SUBSCRIBE TO OUR FREE NEWSLETTER

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

5

#000000

#FFFFFF

To donate by check, phone, or other method, see our More Ways to Give page.

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

In retrospect, the events that summer Tuesday - some planned, most spontaneous, and all more hostage to eventualities than planning - would become emblematic of the trajectory of the nation's racial and political dynamics for the next 50 years.

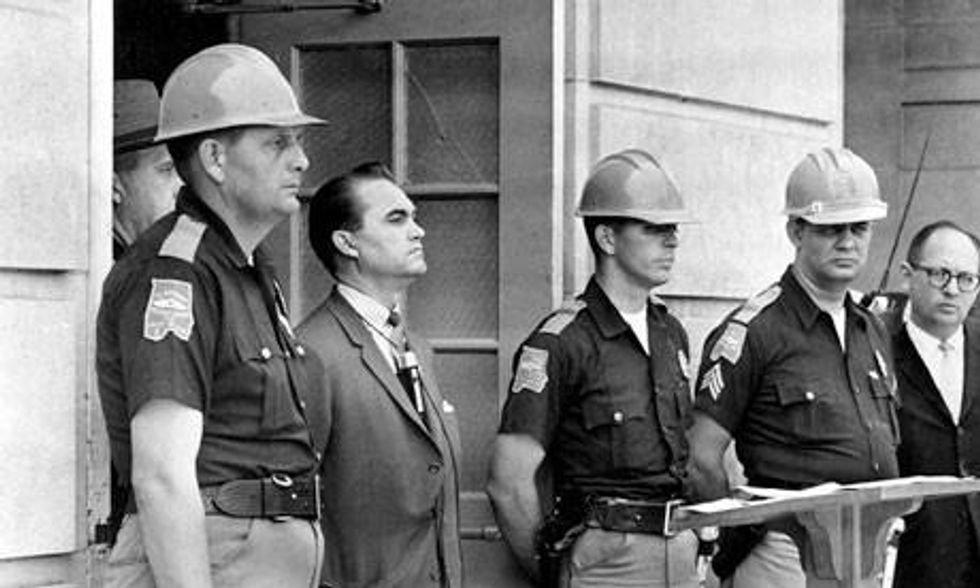

Bobby Kennedy was trying to work out the federal government's options for getting two black students, Vivian Malone and James Hood, registered for classes on campus at the university. A few hours later, in a choreographed piece of brinkmanship, Alabama's segregationist governor, George Wallace, stood at the entrance to the Foster auditorium, flanked by state troopers, to refuse them entry. The students went to their dorms while Deputy Attorney General Nicholas Katzenbach ordered Wallace to allow them in. Wallace refused and delivered a speech on states' rights.

President Kennedy then federalised the Alabama national guard and ordered Wallace's removal. "Sir, it is my sad duty to ask you to step aside under the orders of the President of the United States," said General Henry Graham. Wallace made another quick announcement, stepped aside and Malone and Hood registered.

"They knew he would step aside," Cully Clark, author of The Schoolhouse Door: Segregation's Last Stand at the University of Alabama, told NPR. "I think the fundamental question was how."

"It had been little more than a ceremony of futility," wrote journalist and Wallace biographer Marshall Frady:

"And, as a historical moment, a rather pedestrian production. But no other southern governor had managed to strike even that dramatic a pose of defiance and it has never been required of southern popular heroes that they be successful. Indeed, southerners tend to love their heroes more for their losses."

The previous day the president's inner circle was divided as to whether he should deliver a televised national address on civil rights. They decided to wait and see how things went in Alabama. After the incident had passed with more theatre than chaos, they unanimously advised the speech was now unnecessary.

Kennedy decided to ignore them, calling executives at the three television networks himself to request airtime. In The Bystander, Nick Bryant describes how, with only six hours to write the speech, Kennedy's team struggled to pull anything coherent together. Minutes before the cameras rolled, all they had was a bundle of typed pages interspersed with illegible scribbles. His secretary had no time to type up a final version and his speechwriters had not come up with a conclusion. With the cameras on, Kennedy started reading from the text and, for the last four minutes, improvised with lines he'd used before from the campaign trail and elsewhere.

