SUBSCRIBE TO OUR FREE NEWSLETTER

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

5

#000000

#FFFFFF

To donate by check, phone, or other method, see our More Ways to Give page.

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

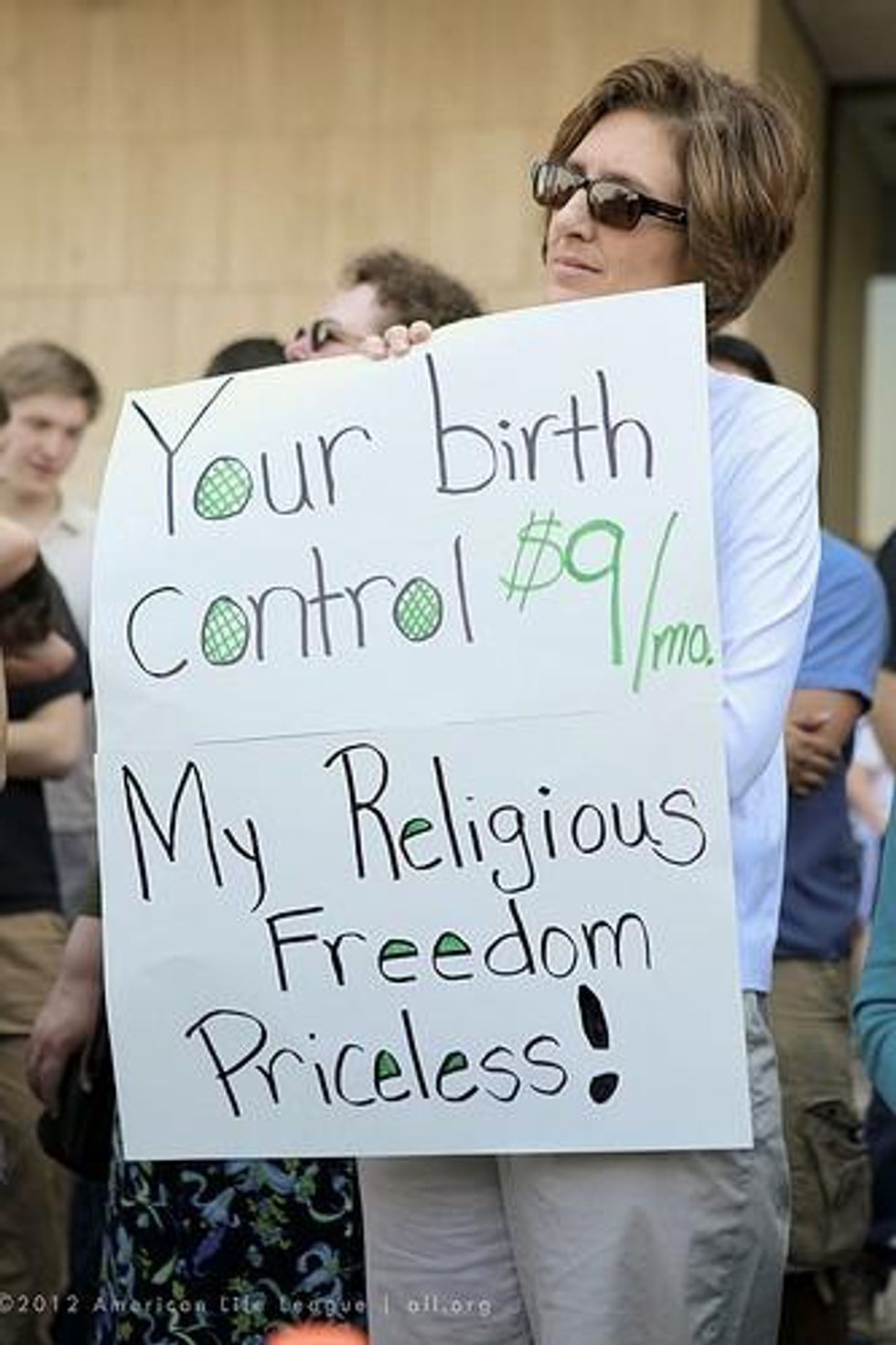

Freedom and liberty should be fairly simple: you don't step on my toes or impede my right to live according to my belief system, and I'll do the same. Unfortunately, reality is a bit more complicated than that, especially where religion is concerned. Increasingly, rightwing Christians aren't happy with being allowed to practice their own religion without interference; they want the right to mandate their beliefs across the board and call it "religious freedom".

