SUBSCRIBE TO OUR FREE NEWSLETTER

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

5

#000000

#FFFFFF

To donate by check, phone, or other method, see our More Ways to Give page.

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

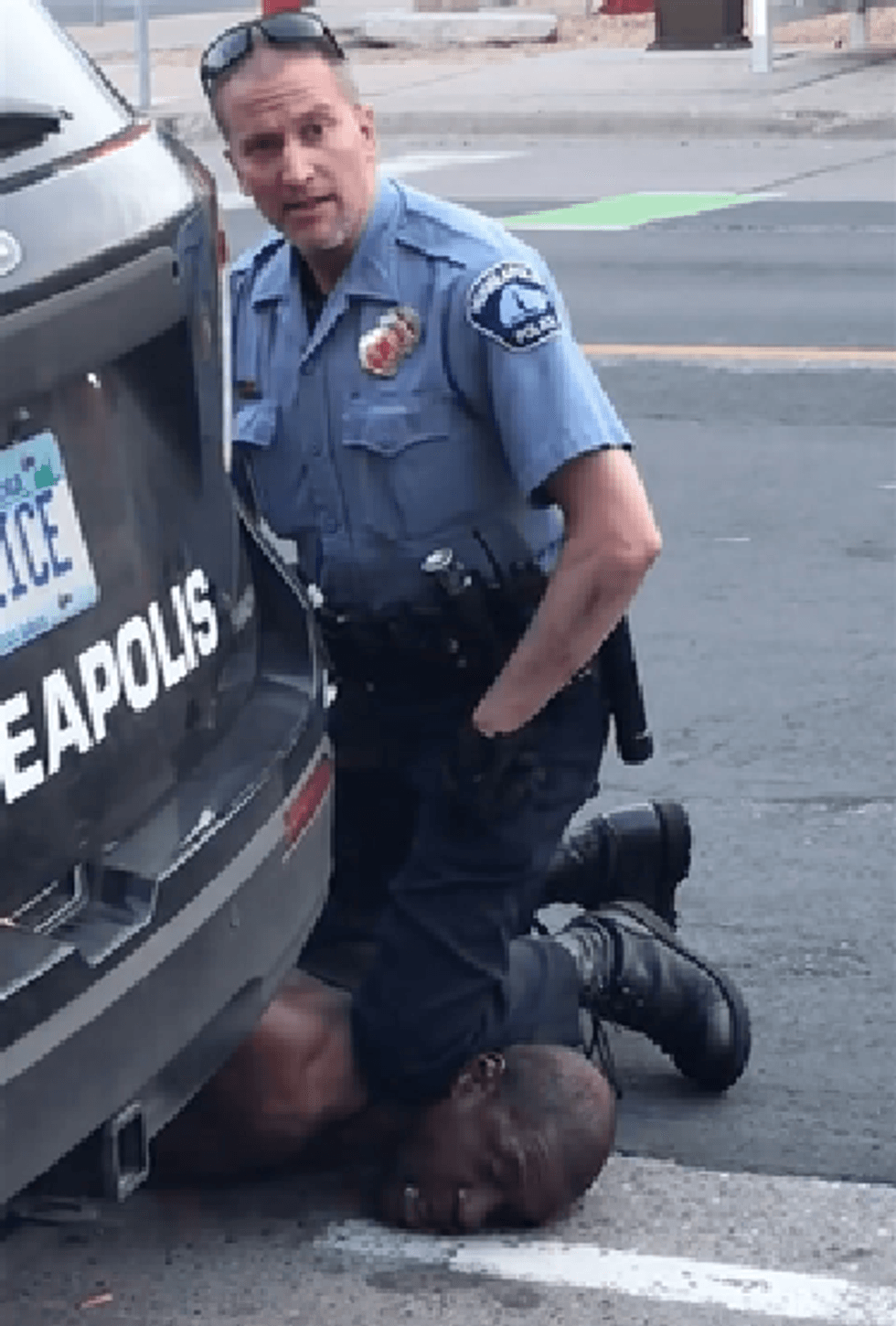

In a trial you'd think would be superfluous after the whole world saw him kneel on George Floyd's neck for almost nine minutes, the judge in Derek Chauvin's case is weighing delaying or moving the trial after the defense argued news of the city's huge setttlement with Floyd's family was "very suspicious." The judge will also consider a defense motion to allow evidence of Floyd's prior arrest, because smears work well when you're scrambling to prove it isn't a crime to kill a black man on film.

