SUBSCRIBE TO OUR FREE NEWSLETTER

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

5

#000000

#FFFFFF

To donate by check, phone, or other method, see our More Ways to Give page.

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

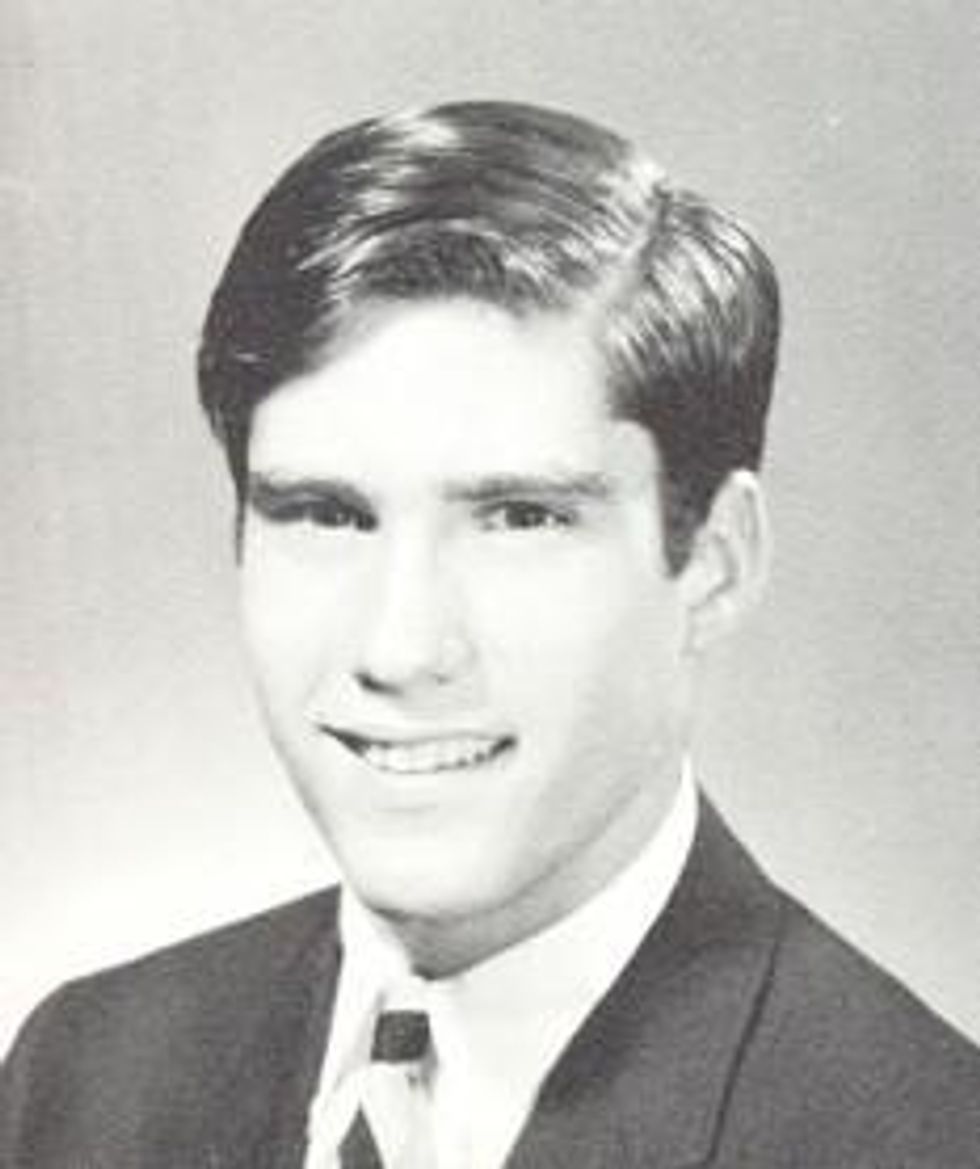

What is the defining image in the Washington Post's story on Mitt Romney, as a student at the Cranbrook School, bullying a gay teen-age boy? Maybe it's Romney, the eighteen-year-old son of a governor, spotting the student, John Lauber, with, as a classmate remembered, "bleached-blond hair that draped over one eye," and saying, "He can't look like that.