"If an American, because his skin is dark, cannot eat lunch in a restaurant open to the public, if he cannot send his children to the best public school available, if he cannot vote for the public officials who will represent him, if, in short, he cannot enjoy the full and free life which all of us want, then who among us would be content to have the color of his skin changed and stand in his place? Who among us would then be content with the counsels of patience and delay?"

Kennedy went on to reflect on the issues of black unemployment and the slow pace of integration, described how the south was embarrassing the nation in front of its cold war adversaries and announced plans to introduce civil rights legislation. In Bryant's assessment:

"The speech was the most courageous of Kennedy's presidency. After two years of equivocation on the subject of civil rights, Kennedy had finally sought to mobilize that vast body of Americans who had long considered segregation immoral, and who were certainly unprepared to countenance the most extreme forms of discrimination."

A thousand miles away, in Jackson, Mississippi, Myrlie Evers - who, in 2013, would deliver the invocation at President Barack Obama's second inauguration - had watched the presidential address in bed with her three children. Her husband, Medgar, the field secretary of the state's National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (the NAACP, the oldest civil rights organisation in the country), arrived home just after midnight from a meeting with activists in a local church, carrying white T-shirts announcing "Jim Crow Must Go".

Lurking in the honeysuckle bushes across the road with a 30.06 bolt-action Winchester hunting rifle was Byron DeLa Beckwith, a fertilizer salesman and Klan member from nearby Greenwood. The sound of Evers slamming the car door was followed rapidly by a burst of gunfire. Myrlie ran downstairs while the children assumed the position they had learned to adopt if their house ever came under attack. By the time she reached the front door, Medgar's body was slumped in front of her. A bullet had gone through his back and exited through his chest. A few hours later, he was pronounced dead.

On the day of Medgar Evers' funeral, around 1,000 black youths marched through town, joined later by their elders. When police ordered them to disperse, scuffles broke out. The crowd chanted:

"We want the killer."

Meeting their demand should not have been difficult. The rifle that was fired was traced to Beckwith, whose fingerprints were on its telescopic sight. Some witnesses reported seeing a man who fit his description in the area that night, as well as a car that looked like his white Plymouth Valiant. If that wasn't enough, he'd openly bragged to fellow Klansmen about carrying out the shooting. Though it took several weeks, he was eventually arrested on the strength of this overwhelming evidence, and charged with the murder.

It was then that matters took an all-too predictable turn. Not once, but twice, in the course of 1964, all-white juries twice failed to reach a verdict. Beckwith was arrested again in 1990, and finally found guilty in 1994. He wore a confederate flag pin throughout the hearings. He died in prison in 2001.

Between them, these three events, which all took place within a day, would signal the end of a period of gruesome certainty in America's racial politics - and the beginning of an era of greater complexity. What soon became evident was threefold: the economic stratification within black America, the political realignment of southern politics and the evolution of the struggle of equality from the streets to the legislature.

Wallace's otiose performance and Beckwith's murderous assault typified the segregationists' endgame: a series of dramatic, often violent, acts perpetrated by the local state or its ideological surrogates, with no strategic value beyond symbolizing resistance and inciting a response. They were not intended to stop integration, but to protest its inevitability. And while those protests were futile, they nonetheless retained the ability to provoke, as the disturbances following Evers' funeral testified.

The years to come were sufficiently volatile that even ostensibly minor events, such as a traffic stop in Watts, Los Angeles, or the raid of a late-night drinking den in Detroit, could spark major unrest. The violence and chaos that ensued polarised communities - not on issues of ideology or strategy, but on the basis of race, in a manner that weakened the already dim prospects for solidarity across the colour line.