Photo by Star Tribune

On the second day of jury selection in a trial you could reasonably surmise would be superfluous given the whole world saw and heard a white cop kneel on the neck of a pleading black man for eight minutes and 46 seconds until he stopped breathing - "We watched the murder, notes one horrified observer" - the judge in the trial of Derek Chauvin is weighing whether to delay or move the trial after defense attorneys argued the timing of the city's announcement of a massive settlement with George Floyd's family was "very suspicious." Hennepin County District Judge Peter Cahill will also consider allowing evidence of a prior arrest of Floyd because for lawyers desperately flailing to prove it isn't a crime to kill a black man on film, drug smears tend to work well. In the trial in a heavily guarded tower in downtown Minneapolis, Chauvin is facing charges of second-degree murder, second-degree manslaughter and third-degree murder, which requires a lower burden of proof, in the death of Floyd. The trial of three more complicit, former Minneapolis cops is scheduled for August. No new jurors were seated Tuesday thanks to the machinations of defense attorneys, leaving the current roster at nine - two white women in their 50s, three white men in their 30s and 20s, two black men in their 30s, one Hispanic man in his 20s, one bi-racial woman in her 20s. Despite an unusually detailed questionnaire to screen potential jurors, many have been quickly dismissed: A 75-year-old man who was "appalled" by the video of Floyd's death and couldn't watch the whole thing, a teacher of kids of color who said "I couldn't go back and look at my students and my colleagues." The first chosen juror was a chemist who said he believes "all lives matter equally." The defense rejected a Hispanic mother of three - at first claiming her English wasn't good enough, and when that didn't work, without cause - who said, "We are all humans."

Much of Tuesday's proceedings focused on the city's announcement of a $27 million wrongful death settlement, its largest payout for police misconduct, to Floyd's family. Surprisingly clumsy lead defense attorney Eric Nelson said he found "concerning" a news conference where "they're using (very) well-designed terminology - 'The unanimous decision of the city council' - that has incredible propensity to taint the jury pool," though you'd think video of your sociopathic guy murdering a black man in broad daylight, with his knee on his neck and zero fucks to give about who sees it, would be more concerning. The judge agreed the timing of the settlement was "unfortunate," but said he didn't find "any evil intent" therein. He ultimately granted a defense motion to speak to the nine seated jurors on Wednesday to determine if the news threatened their ability to be impartial; he also said he'd consider their motion to delay or move the trial. Having earlier rejected it, Cahill also agreed to consider a defense motion to allow evidence of what Chauvin lawyers called "a remarkably similar" arrest of Floyd a year before his death, when he allegedly tried to ingest opiates during a traffic stop after police witnessed his "furtive behavior," cop-ese for a big black guy driving. Lawyers noted Floyd "saying some of the exact same things that he says in this case," including tearfully calling for his mother, it's unclear why they'd find that mournful information damning, not moving. Cahill said he may allow paramedics' findings of Floyd's "bodily response" to a large amount of drugs, but wouldn't allow any effort to tell jurors not to "feel sympathy for him because he was taking drugs," though he could have added someone with a drug problem doesn't usually get an extra-judicial death sentence. Prosecutors slammed the defense move as a desperate attempt "to smear Mr. Floyd's character by showing that when he is struggling with an opioid addiction, like so many Americans do, it's really just evidence of bad character."