What is the defining image in the Washington Post's story on Mitt Romney, as a student at the Cranbrook School, bullying a gay teen-age boy? Maybe it's Romney, the eighteen-year-old son of a governor, spotting the student, John Lauber, with, as a classmate remembered, "bleached-blond hair that draped over one eye," and saying, "He can't look like that. That's wrong. Just look at him!" Or Romney, a few days later, "marching out of his own room ahead of a prep school posse shouting about their plan to cut Lauber's hair." Or the Post's description of the attack itself:

They came upon Lauber, tackled him and pinned him to the ground. As Lauber, his eyes filling with tears, screamed for help, Romney repeatedly clipped his hair with a pair of scissors.

It is hard to forget that scene after reading it; how easy could it be after living it? For the five former students who spoke to the Post's Jason Horowitz and Julie Tate--four of them allowing their names to be used--it seems to have impossible, becoming the sort of indelible, awful wrong that haunts both sides. "It happened very quickly, and to this day it troubles me," Thomas Buford said. "What a senseless, stupid, idiotic thing to do." "It was vicious," said Philip Maxwell. "He was just easy pickins," said Matthew Friedemann. He told the Post that he wondered if they'd get in trouble. They didn't; neither did Romney when another student thought to be gay spoke in class and he called out, "Atta Girl!" Lauber, however, was kicked out of Cranbrook, a private all-boys boarding and day school, when someone saw him smoking a cigarette, alone.

A fourth boy who was there that day, David Seed, still had it on his mind when he stopped for a drink at a bar in O'Hare Airport thirty years later, and "noticed a familiar face.":

"Hey, you're John Lauber," Seed recalled saying at the start of a brief conversation. Seed, also among those who witnessed the Romney-led incident, had gone on to a career as a teacher and principal. Now he had something to get off his chest.

"I'm sorry that I didn't do more to help in the situation," he said.

Lauber paused, then responded, "It was horrible." He went on to explain how frightened he was during the incident, and acknowledged to Seed, "It's something I have thought about a lot since then."

The one person who says he has not thought about it a lot is Mitt Romney. His campaign told the Post, "The stories of fifty years ago seem exaggerated and off base and Governor Romney has no memory of participating in these incidents." Thursday morning, as it became clear that this was no kind of answer--that the Post had this story down, with the accounts of the witnesses, who were members of both parties and had grown into a range of professions--Romney offered a blanket apology for anything that might have slipped his mind:

Back in high school, I did some dumb things, and if anybody was hurt by that or offended, obviously, I apologize for that... I participated in a lot of high jinks and pranks during high school, and some might have gone too far, and for that I apologize.

Does he count this as high jinks or a prank? It was neither; it is hard to imagine that hurt, rather than being the byproduct, was anything other than the point of the attack on Lauber. In terms of what a gay teen-ager might encounter, and what other boys might go along with at a school like Cranbrook, 1965 was different; but memory and empathy are not qualities that have only been invented since then. As our country has changed, and the other boys became men, they seem to have turned the events of that day over in their minds, not once, but many times, and made something new out of it. That it why it's all the worse that Romney says he can't remember--that he walked blithely away from the boy crying on the ground and kept going. Was there nowhere in him for that sight to lodge?

This story is resonant because one can, all too easily, see Romney walking away even now, or simply failing to connect, to grasp hurt.

What one does as a teen-ager does not need to mark a person or a politician for life. We can all be stupid. For Senator Rand Paul, it's Aqua Buddha; for Senator Robert Byrd, it was, more darkly and at a more mature age, his affiliation with the Ku Klux Klan. It took many more years than it should, but Byrd learned how to talk about that in a way that suggested understanding and repentance. Both of those are necessary.

