SUBSCRIBE TO OUR FREE NEWSLETTER

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

5

#000000

#FFFFFF

To donate by check, phone, or other method, see our More Ways to Give page.

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

Precisely 100 years after the deadly fact, long-traumatized black descendants of the 1921 Tulsa Massacre are marking, grieving, demanding reparations from and seeking to break a "conspiracy of silence" about one of the worst acts of mass racial violence in a country that's committed more than its share of it. Still beset by glaring racial disparity, the city remains "sacred land (but) also a crime scene" - especially for survivors who "still see smoke and smell fire."

The denizens of Black Wall Street

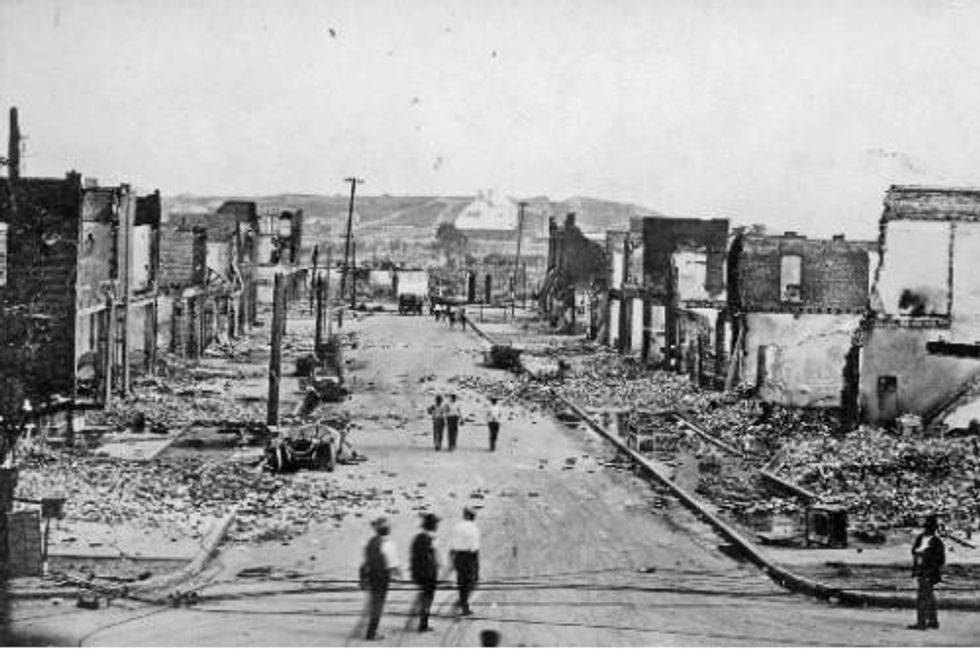

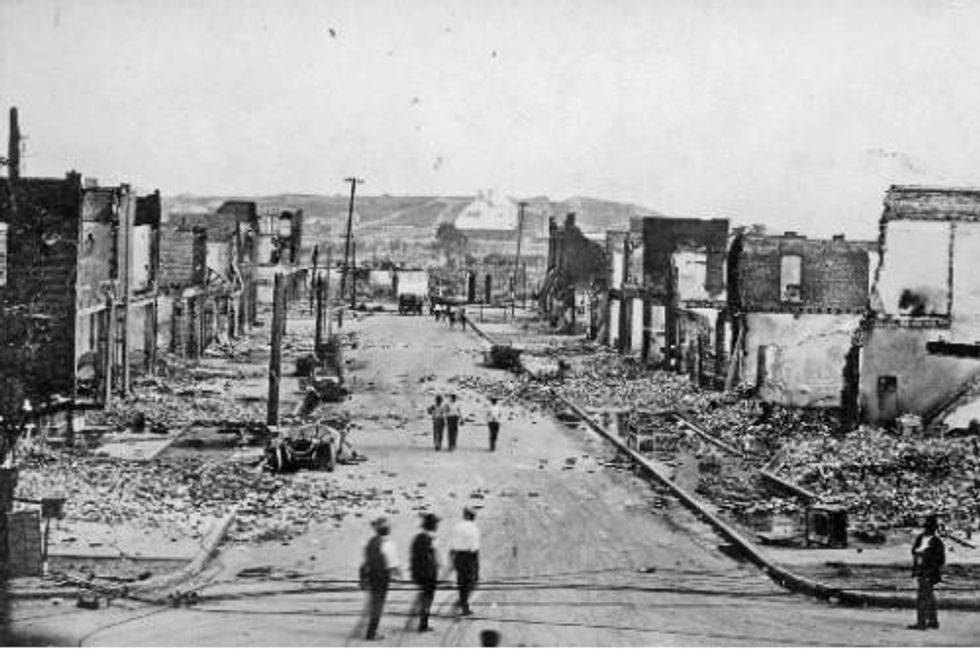

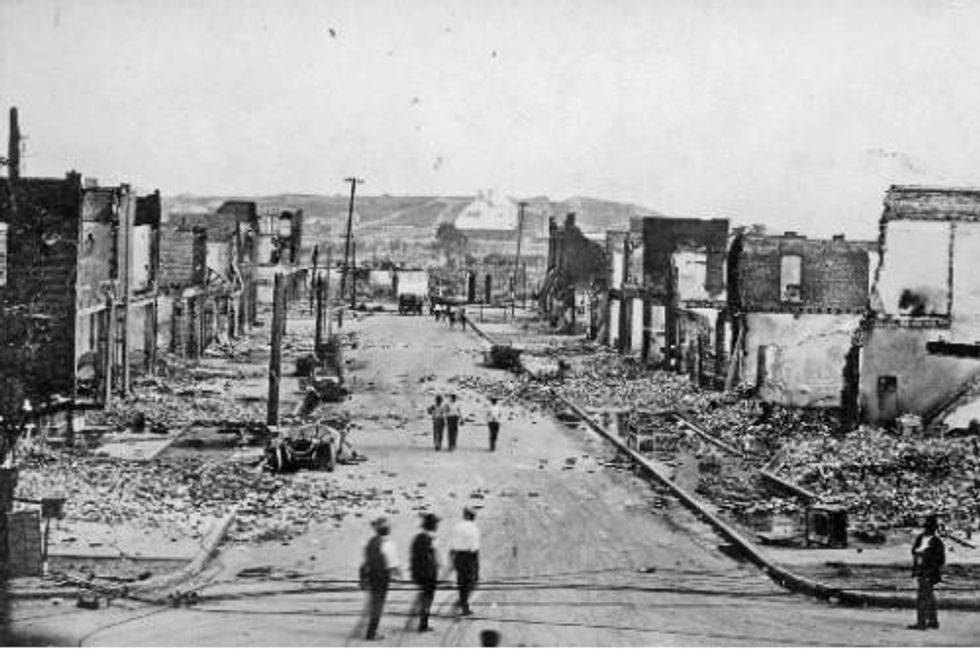

Precisely 100 years after the gruesome fact, traumatized black descendants of the 1921 Tulsa Massacre - long, infamously, tellingly deemed "a race riot" - are marking, grieving, demanding reparations from and seeking to break the "conspiracy of silence" around one of the most deadly acts of mass racial violence in a country that's committed more than its share of it. In a city still plagued by racial disparity, residents and officials have vowed to "remember and rise" with a host of events and initiatives aimed at "shining a light on one of the darkest days in America's history." Over 18 hours spanning May 31 and June 1, 1921, a savage white mob descended on the thriving, all-black North Tulsa neighborhood of Greenwood, known as "Black Wall Street," after they failed to lynch a young black shoeshiner who - shades of Emmett Till - may or may not have accidentally stepped on the foot of a white elevator attendant. In under 24 hours, they leveled more than 35 city blocks: White marauders, deputized by police and aided by white pilots dropping kerosene bombs from above, looted and burned over 1,200 black businesses, churches, homes, leaving 10,000 residents homeless. Over 300 black people were killed, and 800 were shot or wounded; witnesses described seeing dozens of black bodies dropped from bridges into the Arkansas River or thrown into unmarked graves. Still, headlines of the day shrieked, "Two Whites Dead in Race Riot" and "Race War Rages" in what was dubbed "Little Africa." After the fires were put out, insurance companies denied most of the black survivors' claims totaling about $1.8 million, or roughly $27 million today. No black victim or descendant was ever compensated, and no white person was punished or imprisoned for the violence.

