Oct 10, 2013

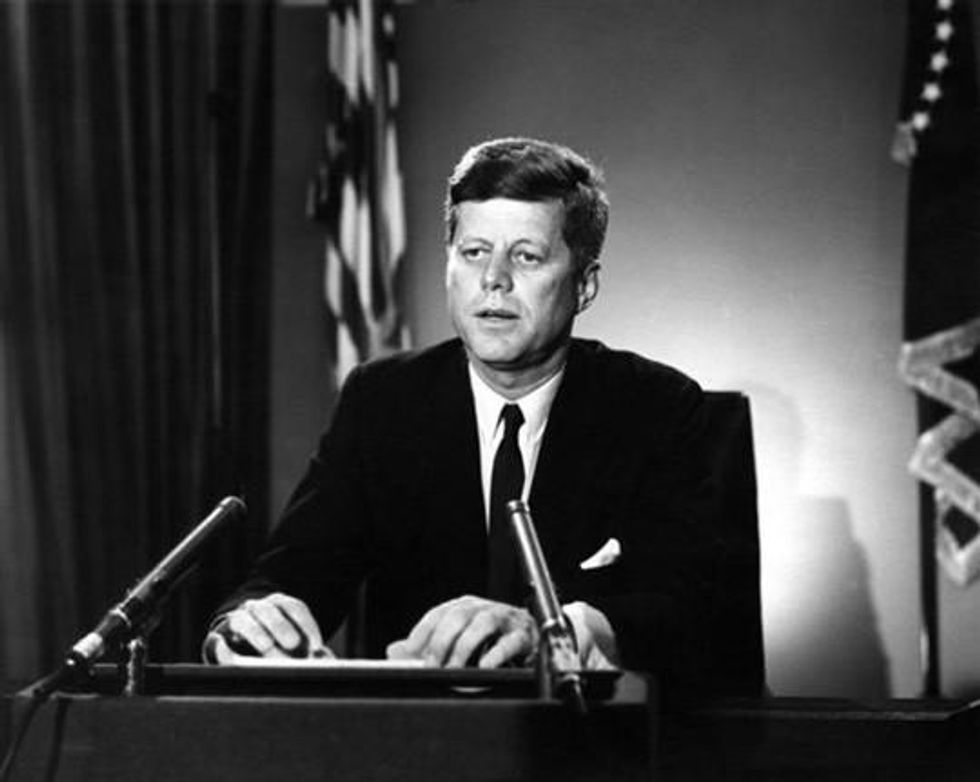

As we approach the 50th anniversary of President John F. Kennedy's assassination next month, we would do well to recall the extraordinary events of the last year of the president's life. Doing this not only provides context for a tragedy that took place in a very different world that our own; more significantly, it is an opportunity to ponder what James W. Douglass -- in his magisterial 2008 studyJFK and the Unspeakable -- persuasively argues are significant keys to understanding his death. Douglass's 12 years of research led him to conclude that the president was killed because he was beginning to shed the protective armor of the Cold Warrior -- at the height of the Cold War -- and decided, instead, to become a peacemaker.

In the bipolar geopolitics of the day, Kennedy's job description committed him to full-on conflict with the Soviet Union. The flash-points included Berlin, Vietnam and Cuba, and most dangerous of all was the accelerating nuclear arms race. How risky it was became clear with the Cuban Missile Crisis in October 1962, when the world came perilously close to a nuclear exchange that could have left hundreds of millions dead.

The seeds of Kennedy's unlikely move toward peace were sown during this potentially catastrophic incident. Successfully avoiding war in this situation not only meant making an accommodation with his counterpart, Premier Nikita Khrushchev; it meant staring down the forces within his own government, including the Joint Chiefs, that were clamoring for an all-out nuclear attack. This experience seems to have unleashed something in Kennedy. He felt his way toward challenging the ideological framework of his day, leading him to sometimes-secret efforts to make a dramatic shift in policy toward Cuba and the escalating war in Vietnam. Most of all, Kennedy launched a series of initiatives to end the nuclear threat, which, a few month before his death, resulted in the promulgation of the Limited Test Ban Treaty, an historic agreement that prohibited signatories -- including the Americans and the Russians -- from conducting nuclear tests in the atmosphere and under the oceans.