The Obama administration came up with a compromise: houses of worship don't have to include contraceptive coverage in their employees' health plans. If there are other religious non-profits that object to contraception, they can be totally hands-off when it comes to birth control coverage; they won't have to pay for contraceptive coverage, nor will they have to contract or arrange for it. A third party will come in and formulate separate plans that cover contraception for employees at those institutions.

In other words, employees will have the right to affordable contraception if they want it, but employers that have a legitimate religious objection won't have to pay for it or otherwise take steps to obtain it to their employees. We're not talking about churches here; we're talking about religiously-affiliated non-profits, like hospitals, charities, social services groups and universities, which employ large numbers of people who don't share the religious beliefs of the owners.

So, the folks who oppose contraception don't have to pay for or use it, and the folks who are fine with it can see it treated like any other medication under their health plan. For-profit companies that happen to be owned by religious people don't qualify for the exemption. So, just because your boss has a particular view of a certain medication doesn't mean he gets to decide that the company's health plan won't cover it.

Sounds fair, right?

Not to the religious groups and individuals who not only want the right to practice their religious beliefs, but wish to force others to adhere to them, too. They oppose the compromise, arguing that any religious individual who owns a company should have the right to block medications that conflict with their beliefs from being covered in their employee health plan. The company suing over the law is a chain of craft stores called the Hobby Lobby, owned by conservative Christians who oppose hormonal contraception.

This is a for-profit business just like millions of others in America. Its owners aren't demanding their own rights to religious freedom; they're demanding the right to determine the healthcare their employees receive.

Taking the Hobby Lobby's argument to its logical conclusion, what if you're a plumber whose company happens to be owned by Jehovah's Witnesses: should your boss have the right to determine that your health insurance won't cover any surgeries or procedures that involve blood transfusions? What if you're a lawyer and the head of your firm is a Scientologist: should he be able to exclude coverage of psychiatric medication and treatment? What if you're a restaurant employee and the owner is a Muslim fundamentalist who opposes polio vaccines: should he have the right to refuse vaccination coverage? What if you're an administrator for a company owned by Christian Scientists: should they have the right to entirely refuse to cover their employees' healthcare?

The list goes on, because people hold all kinds of religious beliefs that, while their right and entitlement to hold, would be extremely burdensome and cruel if applied to everyone. There are religious followers who say their faith compels them to refuse or oppose chemotherapy, HIV treatment, vaccinations, fetal surgery, genetic counseling, prenatal diagnosis of disease and all sorts of other necessary components of any healthcare plan.

Personally refusing medical treatment is an important right. For example, if someone doesn't want to treat their cancer with radiation because it's against their religion, then refusing treatment is their prerogative. But I'd like my cancer treatment, please. And if my insurance comes from my employer, then it's simply not good enough to say, "You can be treated for cancer, you just have to pay for it yourself because we're going to intentionally select a plan that doesn't cover such treatments."

That's what the rightwing radicals are arguing about birth control: you can still use contraception; you just can't get it covered through your workplace health plan - into which you pay and for which you see a deduction from your wages.

The Hobby Lobby owners, by the way, claim that their religious rights are being violated because they "believe" that hormonal contraception and IUDs are abortifacients. The overwhelming weight of the scientific evidence indicates that's not actually true: contraception prevents pregnancy, it doesn't end it. But the scientific accuracy of the Hobby Lobby's claims wasn't an issue for the tenth circuit court of appeals (pdf), which held that the veracity of the belief doesn't matter as long as the holding of it is sincere.

That's a fair enough view generally, since most religious beliefs are by definition based in faith and not science. But it's different when religious individuals attempt to make a factual claim for their belief, as is happening here. The owners of the Hobby Lobby say that their religion compels them to oppose abortion, and that contraception causes abortion. The idea that contraception is an abortifacient is a relatively new one, unsupported by science and held by a minority of religious extremists. If an employer holds a counterfactual view about health or medicine - say, that HIV doesn't actually cause Aids and that pregnant HIV-positive women should not take antiretrovirals, which is the honestly-held but dangerously incorrect belief of many folks - do we really want to accept the view simply on the grounds that it's sincere, and thus allow the employer's opinions to dictate the care their employees can access?