For decades, the story of the massacre was virtually silenced - buried in city records, whitewashed in history books, skipped over in schools, with only small metal plaques to mark businesses destroyed and its victims relegated to "this country's corrosive amnesia" over race. But amidst the ongoing, if imperfect racial reckoning of recent years, and with the centennial approaching, a broad coalition of Tulsa groups undertook a campaign to commemorate the event as "a beacon of reconciliation." Its Centennial Commission - "Tulsa Triumphs" - raised $30 million and built a history center and museum, Greenwood Rising; a new Black Wall Street Times opened, and through May ran a series of cartoons about the massacre and its impact on black children - "Is the world on fire?"; hashtags - #Greenwood Rising and #Remember Tulsa - sprang up; Tulsa County Democrats called for the recognition of ongoing racism; this week's events include the belated exhuming of 12 massacre-era coffins from "where nobody is supposed to be buried." At the same time, hard truths about "reconciliation" - and the inadequacy of a museum to provide it - have also surfaced. Because saying you're sorry isn't the same as making amends for grievous, real-life losses, many have long argued that monetary reparations must be made for justice to be served and healing to begin. Now, three survivors - 107-year-old Viola Fletcher, 106-year-old Lessie Benningfield Randle and 100-year-old Hughes Van Ellis - and other victims' descendants are suing multiple city agencies under the state's public nuisance statute for reparations; they also seek to establish a victims' compensation fund to acknowledge, "This is sacred land, but it's also a crime scene."

With a black poverty rate over double that of whites, a history of police brutality, the 2016 killing of an unarmed Terence Crutcher, and an interstate in the middle of Tulsa re-enforcing de facto segregation, it's also what many black residents argue is "a continual massacre." "Tulsa is very much a microcosm," says the director of a new documentary about the 1921 massacre. "All the issues the country is continuing to confront or struggle with are writ large." Among descendants of the massacre, they're magnified by a keen awareness of the generational wealth lost to them, a sense "of where I could be versus where I am." Those tensions came into stark relief when Monday's big Remember & Rise event, featuring headliner John Legend and keynote speaker Stacey Abrams, was abruptly canceled after a squabble over reparations. A deal to pay just $100,000 to each survivor and $2 million in seed money for a descendants' fund fell apart after their lead attorney reportedly upped the amount to $1 million each and $50 million for the fund. Many supported the change, blasting the exploitation of survivors and their stories in the name of profit. "Yes, how dare (they) ask for 10% of the $30 MILLION raised by a committee that wants to display them onstage at an event ABOUT THEIR SUFFERING," fumed one, "expecting them to be grateful while the descendants of those who burned Greenwood to the ground keep profiting/exploiting them for tourism." For survivors, meanwhile, the trauma remains. Testifying recently about reparations, Viola Fletcher, the oldest survivor, told Congress, "I am here seeking justice" for a crime she relives every day: "I still see smoke and smell fire." 100 years later, with clear memories of the mob, she still sleeps sitting up on a couch with the lights on. "Being in the dark, I can't see how to get out," she said. "I can't see who is coming in."

Dear Common Dreams reader, The U.S. is on a fast track to authoritarianism like nothing I've ever seen. Meanwhile, corporate news outlets are utterly capitulating to Trump, twisting their coverage to avoid drawing his ire while lining up to stuff cash in his pockets. That's why I believe that Common Dreams is doing the best and most consequential reporting that we've ever done. Our small but mighty team is a progressive reporting powerhouse, covering the news every day that the corporate media never will. Our mission has always been simple: To inform. To inspire. And to ignite change for the common good. Now here's the key piece that I want all our readers to understand: None of this would be possible without your financial support. That's not just some fundraising cliche. It's the absolute and literal truth. We don't accept corporate advertising and never will. We don't have a paywall because we don't think people should be blocked from critical news based on their ability to pay. Everything we do is funded by the donations of readers like you. Will you donate now to help power the nonprofit, independent reporting of Common Dreams? Thank you for being a vital member of our community. Together, we can keep independent journalism alive when it’s needed most. - Craig Brown, Co-founder |

