How Forever Chemicals 'Poisoned the World'

A new book tells the history of how U.S. corporations sold the country on toxic chemicals, while lying about the harm they posed.

Every child is born pre-polluted—polluted with dangerous, human-made chemicals.

So writes Mariah Blake in the preface to her important book, They Poisoned the World: Life and Death in the Age of Forever Chemicals. The United States is the place where she writes that every child is born pre-polluted, but I think merely because she's writing about the United States, not because it isn't also true of everywhere else on Earth. In fact, Blake quotes Rachel Carson as having written in 1962 that every human everywhere is subjected to dangerous chemicals from the moment of conception.

But U.S. corporations—chiefly Dupont and 3M—are the source of the problem. Well, them and the U.S. government or lack thereof. Forever chemicals, like standing armies, carpet bombings, nuclear weapons, income taxes, and so many of the things we hold dear, come from World War II, upon the end of which, as Blake notes, poison gases became pesticides, explosives became fertilizers, and military plastics became consumer goods. It's just possible that the respectable consumerism kicked off in the 1950s was a lot more reckless and damaging than any 1960s counterculture.

The origins of plastics—and of forever chemicals—goes back to research by DuPont prior to and during WWII. And the government's coverup of the dangers was part of the Manhattan Project—as was the public-relations campaign around the benefits of fluoride. The original sites that proximity to which could put cancer-causing forever chemicals into your body were Manhattan Project sites, and the Atomic Energy Commission covered up the dangers at the time, as did corporate profiteers, which have run denial and misinformation campaigns ever since. Before the first no-stick frying pan landed on the first shelf of the first U.S. store, Dupont was strategizing to minimize its financial risk for the harm and suffering expected to result. The tobacco and fossil fuel liars learned from the plastics liars, but were not as good at it.

I applaud Mariah Blake for telling moving, personal stories, and framing them in the broadest context.

Two big players drove the demand for fluorochemicals in the 1960s and 70s, as the dangers became more widely known, Blake writes. One was the U.S. Navy, which worked with 3M to develop PFOA-containing fire-fighting foam that Blake writes would be deployed at military bases across the country. (More accurate would be across the world.) The other was a former DuPont engineer named Bill Gore who had worked on military uses of Teflon but would go on to create Gore-Tex.

Blake's book does a tremendous job shaped around the familiar outline of interspersing particular personal stories with broader history. Her primary focus is on individuals in Hoosick Falls, New York, who become victims and activists, though stories from Parkersburg, West Virginia (perhaps known from the film Dark Waters) and North Bennington, Vermont, and elsewhere are also included. The corporate poisoners in Hoosick include Honeywell, which some readers will be aware is a major weapons maker. These stories are crushingly tragic with far too much detail to be statistics. But the statistics are also in the book. In 2016, over 5 million people in 19 U.S. states and several U.S. territories were informed their drinking water had unsafe levels of chemicals. I can hardly begin to imagine reading each of their stories, stories of death, suffering, birth defects, mothers giving birth in U.S. hospitals—like mothers near U.S. bases in Iraq—expecting birth defects; stories of choices being made between job security and challenging the poisoning of water by corporations that had known what would happen before they did it and had done it anyway.

Also chronicled here is the history of military and corporate control of environmental regulation, if it even merited that name prior to the sprees of deregulation indulged in since the era of the Teflon President Ronald Reagan (may his nickname evolve to mean deadly poisoner rather than impunity). Blake takes the history back to my neighbor enslaver Thomas Jefferson who gave DuPont government contracts for gunpowder long before Dupont's WWI merchandising of death, or (not mentioned in the book) its funding of fascist groups in the U.S., or its investment in both sides of WWII including GM's production of Nazi trucks and IG Farben's production of poison gas for concentration camps. The "regulation" history includes the Dupont-led establishment of the principle that all new chemicals are safe until proven otherwise. This, Blake notes, is why the vast majority of over 80,000 chemicals circulating in the United States (and presumably indifferent to borders) have never been tested for safety by the U.S. government.

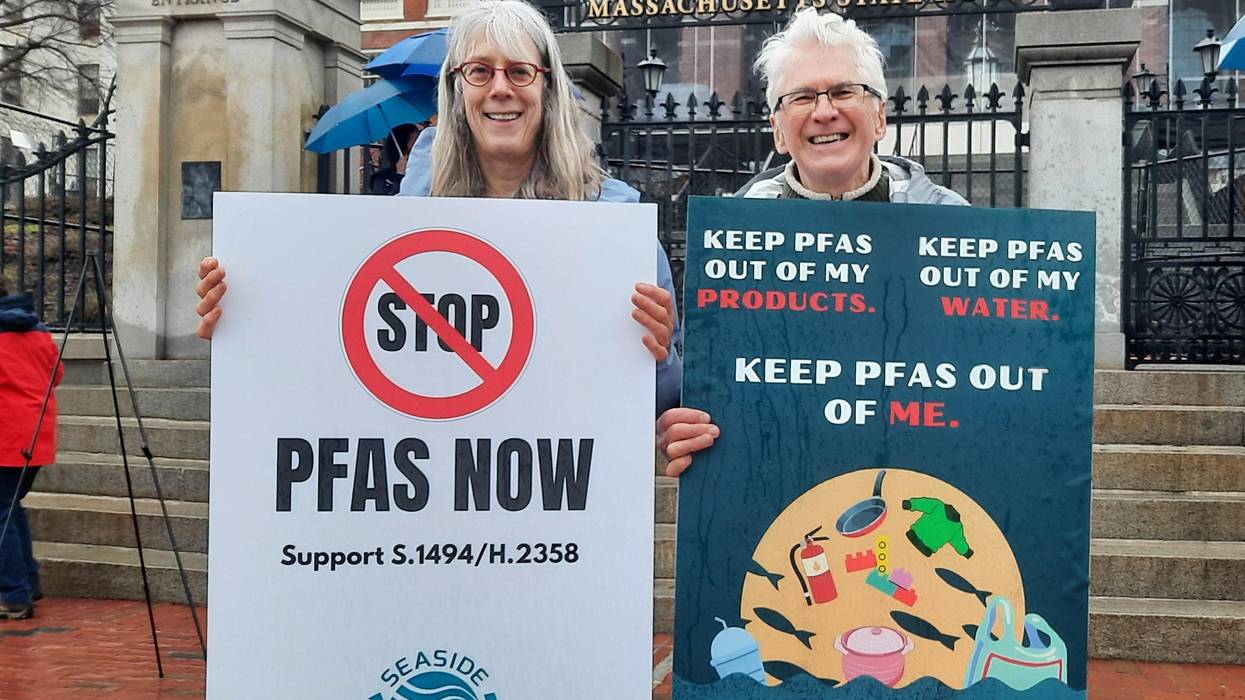

Forever chemicals come from ground water, smokestacks, landfills, wastewater treatment plants, sewage sludge spread on farmland, firefighting foam, poisoned fish eaten by humans, and all variety of consumer goods. The particular ones that are subject to countless lawsuits are being replaced by new ones, less known and possibly more dangerous, but legal by virtue of not having been made illegal. They saturate the world before anyone begins studying them. Congress changed the absurd legal practice of approving all new chemicals in 2016, just in time for Trump 1.0 to illegally change it back.

I applaud Mariah Blake for telling moving, personal stories, and framing them in the broadest context. I quibble with a single sentence in the book, the one claiming that the bombing of Nagasaki "ended the war" which is a falsehood marketed by some of the very same people who told the world forever chemicals were good for us.