While legal experts predict the prosecution will rely heavily on the "devastating" cellphone video recorded by Darnella Frazier, the "seminal issue" of the case will be George Floyd's cause of death, and what Chauvin did to precipitate it. Autopsy results from medical experts hired by the city and Floyd's family respectively offer conflicting stories: The city ruled his death a homicide caused by heart attack along with police restraint, neck compression, heart disease and drug use, but not asphyxiation; the family's medical examiner found asphyxiation. With no proof, Eric Nelson argues Floyd "most likely" died of drug overdose, adding he posed a safety risk to the four officers: "What Mr. Chauvin saw was a strong man struggling mightily with (police ), which seemed contradictory to Mr. Floyd's claims about not being able to breathe." His claim, in turn, seems stunningly contradictory to the searing image of Chauvin, knee on Floyd's neck, hands in nonchalant pockets. Still, if you thought this would be easy, you were wrong. To a beleaguered community where "prayers are needed" and the millions nationwide who rose up in fury against the systemic racism Floyd's murder personified, conviction seems a no-brainer: Floyd was not resisting and was begging for his life as a stone-faced Chauvin kept his knee on his neck. But legal experts say multiple murky issues - the definition of causation and Chauvin's part in it, the common-law edict Chauvin had to have a "depraved mind" to be guilty of homicide, the unpredictability of battling medical testimony, a still-racist nation of such short memories that, a year after the horrific fact, the number of those who believe in Chauvin's guilt has reportedly dropped from 60% to under 30% - make the outcome uncertain. For Floyd's family, however, "what we know is clear. George Floyd was alive before his encounter with police, and he was dead after that encounter."

Update: After Cahill's talk with jurors, he removed two who understandably said, yes, the fact the city paid Floyd's family $27 million might suggest police did something wrong. And so it begins. Nobody has suggested just how and where they can find jurors who have no opinion about one of the most savage, clear-cut and high-profile police brutality cases in the country, and that's saying something.

Photo by Star Tribune

A.P. photo

Dear Common Dreams reader, The U.S. is on a fast track to authoritarianism like nothing I've ever seen. Meanwhile, corporate news outlets are utterly capitulating to Trump, twisting their coverage to avoid drawing his ire while lining up to stuff cash in his pockets. That's why I believe that Common Dreams is doing the best and most consequential reporting that we've ever done. Our small but mighty team is a progressive reporting powerhouse, covering the news every day that the corporate media never will. Our mission has always been simple: To inform. To inspire. And to ignite change for the common good. Now here's the key piece that I want all our readers to understand: None of this would be possible without your financial support. That's not just some fundraising cliche. It's the absolute and literal truth. We don't accept corporate advertising and never will. We don't have a paywall because we don't think people should be blocked from critical news based on their ability to pay. Everything we do is funded by the donations of readers like you. Will you donate now to help power the nonprofit, independent reporting of Common Dreams? Thank you for being a vital member of our community. Together, we can keep independent journalism alive when it’s needed most. - Craig Brown, Co-founder |