The denizens of Black Wall Street

Precisely 100 years after the gruesome fact, traumatized black descendants of the 1921 Tulsa Massacre - long, infamously, tellingly deemed "a race riot" - are marking, grieving, demanding reparations from and seeking to break the "conspiracy of silence" around one of the most deadly acts of mass racial violence in a country that's committed more than its share of it. In a city still plagued by racial disparity, residents and officials have vowed to "remember and rise" with a host of events and initiatives aimed at "shining a light on one of the darkest days in America's history." Over 18 hours spanning May 31 and June 1, 1921, a savage white mob descended on the thriving, all-black North Tulsa neighborhood of Greenwood, known as "Black Wall Street," after they failed to lynch a young black shoeshiner who - shades of Emmett Till - may or may not have accidentally stepped on the foot of a white elevator attendant. In under 24 hours, they leveled more than 35 city blocks: White marauders, deputized by police and aided by white pilots dropping kerosene bombs from above, looted and burned over 1,200 black businesses, churches, homes, leaving 10,000 residents homeless. Over 300 black people were killed, and 800 were shot or wounded; witnesses described seeing dozens of black bodies dropped from bridges into the Arkansas River or thrown into unmarked graves. Still, headlines of the day shrieked, "Two Whites Dead in Race Riot" and "Race War Rages" in what was dubbed "Little Africa." After the fires were put out, insurance companies denied most of the black survivors' claims totaling about $1.8 million, or roughly $27 million today. No black victim or descendant was ever compensated, and no white person was punished or imprisoned for the violence.

For decades, the story of the massacre was virtually silenced - buried in city records, whitewashed in history books, skipped over in schools, with only small metal plaques to mark businesses destroyed and its victims relegated to "this country's corrosive amnesia" over race. But amidst the ongoing, if imperfect racial reckoning of recent years, and with the centennial approaching, a broad coalition of Tulsa groups undertook a campaign to commemorate the event as "a beacon of reconciliation." Its Centennial Commission - "Tulsa Triumphs" - raised $30 million and built a history center and museum, Greenwood Rising; a new Black Wall Street Times opened, and through May ran a series of cartoons about the massacre and its impact on black children - "Is the world on fire?"; hashtags - #Greenwood Rising and #Remember Tulsa - sprang up; Tulsa County Democrats called for the recognition of ongoing racism; this week's events include the belated exhuming of 12 massacre-era coffins from "where nobody is supposed to be buried." At the same time, hard truths about "reconciliation" - and the inadequacy of a museum to provide it - have also surfaced. Because saying you're sorry isn't the same as making amends for grievous, real-life losses, many have long argued that monetary reparations must be made for justice to be served and healing to begin. Now, three survivors - 107-year-old Viola Fletcher, 106-year-old Lessie Benningfield Randle and 100-year-old Hughes Van Ellis - and other victims' descendants are suing multiple city agencies under the state's public nuisance statute for reparations; they also seek to establish a victims' compensation fund to acknowledge, "This is sacred land, but it's also a crime scene."

With a black poverty rate over double that of whites, a history of police brutality, the 2016 killing of an unarmed Terence Crutcher, and an interstate in the middle of Tulsa re-enforcing de facto segregation, it's also what many black residents argue is "a continual massacre." "Tulsa is very much a microcosm," says the director of a new documentary about the 1921 massacre. "All the issues the country is continuing to confront or struggle with are writ large." Among descendants of the massacre, they're magnified by a keen awareness of the generational wealth lost to them, a sense "of where I could be versus where I am." Those tensions came into stark relief when Monday's big Remember & Rise event, featuring headliner John Legend and keynote speaker Stacey Abrams, was abruptly canceled after a squabble over reparations. A deal to pay just $100,000 to each survivor and $2 million in seed money for a descendants' fund fell apart after their lead attorney reportedly upped the amount to $1 million each and $50 million for the fund. Many supported the change, blasting the exploitation of survivors and their stories in the name of profit. "Yes, how dare (they) ask for 10% of the $30 MILLION raised by a committee that wants to display them onstage at an event ABOUT THEIR SUFFERING," fumed one, "expecting them to be grateful while the descendants of those who burned Greenwood to the ground keep profiting/exploiting them for tourism." For survivors, meanwhile, the trauma remains. Testifying recently about reparations, Viola Fletcher, the oldest survivor, told Congress, "I am here seeking justice" for a crime she relives every day: "I still see smoke and smell fire." 100 years later, with clear memories of the mob, she still sleeps sitting up on a couch with the lights on. "Being in the dark, I can't see how to get out," she said. "I can't see who is coming in."