And how far has Romney moved? This story is resonant because one can, all too easily, see Romney walking away even now, or simply failing to connect, to grasp hurt. How he talks about this incident will be impossible to divorce from how he talks about same-sex marriage in the wake of President Obama's announcement, and about questions of basic dignity for gay and lesbian Americans. But unless he deals with it soundly, it will also be present as people wonder about his compassion for anyone not as well situated and cosseted as he has always been. Who else might he walk away from? Until now, the campaign has talked about his fondness for pranks as a way to humanize him; his wife called him wild and crazy. Is this what they think that means?

Can Romney, in the end, see this story from anyone's perspective but his own? There were two vantage points on the campus of Cranbrook that day: Romney's, looking at Lauber; and that of Lauber, who was figuring out who he was, with his newly dyed hair "draped over his eye," or earlier, at a mirror, wondering how it looked. One hopes he decided it was beautiful, and never changed his mind. Lauber died, of cancer, in 2004, after a life that sounds peripatetic and, in some ways, unsettled. The Post spoke to his surviving sisters: "He kept his hair blond until he died, said his sister Chris. 'He never stopped bleaching it.' "

Dear Common Dreams reader, The U.S. is on a fast track to authoritarianism like nothing I've ever seen. Meanwhile, corporate news outlets are utterly capitulating to Trump, twisting their coverage to avoid drawing his ire while lining up to stuff cash in his pockets. That's why I believe that Common Dreams is doing the best and most consequential reporting that we've ever done. Our small but mighty team is a progressive reporting powerhouse, covering the news every day that the corporate media never will. Our mission has always been simple: To inform. To inspire. And to ignite change for the common good. Now here's the key piece that I want all our readers to understand: None of this would be possible without your financial support. That's not just some fundraising cliche. It's the absolute and literal truth. We don't accept corporate advertising and never will. We don't have a paywall because we don't think people should be blocked from critical news based on their ability to pay. Everything we do is funded by the donations of readers like you. Will you donate now to help power the nonprofit, independent reporting of Common Dreams? Thank you for being a vital member of our community. Together, we can keep independent journalism alive when it’s needed most. - Craig Brown, Co-founder |

What is the defining image in the Washington Post's story on Mitt Romney, as a student at the Cranbrook School, bullying a gay teen-age boy? Maybe it's Romney, the eighteen-year-old son of a governor, spotting the student, John Lauber, with, as a classmate remembered, "bleached-blond hair that draped over one eye," and saying, "He can't look like that. That's wrong. Just look at him!" Or Romney, a few days later, "marching out of his own room ahead of a prep school posse shouting about their plan to cut Lauber's hair." Or the Post's description of the attack itself:

They came upon Lauber, tackled him and pinned him to the ground. As Lauber, his eyes filling with tears, screamed for help, Romney repeatedly clipped his hair with a pair of scissors.

It is hard to forget that scene after reading it; how easy could it be after living it? For the five former students who spoke to the Post's Jason Horowitz and Julie Tate--four of them allowing their names to be used--it seems to have impossible, becoming the sort of indelible, awful wrong that haunts both sides. "It happened very quickly, and to this day it troubles me," Thomas Buford said. "What a senseless, stupid, idiotic thing to do." "It was vicious," said Philip Maxwell. "He was just easy pickins," said Matthew Friedemann. He told the Post that he wondered if they'd get in trouble. They didn't; neither did Romney when another student thought to be gay spoke in class and he called out, "Atta Girl!" Lauber, however, was kicked out of Cranbrook, a private all-boys boarding and day school, when someone saw him smoking a cigarette, alone.

A fourth boy who was there that day, David Seed, still had it on his mind when he stopped for a drink at a bar in O'Hare Airport thirty years later, and "noticed a familiar face.":

"Hey, you're John Lauber," Seed recalled saying at the start of a brief conversation. Seed, also among those who witnessed the Romney-led incident, had gone on to a career as a teacher and principal. Now he had something to get off his chest.

