SUBSCRIBE TO OUR FREE NEWSLETTER

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

5

#000000

#FFFFFF

To donate by check, phone, or other method, see our More Ways to Give page.

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

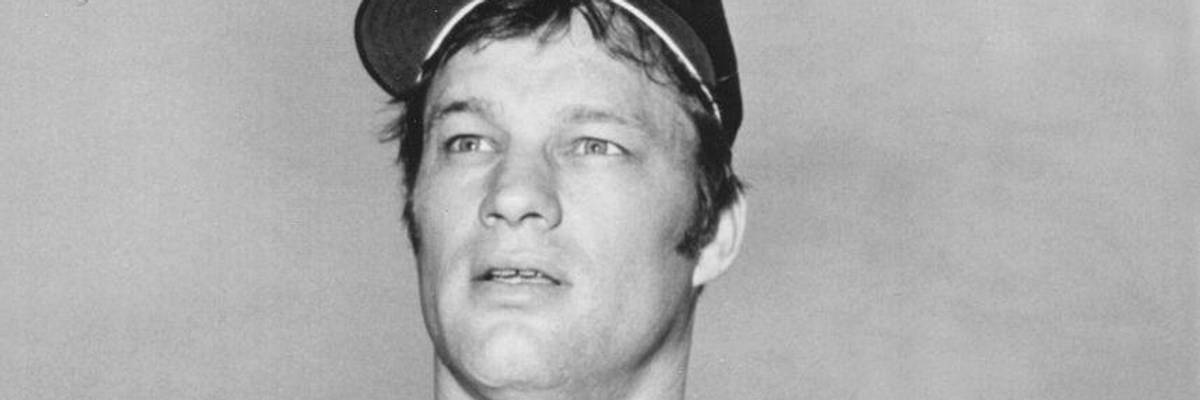

Baseball player and social justice activist Jim Bouton, then playing with the Houston Astros, poses during a break in spring training at Cocao Beach, Florida in 1970.

For Major League owners, the real threat of the free-thinking pitching great was how he challenged their economic power and, more broadly, America's unequal economic system and the undue influence of big corporations.

Amidst the current upsurge of social activism among professional athletes, it is worth recalling the enormous contribution of Jim Bouton, one of the most politically outspoken sports figures in American history. Among professional team sports, baseball may be the most conservative and tradition-bound, but throughout its history, rebels and mavericks have emerged to challenge the status quo in baseball and the wider society, none more so than Bouton.

During his playing days in the 1960s, Bouton spoke out against the Vietnam War, South African apartheid, the exploitation of players by greedy owners, and the casual racism of the teams and his fellow players. When his baseball career ended, he continued to use his celebrity as a platform against social injustice. He also worked as a newscaster, a movie and TV actor, and an advocate for restoring old baseball parks. He died in 2019 at age 80.

Bouton’s baseball memoir, Ball Four—published in 1970—may be the most influential sports book ever written. It was the only sports book to make the New York Public Library’s 1996 list of Books of the Century. Time magazine listed Ball Four as one of the 100 greatest non-fiction books of all time.

Bouton wrote Ball Four after his best days as a hard-throwing All-Star pitcher with the New York Yankees were over and he was trying to make a comeback as a knuckleball pitcher. He wanted athletes to speak out for themselves, to refuse to conform, and to defy complacency. Following his own advice, he was an early supporter of anti-Vietnam War presidential candidate Senator Eugene McCarthy in 1968 and he served as a Democratic Party convention delegate for anti-war presidential candidate Senator George McGovern in 1972.

In Ball Four, Bouton accused organized baseball of hypocrisy: portraying a squeaky-clean image while ignoring burning social issues. Bouton condemned baseball’s support for the Vietnam War. He attacked icons such as the Reverend Billy Graham, disputing his claim that communists had organized anti-war protests. While Baseball Commissioner Bowie Kuhn said he couldn’t remember any players being ostracized for anti-war statements, Bouton recounted being repeatedly heckled for his anti-war views by players and fans: “They wanted to know if I was working for Ho Chi Minh.”

On Saturday, September 18, 2010, Bouton came to the Burbank Public Library from his home in New Jersey to discuss Ball Four, which had been published 40 years earlier.

A standing room-only crowd of 175 attended the event. Fortunately, award-winning documentary filmmaker Jon Leonoudakis was there to record Bouton’s remarks. In fact, it was Leonoudakis’ idea to celebrate the book’s 40th anniversary. As a result, the rest of us can imbibe Bouton’s wisdom, insights, and humor about his 10 years in the big leagues and his much longer career as a writer, newscaster, and social critic.

Bouton, who was among few big leaguers who went to college, joined the New York Yankees in 1962. The next year, he had a sensational season, going 21–7 with a 2.53 ERA plus 10 relief appearances. He emerged as one of baseball’s top young pitchers and appeared in that season’s All-Star Game. In 1964 he was 18–13 with a 3.02 ERA, led the league in starts, and won two World Series games.

That’s when Bouton began speaking out on social issues, and his teammates and Yankees management began regarding him as a flake. They found him too intelligent and outspoken for his own good, an outside agitator disturbing the status quo. He typically sat at the back of the team bus, reading! He was considered a free thinker, “which in those days was one step away from being a Communist, to conservative sports minds,” observed sportswriter Ron Kaplan.

The Yankees tolerated this until Bouton suddenly became a marginal performer in 1965. Probably from overuse the previous two years, Bouton began having arm problems and slipped to 4–15 with a 4.82 ERA as the Yankees dropped to sixth place. His ERA bounced back in 1966 to 2.69, but poor run support held his won-loss record to 3–8.

Bouton and his liberal opinions had become expendable. He stayed with the Yankees for a few more uneventful years until 1969, when he was traded to the lowly Seattle Pilots, in their first year as a major league team.