As Myrlie Evers, who went on to dedicate her life to nonviolent interracial activism, recalled:

"When Medgar was felled by that shot, and I rushed out and saw him lying there and people from the neighbourhood began to gather, there were also some whose colour happened to be white. I don't think I have ever hated as much in my life as I did at that particular moment anyone who had white skin."

In Malone and Hood's registration at the University of Alabama that day, we saw the doors to higher education and, through them, career advancement, reluctantly being opened for the small section of black America that was in a position, at that time, to reap the fruits of integration. There had been a middle class in black America for a long time, but as long as segregation existed, the material benefits deriving from that status were significantly circumscribed, particularly in the south.

Race dominated almost everything. A black doctor or dentist could not live outside particular neighbourhoods, nor eat in certain establishments, nor be served in certain stores. Whatever class differences existed within the black community, and there were many, they were inevitably subsumed under the broader struggle for equality.

With integration, however, came the fracturing of black communities, as those equipped to take advantage of the new opportunities forged ahead, leaving the rest to struggle with the legacy of the past 300 years. Wealthier people could move to the suburbs, their kids could integrate in white schools, and from there go on to top universities.

But this success brought its own challenges. The doors of opportunity were only opened to a few - but enough for some to ask, in the absence of legal barriers, that if some could make it, then why not others. Black Americans no longer fell foul of the law of the land, yet still remained on the wrong side of the law of probabilities: more likely to be arrested, convicted and imprisoned; less likely to be employed, promoted and educated.

For most black Americans, the end of segregation did not feel like the liberation that had been promised. After the Watts riots, Martin Luther King told Bayard Rustin, who organised the March on Washington:

"You know Bayard, I worked to get these people the right to eat hamburgers, and now I've got to do something ... to help them get the money to buy them."

With Kennedy's appeal for legislation, we saw the shift in focus moving from the streets of Birmingham to Washington's corridors of power. This was progress. Changing the law had been the point of the protests. Within a year, Lyndon B Johnson, who that November assumed the presidency in the wake of Kennedy's assassination, signed the Civil Rights Act; within two years, he'd signed the Voting Rights Act.

But the shift from protesters' demands to congressional bills limited possibilities for radical transformation. Clear moral demands were replaced by horsetrading. Marchers cannot be stopped by a filibuster; legislation can. Rustin's argument ran as follows:

"We were moving from a period of protest to one of political responsibility. That is, instead of marching on the courthouse, or the restaurant or the theatre, we now had to march the ballot box. In protest, there must never be any compromise. In politics, there is always compromise."

The trouble was the nature of the deal-making was itself in flux. By aligning himself with civil rights, Kennedy would end the Democratic party's dominance of the south. The next day, southern Democrats would respond by defeating a routine funding bill. "[Civil rights] is overwhelming the whole, the whole program," House majority leader Carl Albert told him. "I couldn't do a damn thing with them."

Veteran journalist Bill Moyers wrote that when Johnson passed the Civil Rights Act a year later, "he was euphoric'":

"But late that very night, I found him in a melancholy mood as he lay in bed reading the bulldog edition of the Washington Post with headlines celebrating the day. I asked him what was troubling him. 'I think we just delivered the south to the Republican party for a long time to come,' he said."

Johnson's fears were well-founded. The Republicans, sensing an opportunity, decided to pitch a clear appeal to southern segregationists in particular, and suburban whites in general, on the grounds of race. This would create a thoroughgoing transformation in the nation's politics that is only today, in the 21st century, beginning to unravel.

"We're not generating enough angry white guys to stay in business for the long term," Republican Senator Lindsey Graham said shortly before the last presidential election.

That day, 11 June 1963, epitomised the beginning of the end for business as usual.