"I'm sorry that I didn't do more to help in the situation," he said.

Lauber paused, then responded, "It was horrible." He went on to explain how frightened he was during the incident, and acknowledged to Seed, "It's something I have thought about a lot since then."

The one person who says he has not thought about it a lot is Mitt Romney. His campaign told the Post, "The stories of fifty years ago seem exaggerated and off base and Governor Romney has no memory of participating in these incidents." Thursday morning, as it became clear that this was no kind of answer--that the Post had this story down, with the accounts of the witnesses, who were members of both parties and had grown into a range of professions--Romney offered a blanket apology for anything that might have slipped his mind:

Back in high school, I did some dumb things, and if anybody was hurt by that or offended, obviously, I apologize for that... I participated in a lot of high jinks and pranks during high school, and some might have gone too far, and for that I apologize.

Does he count this as high jinks or a prank? It was neither; it is hard to imagine that hurt, rather than being the byproduct, was anything other than the point of the attack on Lauber. In terms of what a gay teen-ager might encounter, and what other boys might go along with at a school like Cranbrook, 1965 was different; but memory and empathy are not qualities that have only been invented since then. As our country has changed, and the other boys became men, they seem to have turned the events of that day over in their minds, not once, but many times, and made something new out of it. That it why it's all the worse that Romney says he can't remember--that he walked blithely away from the boy crying on the ground and kept going. Was there nowhere in him for that sight to lodge?

This story is resonant because one can, all too easily, see Romney walking away even now, or simply failing to connect, to grasp hurt.

What one does as a teen-ager does not need to mark a person or a politician for life. We can all be stupid. For Senator Rand Paul, it's Aqua Buddha; for Senator Robert Byrd, it was, more darkly and at a more mature age, his affiliation with the Ku Klux Klan. It took many more years than it should, but Byrd learned how to talk about that in a way that suggested understanding and repentance. Both of those are necessary.

And how far has Romney moved? This story is resonant because one can, all too easily, see Romney walking away even now, or simply failing to connect, to grasp hurt. How he talks about this incident will be impossible to divorce from how he talks about same-sex marriage in the wake of President Obama's announcement, and about questions of basic dignity for gay and lesbian Americans. But unless he deals with it soundly, it will also be present as people wonder about his compassion for anyone not as well situated and cosseted as he has always been. Who else might he walk away from? Until now, the campaign has talked about his fondness for pranks as a way to humanize him; his wife called him wild and crazy. Is this what they think that means?

Can Romney, in the end, see this story from anyone's perspective but his own? There were two vantage points on the campus of Cranbrook that day: Romney's, looking at Lauber; and that of Lauber, who was figuring out who he was, with his newly dyed hair "draped over his eye," or earlier, at a mirror, wondering how it looked. One hopes he decided it was beautiful, and never changed his mind. Lauber died, of cancer, in 2004, after a life that sounds peripatetic and, in some ways, unsettled. The Post spoke to his surviving sisters: "He kept his hair blond until he died, said his sister Chris. 'He never stopped bleaching it.' "

What is the defining image in the Washington Post's story on Mitt Romney, as a student at the Cranbrook School, bullying a gay teen-age boy? Maybe it's Romney, the eighteen-year-old son of a governor, spotting the student, John Lauber, with, as a classmate remembered, "bleached-blond hair that draped over one eye," and saying, "He can't look like that. That's wrong. Just look at him!" Or Romney, a few days later, "marching out of his own room ahead of a prep school posse shouting about their plan to cut Lauber's hair." Or the Post's description of the attack itself:

They came upon Lauber, tackled him and pinned him to the ground. As Lauber, his eyes filling with tears, screamed for help, Romney repeatedly clipped his hair with a pair of scissors.

