SUBSCRIBE TO OUR FREE NEWSLETTER

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

5

#000000

#FFFFFF

To donate by check, phone, or other method, see our More Ways to Give page.

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

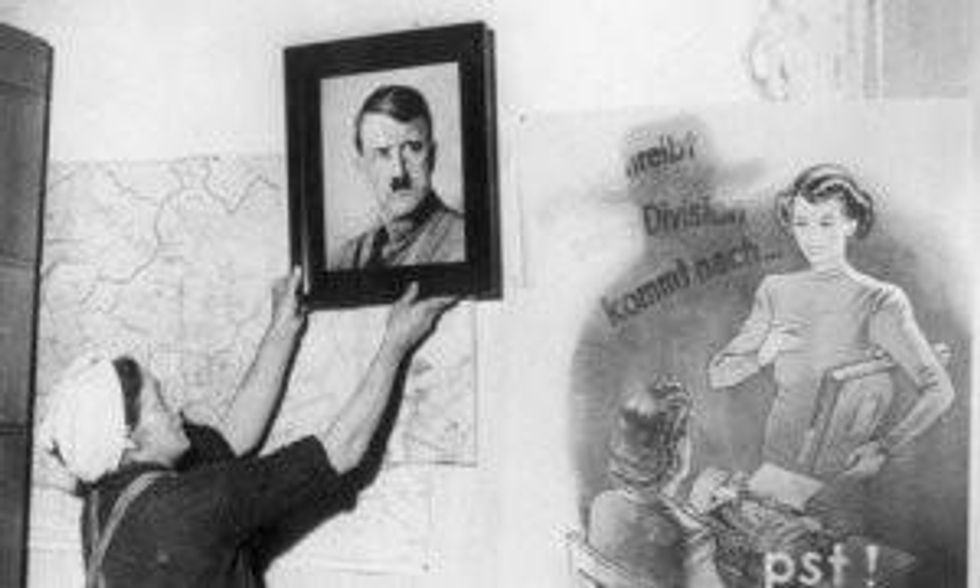

Digging into the rubble of bombed-out Frankfurt-am-Main after the second world war, I stumbled on two human skeletons who were among the last living survivors of the Hitler regime's anti-Nazi political parties. They were old, semi-starving men, working deliberately apart from each other in the corpse-smelling basement of a ruined apartment house, each of them kept alive by a fierce will to revive what had been, respectively, the Weimar Republic's mass socialist (SPD) and communist (KPD) movements. Catastrophically, their parties had refused to unite against Hitler, and both men had spent the Nazi years in Sachsenhausen concentration camp.

I had to speak separately to each man, in my broken "Blitz German", because despite all they had suffered, they still would not speak to each other, blaming the other's organisation for pre-war errors and betrayals. It was amazing to me, as a fresh-faced young GI, how old quarrels could be kept venomous for so long, at such a human cost.

Afterwards, as a spectator at the Nuremberg war crimes trial, locking eyes with Hitler's henchman Herman Goring in a staring contest (he won), I wondered: if you don't want the worst, maybe you had better learn to work with the least worst.

That's "coalition politics", the vehicle I was raised in during the era of Franklin and Eleanor Roosevelt. What remains today of the New Deal's welfare state - a total good, for me and my family - was rammed through by a Democratic party (with plenty of Republican sympathisers) composed of crooked big-city bosses, southern racists, small-town bigots, rightwing Catholics, blacks, Jews, progressives of all types, enlightened (or scared) capitalists and so on.

Saul Alinsky, America's most effective and successful neighbourhood organiser, called it "harmony of dissonance". In my Chicago, he organised the squalid slum known as Back of the (Stock)Yards, which was, in his words, "a cesspool of hate; the Poles, Slovaks, Germans, Negroes, Mexicans and Lithuanians all hated each other and all of them hated the Irish, who returned the sentiment in spades". The same for the black ghetto of Woodlawn. Short of outright fascists, there was nobody he wouldn't try to rope into his schemes to repair a neighborhood.