Donald Trump’s attacks on democracy, justice, and a free press are escalating — putting everything we stand for at risk. We believe a better world is possible, but we can’t get there without your support. Common Dreams stands apart. We answer only to you — our readers, activists, and changemakers — not to billionaires or corporations. Our independence allows us to cover the vital stories that others won’t, spotlighting movements for peace, equality, and human rights. Right now, our work faces unprecedented challenges. Misinformation is spreading, journalists are under attack, and financial pressures are mounting. As a reader-supported, nonprofit newsroom, your support is crucial to keep this journalism alive. Whatever you can give — $10, $25, or $100 — helps us stay strong and responsive when the world needs us most. Together, we’ll continue to build the independent, courageous journalism our movement relies on. Thank you for being part of this community. |

In retrospect, the events that summer Tuesday - some planned, most spontaneous, and all more hostage to eventualities than planning - would become emblematic of the trajectory of the nation's racial and political dynamics for the next 50 years.

Bobby Kennedy was trying to work out the federal government's options for getting two black students, Vivian Malone and James Hood, registered for classes on campus at the university. A few hours later, in a choreographed piece of brinkmanship, Alabama's segregationist governor, George Wallace, stood at the entrance to the Foster auditorium, flanked by state troopers, to refuse them entry. The students went to their dorms while Deputy Attorney General Nicholas Katzenbach ordered Wallace to allow them in. Wallace refused and delivered a speech on states' rights.

President Kennedy then federalised the Alabama national guard and ordered Wallace's removal. "Sir, it is my sad duty to ask you to step aside under the orders of the President of the United States," said General Henry Graham. Wallace made another quick announcement, stepped aside and Malone and Hood registered.

"They knew he would step aside," Cully Clark, author of The Schoolhouse Door: Segregation's Last Stand at the University of Alabama, told NPR. "I think the fundamental question was how."

"It had been little more than a ceremony of futility," wrote journalist and Wallace biographer Marshall Frady:

"And, as a historical moment, a rather pedestrian production. But no other southern governor had managed to strike even that dramatic a pose of defiance and it has never been required of southern popular heroes that they be successful. Indeed, southerners tend to love their heroes more for their losses."

The previous day the president's inner circle was divided as to whether he should deliver a televised national address on civil rights. They decided to wait and see how things went in Alabama. After the incident had passed with more theatre than chaos, they unanimously advised the speech was now unnecessary.

Kennedy decided to ignore them, calling executives at the three television networks himself to request airtime. In The Bystander, Nick Bryant describes how, with only six hours to write the speech, Kennedy's team struggled to pull anything coherent together. Minutes before the cameras rolled, all they had was a bundle of typed pages interspersed with illegible scribbles. His secretary had no time to type up a final version and his speechwriters had not come up with a conclusion. With the cameras on, Kennedy started reading from the text and, for the last four minutes, improvised with lines he'd used before from the campaign trail and elsewhere.

"If an American, because his skin is dark, cannot eat lunch in a restaurant open to the public, if he cannot send his children to the best public school available, if he cannot vote for the public officials who will represent him, if, in short, he cannot enjoy the full and free life which all of us want, then who among us would be content to have the color of his skin changed and stand in his place? Who among us would then be content with the counsels of patience and delay?"

Kennedy went on to reflect on the issues of black unemployment and the slow pace of integration, described how the south was embarrassing the nation in front of its cold war adversaries and announced plans to introduce civil rights legislation. In Bryant's assessment:

"The speech was the most courageous of Kennedy's presidency. After two years of equivocation on the subject of civil rights, Kennedy had finally sought to mobilize that vast body of Americans who had long considered segregation immoral, and who were certainly unprepared to countenance the most extreme forms of discrimination."

A thousand miles away, in Jackson, Mississippi, Myrlie Evers - who, in 2013, would deliver the invocation at President Barack Obama's second inauguration - had watched the presidential address in bed with her three children. Her husband, Medgar, the field secretary of the state's National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (the NAACP, the oldest civil rights organisation in the country), arrived home just after midnight from a meeting with activists in a local church, carrying white T-shirts announcing "Jim Crow Must Go".

Lurking in the honeysuckle bushes across the road with a 30.06 bolt-action Winchester hunting rifle was Byron DeLa Beckwith, a fertilizer salesman and Klan member from nearby Greenwood. The sound of Evers slamming the car door was followed rapidly by a burst of gunfire. Myrlie ran downstairs while the children assumed the position they had learned to adopt if their house ever came under attack. By the time she reached the front door, Medgar's body was slumped in front of her. A bullet had gone through his back and exited through his chest. A few hours later, he was pronounced dead.

