can predict with any reliability if a person will commit an act of terrorism.

When predictions of dangerousness are made and upheld in our courts, the government generally has to show that the particular individual has been charged with or convicted of a relevant prior crime. Even in that context, there are major concerns about the reliability and fairness of future threat assessments and their potential for arbitrary and discriminatory use. The same concerns exist in our case; our clients are all American Muslims. Applying basic scientific principles, our two experts found that the no-fly list's rate of error is extremely high, meaning that the government is blacklisting people who will never commit an act of terrorism.

It gets worse still.

Because the government's predictive model results in the blacklisting of people who are not terrorists, individuals on the no-fly list need a meaningful method of redress--a fair way to demonstrate their "innocence" of crimes they will never commit. The government refuses to provide these safeguards in its current so-called redress system, which violates the due process guarantees of the Constitution. It refuses to tell our clients all the reasons the government has for predicting future misconduct, leaving them to guess. It won't provide the evidence underlying those reasons, including government evidence that would undermine its predictions. And it refuses to provide a hearing for our clients to press their case to a neutral decision-maker and challenge government witnesses' hearsay or biases.

Without these basic requirements of a fair process, our clients can't meaningfully challenge the government's predictions. For example, the only reason the government provided to one of our clients is that he traveled to a particular country in a particular year. That's perfectly lawful conduct, no basis for predicting violence, and not enough information to challenge whatever other basis the government might have. In another case, the evidence the government is relying on--but not producing--includes information from FBI agents who unlawfully detained our client in East Africa for four months, abusing him and threatening him with torture and disappearance. The government also appears to be relying on electronic surveillance, without disclosing the legal basis for the surveillance or the results.

According to the government, national security requires this secrecy, even though Congress and the courts have devised time-tested tools used every day in national security and other cases to protect the government's secrets while providing individuals meaningful ways to challenge government deprivations of liberties. We have asked the court in our clients' case to strike down the government's current redress process as unconstitutional.

Otherwise, dystopian science fiction will become reality.

This piece originally appeared at Slate.