Copenhagen Negotiators Bicker and Filibuster While the Biosphere Burns

George Monbiot despairs at the chaotic, disastrous denouement of a chaotic and disastrous climate summit

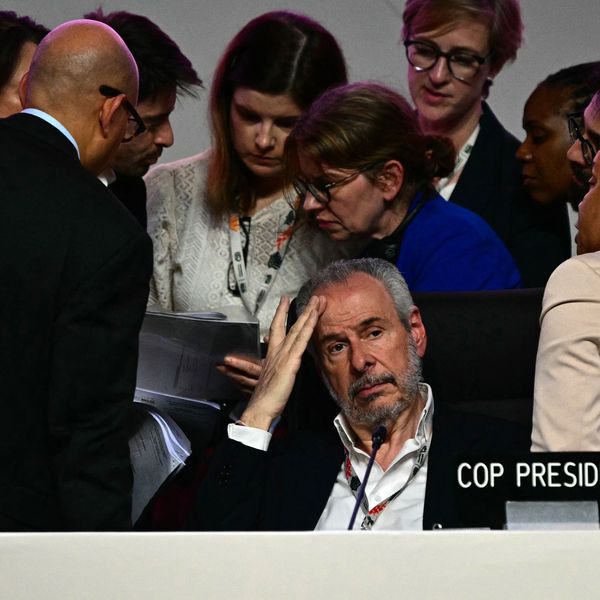

First they put the planet in square brackets, now they have deleted it from the text. At the end it was no longer about saving the biosphere: it was just a matter of saving face. As the talks melted down, everything that might have made a new treaty worthwhile was scratched out. Any deal would do, as long as the negotiators could pretend they have achieved something. A clearer and less destructive treaty than the text that emerged would be a sheaf of blank paper, which every negotiating party solemnly sits down to sign.

This was the chaotic, disastrous denouement of a chaotic and disastrous summit. The event has been attended by historic levels of incompetence. Delegates arriving from the tropics spent 10 hours queueing in sub-zero temperatures without shelter, food or drink, let alone any explanation or announcement, before being turned away. Some people fainted from exposure; it's surprising that no one died. The process of negotiation was just as obtuse: there was no evidence here of the innovative methods of dispute resolution developed recently by mediators and coaches, just the same old pig-headed wrestling.

Watching this stupid summit via webcam (I wasn't allowed in either), it struck me that the treaty-making system has scarcely changed in 130 years. There's a wider range of faces, fewer handlebar moustaches, frock coats or pickelhaubes, but otherwise, when the world's governments try to decide how to carve up the atmosphere, they might have been attending the conference of Berlin in 1884. It's as if democratisation and the flowering of civil society, advocacy and self-determination had never happened. Governments, whether elected or not, without reference to their own citizens let alone those of other nations, assert their right to draw lines across the global commons and decide who gets what. This is a scramble for the atmosphere comparable in style and intent to the scramble for Africa.

At no point has the injustice at the heart of multilateralism been addressed or even acknowledged: the interests of states and the interests of the world's people are not the same. Often they are diametrically opposed. In this case, most rich and rapidly developing states have sought through these talks to seize as great a chunk of the atmosphere for themselves as they can - to grab bigger rights to pollute than their competitors. The process couldn't have been better designed to produce the wrong results.

I spent most of my time at the Klimaforum, the alternative conference set up by just four paid staff, which 50,000 people attended without a hitch. (I know which team I would put in charge of saving the planet.) There the barrister Polly Higgins laid out a different approach. Her declaration of planetary rights invests ecosystems with similar legal safeguards to those won by humans after the second world war. It changes the legal relationship between humans, the atmosphere and the biosphere from ownership to stewardship. It creates a global framework for negotiation which gives nation states less discretion to dispose of ecosystems and the people who depend on them.

Even before the farce in Copenhagen began it was looking like it might be too late to prevent two or more degrees of global warming. The nation states, pursuing their own interests, have each been passing the parcel of responsibility since they decided to take action in 1992. We have now lost 17 precious years, possibly the only years in which climate breakdown could have been prevented. This has not happened by accident: it is the result of a systematic campaign of sabotage by certain states, driven and promoted by the energy industries. This idiocy has been aided and abetted by the nations characterised, until now, as the good guys: those that have made firm commitments, only to invalidate them with loopholes, false accounting and outsourcing. In all cases immediate self-interest has trumped the long-term welfare of humankind. Corporate profits and political expediency have proved more urgent considerations than either the natural world or human civilisation. Our political systems are incapable of discharging the main function of government: to protect us from each other.