Alinsky's first principle was: you appeal to people's self-interest not their altruism. His second and final principle: holier-than-thou rigid dogma is a loser.

In winning some of our past struggles - civil rights, gay rights, women's rights, disabled people's rights - along the way, somehow we've forgotten this more hard-nosed, yet generous way of thinking about people who disagree with us. Professional blowhards like Rick Perry, Palin and Bachmann are beyond redemption, since it's in their self-interest to be cruel and delusional. And, yes, of course, there are plenty of ordinary people with a permanent Ku Klux Klan tattooed on their hearts.

But not everybody who opposes abortion, or is prejudiced against gays, or is suspicious of immigrants and wary of "big government", is obnoxious and untalkable to. After all, many of us have such Disagreeables in our own families. So what? You stop talking to them?

When did we lose patience and decide everyone in the Tea Party movement was evil, racist and stupid?

Nobody is unorganisable. For example, recently, I've been in touch with a lot of Ron Paul supporters around the country, from Maine to Oregon, and found them not all of a sameness. Most seem to be as fed up as we are with the Obama/Bush wars, and disgusted by federal wiretaps, surveillance and entrapments. Like Joe Stiglitz, the Nobel economics laureate, they also understand the close link between the $5tn wars and a job-bleeding America. Such areas of agreement can be explored, negotiated, argued about.

A coalition of vastly different opinions is not a love-marriage. But it's an alliance of sorts to work together, if possible, on a national repair job. It's the exact opposite of Obama pleading "Can't we all get along?" to the Republican and Blue Dog Democrat barbarians scaling the walls and itching to cut our throats.

The Wisconsin recall experience has taught us lessons. One of which is that no matter how hard you work - and my gosh, the Midwest unions and progressives went all out! - there are still lots of voters out there who simply don't like what we stand for. Yet.

Unlike pre-war Weimar Germany, there is no massive fracturing of the American left - mainly because there's hardly anything there to fracture. We're inert. The organising "space" may be not so much in rallying our own troops once again "unto the breach, dear friends", but among the ranks of the anti-imperialist right, which has been around, in one form or another, for 150 years.

The German Widerstand, the anti-Hitler resistance, never got its act together, despite individual acts of heroism. Maybe things were so bad, and Hitler so popular and so ruthless, that nothing would have helped. But they could have tried to work together.

Dear Common Dreams reader, The U.S. is on a fast track to authoritarianism like nothing I've ever seen. Meanwhile, corporate news outlets are utterly capitulating to Trump, twisting their coverage to avoid drawing his ire while lining up to stuff cash in his pockets. That's why I believe that Common Dreams is doing the best and most consequential reporting that we've ever done. Our small but mighty team is a progressive reporting powerhouse, covering the news every day that the corporate media never will. Our mission has always been simple: To inform. To inspire. And to ignite change for the common good. Now here's the key piece that I want all our readers to understand: None of this would be possible without your financial support. That's not just some fundraising cliche. It's the absolute and literal truth. We don't accept corporate advertising and never will. We don't have a paywall because we don't think people should be blocked from critical news based on their ability to pay. Everything we do is funded by the donations of readers like you. Will you donate now to help power the nonprofit, independent reporting of Common Dreams? Thank you for being a vital member of our community. Together, we can keep independent journalism alive when it’s needed most. - Craig Brown, Co-founder |

Digging into the rubble of bombed-out Frankfurt-am-Main after the second world war, I stumbled on two human skeletons who were among the last living survivors of the Hitler regime's anti-Nazi political parties. They were old, semi-starving men, working deliberately apart from each other in the corpse-smelling basement of a ruined apartment house, each of them kept alive by a fierce will to revive what had been, respectively, the Weimar Republic's mass socialist (SPD) and communist (KPD) movements. Catastrophically, their parties had refused to unite against Hitler, and both men had spent the Nazi years in Sachsenhausen concentration camp.