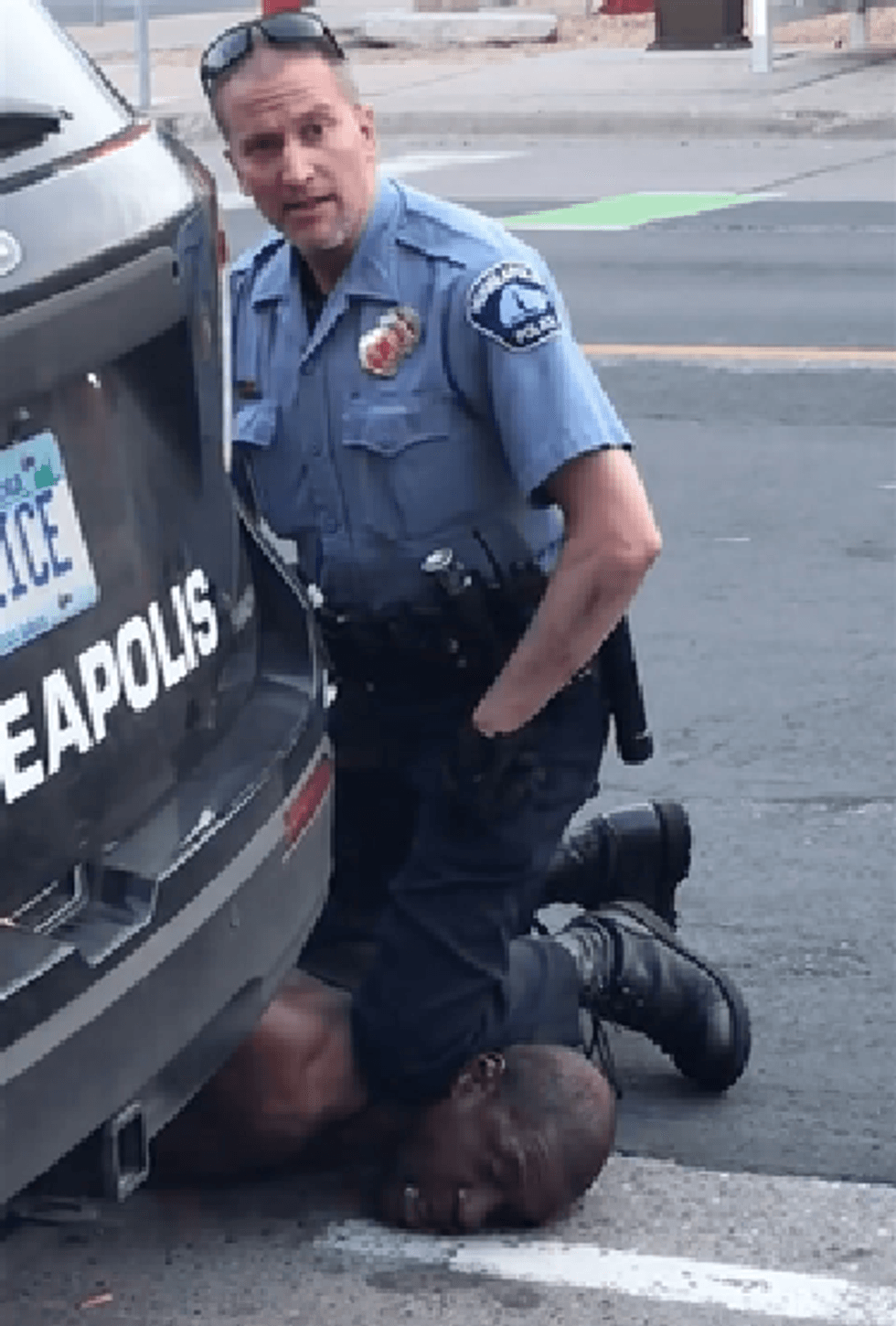

Photo by Star Tribune

On the second day of jury selection in a trial you could reasonably surmise would be superfluous given the whole world saw and heard a white cop kneel on the neck of a pleading black man for eight minutes and 46 seconds until he stopped breathing - "We watched the murder, notes one horrified observer" - the judge in the trial of Derek Chauvin is weighing whether to delay or move the trial after defense attorneys argued the timing of the city's announcement of a massive settlement with George Floyd's family was "very suspicious." Hennepin County District Judge Peter Cahill will also consider allowing evidence of a prior arrest of Floyd because for lawyers desperately flailing to prove it isn't a crime to kill a black man on film, drug smears tend to work well. In the trial in a heavily guarded tower in downtown Minneapolis, Chauvin is facing charges of second-degree murder, second-degree manslaughter and third-degree murder, which requires a lower burden of proof, in the death of Floyd. The trial of three more complicit, former Minneapolis cops is scheduled for August. No new jurors were seated Tuesday thanks to the machinations of defense attorneys, leaving the current roster at nine - two white women in their 50s, three white men in their 30s and 20s, two black men in their 30s, one Hispanic man in his 20s, one bi-racial woman in her 20s. Despite an unusually detailed questionnaire to screen potential jurors, many have been quickly dismissed: A 75-year-old man who was "appalled" by the video of Floyd's death and couldn't watch the whole thing, a teacher of kids of color who said "I couldn't go back and look at my students and my colleagues." The first chosen juror was a chemist who said he believes "all lives matter equally." The defense rejected a Hispanic mother of three - at first claiming her English wasn't good enough, and when that didn't work, without cause - who said, "We are all humans."