For-profit companies also pay taxes, much of which goes to the US military, even if those businesses are owned and operated by individuals whose religious beliefs direct them to object to war and abstain from military duty. And for-profit businesses pay taxes which go into funding an electoral system, and those taxes are paid even by people whose religious beliefs compel them not to vote. Companies pay taxes that subsidize hog farmers, even if those companies are owned by Jews or Muslims who oppose the consumption of pork.

And for-profits also pay taxes that fund federal Title X programs, which pay for contraceptives.

A similar case cropped up 30 years ago, when a member of the Old Order Amish refused to withhold social security taxes from his employees or pay his employees' share of those taxes, because he believed that would violate the tenet of his faith requiring the Amish themselves to provide for the elderly. (Social security, the argument went, allowed other Amish to shirk their caretaking duties by allowing the state to step in.) The US supreme court held that "not all burdens on religion are unconstitutional", and that exempting religious people from paying taxes into anything they found objectionable would make the social security system, and the tax system generally, untenable.

In the contraception case, the tenth circuit court held differently. The healthcare mandate isn't a tax, but it is a large-scale government program, which would be rendered extremely difficult to administer if any for-profit company objected to covering this or that medication or treatment on the basis of religion. The tenth circuit, though, sided with the Hobby Lobby, holding that the company - which it deemed a "person" - had its religious freedom substantially burdened by the law, and that the government failed to adequately demonstrate a compelling interest in creating that burden.

That's the face of "religious freedom" today, according to the radical right: that is, not simply the freedom to practice your own religion, but the freedom to limit the rights and choices of anyone over whom you hold a modicum of power.

Healthcare is indeed a moral issue. So is contraception - access to it is a leading contributor to longer and healthier lives for women, better birth outcomes, lower abortion rates and healthier babies. Individuals who oppose birth control or any other medical treatment for reasons moral, religious or otherwise are welcome to hold that belief, act on it within their own skin and speak that belief freely without government interference.

But they should not be welcome to determine which medications their employees can access. Not if we want to maintain a balance of freedoms that allow all of us, no matter our religious beliefs or lack thereof, to live according to our most deeply-held values.

Dear Common Dreams reader, The U.S. is on a fast track to authoritarianism like nothing I've ever seen. Meanwhile, corporate news outlets are utterly capitulating to Trump, twisting their coverage to avoid drawing his ire while lining up to stuff cash in his pockets. That's why I believe that Common Dreams is doing the best and most consequential reporting that we've ever done. Our small but mighty team is a progressive reporting powerhouse, covering the news every day that the corporate media never will. Our mission has always been simple: To inform. To inspire. And to ignite change for the common good. Now here's the key piece that I want all our readers to understand: None of this would be possible without your financial support. That's not just some fundraising cliche. It's the absolute and literal truth. We don't accept corporate advertising and never will. We don't have a paywall because we don't think people should be blocked from critical news based on their ability to pay. Everything we do is funded by the donations of readers like you. Will you donate now to help power the nonprofit, independent reporting of Common Dreams? Thank you for being a vital member of our community. Together, we can keep independent journalism alive when it’s needed most. - Craig Brown, Co-founder |

Freedom and liberty should be fairly simple: you don't step on my toes or impede my right to live according to my belief system, and I'll do the same. Unfortunately, reality is a bit more complicated than that, especially where religion is concerned. Increasingly, rightwing Christians aren't happy with being allowed to practice their own religion without interference; they want the right to mandate their beliefs across the board and call it "religious freedom".

The Obama administration came up with a compromise: houses of worship don't have to include contraceptive coverage in their employees' health plans. If there are other religious non-profits that object to contraception, they can be totally hands-off when it comes to birth control coverage; they won't have to pay for contraceptive coverage, nor will they have to contract or arrange for it. A third party will come in and formulate separate plans that cover contraception for employees at those institutions.