I had to speak separately to each man, in my broken "Blitz German", because despite all they had suffered, they still would not speak to each other, blaming the other's organisation for pre-war errors and betrayals. It was amazing to me, as a fresh-faced young GI, how old quarrels could be kept venomous for so long, at such a human cost.

Afterwards, as a spectator at the Nuremberg war crimes trial, locking eyes with Hitler's henchman Herman Goring in a staring contest (he won), I wondered: if you don't want the worst, maybe you had better learn to work with the least worst.

That's "coalition politics", the vehicle I was raised in during the era of Franklin and Eleanor Roosevelt. What remains today of the New Deal's welfare state - a total good, for me and my family - was rammed through by a Democratic party (with plenty of Republican sympathisers) composed of crooked big-city bosses, southern racists, small-town bigots, rightwing Catholics, blacks, Jews, progressives of all types, enlightened (or scared) capitalists and so on.

Saul Alinsky, America's most effective and successful neighbourhood organiser, called it "harmony of dissonance". In my Chicago, he organised the squalid slum known as Back of the (Stock)Yards, which was, in his words, "a cesspool of hate; the Poles, Slovaks, Germans, Negroes, Mexicans and Lithuanians all hated each other and all of them hated the Irish, who returned the sentiment in spades". The same for the black ghetto of Woodlawn. Short of outright fascists, there was nobody he wouldn't try to rope into his schemes to repair a neighborhood.

Alinsky's first principle was: you appeal to people's self-interest not their altruism. His second and final principle: holier-than-thou rigid dogma is a loser.

In winning some of our past struggles - civil rights, gay rights, women's rights, disabled people's rights - along the way, somehow we've forgotten this more hard-nosed, yet generous way of thinking about people who disagree with us. Professional blowhards like Rick Perry, Palin and Bachmann are beyond redemption, since it's in their self-interest to be cruel and delusional. And, yes, of course, there are plenty of ordinary people with a permanent Ku Klux Klan tattooed on their hearts.

But not everybody who opposes abortion, or is prejudiced against gays, or is suspicious of immigrants and wary of "big government", is obnoxious and untalkable to. After all, many of us have such Disagreeables in our own families. So what? You stop talking to them?

When did we lose patience and decide everyone in the Tea Party movement was evil, racist and stupid?

Nobody is unorganisable. For example, recently, I've been in touch with a lot of Ron Paul supporters around the country, from Maine to Oregon, and found them not all of a sameness. Most seem to be as fed up as we are with the Obama/Bush wars, and disgusted by federal wiretaps, surveillance and entrapments. Like Joe Stiglitz, the Nobel economics laureate, they also understand the close link between the $5tn wars and a job-bleeding America. Such areas of agreement can be explored, negotiated, argued about.

A coalition of vastly different opinions is not a love-marriage. But it's an alliance of sorts to work together, if possible, on a national repair job. It's the exact opposite of Obama pleading "Can't we all get along?" to the Republican and Blue Dog Democrat barbarians scaling the walls and itching to cut our throats.

The Wisconsin recall experience has taught us lessons. One of which is that no matter how hard you work - and my gosh, the Midwest unions and progressives went all out! - there are still lots of voters out there who simply don't like what we stand for. Yet.

Unlike pre-war Weimar Germany, there is no massive fracturing of the American left - mainly because there's hardly anything there to fracture. We're inert. The organising "space" may be not so much in rallying our own troops once again "unto the breach, dear friends", but among the ranks of the anti-imperialist right, which has been around, in one form or another, for 150 years.

The German Widerstand, the anti-Hitler resistance, never got its act together, despite individual acts of heroism. Maybe things were so bad, and Hitler so popular and so ruthless, that nothing would have helped. But they could have tried to work together.

Digging into the rubble of bombed-out Frankfurt-am-Main after the second world war, I stumbled on two human skeletons who were among the last living survivors of the Hitler regime's anti-Nazi political parties. They were old, semi-starving men, working deliberately apart from each other in the corpse-smelling basement of a ruined apartment house, each of them kept alive by a fierce will to revive what had been, respectively, the Weimar Republic's mass socialist (SPD) and communist (KPD) movements. Catastrophically, their parties had refused to unite against Hitler, and both men had spent the Nazi years in Sachsenhausen concentration camp.