Much of Tuesday's proceedings focused on the city's announcement of a $27 million wrongful death settlement, its largest payout for police misconduct, to Floyd's family. Surprisingly clumsy lead defense attorney Eric Nelson said he found "concerning" a news conference where "they're using (very) well-designed terminology - 'The unanimous decision of the city council' - that has incredible propensity to taint the jury pool," though you'd think video of your sociopathic guy murdering a black man in broad daylight, with his knee on his neck and zero fucks to give about who sees it, would be more concerning. The judge agreed the timing of the settlement was "unfortunate," but said he didn't find "any evil intent" therein. He ultimately granted a defense motion to speak to the nine seated jurors on Wednesday to determine if the news threatened their ability to be impartial; he also said he'd consider their motion to delay or move the trial. Having earlier rejected it, Cahill also agreed to consider a defense motion to allow evidence of what Chauvin lawyers called "a remarkably similar" arrest of Floyd a year before his death, when he allegedly tried to ingest opiates during a traffic stop after police witnessed his "furtive behavior," cop-ese for a big black guy driving. Lawyers noted Floyd "saying some of the exact same things that he says in this case," including tearfully calling for his mother, it's unclear why they'd find that mournful information damning, not moving. Cahill said he may allow paramedics' findings of Floyd's "bodily response" to a large amount of drugs, but wouldn't allow any effort to tell jurors not to "feel sympathy for him because he was taking drugs," though he could have added someone with a drug problem doesn't usually get an extra-judicial death sentence. Prosecutors slammed the defense move as a desperate attempt "to smear Mr. Floyd's character by showing that when he is struggling with an opioid addiction, like so many Americans do, it's really just evidence of bad character."

While legal experts predict the prosecution will rely heavily on the "devastating" cellphone video recorded by Darnella Frazier, the "seminal issue" of the case will be George Floyd's cause of death, and what Chauvin did to precipitate it. Autopsy results from medical experts hired by the city and Floyd's family respectively offer conflicting stories: The city ruled his death a homicide caused by heart attack along with police restraint, neck compression, heart disease and drug use, but not asphyxiation; the family's medical examiner found asphyxiation. With no proof, Eric Nelson argues Floyd "most likely" died of drug overdose, adding he posed a safety risk to the four officers: "What Mr. Chauvin saw was a strong man struggling mightily with (police ), which seemed contradictory to Mr. Floyd's claims about not being able to breathe." His claim, in turn, seems stunningly contradictory to the searing image of Chauvin, knee on Floyd's neck, hands in nonchalant pockets. Still, if you thought this would be easy, you were wrong. To a beleaguered community where "prayers are needed" and the millions nationwide who rose up in fury against the systemic racism Floyd's murder personified, conviction seems a no-brainer: Floyd was not resisting and was begging for his life as a stone-faced Chauvin kept his knee on his neck. But legal experts say multiple murky issues - the definition of causation and Chauvin's part in it, the common-law edict Chauvin had to have a "depraved mind" to be guilty of homicide, the unpredictability of battling medical testimony, a still-racist nation of such short memories that, a year after the horrific fact, the number of those who believe in Chauvin's guilt has reportedly dropped from 60% to under 30% - make the outcome uncertain. For Floyd's family, however, "what we know is clear. George Floyd was alive before his encounter with police, and he was dead after that encounter."

Update: After Cahill's talk with jurors, he removed two who understandably said, yes, the fact the city paid Floyd's family $27 million might suggest police did something wrong. And so it begins. Nobody has suggested just how and where they can find jurors who have no opinion about one of the most savage, clear-cut and high-profile police brutality cases in the country, and that's saying something.