In other words, employees will have the right to affordable contraception if they want it, but employers that have a legitimate religious objection won't have to pay for it or otherwise take steps to obtain it to their employees. We're not talking about churches here; we're talking about religiously-affiliated non-profits, like hospitals, charities, social services groups and universities, which employ large numbers of people who don't share the religious beliefs of the owners.

So, the folks who oppose contraception don't have to pay for or use it, and the folks who are fine with it can see it treated like any other medication under their health plan. For-profit companies that happen to be owned by religious people don't qualify for the exemption. So, just because your boss has a particular view of a certain medication doesn't mean he gets to decide that the company's health plan won't cover it.

Sounds fair, right?

Not to the religious groups and individuals who not only want the right to practice their religious beliefs, but wish to force others to adhere to them, too. They oppose the compromise, arguing that any religious individual who owns a company should have the right to block medications that conflict with their beliefs from being covered in their employee health plan. The company suing over the law is a chain of craft stores called the Hobby Lobby, owned by conservative Christians who oppose hormonal contraception.

This is a for-profit business just like millions of others in America. Its owners aren't demanding their own rights to religious freedom; they're demanding the right to determine the healthcare their employees receive.

Taking the Hobby Lobby's argument to its logical conclusion, what if you're a plumber whose company happens to be owned by Jehovah's Witnesses: should your boss have the right to determine that your health insurance won't cover any surgeries or procedures that involve blood transfusions? What if you're a lawyer and the head of your firm is a Scientologist: should he be able to exclude coverage of psychiatric medication and treatment? What if you're a restaurant employee and the owner is a Muslim fundamentalist who opposes polio vaccines: should he have the right to refuse vaccination coverage? What if you're an administrator for a company owned by Christian Scientists: should they have the right to entirely refuse to cover their employees' healthcare?

The list goes on, because people hold all kinds of religious beliefs that, while their right and entitlement to hold, would be extremely burdensome and cruel if applied to everyone. There are religious followers who say their faith compels them to refuse or oppose chemotherapy, HIV treatment, vaccinations, fetal surgery, genetic counseling, prenatal diagnosis of disease and all sorts of other necessary components of any healthcare plan.

Personally refusing medical treatment is an important right. For example, if someone doesn't want to treat their cancer with radiation because it's against their religion, then refusing treatment is their prerogative. But I'd like my cancer treatment, please. And if my insurance comes from my employer, then it's simply not good enough to say, "You can be treated for cancer, you just have to pay for it yourself because we're going to intentionally select a plan that doesn't cover such treatments."

That's what the rightwing radicals are arguing about birth control: you can still use contraception; you just can't get it covered through your workplace health plan - into which you pay and for which you see a deduction from your wages.

The Hobby Lobby owners, by the way, claim that their religious rights are being violated because they "believe" that hormonal contraception and IUDs are abortifacients. The overwhelming weight of the scientific evidence indicates that's not actually true: contraception prevents pregnancy, it doesn't end it. But the scientific accuracy of the Hobby Lobby's claims wasn't an issue for the tenth circuit court of appeals (pdf), which held that the veracity of the belief doesn't matter as long as the holding of it is sincere.

That's a fair enough view generally, since most religious beliefs are by definition based in faith and not science. But it's different when religious individuals attempt to make a factual claim for their belief, as is happening here. The owners of the Hobby Lobby say that their religion compels them to oppose abortion, and that contraception causes abortion. The idea that contraception is an abortifacient is a relatively new one, unsupported by science and held by a minority of religious extremists. If an employer holds a counterfactual view about health or medicine - say, that HIV doesn't actually cause Aids and that pregnant HIV-positive women should not take antiretrovirals, which is the honestly-held but dangerously incorrect belief of many folks - do we really want to accept the view simply on the grounds that it's sincere, and thus allow the employer's opinions to dictate the care their employees can access?

For-profit companies also pay taxes, much of which goes to the US military, even if those businesses are owned and operated by individuals whose religious beliefs direct them to object to war and abstain from military duty. And for-profit businesses pay taxes which go into funding an electoral system, and those taxes are paid even by people whose religious beliefs compel them not to vote. Companies pay taxes that subsidize hog farmers, even if those companies are owned by Jews or Muslims who oppose the consumption of pork.