Ball Four is ostensibly a diary of his 1969 season as a pitcher with the Pilots and the Houston Astros, but the most memorable and controversial parts of the book deal with his years with the Yankees. Decades before baseball was rocked by scandal over steroids, Bouton disclosed players’ widespread use of amphetamines (aka “greenies.”). One of the most controversial parts of the book was his revelation that his Yankees teammate Mickey Mantle, whom sportswriters viewed as baseball’s golden boy, was an alcoholic who often blasted towering home runs while nursing a hangover. As Bouton told Fresh Air host Terry Gross during a 1986 radio interview, his portrayal of Mantle “wasn’t really even so much as a put-down of Mickey Mantle as it was a story of what a great athlete he was.”

Leonoudakis had read Ball Four when it first hit the bookstores. He was 12 years old, and, like many baseball fans, it forever changed his view of the sport.

“I learned about the unfair business of the game, the hypocrisy, the pettiness, the struggles, the failures, and that the guys on my baseball cards were real people,” Leonoudakis explained. “No one had ever presented the national pastime this way before, because it was taboo.”

He kept the book with him through high school, college, and adulthood, re-reading it and its various updates. When the book’s four-decade anniversary appeared on the horizon, Leonoudakis pitched the idea to celebrate the book to Terry Cannon, executive director for the Baseball Reliquary, a Pasadena-based group that celebrates baseball’s renegades and iconoclasts.

Bouton, who in 2001 had been inducted into the Reliquary’s Shrine of the Eternals – what he called “the people’s Hall of Fame” – accepted the invitation to participate in the gathering, which would reunite him with Greg Goossen and Tommy Davis (his teammates with the Pilots, a one-year wonder as a team). Ron Shelton, a former minor league player best known for writing and directing the 1988 film, “Bull Durham,” which earned him an Academy Award nomination for Best Original Screenplay, joined the discussion about the often-invisible aspects of pro baseball.

“I smile a lot when I think that people are still talking about the book 40 years later,” Bouton said in his opening remarks at the “Ball Four Turns 40” event. “I caught lightning in a bottle. I was in the right place at the right time.”

Bouton credited his Pilots teammates for providing many of the stories he recounted in the book.

“They were veterans. They’d been around. They were great storytellers. All I had to do was listen, and watch, and write it all down,” which he did, on the backs of envelopes, on hotel note pads, on airplane barf bags, and even on toilet paper.

“Ball Four Turns 40” is Leonoudakis’ love letter to his hero Bouton. It is a fascinating one-hour tour of Bouton’s mind. With remarkable honesty and humor, Bouton describes his up-and-down career, his colorful Pilots teammates (cast-offs at the end of their careers), how he wrote Ball Four from notes scribbled on scraps of paper in dugouts, hotel rooms, and airplanes, and the controversy that surrounded the book.

Funny, honest, and well-written, Ball Four revealed aspects of major league baseball that sportswriters and previous ballplayer memoirs had ignored. Bouton expressed his outrage at owners who exploited players and at players who showed disrespect for the game he loved. He didn’t hold back naming names or describing the lives and antics of ballplayers both on and off the field. It portrayed laudable characters and accomplishments, but also aspects of players’ heavy drinking, crass language and behavior, pep pills and drug use, conservative political views, questionable baseball smarts, anti-intellectualism, womanizing, voyeurism, and extramarital affairs.

Ball Four described boys being boys: human, fun-loving, vulnerable, and sometimes immature. That is, ballplayers were normal young men, with some special skills, but otherwise not necessarily idealistic heroes, as they had been portrayed by most sports reporters. Exposing what had always been under wraps generated a firestorm of protest from players, management, and sportswriters.

By today’s standards, the book is quite tame. But at the time, it was shocking. As Mitchell Nathanson explains in his 2020 biography, Bouton: The Life of a Baseball Original, Bouton’s fellow ballplayers were outraged that he had broken the code by revealing stories from the locker rooms and hotel rooms. Many fans were upset by Bouton’s revelations about the private lives of their favorite players.

Bouton was attacked by sportswriters, who viewed their job as protecting the integrity of the game and the private lives of the players whom they relied on for interviews and stories. In three successive anti-Bouton articles, the New York Daily News influential sports columnist Dick Young portrayed Bouton as a “social leper” and a “commie in baseball stirrups.”

The book’s critics focused on how it assaulted the sanctity of the locker room. But for MLB owners, Bouton’s real threat was challenging their economic power and, more broadly, America’s unequal economic system and the undue influence of big corporations. Bouton loved baseball, but not the baseball establishment which, he believed, took advantage of powerless, unorganized, and under-educated athletes.

In a clubhouse discussion one day when Bouton was still with the Yankees, his teammates claimed a fair minimum salary should range between $7,000 and $12,000. Bouton was scolded when he proposed $25,000, but he pointed out that: “…everyone in this room has a PhD in hitting or pitching. We’re in the top 600 in the world at what we do. In an industry that makes millions of dollars, and we have to sign whatever contract they give us? That’s insane.”

Playing before the ascendancy of the Major League Baseball Players Association (MLBPA), Bouton revealed in Ball Four that major leaguers led lives with little financial or professional security. The owners cared about nothing except their profits. They kept salaries indecently low, and traded or demoted even the most loyal players. At the time, under the reserve clause in every major league contract, ballplayers were little more than indentured servants, with no ability to negotiate with their team owners for better salaries, benefits, or working conditions. Salary negotiations were a farce, and most players couldn’t make a living on their baseball pay, despite generating millions in profits for owners. Except for the superstars, ballplayers led a vagabond, insecure existence.

By disclosing these conditions, Bouton thought fellow ballplayers would appreciate him blowing the whistle. Instead, they complained about him violating their privacy and tarnishing their reputations.