Fifty years ago today the Partial Test Ban Treaty went into effect. It was the fruit of steps Kennedy took, including his groundbreaking speech at American University earlier that year, which called for a shift in nuclear policy, including a unilateral moratorium in nuclear testing, proffered as an olive branch to the Soviet Union. That summer the barriers to success came down, with the United States and USSR initiating the pact in July.

The challenge facing Kennedy was Senate ratification, where there was strong opposition. In August, polling showed 80 percent of the public opposed the treaty. Deciding that "a near miracle was needed," Kennedy set out to change public opinion, initiating a public awareness campaign coordinated by peace activist Norman Cousins. In his book, Douglass writes, "The president told an August 7 meeting of key organizers that they were taking on a very tough job and had his total support." Referred to as the Citizens Committee, the group -- with representatives of many of the strongest peace organizations in the country as well as religious leaders, union representatives, some business executives, Nobel prize winners and scientists -- succeeded in reversing the public's attitude in a little over a month. Eighty percent of the country backed the plan, resulting in the Senate approving the treaty 80-19 -- 14 more votes than necessary.

This historic accomplishment -- which Kennedy, as Douglass details, hoped would be the beginning of the end of the Cold War -- was underscored by the fact that on the day the treaty went into effect, the Nobel Committee announced that Linus Pauling would receive that year's Peace Prize. In 1957, Pauling -- who had already won a Nobel Prize in chemistry -- drafted with two others the "Scientists' Bomb-Test Appeal" that garnered the signatures of 11,000 scientists and played a role in building the anti-testing movement.

While much of the rest of the world acclaimed the movement and its organizers, including Pauling, the Nobel laureate's activism was not warmly received by his own chemistry department at the California Institute of Technology, which refrained from formally congratulating him. (More significantly, Pauling's earlier activism against the bomb prompted the U.S. State Department to deny him a passport. It was only restored shortly before traveling to Oslo to pick up his first Nobel Prize in 1954.) Pauling continued to be active for peace the rest of his life. I had the chance to see him at a U.S. Nuclear Freeze Campaign gathering in the early 1980s.

Although it would be another quarter of a century before the global Comprehensive Test Ban Treaty would end below-ground nuclear tests, the partial test ban was an historic accomplishment, having far-reaching environmental and political consequences. There is also a treasure trove of lessons for us today, especially about the capacity we have to make headway on seemingly impossible challenges.

The "miracle" Kennedy was seeking was not so otherworldly after all. It began with his own risky steps toward a different world -- for which, Douglass's research convincingly suggests, he paid the ultimate price. Then there were the nitty-gritty mechanics of organizing below the surface of national policy. Even in the doldrums of August, organizers alerted, educated and mobilized the population to catalyze a shift in public opinion -- and, in turn, to generate support for peace in the Senate, which was mired in the paralyzing ideology of the Cold War.

There are many times when we are tempted to conclude that we do not have the ability to clamber out of the political quicksand in which we are so often stuck, in a world where we have traded the Cold War for a war on terror. Regimes of worldwide surveillance. Widening gaps in income. The climate crisis. The "us vs. them" world of the early 1960s has splintered into many hemorrhaging challenges.

Yet there is nothing magical or metaphysical about our paralysis -- or our liberation. It mostly requires a combination of gumption and plodding work from which the "miracle" of change can flow. This was true half a century ago, and it remains true today.