And for-profits also pay taxes that fund federal Title X programs, which pay for contraceptives.

A similar case cropped up 30 years ago, when a member of the Old Order Amish refused to withhold social security taxes from his employees or pay his employees' share of those taxes, because he believed that would violate the tenet of his faith requiring the Amish themselves to provide for the elderly. (Social security, the argument went, allowed other Amish to shirk their caretaking duties by allowing the state to step in.) The US supreme court held that "not all burdens on religion are unconstitutional", and that exempting religious people from paying taxes into anything they found objectionable would make the social security system, and the tax system generally, untenable.

In the contraception case, the tenth circuit court held differently. The healthcare mandate isn't a tax, but it is a large-scale government program, which would be rendered extremely difficult to administer if any for-profit company objected to covering this or that medication or treatment on the basis of religion. The tenth circuit, though, sided with the Hobby Lobby, holding that the company - which it deemed a "person" - had its religious freedom substantially burdened by the law, and that the government failed to adequately demonstrate a compelling interest in creating that burden.

That's the face of "religious freedom" today, according to the radical right: that is, not simply the freedom to practice your own religion, but the freedom to limit the rights and choices of anyone over whom you hold a modicum of power.

Healthcare is indeed a moral issue. So is contraception - access to it is a leading contributor to longer and healthier lives for women, better birth outcomes, lower abortion rates and healthier babies. Individuals who oppose birth control or any other medical treatment for reasons moral, religious or otherwise are welcome to hold that belief, act on it within their own skin and speak that belief freely without government interference.

But they should not be welcome to determine which medications their employees can access. Not if we want to maintain a balance of freedoms that allow all of us, no matter our religious beliefs or lack thereof, to live according to our most deeply-held values.

Freedom and liberty should be fairly simple: you don't step on my toes or impede my right to live according to my belief system, and I'll do the same. Unfortunately, reality is a bit more complicated than that, especially where religion is concerned. Increasingly, rightwing Christians aren't happy with being allowed to practice their own religion without interference; they want the right to mandate their beliefs across the board and call it "religious freedom".

The Obama administration came up with a compromise: houses of worship don't have to include contraceptive coverage in their employees' health plans. If there are other religious non-profits that object to contraception, they can be totally hands-off when it comes to birth control coverage; they won't have to pay for contraceptive coverage, nor will they have to contract or arrange for it. A third party will come in and formulate separate plans that cover contraception for employees at those institutions.

In other words, employees will have the right to affordable contraception if they want it, but employers that have a legitimate religious objection won't have to pay for it or otherwise take steps to obtain it to their employees. We're not talking about churches here; we're talking about religiously-affiliated non-profits, like hospitals, charities, social services groups and universities, which employ large numbers of people who don't share the religious beliefs of the owners.

So, the folks who oppose contraception don't have to pay for or use it, and the folks who are fine with it can see it treated like any other medication under their health plan. For-profit companies that happen to be owned by religious people don't qualify for the exemption. So, just because your boss has a particular view of a certain medication doesn't mean he gets to decide that the company's health plan won't cover it.

Sounds fair, right?

Not to the religious groups and individuals who not only want the right to practice their religious beliefs, but wish to force others to adhere to them, too. They oppose the compromise, arguing that any religious individual who owns a company should have the right to block medications that conflict with their beliefs from being covered in their employee health plan. The company suing over the law is a chain of craft stores called the Hobby Lobby, owned by conservative Christians who oppose hormonal contraception.

This is a for-profit business just like millions of others in America. Its owners aren't demanding their own rights to religious freedom; they're demanding the right to determine the healthcare their employees receive.

Taking the Hobby Lobby's argument to its logical conclusion, what if you're a plumber whose company happens to be owned by Jehovah's Witnesses: should your boss have the right to determine that your health insurance won't cover any surgeries or procedures that involve blood transfusions? What if you're a lawyer and the head of your firm is a Scientologist: should he be able to exclude coverage of psychiatric medication and treatment? What if you're a restaurant employee and the owner is a Muslim fundamentalist who opposes polio vaccines: should he have the right to refuse vaccination coverage? What if you're an administrator for a company owned by Christian Scientists: should they have the right to entirely refuse to cover their employees' healthcare?