By the late 1960s, however, the MLBPA was beginning its assault on players’ peonage. In 1968, two years after Marvin Miller joined the union as executive director, the MLBPA negotiated the first-ever collective-bargaining agreement in professional sports. By 1975, the union had overturned the reserve clause. Miller claimed that Ball Four “played a significant role in the removal of baseball’s reserve clause,” which led to better working conditions, pensions, health care, and salaries.

“When people complain about the big salaries that players now make, I tell them that for 100 years the owners screwed the players. For the past 30 years, the players have screwed the owners,” Bouton said at the Burbank gathering. “The way I look at it, the players have 70 years to go!”

Not surprisingly, Bouton was excoriated by baseball officials, including Commissioner Bowie Kuhn, who called Ball Four “detrimental to baseball” and demanded a meeting with Bouton. Miller and union attorney Richard Moss joined Bouton at the meeting. The commissioner claimed that Bouton was undermining baseball, but Bouton responded: “You’re wrong… People will be more interested in baseball, not less… People are turned off by the phony goody-goody image.” Kuhn said Bouton owed “it to the game because it gave you what you have,” but Bouton protested: “I always gave baseball everything I had. Besides, baseball didn’t give me anything. I earned it.”

Kuhn ordered Bouton to release a statement saying he falsified or exaggerated his stories, but Bouton refused. When Kuhn told him to regard the meeting as a warning, Miller shot back: “A warning against what…against writing about baseball?… You can’t subject someone to future penalties on such vague criteria.” Kuhn told Bouton that he was going to issue a statement threatening players with punishment for any further writing like Ball Four. He told Bouton that he should remain silent. Again, Bouton refused.

As Bouton explained at the 2010 symposium, the controversy helped turn the book into a bestseller.

“The publisher originally only printed 5,000 copies,” Bouton said. “But when Kuhn attacked the book, lots of baseball fans were curious about what he didn’t want them to read. Sales really took off.” Since then, over 5.5 million copies of Ball Four have been sold.

The book’s success, Bouton told the crowd at the 2010 event, was “all about perspective.” He couldn’t have written the book, he explained, if was still an All-Star pitcher with the Yankees. But when he played with the ill-fated Pilots – a team of cast-offs from other big-league teams – he joined the ranks of the marginalized, which shaped his standpoint.

“If a president writes a book about life at the White House, and a doorman writes a book on the same subject, read the doorman’s book,” Bouton said.

Bouton’s book helped change sports writing. While the old-timers condemned Bouton, a new wave of writers abandoned the deification of ballplayers and instead looked for unconventional angles. George Foster of the Boston Globe called the book a “revolutionary manifesto.” New York Times writer David Halberstam observed that Bouton “has written… a book deep in the American vein, so deep in fact that it is by no means a sports book….. [A] comparable insider’s book about, say, the Congress of the United States, the Ford Motor Company, or the Joint Chiefs of Staff would be equally welcome.” According to Stephen Jay Gould, a Harvard paleontologist and baseball writer, Ball Four inaugurated a “post-modern Boutonian revolution,” revealing that “heroes were not always what they were thought to be, questioning the masculine ideal in the professional game, and encouraging the reader to look beyond the media’s interpretations.”

As MLB historian John Thorn later observed, Ball Four was “a political work, and a milestone in the generational divide that characterized the 1960s. It is the product of a widespread rebellion against both authority and received wisdom.”

In “Ball Four Turns 40,” Leonoudakis has fully captured Bouton’s spirit. The film is filled with 1970s images and music. The filmmaker appears as a newscaster explaining the historical context of Bouton’s life and times.

The film is Leonoudakis’ love letter to Bouton, who reciprocated in Ball Four’s final printing (in 2014) where he thanked Leonoudakis and the Baseball Reliquary for organizing the event.

Leonoudakis is more than a fan. He’s a fanatic. Eight years ago he started a Facebook page called “Ball Four Freaks.” Membership is like an exclusive cult. You have to pass a baseball test to join.

“Ball Four Turns 40” is just the latest of Leonoudakis’ baseball documentaries. He’s produced “Not Exactly Cooperstown” (about the Baseball Reliquary), “The Day the World Series Stopped” (about the 1986 Bay Area earthquake that interrupted the fall classic between the San Francisco Giants and Oakland A’s), and “Hano! A Century in the Bleachers” (about 90-year old sportswriter Arnold Hano, author of the classic “A Day in the Bleachers”).

Curious baseball fans can watch “Ball Four Turns 40” by subscribing (for $8) to Leonoudakis’ Patreon page and stream the film by joining the "Fan Zone” tier (there’s instructions pinned to the top of the home page for those wishing to see “Ball Four Turns 40”). This also gives them access to another 20 of his films as well as his monthly interviews with experts like baseball writers Marty Appel and Jean Hastings Ardell, Negro Leagues historian Phil Dixon, and pioneering female umpire Perry Barber.

Dear Common Dreams reader, The U.S. is on a fast track to authoritarianism like nothing I've ever seen. Meanwhile, corporate news outlets are utterly capitulating to Trump, twisting their coverage to avoid drawing his ire while lining up to stuff cash in his pockets. That's why I believe that Common Dreams is doing the best and most consequential reporting that we've ever done. Our small but mighty team is a progressive reporting powerhouse, covering the news every day that the corporate media never will. Our mission has always been simple: To inform. To inspire. And to ignite change for the common good. Now here's the key piece that I want all our readers to understand: None of this would be possible without your financial support. That's not just some fundraising cliche. It's the absolute and literal truth. We don't accept corporate advertising and never will. We don't have a paywall because we don't think people should be blocked from critical news based on their ability to pay. Everything we do is funded by the donations of readers like you. Will you donate now to help power the nonprofit, independent reporting of Common Dreams? Thank you for being a vital member of our community. Together, we can keep independent journalism alive when it’s needed most. - Craig Brown, Co-founder |

Amidst the current upsurge of social activism among professional athletes, it is worth recalling the enormous contribution of Jim Bouton, one of the most politically outspoken sports figures in American history. Among professional team sports, baseball may be the most conservative and tradition-bound, but throughout its history, rebels and mavericks have emerged to challenge the status quo in baseball and the wider society, none more so than Bouton.