Goodbye Africa, goodbye south Asia; goodbye glaciers and sea ice, coral reefs and rainforest. It was nice knowing you. Not that we really cared. The governments which moved so swiftly to save the banks have bickered and filibustered while the biosphere burns.

An Urgent Message From Our Co-Founder

Dear Common Dreams reader, The U.S. is on a fast track to authoritarianism like nothing I've ever seen. Meanwhile, corporate news outlets are utterly capitulating to Trump, twisting their coverage to avoid drawing his ire while lining up to stuff cash in his pockets. That's why I believe that Common Dreams is doing the best and most consequential reporting that we've ever done. Our small but mighty team is a progressive reporting powerhouse, covering the news every day that the corporate media never will. Our mission has always been simple: To inform. To inspire. And to ignite change for the common good. Now here's the key piece that I want all our readers to understand: None of this would be possible without your financial support. That's not just some fundraising cliche. It's the absolute and literal truth. We don't accept corporate advertising and never will. We don't have a paywall because we don't think people should be blocked from critical news based on their ability to pay. Everything we do is funded by the donations of readers like you. Will you donate now to help power the nonprofit, independent reporting of Common Dreams? Thank you for being a vital member of our community. Together, we can keep independent journalism alive when it’s needed most. - Craig Brown, Co-founder |

First they put the planet in square brackets, now they have deleted it from the text. At the end it was no longer about saving the biosphere: it was just a matter of saving face. As the talks melted down, everything that might have made a new treaty worthwhile was scratched out. Any deal would do, as long as the negotiators could pretend they have achieved something. A clearer and less destructive treaty than the text that emerged would be a sheaf of blank paper, which every negotiating party solemnly sits down to sign.

This was the chaotic, disastrous denouement of a chaotic and disastrous summit. The event has been attended by historic levels of incompetence. Delegates arriving from the tropics spent 10 hours queueing in sub-zero temperatures without shelter, food or drink, let alone any explanation or announcement, before being turned away. Some people fainted from exposure; it's surprising that no one died. The process of negotiation was just as obtuse: there was no evidence here of the innovative methods of dispute resolution developed recently by mediators and coaches, just the same old pig-headed wrestling.

Watching this stupid summit via webcam (I wasn't allowed in either), it struck me that the treaty-making system has scarcely changed in 130 years. There's a wider range of faces, fewer handlebar moustaches, frock coats or pickelhaubes, but otherwise, when the world's governments try to decide how to carve up the atmosphere, they might have been attending the conference of Berlin in 1884. It's as if democratisation and the flowering of civil society, advocacy and self-determination had never happened. Governments, whether elected or not, without reference to their own citizens let alone those of other nations, assert their right to draw lines across the global commons and decide who gets what. This is a scramble for the atmosphere comparable in style and intent to the scramble for Africa.

At no point has the injustice at the heart of multilateralism been addressed or even acknowledged: the interests of states and the interests of the world's people are not the same. Often they are diametrically opposed. In this case, most rich and rapidly developing states have sought through these talks to seize as great a chunk of the atmosphere for themselves as they can - to grab bigger rights to pollute than their competitors. The process couldn't have been better designed to produce the wrong results.

I spent most of my time at the Klimaforum, the alternative conference set up by just four paid staff, which 50,000 people attended without a hitch. (I know which team I would put in charge of saving the planet.) There the barrister Polly Higgins laid out a different approach. Her declaration of planetary rights invests ecosystems with similar legal safeguards to those won by humans after the second world war. It changes the legal relationship between humans, the atmosphere and the biosphere from ownership to stewardship. It creates a global framework for negotiation which gives nation states less discretion to dispose of ecosystems and the people who depend on them.