The list goes on, because people hold all kinds of religious beliefs that, while their right and entitlement to hold, would be extremely burdensome and cruel if applied to everyone. There are religious followers who say their faith compels them to refuse or oppose chemotherapy, HIV treatment, vaccinations, fetal surgery, genetic counseling, prenatal diagnosis of disease and all sorts of other necessary components of any healthcare plan.

Personally refusing medical treatment is an important right. For example, if someone doesn't want to treat their cancer with radiation because it's against their religion, then refusing treatment is their prerogative. But I'd like my cancer treatment, please. And if my insurance comes from my employer, then it's simply not good enough to say, "You can be treated for cancer, you just have to pay for it yourself because we're going to intentionally select a plan that doesn't cover such treatments."

That's what the rightwing radicals are arguing about birth control: you can still use contraception; you just can't get it covered through your workplace health plan - into which you pay and for which you see a deduction from your wages.

The Hobby Lobby owners, by the way, claim that their religious rights are being violated because they "believe" that hormonal contraception and IUDs are abortifacients. The overwhelming weight of the scientific evidence indicates that's not actually true: contraception prevents pregnancy, it doesn't end it. But the scientific accuracy of the Hobby Lobby's claims wasn't an issue for the tenth circuit court of appeals (pdf), which held that the veracity of the belief doesn't matter as long as the holding of it is sincere.

That's a fair enough view generally, since most religious beliefs are by definition based in faith and not science. But it's different when religious individuals attempt to make a factual claim for their belief, as is happening here. The owners of the Hobby Lobby say that their religion compels them to oppose abortion, and that contraception causes abortion. The idea that contraception is an abortifacient is a relatively new one, unsupported by science and held by a minority of religious extremists. If an employer holds a counterfactual view about health or medicine - say, that HIV doesn't actually cause Aids and that pregnant HIV-positive women should not take antiretrovirals, which is the honestly-held but dangerously incorrect belief of many folks - do we really want to accept the view simply on the grounds that it's sincere, and thus allow the employer's opinions to dictate the care their employees can access?

For-profit companies also pay taxes, much of which goes to the US military, even if those businesses are owned and operated by individuals whose religious beliefs direct them to object to war and abstain from military duty. And for-profit businesses pay taxes which go into funding an electoral system, and those taxes are paid even by people whose religious beliefs compel them not to vote. Companies pay taxes that subsidize hog farmers, even if those companies are owned by Jews or Muslims who oppose the consumption of pork.

And for-profits also pay taxes that fund federal Title X programs, which pay for contraceptives.

A similar case cropped up 30 years ago, when a member of the Old Order Amish refused to withhold social security taxes from his employees or pay his employees' share of those taxes, because he believed that would violate the tenet of his faith requiring the Amish themselves to provide for the elderly. (Social security, the argument went, allowed other Amish to shirk their caretaking duties by allowing the state to step in.) The US supreme court held that "not all burdens on religion are unconstitutional", and that exempting religious people from paying taxes into anything they found objectionable would make the social security system, and the tax system generally, untenable.

In the contraception case, the tenth circuit court held differently. The healthcare mandate isn't a tax, but it is a large-scale government program, which would be rendered extremely difficult to administer if any for-profit company objected to covering this or that medication or treatment on the basis of religion. The tenth circuit, though, sided with the Hobby Lobby, holding that the company - which it deemed a "person" - had its religious freedom substantially burdened by the law, and that the government failed to adequately demonstrate a compelling interest in creating that burden.

That's the face of "religious freedom" today, according to the radical right: that is, not simply the freedom to practice your own religion, but the freedom to limit the rights and choices of anyone over whom you hold a modicum of power.

Healthcare is indeed a moral issue. So is contraception - access to it is a leading contributor to longer and healthier lives for women, better birth outcomes, lower abortion rates and healthier babies. Individuals who oppose birth control or any other medical treatment for reasons moral, religious or otherwise are welcome to hold that belief, act on it within their own skin and speak that belief freely without government interference.

But they should not be welcome to determine which medications their employees can access. Not if we want to maintain a balance of freedoms that allow all of us, no matter our religious beliefs or lack thereof, to live according to our most deeply-held values.