During his playing days in the 1960s, Bouton spoke out against the Vietnam War, South African apartheid, the exploitation of players by greedy owners, and the casual racism of the teams and his fellow players. When his baseball career ended, he continued to use his celebrity as a platform against social injustice. He also worked as a newscaster, a movie and TV actor, and an advocate for restoring old baseball parks. He died in 2019 at age 80.

Bouton’s baseball memoir, Ball Four—published in 1970—may be the most influential sports book ever written. It was the only sports book to make the New York Public Library’s 1996 list of Books of the Century. Time magazine listed Ball Four as one of the 100 greatest non-fiction books of all time.

Bouton wrote Ball Four after his best days as a hard-throwing All-Star pitcher with the New York Yankees were over and he was trying to make a comeback as a knuckleball pitcher. He wanted athletes to speak out for themselves, to refuse to conform, and to defy complacency. Following his own advice, he was an early supporter of anti-Vietnam War presidential candidate Senator Eugene McCarthy in 1968 and he served as a Democratic Party convention delegate for anti-war presidential candidate Senator George McGovern in 1972.

In Ball Four, Bouton accused organized baseball of hypocrisy: portraying a squeaky-clean image while ignoring burning social issues. Bouton condemned baseball’s support for the Vietnam War. He attacked icons such as the Reverend Billy Graham, disputing his claim that communists had organized anti-war protests. While Baseball Commissioner Bowie Kuhn said he couldn’t remember any players being ostracized for anti-war statements, Bouton recounted being repeatedly heckled for his anti-war views by players and fans: “They wanted to know if I was working for Ho Chi Minh.”

On Saturday, September 18, 2010, Bouton came to the Burbank Public Library from his home in New Jersey to discuss Ball Four, which had been published 40 years earlier.

A standing room-only crowd of 175 attended the event. Fortunately, award-winning documentary filmmaker Jon Leonoudakis was there to record Bouton’s remarks. In fact, it was Leonoudakis’ idea to celebrate the book’s 40th anniversary. As a result, the rest of us can imbibe Bouton’s wisdom, insights, and humor about his 10 years in the big leagues and his much longer career as a writer, newscaster, and social critic.

Bouton, who was among few big leaguers who went to college, joined the New York Yankees in 1962. The next year, he had a sensational season, going 21–7 with a 2.53 ERA plus 10 relief appearances. He emerged as one of baseball’s top young pitchers and appeared in that season’s All-Star Game. In 1964 he was 18–13 with a 3.02 ERA, led the league in starts, and won two World Series games.

That’s when Bouton began speaking out on social issues, and his teammates and Yankees management began regarding him as a flake. They found him too intelligent and outspoken for his own good, an outside agitator disturbing the status quo. He typically sat at the back of the team bus, reading! He was considered a free thinker, “which in those days was one step away from being a Communist, to conservative sports minds,” observed sportswriter Ron Kaplan.

The Yankees tolerated this until Bouton suddenly became a marginal performer in 1965. Probably from overuse the previous two years, Bouton began having arm problems and slipped to 4–15 with a 4.82 ERA as the Yankees dropped to sixth place. His ERA bounced back in 1966 to 2.69, but poor run support held his won-loss record to 3–8.

Bouton and his liberal opinions had become expendable. He stayed with the Yankees for a few more uneventful years until 1969, when he was traded to the lowly Seattle Pilots, in their first year as a major league team.

Ball Four is ostensibly a diary of his 1969 season as a pitcher with the Pilots and the Houston Astros, but the most memorable and controversial parts of the book deal with his years with the Yankees. Decades before baseball was rocked by scandal over steroids, Bouton disclosed players’ widespread use of amphetamines (aka “greenies.”). One of the most controversial parts of the book was his revelation that his Yankees teammate Mickey Mantle, whom sportswriters viewed as baseball’s golden boy, was an alcoholic who often blasted towering home runs while nursing a hangover. As Bouton told Fresh Air host Terry Gross during a 1986 radio interview, his portrayal of Mantle “wasn’t really even so much as a put-down of Mickey Mantle as it was a story of what a great athlete he was.”

Leonoudakis had read Ball Four when it first hit the bookstores. He was 12 years old, and, like many baseball fans, it forever changed his view of the sport.

“I learned about the unfair business of the game, the hypocrisy, the pettiness, the struggles, the failures, and that the guys on my baseball cards were real people,” Leonoudakis explained. “No one had ever presented the national pastime this way before, because it was taboo.”

He kept the book with him through high school, college, and adulthood, re-reading it and its various updates. When the book’s four-decade anniversary appeared on the horizon, Leonoudakis pitched the idea to celebrate the book to Terry Cannon, executive director for the Baseball Reliquary, a Pasadena-based group that celebrates baseball’s renegades and iconoclasts.

Bouton, who in 2001 had been inducted into the Reliquary’s Shrine of the Eternals – what he called “the people’s Hall of Fame” – accepted the invitation to participate in the gathering, which would reunite him with Greg Goossen and Tommy Davis (his teammates with the Pilots, a one-year wonder as a team). Ron Shelton, a former minor league player best known for writing and directing the 1988 film, “Bull Durham,” which earned him an Academy Award nomination for Best Original Screenplay, joined the discussion about the often-invisible aspects of pro baseball.

