SUBSCRIBE TO OUR FREE NEWSLETTER

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

5

#000000

#FFFFFF

To donate by check, phone, or other method, see our More Ways to Give page.

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

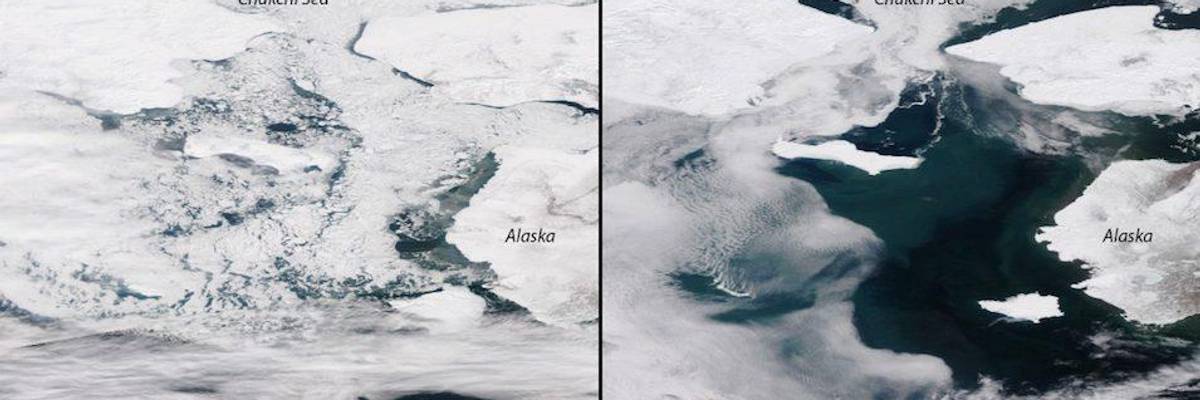

In March 2019, the Bering Sea had less ice than in April 2014. (Photo: U.S. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration)

Alaska's on thin ice.

That's according to reporting in Hakai Magazine by environmentalist Tim Lydon, who looked at the effects of a warmer-than-average late winter in the northernmost state in the U.S.

"March temperatures averaged 11 degC above normal," said Lydon. "The deviation was most extreme in the Arctic where, on March 30, thermometers rose almost 22 degC above normal--to 3 degC . That still sounds cold, but it was comparatively hot."

The warmth is having a major impact on Alaskans, said climate specialist Rick Thoman, who works with the Alaska Center for Climate Assessment and Policy.

"It's hard to characterize that anomaly," said Thoman, "it's just pretty darn remarkable for that part of the world."

In March, climate scientist Zach Labe shared a map on Twitter showing the warming.

That heat thinned out the ice in Alaska, leading to deaths and a loss of infrastructure--the latter because, as Lydon put it, "in Alaska, ice is infrastructure."

For example, the Kuskokwim River, which runs over 1,100 kilometers across southwestern Alaska, freezes so solid that it becomes a marked ice road connecting dozens of communities spread over 300 kilometers. In sparsely populated interior Alaska, frozen rivers are indispensable for transporting goods, visiting family, and delivering kids to school basketball games.

Along Alaska's west coast, the frozen waters of the Bering Sea also act as infrastructure. Each winter, frigid air transforms much of the Bering between Russia and Alaska into sea ice. As it fastens to shore, the ice provides platforms for fishing and hunting, and safe routes between communities. It also prevents wave action and storm surges from eroding the shores of coastal villages.

Losing that critical component of life in the Arctic could be devastating. Already, said Lydon, thinning ice is claiming lives of Alaskans who are quite naturally expecting normal conditions. In the 2019 winter, at least eight people died when snowmobiles or four-wheelers they were using for transportation crashed through thin ice. And a lack of icepack is adding to lower than normal fish and crab counts as routes provided by the ice have disappeared.

"Continued warmth like this has cascading effects," biological oceanographer Rob Campbell told Lydon. "We may not understand the consequences for species like salmon for years to come."

Dear Common Dreams reader, The U.S. is on a fast track to authoritarianism like nothing I've ever seen. Meanwhile, corporate news outlets are utterly capitulating to Trump, twisting their coverage to avoid drawing his ire while lining up to stuff cash in his pockets. That's why I believe that Common Dreams is doing the best and most consequential reporting that we've ever done. Our small but mighty team is a progressive reporting powerhouse, covering the news every day that the corporate media never will. Our mission has always been simple: To inform. To inspire. And to ignite change for the common good. Now here's the key piece that I want all our readers to understand: None of this would be possible without your financial support. That's not just some fundraising cliche. It's the absolute and literal truth. We don't accept corporate advertising and never will. We don't have a paywall because we don't think people should be blocked from critical news based on their ability to pay. Everything we do is funded by the donations of readers like you. Will you donate now to help power the nonprofit, independent reporting of Common Dreams? Thank you for being a vital member of our community. Together, we can keep independent journalism alive when it’s needed most. - Craig Brown, Co-founder |

Alaska's on thin ice.