Why Your Ongoing Support Is Essential

Donald Trump’s attacks on democracy, justice, and a free press are escalating — putting everything we stand for at risk. We believe a better world is possible, but we can’t get there without your support. Common Dreams stands apart. We answer only to you — our readers, activists, and changemakers — not to billionaires or corporations. Our independence allows us to cover the vital stories that others won’t, spotlighting movements for peace, equality, and human rights. Right now, our work faces unprecedented challenges. Misinformation is spreading, journalists are under attack, and financial pressures are mounting. As a reader-supported, nonprofit newsroom, your support is crucial to keep this journalism alive. Whatever you can give — $10, $25, or $100 — helps us stay strong and responsive when the world needs us most. Together, we’ll continue to build the independent, courageous journalism our movement relies on. Thank you for being part of this community. |

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 License.

Ken Butigan

Ken Butigan is director of Pace e Bene, a nonprofit organization fostering nonviolent change through education, community and action. He also teaches peace studies at DePaul University and Loyola University in Chicago.

As we approach the 50th anniversary of President John F. Kennedy's assassination next month, we would do well to recall the extraordinary events of the last year of the president's life. Doing this not only provides context for a tragedy that took place in a very different world that our own; more significantly, it is an opportunity to ponder what James W. Douglass -- in his magisterial 2008 studyJFK and the Unspeakable -- persuasively argues are significant keys to understanding his death. Douglass's 12 years of research led him to conclude that the president was killed because he was beginning to shed the protective armor of the Cold Warrior -- at the height of the Cold War -- and decided, instead, to become a peacemaker.

In the bipolar geopolitics of the day, Kennedy's job description committed him to full-on conflict with the Soviet Union. The flash-points included Berlin, Vietnam and Cuba, and most dangerous of all was the accelerating nuclear arms race. How risky it was became clear with the Cuban Missile Crisis in October 1962, when the world came perilously close to a nuclear exchange that could have left hundreds of millions dead.

The seeds of Kennedy's unlikely move toward peace were sown during this potentially catastrophic incident. Successfully avoiding war in this situation not only meant making an accommodation with his counterpart, Premier Nikita Khrushchev; it meant staring down the forces within his own government, including the Joint Chiefs, that were clamoring for an all-out nuclear attack. This experience seems to have unleashed something in Kennedy. He felt his way toward challenging the ideological framework of his day, leading him to sometimes-secret efforts to make a dramatic shift in policy toward Cuba and the escalating war in Vietnam. Most of all, Kennedy launched a series of initiatives to end the nuclear threat, which, a few month before his death, resulted in the promulgation of the Limited Test Ban Treaty, an historic agreement that prohibited signatories -- including the Americans and the Russians -- from conducting nuclear tests in the atmosphere and under the oceans.

Fifty years ago today the Partial Test Ban Treaty went into effect. It was the fruit of steps Kennedy took, including his groundbreaking speech at American University earlier that year, which called for a shift in nuclear policy, including a unilateral moratorium in nuclear testing, proffered as an olive branch to the Soviet Union. That summer the barriers to success came down, with the United States and USSR initiating the pact in July.

The challenge facing Kennedy was Senate ratification, where there was strong opposition. In August, polling showed 80 percent of the public opposed the treaty. Deciding that "a near miracle was needed," Kennedy set out to change public opinion, initiating a public awareness campaign coordinated by peace activist Norman Cousins. In his book, Douglass writes, "The president told an August 7 meeting of key organizers that they were taking on a very tough job and had his total support." Referred to as the Citizens Committee, the group -- with representatives of many of the strongest peace organizations in the country as well as religious leaders, union representatives, some business executives, Nobel prize winners and scientists -- succeeded in reversing the public's attitude in a little over a month. Eighty percent of the country backed the plan, resulting in the Senate approving the treaty 80-19 -- 14 more votes than necessary.

This historic accomplishment -- which Kennedy, as Douglass details, hoped would be the beginning of the end of the Cold War -- was underscored by the fact that on the day the treaty went into effect, the Nobel Committee announced that Linus Pauling would receive that year's Peace Prize. In 1957, Pauling -- who had already won a Nobel Prize in chemistry -- drafted with two others the "Scientists' Bomb-Test Appeal" that garnered the signatures of 11,000 scientists and played a role in building the anti-testing movement.