“I smile a lot when I think that people are still talking about the book 40 years later,” Bouton said in his opening remarks at the “Ball Four Turns 40” event. “I caught lightning in a bottle. I was in the right place at the right time.”

Bouton credited his Pilots teammates for providing many of the stories he recounted in the book.

“They were veterans. They’d been around. They were great storytellers. All I had to do was listen, and watch, and write it all down,” which he did, on the backs of envelopes, on hotel note pads, on airplane barf bags, and even on toilet paper.

“Ball Four Turns 40” is Leonoudakis’ love letter to his hero Bouton. It is a fascinating one-hour tour of Bouton’s mind. With remarkable honesty and humor, Bouton describes his up-and-down career, his colorful Pilots teammates (cast-offs at the end of their careers), how he wrote Ball Four from notes scribbled on scraps of paper in dugouts, hotel rooms, and airplanes, and the controversy that surrounded the book.

Funny, honest, and well-written, Ball Four revealed aspects of major league baseball that sportswriters and previous ballplayer memoirs had ignored. Bouton expressed his outrage at owners who exploited players and at players who showed disrespect for the game he loved. He didn’t hold back naming names or describing the lives and antics of ballplayers both on and off the field. It portrayed laudable characters and accomplishments, but also aspects of players’ heavy drinking, crass language and behavior, pep pills and drug use, conservative political views, questionable baseball smarts, anti-intellectualism, womanizing, voyeurism, and extramarital affairs.

Ball Four described boys being boys: human, fun-loving, vulnerable, and sometimes immature. That is, ballplayers were normal young men, with some special skills, but otherwise not necessarily idealistic heroes, as they had been portrayed by most sports reporters. Exposing what had always been under wraps generated a firestorm of protest from players, management, and sportswriters.

By today’s standards, the book is quite tame. But at the time, it was shocking. As Mitchell Nathanson explains in his 2020 biography, Bouton: The Life of a Baseball Original, Bouton’s fellow ballplayers were outraged that he had broken the code by revealing stories from the locker rooms and hotel rooms. Many fans were upset by Bouton’s revelations about the private lives of their favorite players.

Bouton was attacked by sportswriters, who viewed their job as protecting the integrity of the game and the private lives of the players whom they relied on for interviews and stories. In three successive anti-Bouton articles, the New York Daily News influential sports columnist Dick Young portrayed Bouton as a “social leper” and a “commie in baseball stirrups.”

The book’s critics focused on how it assaulted the sanctity of the locker room. But for MLB owners, Bouton’s real threat was challenging their economic power and, more broadly, America’s unequal economic system and the undue influence of big corporations. Bouton loved baseball, but not the baseball establishment which, he believed, took advantage of powerless, unorganized, and under-educated athletes.

In a clubhouse discussion one day when Bouton was still with the Yankees, his teammates claimed a fair minimum salary should range between $7,000 and $12,000. Bouton was scolded when he proposed $25,000, but he pointed out that: “…everyone in this room has a PhD in hitting or pitching. We’re in the top 600 in the world at what we do. In an industry that makes millions of dollars, and we have to sign whatever contract they give us? That’s insane.”

Playing before the ascendancy of the Major League Baseball Players Association (MLBPA), Bouton revealed in Ball Four that major leaguers led lives with little financial or professional security. The owners cared about nothing except their profits. They kept salaries indecently low, and traded or demoted even the most loyal players. At the time, under the reserve clause in every major league contract, ballplayers were little more than indentured servants, with no ability to negotiate with their team owners for better salaries, benefits, or working conditions. Salary negotiations were a farce, and most players couldn’t make a living on their baseball pay, despite generating millions in profits for owners. Except for the superstars, ballplayers led a vagabond, insecure existence.

By disclosing these conditions, Bouton thought fellow ballplayers would appreciate him blowing the whistle. Instead, they complained about him violating their privacy and tarnishing their reputations.

By the late 1960s, however, the MLBPA was beginning its assault on players’ peonage. In 1968, two years after Marvin Miller joined the union as executive director, the MLBPA negotiated the first-ever collective-bargaining agreement in professional sports. By 1975, the union had overturned the reserve clause. Miller claimed that Ball Four “played a significant role in the removal of baseball’s reserve clause,” which led to better working conditions, pensions, health care, and salaries.

“When people complain about the big salaries that players now make, I tell them that for 100 years the owners screwed the players. For the past 30 years, the players have screwed the owners,” Bouton said at the Burbank gathering. “The way I look at it, the players have 70 years to go!”

Not surprisingly, Bouton was excoriated by baseball officials, including Commissioner Bowie Kuhn, who called Ball Four “detrimental to baseball” and demanded a meeting with Bouton. Miller and union attorney Richard Moss joined Bouton at the meeting. The commissioner claimed that Bouton was undermining baseball, but Bouton responded: “You’re wrong… People will be more interested in baseball, not less… People are turned off by the phony goody-goody image.” Kuhn said Bouton owed “it to the game because it gave you what you have,” but Bouton protested: “I always gave baseball everything I had. Besides, baseball didn’t give me anything. I earned it.”

Kuhn ordered Bouton to release a statement saying he falsified or exaggerated his stories, but Bouton refused. When Kuhn told him to regard the meeting as a warning, Miller shot back: “A warning against what…against writing about baseball?… You can’t subject someone to future penalties on such vague criteria.” Kuhn told Bouton that he was going to issue a statement threatening players with punishment for any further writing like Ball Four. He told Bouton that he should remain silent. Again, Bouton refused.

As Bouton explained at the 2010 symposium, the controversy helped turn the book into a bestseller.

“The publisher originally only printed 5,000 copies,” Bouton said. “But when Kuhn attacked the book, lots of baseball fans were curious about what he didn’t want them to read. Sales really took off.” Since then, over 5.5 million copies of Ball Four have been sold.