On the day of Medgar Evers' funeral, around 1,000 black youths marched through town, joined later by their elders. When police ordered them to disperse, scuffles broke out. The crowd chanted:

"We want the killer."

Meeting their demand should not have been difficult. The rifle that was fired was traced to Beckwith, whose fingerprints were on its telescopic sight. Some witnesses reported seeing a man who fit his description in the area that night, as well as a car that looked like his white Plymouth Valiant. If that wasn't enough, he'd openly bragged to fellow Klansmen about carrying out the shooting. Though it took several weeks, he was eventually arrested on the strength of this overwhelming evidence, and charged with the murder.

It was then that matters took an all-too predictable turn. Not once, but twice, in the course of 1964, all-white juries twice failed to reach a verdict. Beckwith was arrested again in 1990, and finally found guilty in 1994. He wore a confederate flag pin throughout the hearings. He died in prison in 2001.

Between them, these three events, which all took place within a day, would signal the end of a period of gruesome certainty in America's racial politics - and the beginning of an era of greater complexity. What soon became evident was threefold: the economic stratification within black America, the political realignment of southern politics and the evolution of the struggle of equality from the streets to the legislature.

Wallace's otiose performance and Beckwith's murderous assault typified the segregationists' endgame: a series of dramatic, often violent, acts perpetrated by the local state or its ideological surrogates, with no strategic value beyond symbolizing resistance and inciting a response. They were not intended to stop integration, but to protest its inevitability. And while those protests were futile, they nonetheless retained the ability to provoke, as the disturbances following Evers' funeral testified.

The years to come were sufficiently volatile that even ostensibly minor events, such as a traffic stop in Watts, Los Angeles, or the raid of a late-night drinking den in Detroit, could spark major unrest. The violence and chaos that ensued polarised communities - not on issues of ideology or strategy, but on the basis of race, in a manner that weakened the already dim prospects for solidarity across the colour line.

As Myrlie Evers, who went on to dedicate her life to nonviolent interracial activism, recalled:

"When Medgar was felled by that shot, and I rushed out and saw him lying there and people from the neighbourhood began to gather, there were also some whose colour happened to be white. I don't think I have ever hated as much in my life as I did at that particular moment anyone who had white skin."

In Malone and Hood's registration at the University of Alabama that day, we saw the doors to higher education and, through them, career advancement, reluctantly being opened for the small section of black America that was in a position, at that time, to reap the fruits of integration. There had been a middle class in black America for a long time, but as long as segregation existed, the material benefits deriving from that status were significantly circumscribed, particularly in the south.

Race dominated almost everything. A black doctor or dentist could not live outside particular neighbourhoods, nor eat in certain establishments, nor be served in certain stores. Whatever class differences existed within the black community, and there were many, they were inevitably subsumed under the broader struggle for equality.

With integration, however, came the fracturing of black communities, as those equipped to take advantage of the new opportunities forged ahead, leaving the rest to struggle with the legacy of the past 300 years. Wealthier people could move to the suburbs, their kids could integrate in white schools, and from there go on to top universities.

But this success brought its own challenges. The doors of opportunity were only opened to a few - but enough for some to ask, in the absence of legal barriers, that if some could make it, then why not others. Black Americans no longer fell foul of the law of the land, yet still remained on the wrong side of the law of probabilities: more likely to be arrested, convicted and imprisoned; less likely to be employed, promoted and educated.

For most black Americans, the end of segregation did not feel like the liberation that had been promised. After the Watts riots, Martin Luther King told Bayard Rustin, who organised the March on Washington:

"You know Bayard, I worked to get these people the right to eat hamburgers, and now I've got to do something ... to help them get the money to buy them."