While much of the rest of the world acclaimed the movement and its organizers, including Pauling, the Nobel laureate's activism was not warmly received by his own chemistry department at the California Institute of Technology, which refrained from formally congratulating him. (More significantly, Pauling's earlier activism against the bomb prompted the U.S. State Department to deny him a passport. It was only restored shortly before traveling to Oslo to pick up his first Nobel Prize in 1954.) Pauling continued to be active for peace the rest of his life. I had the chance to see him at a U.S. Nuclear Freeze Campaign gathering in the early 1980s.

Although it would be another quarter of a century before the global Comprehensive Test Ban Treaty would end below-ground nuclear tests, the partial test ban was an historic accomplishment, having far-reaching environmental and political consequences. There is also a treasure trove of lessons for us today, especially about the capacity we have to make headway on seemingly impossible challenges.

The "miracle" Kennedy was seeking was not so otherworldly after all. It began with his own risky steps toward a different world -- for which, Douglass's research convincingly suggests, he paid the ultimate price. Then there were the nitty-gritty mechanics of organizing below the surface of national policy. Even in the doldrums of August, organizers alerted, educated and mobilized the population to catalyze a shift in public opinion -- and, in turn, to generate support for peace in the Senate, which was mired in the paralyzing ideology of the Cold War.

There are many times when we are tempted to conclude that we do not have the ability to clamber out of the political quicksand in which we are so often stuck, in a world where we have traded the Cold War for a war on terror. Regimes of worldwide surveillance. Widening gaps in income. The climate crisis. The "us vs. them" world of the early 1960s has splintered into many hemorrhaging challenges.

Yet there is nothing magical or metaphysical about our paralysis -- or our liberation. It mostly requires a combination of gumption and plodding work from which the "miracle" of change can flow. This was true half a century ago, and it remains true today.

Ken Butigan

Ken Butigan is director of Pace e Bene, a nonprofit organization fostering nonviolent change through education, community and action. He also teaches peace studies at DePaul University and Loyola University in Chicago.

As we approach the 50th anniversary of President John F. Kennedy's assassination next month, we would do well to recall the extraordinary events of the last year of the president's life. Doing this not only provides context for a tragedy that took place in a very different world that our own; more significantly, it is an opportunity to ponder what James W. Douglass -- in his magisterial 2008 studyJFK and the Unspeakable -- persuasively argues are significant keys to understanding his death. Douglass's 12 years of research led him to conclude that the president was killed because he was beginning to shed the protective armor of the Cold Warrior -- at the height of the Cold War -- and decided, instead, to become a peacemaker.

In the bipolar geopolitics of the day, Kennedy's job description committed him to full-on conflict with the Soviet Union. The flash-points included Berlin, Vietnam and Cuba, and most dangerous of all was the accelerating nuclear arms race. How risky it was became clear with the Cuban Missile Crisis in October 1962, when the world came perilously close to a nuclear exchange that could have left hundreds of millions dead.

The seeds of Kennedy's unlikely move toward peace were sown during this potentially catastrophic incident. Successfully avoiding war in this situation not only meant making an accommodation with his counterpart, Premier Nikita Khrushchev; it meant staring down the forces within his own government, including the Joint Chiefs, that were clamoring for an all-out nuclear attack. This experience seems to have unleashed something in Kennedy. He felt his way toward challenging the ideological framework of his day, leading him to sometimes-secret efforts to make a dramatic shift in policy toward Cuba and the escalating war in Vietnam. Most of all, Kennedy launched a series of initiatives to end the nuclear threat, which, a few month before his death, resulted in the promulgation of the Limited Test Ban Treaty, an historic agreement that prohibited signatories -- including the Americans and the Russians -- from conducting nuclear tests in the atmosphere and under the oceans.