The book’s success, Bouton told the crowd at the 2010 event, was “all about perspective.” He couldn’t have written the book, he explained, if was still an All-Star pitcher with the Yankees. But when he played with the ill-fated Pilots – a team of cast-offs from other big-league teams – he joined the ranks of the marginalized, which shaped his standpoint.

“If a president writes a book about life at the White House, and a doorman writes a book on the same subject, read the doorman’s book,” Bouton said.

Bouton’s book helped change sports writing. While the old-timers condemned Bouton, a new wave of writers abandoned the deification of ballplayers and instead looked for unconventional angles. George Foster of the Boston Globe called the book a “revolutionary manifesto.” New York Times writer David Halberstam observed that Bouton “has written… a book deep in the American vein, so deep in fact that it is by no means a sports book….. [A] comparable insider’s book about, say, the Congress of the United States, the Ford Motor Company, or the Joint Chiefs of Staff would be equally welcome.” According to Stephen Jay Gould, a Harvard paleontologist and baseball writer, Ball Four inaugurated a “post-modern Boutonian revolution,” revealing that “heroes were not always what they were thought to be, questioning the masculine ideal in the professional game, and encouraging the reader to look beyond the media’s interpretations.”

As MLB historian John Thorn later observed, Ball Four was “a political work, and a milestone in the generational divide that characterized the 1960s. It is the product of a widespread rebellion against both authority and received wisdom.”

In “Ball Four Turns 40,” Leonoudakis has fully captured Bouton’s spirit. The film is filled with 1970s images and music. The filmmaker appears as a newscaster explaining the historical context of Bouton’s life and times.

The film is Leonoudakis’ love letter to Bouton, who reciprocated in Ball Four’s final printing (in 2014) where he thanked Leonoudakis and the Baseball Reliquary for organizing the event.

Leonoudakis is more than a fan. He’s a fanatic. Eight years ago he started a Facebook page called “Ball Four Freaks.” Membership is like an exclusive cult. You have to pass a baseball test to join.

“Ball Four Turns 40” is just the latest of Leonoudakis’ baseball documentaries. He’s produced “Not Exactly Cooperstown” (about the Baseball Reliquary), “The Day the World Series Stopped” (about the 1986 Bay Area earthquake that interrupted the fall classic between the San Francisco Giants and Oakland A’s), and “Hano! A Century in the Bleachers” (about 90-year old sportswriter Arnold Hano, author of the classic “A Day in the Bleachers”).

Curious baseball fans can watch “Ball Four Turns 40” by subscribing (for $8) to Leonoudakis’ Patreon page and stream the film by joining the "Fan Zone” tier (there’s instructions pinned to the top of the home page for those wishing to see “Ball Four Turns 40”). This also gives them access to another 20 of his films as well as his monthly interviews with experts like baseball writers Marty Appel and Jean Hastings Ardell, Negro Leagues historian Phil Dixon, and pioneering female umpire Perry Barber.

Amidst the current upsurge of social activism among professional athletes, it is worth recalling the enormous contribution of Jim Bouton, one of the most politically outspoken sports figures in American history. Among professional team sports, baseball may be the most conservative and tradition-bound, but throughout its history, rebels and mavericks have emerged to challenge the status quo in baseball and the wider society, none more so than Bouton.

During his playing days in the 1960s, Bouton spoke out against the Vietnam War, South African apartheid, the exploitation of players by greedy owners, and the casual racism of the teams and his fellow players. When his baseball career ended, he continued to use his celebrity as a platform against social injustice. He also worked as a newscaster, a movie and TV actor, and an advocate for restoring old baseball parks. He died in 2019 at age 80.

Bouton’s baseball memoir, Ball Four—published in 1970—may be the most influential sports book ever written. It was the only sports book to make the New York Public Library’s 1996 list of Books of the Century. Time magazine listed Ball Four as one of the 100 greatest non-fiction books of all time.

Bouton wrote Ball Four after his best days as a hard-throwing All-Star pitcher with the New York Yankees were over and he was trying to make a comeback as a knuckleball pitcher. He wanted athletes to speak out for themselves, to refuse to conform, and to defy complacency. Following his own advice, he was an early supporter of anti-Vietnam War presidential candidate Senator Eugene McCarthy in 1968 and he served as a Democratic Party convention delegate for anti-war presidential candidate Senator George McGovern in 1972.

In Ball Four, Bouton accused organized baseball of hypocrisy: portraying a squeaky-clean image while ignoring burning social issues. Bouton condemned baseball’s support for the Vietnam War. He attacked icons such as the Reverend Billy Graham, disputing his claim that communists had organized anti-war protests. While Baseball Commissioner Bowie Kuhn said he couldn’t remember any players being ostracized for anti-war statements, Bouton recounted being repeatedly heckled for his anti-war views by players and fans: “They wanted to know if I was working for Ho Chi Minh.”

On Saturday, September 18, 2010, Bouton came to the Burbank Public Library from his home in New Jersey to discuss Ball Four, which had been published 40 years earlier.

A standing room-only crowd of 175 attended the event. Fortunately, award-winning documentary filmmaker Jon Leonoudakis was there to record Bouton’s remarks. In fact, it was Leonoudakis’ idea to celebrate the book’s 40th anniversary. As a result, the rest of us can imbibe Bouton’s wisdom, insights, and humor about his 10 years in the big leagues and his much longer career as a writer, newscaster, and social critic.

Bouton, who was among few big leaguers who went to college, joined the New York Yankees in 1962. The next year, he had a sensational season, going 21–7 with a 2.53 ERA plus 10 relief appearances. He emerged as one of baseball’s top young pitchers and appeared in that season’s All-Star Game. In 1964 he was 18–13 with a 3.02 ERA, led the league in starts, and won two World Series games.