Photo by Star Tribune

A.P. photo

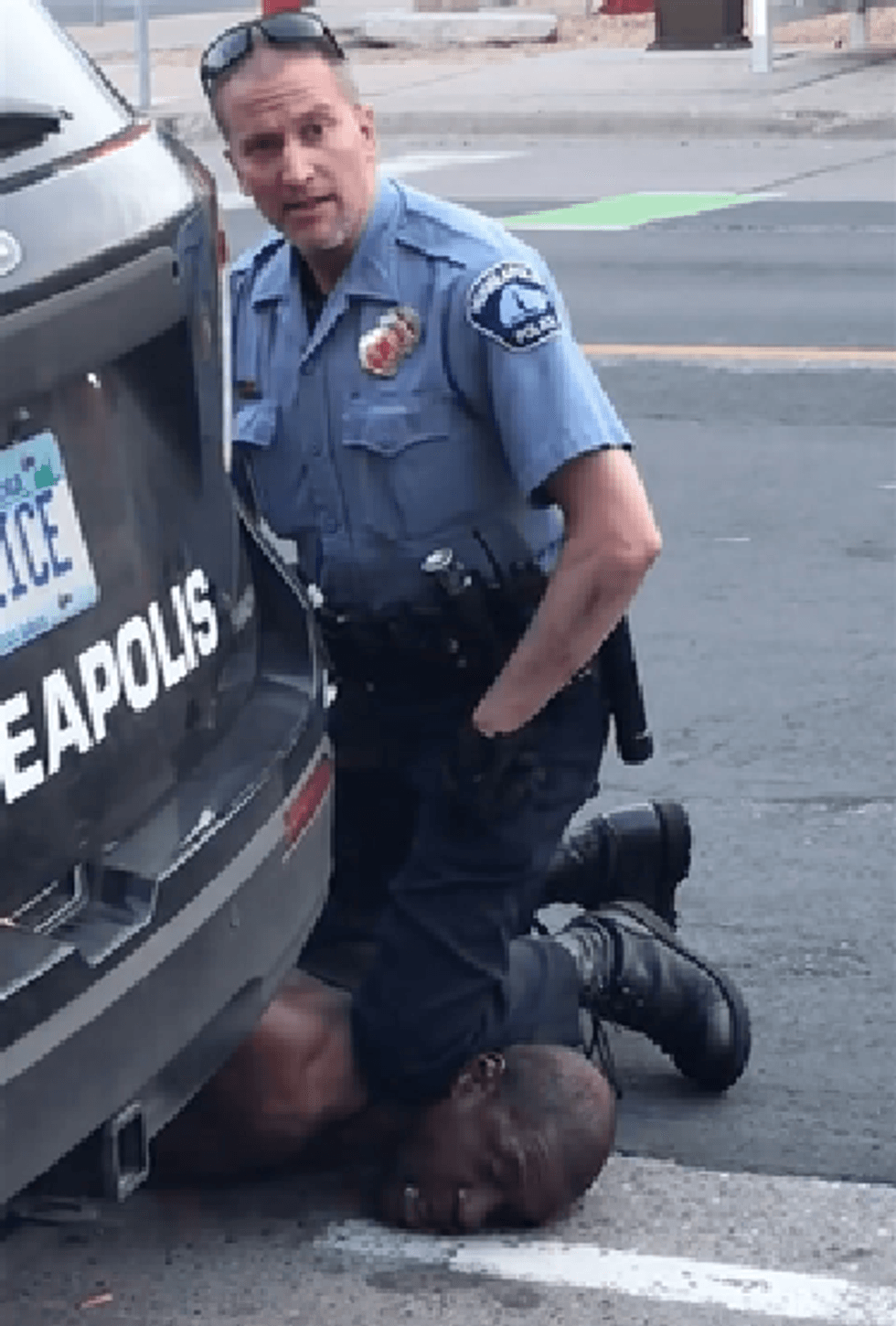

Photo by Star Tribune

On the second day of jury selection in a trial you could reasonably surmise would be superfluous given the whole world saw and heard a white cop kneel on the neck of a pleading black man for eight minutes and 46 seconds until he stopped breathing - "We watched the murder, notes one horrified observer" - the judge in the trial of Derek Chauvin is weighing whether to delay or move the trial after defense attorneys argued the timing of the city's announcement of a massive settlement with George Floyd's family was "very suspicious." Hennepin County District Judge Peter Cahill will also consider allowing evidence of a prior arrest of Floyd because for lawyers desperately flailing to prove it isn't a crime to kill a black man on film, drug smears tend to work well. In the trial in a heavily guarded tower in downtown Minneapolis, Chauvin is facing charges of second-degree murder, second-degree manslaughter and third-degree murder, which requires a lower burden of proof, in the death of Floyd. The trial of three more complicit, former Minneapolis cops is scheduled for August. No new jurors were seated Tuesday thanks to the machinations of defense attorneys, leaving the current roster at nine - two white women in their 50s, three white men in their 30s and 20s, two black men in their 30s, one Hispanic man in his 20s, one bi-racial woman in her 20s. Despite an unusually detailed questionnaire to screen potential jurors, many have been quickly dismissed: A 75-year-old man who was "appalled" by the video of Floyd's death and couldn't watch the whole thing, a teacher of kids of color who said "I couldn't go back and look at my students and my colleagues." The first chosen juror was a chemist who said he believes "all lives matter equally." The defense rejected a Hispanic mother of three - at first claiming her English wasn't good enough, and when that didn't work, without cause - who said, "We are all humans."