It is hard to forget that scene after reading it; how easy could it be after living it? For the five former students who spoke to the Post's Jason Horowitz and Julie Tate--four of them allowing their names to be used--it seems to have impossible, becoming the sort of indelible, awful wrong that haunts both sides. "It happened very quickly, and to this day it troubles me," Thomas Buford said. "What a senseless, stupid, idiotic thing to do." "It was vicious," said Philip Maxwell. "He was just easy pickins," said Matthew Friedemann. He told the Post that he wondered if they'd get in trouble. They didn't; neither did Romney when another student thought to be gay spoke in class and he called out, "Atta Girl!" Lauber, however, was kicked out of Cranbrook, a private all-boys boarding and day school, when someone saw him smoking a cigarette, alone.

A fourth boy who was there that day, David Seed, still had it on his mind when he stopped for a drink at a bar in O'Hare Airport thirty years later, and "noticed a familiar face.":

"Hey, you're John Lauber," Seed recalled saying at the start of a brief conversation. Seed, also among those who witnessed the Romney-led incident, had gone on to a career as a teacher and principal. Now he had something to get off his chest.

"I'm sorry that I didn't do more to help in the situation," he said.

Lauber paused, then responded, "It was horrible." He went on to explain how frightened he was during the incident, and acknowledged to Seed, "It's something I have thought about a lot since then."

The one person who says he has not thought about it a lot is Mitt Romney. His campaign told the Post, "The stories of fifty years ago seem exaggerated and off base and Governor Romney has no memory of participating in these incidents." Thursday morning, as it became clear that this was no kind of answer--that the Post had this story down, with the accounts of the witnesses, who were members of both parties and had grown into a range of professions--Romney offered a blanket apology for anything that might have slipped his mind:

Back in high school, I did some dumb things, and if anybody was hurt by that or offended, obviously, I apologize for that... I participated in a lot of high jinks and pranks during high school, and some might have gone too far, and for that I apologize.

Does he count this as high jinks or a prank? It was neither; it is hard to imagine that hurt, rather than being the byproduct, was anything other than the point of the attack on Lauber. In terms of what a gay teen-ager might encounter, and what other boys might go along with at a school like Cranbrook, 1965 was different; but memory and empathy are not qualities that have only been invented since then. As our country has changed, and the other boys became men, they seem to have turned the events of that day over in their minds, not once, but many times, and made something new out of it. That it why it's all the worse that Romney says he can't remember--that he walked blithely away from the boy crying on the ground and kept going. Was there nowhere in him for that sight to lodge?

This story is resonant because one can, all too easily, see Romney walking away even now, or simply failing to connect, to grasp hurt.

What one does as a teen-ager does not need to mark a person or a politician for life. We can all be stupid. For Senator Rand Paul, it's Aqua Buddha; for Senator Robert Byrd, it was, more darkly and at a more mature age, his affiliation with the Ku Klux Klan. It took many more years than it should, but Byrd learned how to talk about that in a way that suggested understanding and repentance. Both of those are necessary.

And how far has Romney moved? This story is resonant because one can, all too easily, see Romney walking away even now, or simply failing to connect, to grasp hurt. How he talks about this incident will be impossible to divorce from how he talks about same-sex marriage in the wake of President Obama's announcement, and about questions of basic dignity for gay and lesbian Americans. But unless he deals with it soundly, it will also be present as people wonder about his compassion for anyone not as well situated and cosseted as he has always been. Who else might he walk away from? Until now, the campaign has talked about his fondness for pranks as a way to humanize him; his wife called him wild and crazy. Is this what they think that means?

Can Romney, in the end, see this story from anyone's perspective but his own? There were two vantage points on the campus of Cranbrook that day: Romney's, looking at Lauber; and that of Lauber, who was figuring out who he was, with his newly dyed hair "draped over his eye," or earlier, at a mirror, wondering how it looked. One hopes he decided it was beautiful, and never changed his mind. Lauber died, of cancer, in 2004, after a life that sounds peripatetic and, in some ways, unsettled. The Post spoke to his surviving sisters: "He kept his hair blond until he died, said his sister Chris. 'He never stopped bleaching it.' "