The denizens of Black Wall Street

Precisely 100 years after the gruesome fact, traumatized black descendants of the 1921 Tulsa Massacre - long, infamously, tellingly deemed "a race riot" - are marking, grieving, demanding reparations from and seeking to break the "conspiracy of silence" around one of the most deadly acts of mass racial violence in a country that's committed more than its share of it. In a city still plagued by racial disparity, residents and officials have vowed to "remember and rise" with a host of events and initiatives aimed at "shining a light on one of the darkest days in America's history." Over 18 hours spanning May 31 and June 1, 1921, a savage white mob descended on the thriving, all-black North Tulsa neighborhood of Greenwood, known as "Black Wall Street," after they failed to lynch a young black shoeshiner who - shades of Emmett Till - may or may not have accidentally stepped on the foot of a white elevator attendant. In under 24 hours, they leveled more than 35 city blocks: White marauders, deputized by police and aided by white pilots dropping kerosene bombs from above, looted and burned over 1,200 black businesses, churches, homes, leaving 10,000 residents homeless. Over 300 black people were killed, and 800 were shot or wounded; witnesses described seeing dozens of black bodies dropped from bridges into the Arkansas River or thrown into unmarked graves. Still, headlines of the day shrieked, "Two Whites Dead in Race Riot" and "Race War Rages" in what was dubbed "Little Africa." After the fires were put out, insurance companies denied most of the black survivors' claims totaling about $1.8 million, or roughly $27 million today. No black victim or descendant was ever compensated, and no white person was punished or imprisoned for the violence.

For decades, the story of the massacre was virtually silenced - buried in city records, whitewashed in history books, skipped over in schools, with only small metal plaques to mark businesses destroyed and its victims relegated to "this country's corrosive amnesia" over race. But amidst the ongoing, if imperfect racial reckoning of recent years, and with the centennial approaching, a broad coalition of Tulsa groups undertook a campaign to commemorate the event as "a beacon of reconciliation." Its Centennial Commission - "Tulsa Triumphs" - raised $30 million and built a history center and museum, Greenwood Rising; a new Black Wall Street Times opened, and through May ran a series of cartoons about the massacre and its impact on black children - "Is the world on fire?"; hashtags - #Greenwood Rising and #Remember Tulsa - sprang up; Tulsa County Democrats called for the recognition of ongoing racism; this week's events include the belated exhuming of 12 massacre-era coffins from "where nobody is supposed to be buried." At the same time, hard truths about "reconciliation" - and the inadequacy of a museum to provide it - have also surfaced. Because saying you're sorry isn't the same as making amends for grievous, real-life losses, many have long argued that monetary reparations must be made for justice to be served and healing to begin. Now, three survivors - 107-year-old Viola Fletcher, 106-year-old Lessie Benningfield Randle and 100-year-old Hughes Van Ellis - and other victims' descendants are suing multiple city agencies under the state's public nuisance statute for reparations; they also seek to establish a victims' compensation fund to acknowledge, "This is sacred land, but it's also a crime scene."

With a black poverty rate over double that of whites, a history of police brutality, the 2016 killing of an unarmed Terence Crutcher, and an interstate in the middle of Tulsa re-enforcing de facto segregation, it's also what many black residents argue is "a continual massacre." "Tulsa is very much a microcosm," says the director of a new documentary about the 1921 massacre. "All the issues the country is continuing to confront or struggle with are writ large." Among descendants of the massacre, they're magnified by a keen awareness of the generational wealth lost to them, a sense "of where I could be versus where I am." Those tensions came into stark relief when Monday's big Remember & Rise event, featuring headliner John Legend and keynote speaker Stacey Abrams, was abruptly canceled after a squabble over reparations. A deal to pay just $100,000 to each survivor and $2 million in seed money for a descendants' fund fell apart after their lead attorney reportedly upped the amount to $1 million each and $50 million for the fund. Many supported the change, blasting the exploitation of survivors and their stories in the name of profit. "Yes, how dare (they) ask for 10% of the $30 MILLION raised by a committee that wants to display them onstage at an event ABOUT THEIR SUFFERING," fumed one, "expecting them to be grateful while the descendants of those who burned Greenwood to the ground keep profiting/exploiting them for tourism." For survivors, meanwhile, the trauma remains. Testifying recently about reparations, Viola Fletcher, the oldest survivor, told Congress, "I am here seeking justice" for a crime she relives every day: "I still see smoke and smell fire." 100 years later, with clear memories of the mob, she still sleeps sitting up on a couch with the lights on. "Being in the dark, I can't see how to get out," she said. "I can't see who is coming in."