I had to speak separately to each man, in my broken "Blitz German", because despite all they had suffered, they still would not speak to each other, blaming the other's organisation for pre-war errors and betrayals. It was amazing to me, as a fresh-faced young GI, how old quarrels could be kept venomous for so long, at such a human cost.

Afterwards, as a spectator at the Nuremberg war crimes trial, locking eyes with Hitler's henchman Herman Goring in a staring contest (he won), I wondered: if you don't want the worst, maybe you had better learn to work with the least worst.

That's "coalition politics", the vehicle I was raised in during the era of Franklin and Eleanor Roosevelt. What remains today of the New Deal's welfare state - a total good, for me and my family - was rammed through by a Democratic party (with plenty of Republican sympathisers) composed of crooked big-city bosses, southern racists, small-town bigots, rightwing Catholics, blacks, Jews, progressives of all types, enlightened (or scared) capitalists and so on.

Saul Alinsky, America's most effective and successful neighbourhood organiser, called it "harmony of dissonance". In my Chicago, he organised the squalid slum known as Back of the (Stock)Yards, which was, in his words, "a cesspool of hate; the Poles, Slovaks, Germans, Negroes, Mexicans and Lithuanians all hated each other and all of them hated the Irish, who returned the sentiment in spades". The same for the black ghetto of Woodlawn. Short of outright fascists, there was nobody he wouldn't try to rope into his schemes to repair a neighborhood.

Alinsky's first principle was: you appeal to people's self-interest not their altruism. His second and final principle: holier-than-thou rigid dogma is a loser.

In winning some of our past struggles - civil rights, gay rights, women's rights, disabled people's rights - along the way, somehow we've forgotten this more hard-nosed, yet generous way of thinking about people who disagree with us. Professional blowhards like Rick Perry, Palin and Bachmann are beyond redemption, since it's in their self-interest to be cruel and delusional. And, yes, of course, there are plenty of ordinary people with a permanent Ku Klux Klan tattooed on their hearts.

But not everybody who opposes abortion, or is prejudiced against gays, or is suspicious of immigrants and wary of "big government", is obnoxious and untalkable to. After all, many of us have such Disagreeables in our own families. So what? You stop talking to them?

When did we lose patience and decide everyone in the Tea Party movement was evil, racist and stupid?

Nobody is unorganisable. For example, recently, I've been in touch with a lot of Ron Paul supporters around the country, from Maine to Oregon, and found them not all of a sameness. Most seem to be as fed up as we are with the Obama/Bush wars, and disgusted by federal wiretaps, surveillance and entrapments. Like Joe Stiglitz, the Nobel economics laureate, they also understand the close link between the $5tn wars and a job-bleeding America. Such areas of agreement can be explored, negotiated, argued about.

A coalition of vastly different opinions is not a love-marriage. But it's an alliance of sorts to work together, if possible, on a national repair job. It's the exact opposite of Obama pleading "Can't we all get along?" to the Republican and Blue Dog Democrat barbarians scaling the walls and itching to cut our throats.

The Wisconsin recall experience has taught us lessons. One of which is that no matter how hard you work - and my gosh, the Midwest unions and progressives went all out! - there are still lots of voters out there who simply don't like what we stand for. Yet.

Unlike pre-war Weimar Germany, there is no massive fracturing of the American left - mainly because there's hardly anything there to fracture. We're inert. The organising "space" may be not so much in rallying our own troops once again "unto the breach, dear friends", but among the ranks of the anti-imperialist right, which has been around, in one form or another, for 150 years.

The German Widerstand, the anti-Hitler resistance, never got its act together, despite individual acts of heroism. Maybe things were so bad, and Hitler so popular and so ruthless, that nothing would have helped. But they could have tried to work together.