That's according to reporting in Hakai Magazine by environmentalist Tim Lydon, who looked at the effects of a warmer-than-average late winter in the northernmost state in the U.S.

"March temperatures averaged 11 degC above normal," said Lydon. "The deviation was most extreme in the Arctic where, on March 30, thermometers rose almost 22 degC above normal--to 3 degC . That still sounds cold, but it was comparatively hot."

The warmth is having a major impact on Alaskans, said climate specialist Rick Thoman, who works with the Alaska Center for Climate Assessment and Policy.

"It's hard to characterize that anomaly," said Thoman, "it's just pretty darn remarkable for that part of the world."

In March, climate scientist Zach Labe shared a map on Twitter showing the warming.

That heat thinned out the ice in Alaska, leading to deaths and a loss of infrastructure--the latter because, as Lydon put it, "in Alaska, ice is infrastructure."

For example, the Kuskokwim River, which runs over 1,100 kilometers across southwestern Alaska, freezes so solid that it becomes a marked ice road connecting dozens of communities spread over 300 kilometers. In sparsely populated interior Alaska, frozen rivers are indispensable for transporting goods, visiting family, and delivering kids to school basketball games.

Along Alaska's west coast, the frozen waters of the Bering Sea also act as infrastructure. Each winter, frigid air transforms much of the Bering between Russia and Alaska into sea ice. As it fastens to shore, the ice provides platforms for fishing and hunting, and safe routes between communities. It also prevents wave action and storm surges from eroding the shores of coastal villages.

Losing that critical component of life in the Arctic could be devastating. Already, said Lydon, thinning ice is claiming lives of Alaskans who are quite naturally expecting normal conditions. In the 2019 winter, at least eight people died when snowmobiles or four-wheelers they were using for transportation crashed through thin ice. And a lack of icepack is adding to lower than normal fish and crab counts as routes provided by the ice have disappeared.

"Continued warmth like this has cascading effects," biological oceanographer Rob Campbell told Lydon. "We may not understand the consequences for species like salmon for years to come."

Alaska's on thin ice.

That's according to reporting in Hakai Magazine by environmentalist Tim Lydon, who looked at the effects of a warmer-than-average late winter in the northernmost state in the U.S.

"March temperatures averaged 11 degC above normal," said Lydon. "The deviation was most extreme in the Arctic where, on March 30, thermometers rose almost 22 degC above normal--to 3 degC . That still sounds cold, but it was comparatively hot."

The warmth is having a major impact on Alaskans, said climate specialist Rick Thoman, who works with the Alaska Center for Climate Assessment and Policy.

"It's hard to characterize that anomaly," said Thoman, "it's just pretty darn remarkable for that part of the world."

In March, climate scientist Zach Labe shared a map on Twitter showing the warming.

That heat thinned out the ice in Alaska, leading to deaths and a loss of infrastructure--the latter because, as Lydon put it, "in Alaska, ice is infrastructure."

For example, the Kuskokwim River, which runs over 1,100 kilometers across southwestern Alaska, freezes so solid that it becomes a marked ice road connecting dozens of communities spread over 300 kilometers. In sparsely populated interior Alaska, frozen rivers are indispensable for transporting goods, visiting family, and delivering kids to school basketball games.

Along Alaska's west coast, the frozen waters of the Bering Sea also act as infrastructure. Each winter, frigid air transforms much of the Bering between Russia and Alaska into sea ice. As it fastens to shore, the ice provides platforms for fishing and hunting, and safe routes between communities. It also prevents wave action and storm surges from eroding the shores of coastal villages.

Losing that critical component of life in the Arctic could be devastating. Already, said Lydon, thinning ice is claiming lives of Alaskans who are quite naturally expecting normal conditions. In the 2019 winter, at least eight people died when snowmobiles or four-wheelers they were using for transportation crashed through thin ice. And a lack of icepack is adding to lower than normal fish and crab counts as routes provided by the ice have disappeared.

"Continued warmth like this has cascading effects," biological oceanographer Rob Campbell told Lydon. "We may not understand the consequences for species like salmon for years to come."