Fifty years ago today the Partial Test Ban Treaty went into effect. It was the fruit of steps Kennedy took, including his groundbreaking speech at American University earlier that year, which called for a shift in nuclear policy, including a unilateral moratorium in nuclear testing, proffered as an olive branch to the Soviet Union. That summer the barriers to success came down, with the United States and USSR initiating the pact in July.

The challenge facing Kennedy was Senate ratification, where there was strong opposition. In August, polling showed 80 percent of the public opposed the treaty. Deciding that "a near miracle was needed," Kennedy set out to change public opinion, initiating a public awareness campaign coordinated by peace activist Norman Cousins. In his book, Douglass writes, "The president told an August 7 meeting of key organizers that they were taking on a very tough job and had his total support." Referred to as the Citizens Committee, the group -- with representatives of many of the strongest peace organizations in the country as well as religious leaders, union representatives, some business executives, Nobel prize winners and scientists -- succeeded in reversing the public's attitude in a little over a month. Eighty percent of the country backed the plan, resulting in the Senate approving the treaty 80-19 -- 14 more votes than necessary.

This historic accomplishment -- which Kennedy, as Douglass details, hoped would be the beginning of the end of the Cold War -- was underscored by the fact that on the day the treaty went into effect, the Nobel Committee announced that Linus Pauling would receive that year's Peace Prize. In 1957, Pauling -- who had already won a Nobel Prize in chemistry -- drafted with two others the "Scientists' Bomb-Test Appeal" that garnered the signatures of 11,000 scientists and played a role in building the anti-testing movement.

While much of the rest of the world acclaimed the movement and its organizers, including Pauling, the Nobel laureate's activism was not warmly received by his own chemistry department at the California Institute of Technology, which refrained from formally congratulating him. (More significantly, Pauling's earlier activism against the bomb prompted the U.S. State Department to deny him a passport. It was only restored shortly before traveling to Oslo to pick up his first Nobel Prize in 1954.) Pauling continued to be active for peace the rest of his life. I had the chance to see him at a U.S. Nuclear Freeze Campaign gathering in the early 1980s.

Although it would be another quarter of a century before the global Comprehensive Test Ban Treaty would end below-ground nuclear tests, the partial test ban was an historic accomplishment, having far-reaching environmental and political consequences. There is also a treasure trove of lessons for us today, especially about the capacity we have to make headway on seemingly impossible challenges.

The "miracle" Kennedy was seeking was not so otherworldly after all. It began with his own risky steps toward a different world -- for which, Douglass's research convincingly suggests, he paid the ultimate price. Then there were the nitty-gritty mechanics of organizing below the surface of national policy. Even in the doldrums of August, organizers alerted, educated and mobilized the population to catalyze a shift in public opinion -- and, in turn, to generate support for peace in the Senate, which was mired in the paralyzing ideology of the Cold War.

There are many times when we are tempted to conclude that we do not have the ability to clamber out of the political quicksand in which we are so often stuck, in a world where we have traded the Cold War for a war on terror. Regimes of worldwide surveillance. Widening gaps in income. The climate crisis. The "us vs. them" world of the early 1960s has splintered into many hemorrhaging challenges.

Yet there is nothing magical or metaphysical about our paralysis -- or our liberation. It mostly requires a combination of gumption and plodding work from which the "miracle" of change can flow. This was true half a century ago, and it remains true today.

We've had enough. The 1% own and operate the corporate media. They are doing everything they can to defend the status quo, squash dissent and protect the wealthy and the powerful. The Common Dreams media model is different. We cover the news that matters to the 99%. Our mission? To inform. To inspire. To ignite change for the common good. How? Nonprofit. Independent. Reader-supported. Free to read. Free to republish. Free to share. With no advertising. No paywalls. No selling of your data. Thousands of small donations fund our newsroom and allow us to continue publishing. Can you chip in? We can't do it without you. Thank you.