That’s when Bouton began speaking out on social issues, and his teammates and Yankees management began regarding him as a flake. They found him too intelligent and outspoken for his own good, an outside agitator disturbing the status quo. He typically sat at the back of the team bus, reading! He was considered a free thinker, “which in those days was one step away from being a Communist, to conservative sports minds,” observed sportswriter Ron Kaplan.

The Yankees tolerated this until Bouton suddenly became a marginal performer in 1965. Probably from overuse the previous two years, Bouton began having arm problems and slipped to 4–15 with a 4.82 ERA as the Yankees dropped to sixth place. His ERA bounced back in 1966 to 2.69, but poor run support held his won-loss record to 3–8.

Bouton and his liberal opinions had become expendable. He stayed with the Yankees for a few more uneventful years until 1969, when he was traded to the lowly Seattle Pilots, in their first year as a major league team.

Ball Four is ostensibly a diary of his 1969 season as a pitcher with the Pilots and the Houston Astros, but the most memorable and controversial parts of the book deal with his years with the Yankees. Decades before baseball was rocked by scandal over steroids, Bouton disclosed players’ widespread use of amphetamines (aka “greenies.”). One of the most controversial parts of the book was his revelation that his Yankees teammate Mickey Mantle, whom sportswriters viewed as baseball’s golden boy, was an alcoholic who often blasted towering home runs while nursing a hangover. As Bouton told Fresh Air host Terry Gross during a 1986 radio interview, his portrayal of Mantle “wasn’t really even so much as a put-down of Mickey Mantle as it was a story of what a great athlete he was.”

Leonoudakis had read Ball Four when it first hit the bookstores. He was 12 years old, and, like many baseball fans, it forever changed his view of the sport.

“I learned about the unfair business of the game, the hypocrisy, the pettiness, the struggles, the failures, and that the guys on my baseball cards were real people,” Leonoudakis explained. “No one had ever presented the national pastime this way before, because it was taboo.”

He kept the book with him through high school, college, and adulthood, re-reading it and its various updates. When the book’s four-decade anniversary appeared on the horizon, Leonoudakis pitched the idea to celebrate the book to Terry Cannon, executive director for the Baseball Reliquary, a Pasadena-based group that celebrates baseball’s renegades and iconoclasts.

Bouton, who in 2001 had been inducted into the Reliquary’s Shrine of the Eternals – what he called “the people’s Hall of Fame” – accepted the invitation to participate in the gathering, which would reunite him with Greg Goossen and Tommy Davis (his teammates with the Pilots, a one-year wonder as a team). Ron Shelton, a former minor league player best known for writing and directing the 1988 film, “Bull Durham,” which earned him an Academy Award nomination for Best Original Screenplay, joined the discussion about the often-invisible aspects of pro baseball.

“I smile a lot when I think that people are still talking about the book 40 years later,” Bouton said in his opening remarks at the “Ball Four Turns 40” event. “I caught lightning in a bottle. I was in the right place at the right time.”

Bouton credited his Pilots teammates for providing many of the stories he recounted in the book.

“They were veterans. They’d been around. They were great storytellers. All I had to do was listen, and watch, and write it all down,” which he did, on the backs of envelopes, on hotel note pads, on airplane barf bags, and even on toilet paper.

“Ball Four Turns 40” is Leonoudakis’ love letter to his hero Bouton. It is a fascinating one-hour tour of Bouton’s mind. With remarkable honesty and humor, Bouton describes his up-and-down career, his colorful Pilots teammates (cast-offs at the end of their careers), how he wrote Ball Four from notes scribbled on scraps of paper in dugouts, hotel rooms, and airplanes, and the controversy that surrounded the book.

Funny, honest, and well-written, Ball Four revealed aspects of major league baseball that sportswriters and previous ballplayer memoirs had ignored. Bouton expressed his outrage at owners who exploited players and at players who showed disrespect for the game he loved. He didn’t hold back naming names or describing the lives and antics of ballplayers both on and off the field. It portrayed laudable characters and accomplishments, but also aspects of players’ heavy drinking, crass language and behavior, pep pills and drug use, conservative political views, questionable baseball smarts, anti-intellectualism, womanizing, voyeurism, and extramarital affairs.

Ball Four described boys being boys: human, fun-loving, vulnerable, and sometimes immature. That is, ballplayers were normal young men, with some special skills, but otherwise not necessarily idealistic heroes, as they had been portrayed by most sports reporters. Exposing what had always been under wraps generated a firestorm of protest from players, management, and sportswriters.

By today’s standards, the book is quite tame. But at the time, it was shocking. As Mitchell Nathanson explains in his 2020 biography, Bouton: The Life of a Baseball Original, Bouton’s fellow ballplayers were outraged that he had broken the code by revealing stories from the locker rooms and hotel rooms. Many fans were upset by Bouton’s revelations about the private lives of their favorite players.

Bouton was attacked by sportswriters, who viewed their job as protecting the integrity of the game and the private lives of the players whom they relied on for interviews and stories. In three successive anti-Bouton articles, the New York Daily News influential sports columnist Dick Young portrayed Bouton as a “social leper” and a “commie in baseball stirrups.”

The book’s critics focused on how it assaulted the sanctity of the locker room. But for MLB owners, Bouton’s real threat was challenging their economic power and, more broadly, America’s unequal economic system and the undue influence of big corporations. Bouton loved baseball, but not the baseball establishment which, he believed, took advantage of powerless, unorganized, and under-educated athletes.

In a clubhouse discussion one day when Bouton was still with the Yankees, his teammates claimed a fair minimum salary should range between $7,000 and $12,000. Bouton was scolded when he proposed $25,000, but he pointed out that: “…everyone in this room has a PhD in hitting or pitching. We’re in the top 600 in the world at what we do. In an industry that makes millions of dollars, and we have to sign whatever contract they give us? That’s insane.”