Much of Tuesday's proceedings focused on the city's announcement of a $27 million wrongful death settlement, its largest payout for police misconduct, to Floyd's family. Surprisingly clumsy lead defense attorney Eric Nelson said he found "concerning" a news conference where "they're using (very) well-designed terminology - 'The unanimous decision of the city council' - that has incredible propensity to taint the jury pool," though you'd think video of your sociopathic guy murdering a black man in broad daylight, with his knee on his neck and zero fucks to give about who sees it, would be more concerning. The judge agreed the timing of the settlement was "unfortunate," but said he didn't find "any evil intent" therein. He ultimately granted a defense motion to speak to the nine seated jurors on Wednesday to determine if the news threatened their ability to be impartial; he also said he'd consider their motion to delay or move the trial. Having earlier rejected it, Cahill also agreed to consider a defense motion to allow evidence of what Chauvin lawyers called "a remarkably similar" arrest of Floyd a year before his death, when he allegedly tried to ingest opiates during a traffic stop after police witnessed his "furtive behavior," cop-ese for a big black guy driving. Lawyers noted Floyd "saying some of the exact same things that he says in this case," including tearfully calling for his mother, it's unclear why they'd find that mournful information damning, not moving. Cahill said he may allow paramedics' findings of Floyd's "bodily response" to a large amount of drugs, but wouldn't allow any effort to tell jurors not to "feel sympathy for him because he was taking drugs," though he could have added someone with a drug problem doesn't usually get an extra-judicial death sentence. Prosecutors slammed the defense move as a desperate attempt "to smear Mr. Floyd's character by showing that when he is struggling with an opioid addiction, like so many Americans do, it's really just evidence of bad character."

While legal experts predict the prosecution will rely heavily on the "devastating" cellphone video recorded by Darnella Frazier, the "seminal issue" of the case will be George Floyd's cause of death, and what Chauvin did to precipitate it. Autopsy results from medical experts hired by the city and Floyd's family respectively offer conflicting stories: The city ruled his death a homicide caused by heart attack along with police restraint, neck compression, heart disease and drug use, but not asphyxiation; the family's medical examiner found asphyxiation. With no proof, Eric Nelson argues Floyd "most likely" died of drug overdose, adding he posed a safety risk to the four officers: "What Mr. Chauvin saw was a strong man struggling mightily with (police ), which seemed contradictory to Mr. Floyd's claims about not being able to breathe." His claim, in turn, seems stunningly contradictory to the searing image of Chauvin, knee on Floyd's neck, hands in nonchalant pockets. Still, if you thought this would be easy, you were wrong. To a beleaguered community where "prayers are needed" and the millions nationwide who rose up in fury against the systemic racism Floyd's murder personified, conviction seems a no-brainer: Floyd was not resisting and was begging for his life as a stone-faced Chauvin kept his knee on his neck. But legal experts say multiple murky issues - the definition of causation and Chauvin's part in it, the common-law edict Chauvin had to have a "depraved mind" to be guilty of homicide, the unpredictability of battling medical testimony, a still-racist nation of such short memories that, a year after the horrific fact, the number of those who believe in Chauvin's guilt has reportedly dropped from 60% to under 30% - make the outcome uncertain. For Floyd's family, however, "what we know is clear. George Floyd was alive before his encounter with police, and he was dead after that encounter."

Update: After Cahill's talk with jurors, he removed two who understandably said, yes, the fact the city paid Floyd's family $27 million might suggest police did something wrong. And so it begins. Nobody has suggested just how and where they can find jurors who have no opinion about one of the most savage, clear-cut and high-profile police brutality cases in the country, and that's saying something.

Photo by Star Tribune

A.P. photo