Even before the farce in Copenhagen began it was looking like it might be too late to prevent two or more degrees of global warming. The nation states, pursuing their own interests, have each been passing the parcel of responsibility since they decided to take action in 1992. We have now lost 17 precious years, possibly the only years in which climate breakdown could have been prevented. This has not happened by accident: it is the result of a systematic campaign of sabotage by certain states, driven and promoted by the energy industries. This idiocy has been aided and abetted by the nations characterised, until now, as the good guys: those that have made firm commitments, only to invalidate them with loopholes, false accounting and outsourcing. In all cases immediate self-interest has trumped the long-term welfare of humankind. Corporate profits and political expediency have proved more urgent considerations than either the natural world or human civilisation. Our political systems are incapable of discharging the main function of government: to protect us from each other.

Goodbye Africa, goodbye south Asia; goodbye glaciers and sea ice, coral reefs and rainforest. It was nice knowing you. Not that we really cared. The governments which moved so swiftly to save the banks have bickered and filibustered while the biosphere burns.

First they put the planet in square brackets, now they have deleted it from the text. At the end it was no longer about saving the biosphere: it was just a matter of saving face. As the talks melted down, everything that might have made a new treaty worthwhile was scratched out. Any deal would do, as long as the negotiators could pretend they have achieved something. A clearer and less destructive treaty than the text that emerged would be a sheaf of blank paper, which every negotiating party solemnly sits down to sign.

This was the chaotic, disastrous denouement of a chaotic and disastrous summit. The event has been attended by historic levels of incompetence. Delegates arriving from the tropics spent 10 hours queueing in sub-zero temperatures without shelter, food or drink, let alone any explanation or announcement, before being turned away. Some people fainted from exposure; it's surprising that no one died. The process of negotiation was just as obtuse: there was no evidence here of the innovative methods of dispute resolution developed recently by mediators and coaches, just the same old pig-headed wrestling.

Watching this stupid summit via webcam (I wasn't allowed in either), it struck me that the treaty-making system has scarcely changed in 130 years. There's a wider range of faces, fewer handlebar moustaches, frock coats or pickelhaubes, but otherwise, when the world's governments try to decide how to carve up the atmosphere, they might have been attending the conference of Berlin in 1884. It's as if democratisation and the flowering of civil society, advocacy and self-determination had never happened. Governments, whether elected or not, without reference to their own citizens let alone those of other nations, assert their right to draw lines across the global commons and decide who gets what. This is a scramble for the atmosphere comparable in style and intent to the scramble for Africa.

At no point has the injustice at the heart of multilateralism been addressed or even acknowledged: the interests of states and the interests of the world's people are not the same. Often they are diametrically opposed. In this case, most rich and rapidly developing states have sought through these talks to seize as great a chunk of the atmosphere for themselves as they can - to grab bigger rights to pollute than their competitors. The process couldn't have been better designed to produce the wrong results.

I spent most of my time at the Klimaforum, the alternative conference set up by just four paid staff, which 50,000 people attended without a hitch. (I know which team I would put in charge of saving the planet.) There the barrister Polly Higgins laid out a different approach. Her declaration of planetary rights invests ecosystems with similar legal safeguards to those won by humans after the second world war. It changes the legal relationship between humans, the atmosphere and the biosphere from ownership to stewardship. It creates a global framework for negotiation which gives nation states less discretion to dispose of ecosystems and the people who depend on them.

Even before the farce in Copenhagen began it was looking like it might be too late to prevent two or more degrees of global warming. The nation states, pursuing their own interests, have each been passing the parcel of responsibility since they decided to take action in 1992. We have now lost 17 precious years, possibly the only years in which climate breakdown could have been prevented. This has not happened by accident: it is the result of a systematic campaign of sabotage by certain states, driven and promoted by the energy industries. This idiocy has been aided and abetted by the nations characterised, until now, as the good guys: those that have made firm commitments, only to invalidate them with loopholes, false accounting and outsourcing. In all cases immediate self-interest has trumped the long-term welfare of humankind. Corporate profits and political expediency have proved more urgent considerations than either the natural world or human civilisation. Our political systems are incapable of discharging the main function of government: to protect us from each other.

Goodbye Africa, goodbye south Asia; goodbye glaciers and sea ice, coral reefs and rainforest. It was nice knowing you. Not that we really cared. The governments which moved so swiftly to save the banks have bickered and filibustered while the biosphere burns.