Playing before the ascendancy of the Major League Baseball Players Association (MLBPA), Bouton revealed in Ball Four that major leaguers led lives with little financial or professional security. The owners cared about nothing except their profits. They kept salaries indecently low, and traded or demoted even the most loyal players. At the time, under the reserve clause in every major league contract, ballplayers were little more than indentured servants, with no ability to negotiate with their team owners for better salaries, benefits, or working conditions. Salary negotiations were a farce, and most players couldn’t make a living on their baseball pay, despite generating millions in profits for owners. Except for the superstars, ballplayers led a vagabond, insecure existence.

By disclosing these conditions, Bouton thought fellow ballplayers would appreciate him blowing the whistle. Instead, they complained about him violating their privacy and tarnishing their reputations.

By the late 1960s, however, the MLBPA was beginning its assault on players’ peonage. In 1968, two years after Marvin Miller joined the union as executive director, the MLBPA negotiated the first-ever collective-bargaining agreement in professional sports. By 1975, the union had overturned the reserve clause. Miller claimed that Ball Four “played a significant role in the removal of baseball’s reserve clause,” which led to better working conditions, pensions, health care, and salaries.

“When people complain about the big salaries that players now make, I tell them that for 100 years the owners screwed the players. For the past 30 years, the players have screwed the owners,” Bouton said at the Burbank gathering. “The way I look at it, the players have 70 years to go!”

Not surprisingly, Bouton was excoriated by baseball officials, including Commissioner Bowie Kuhn, who called Ball Four “detrimental to baseball” and demanded a meeting with Bouton. Miller and union attorney Richard Moss joined Bouton at the meeting. The commissioner claimed that Bouton was undermining baseball, but Bouton responded: “You’re wrong… People will be more interested in baseball, not less… People are turned off by the phony goody-goody image.” Kuhn said Bouton owed “it to the game because it gave you what you have,” but Bouton protested: “I always gave baseball everything I had. Besides, baseball didn’t give me anything. I earned it.”

Kuhn ordered Bouton to release a statement saying he falsified or exaggerated his stories, but Bouton refused. When Kuhn told him to regard the meeting as a warning, Miller shot back: “A warning against what…against writing about baseball?… You can’t subject someone to future penalties on such vague criteria.” Kuhn told Bouton that he was going to issue a statement threatening players with punishment for any further writing like Ball Four. He told Bouton that he should remain silent. Again, Bouton refused.

As Bouton explained at the 2010 symposium, the controversy helped turn the book into a bestseller.

“The publisher originally only printed 5,000 copies,” Bouton said. “But when Kuhn attacked the book, lots of baseball fans were curious about what he didn’t want them to read. Sales really took off.” Since then, over 5.5 million copies of Ball Four have been sold.

The book’s success, Bouton told the crowd at the 2010 event, was “all about perspective.” He couldn’t have written the book, he explained, if was still an All-Star pitcher with the Yankees. But when he played with the ill-fated Pilots – a team of cast-offs from other big-league teams – he joined the ranks of the marginalized, which shaped his standpoint.

“If a president writes a book about life at the White House, and a doorman writes a book on the same subject, read the doorman’s book,” Bouton said.

Bouton’s book helped change sports writing. While the old-timers condemned Bouton, a new wave of writers abandoned the deification of ballplayers and instead looked for unconventional angles. George Foster of the Boston Globe called the book a “revolutionary manifesto.” New York Times writer David Halberstam observed that Bouton “has written… a book deep in the American vein, so deep in fact that it is by no means a sports book….. [A] comparable insider’s book about, say, the Congress of the United States, the Ford Motor Company, or the Joint Chiefs of Staff would be equally welcome.” According to Stephen Jay Gould, a Harvard paleontologist and baseball writer, Ball Four inaugurated a “post-modern Boutonian revolution,” revealing that “heroes were not always what they were thought to be, questioning the masculine ideal in the professional game, and encouraging the reader to look beyond the media’s interpretations.”

As MLB historian John Thorn later observed, Ball Four was “a political work, and a milestone in the generational divide that characterized the 1960s. It is the product of a widespread rebellion against both authority and received wisdom.”

In “Ball Four Turns 40,” Leonoudakis has fully captured Bouton’s spirit. The film is filled with 1970s images and music. The filmmaker appears as a newscaster explaining the historical context of Bouton’s life and times.

The film is Leonoudakis’ love letter to Bouton, who reciprocated in Ball Four’s final printing (in 2014) where he thanked Leonoudakis and the Baseball Reliquary for organizing the event.

Leonoudakis is more than a fan. He’s a fanatic. Eight years ago he started a Facebook page called “Ball Four Freaks.” Membership is like an exclusive cult. You have to pass a baseball test to join.

“Ball Four Turns 40” is just the latest of Leonoudakis’ baseball documentaries. He’s produced “Not Exactly Cooperstown” (about the Baseball Reliquary), “The Day the World Series Stopped” (about the 1986 Bay Area earthquake that interrupted the fall classic between the San Francisco Giants and Oakland A’s), and “Hano! A Century in the Bleachers” (about 90-year old sportswriter Arnold Hano, author of the classic “A Day in the Bleachers”).

Curious baseball fans can watch “Ball Four Turns 40” by subscribing (for $8) to Leonoudakis’ Patreon page and stream the film by joining the "Fan Zone” tier (there’s instructions pinned to the top of the home page for those wishing to see “Ball Four Turns 40”). This also gives them access to another 20 of his films as well as his monthly interviews with experts like baseball writers Marty Appel and Jean Hastings Ardell, Negro Leagues historian Phil Dixon, and pioneering female umpire Perry Barber.