With Kennedy's appeal for legislation, we saw the shift in focus moving from the streets of Birmingham to Washington's corridors of power. This was progress. Changing the law had been the point of the protests. Within a year, Lyndon B Johnson, who that November assumed the presidency in the wake of Kennedy's assassination, signed the Civil Rights Act; within two years, he'd signed the Voting Rights Act.

But the shift from protesters' demands to congressional bills limited possibilities for radical transformation. Clear moral demands were replaced by horsetrading. Marchers cannot be stopped by a filibuster; legislation can. Rustin's argument ran as follows:

"We were moving from a period of protest to one of political responsibility. That is, instead of marching on the courthouse, or the restaurant or the theatre, we now had to march the ballot box. In protest, there must never be any compromise. In politics, there is always compromise."

The trouble was the nature of the deal-making was itself in flux. By aligning himself with civil rights, Kennedy would end the Democratic party's dominance of the south. The next day, southern Democrats would respond by defeating a routine funding bill. "[Civil rights] is overwhelming the whole, the whole program," House majority leader Carl Albert told him. "I couldn't do a damn thing with them."

Veteran journalist Bill Moyers wrote that when Johnson passed the Civil Rights Act a year later, "he was euphoric'":

"But late that very night, I found him in a melancholy mood as he lay in bed reading the bulldog edition of the Washington Post with headlines celebrating the day. I asked him what was troubling him. 'I think we just delivered the south to the Republican party for a long time to come,' he said."

Johnson's fears were well-founded. The Republicans, sensing an opportunity, decided to pitch a clear appeal to southern segregationists in particular, and suburban whites in general, on the grounds of race. This would create a thoroughgoing transformation in the nation's politics that is only today, in the 21st century, beginning to unravel.

"We're not generating enough angry white guys to stay in business for the long term," Republican Senator Lindsey Graham said shortly before the last presidential election.

That day, 11 June 1963, epitomised the beginning of the end for business as usual.

In retrospect, the events that summer Tuesday - some planned, most spontaneous, and all more hostage to eventualities than planning - would become emblematic of the trajectory of the nation's racial and political dynamics for the next 50 years.

Bobby Kennedy was trying to work out the federal government's options for getting two black students, Vivian Malone and James Hood, registered for classes on campus at the university. A few hours later, in a choreographed piece of brinkmanship, Alabama's segregationist governor, George Wallace, stood at the entrance to the Foster auditorium, flanked by state troopers, to refuse them entry. The students went to their dorms while Deputy Attorney General Nicholas Katzenbach ordered Wallace to allow them in. Wallace refused and delivered a speech on states' rights.

President Kennedy then federalised the Alabama national guard and ordered Wallace's removal. "Sir, it is my sad duty to ask you to step aside under the orders of the President of the United States," said General Henry Graham. Wallace made another quick announcement, stepped aside and Malone and Hood registered.

"They knew he would step aside," Cully Clark, author of The Schoolhouse Door: Segregation's Last Stand at the University of Alabama, told NPR. "I think the fundamental question was how."

"It had been little more than a ceremony of futility," wrote journalist and Wallace biographer Marshall Frady:

"And, as a historical moment, a rather pedestrian production. But no other southern governor had managed to strike even that dramatic a pose of defiance and it has never been required of southern popular heroes that they be successful. Indeed, southerners tend to love their heroes more for their losses."

The previous day the president's inner circle was divided as to whether he should deliver a televised national address on civil rights. They decided to wait and see how things went in Alabama. After the incident had passed with more theatre than chaos, they unanimously advised the speech was now unnecessary.

Kennedy decided to ignore them, calling executives at the three television networks himself to request airtime. In The Bystander, Nick Bryant describes how, with only six hours to write the speech, Kennedy's team struggled to pull anything coherent together. Minutes before the cameras rolled, all they had was a bundle of typed pages interspersed with illegible scribbles. His secretary had no time to type up a final version and his speechwriters had not come up with a conclusion. With the cameras on, Kennedy started reading from the text and, for the last four minutes, improvised with lines he'd used before from the campaign trail and elsewhere.

"If an American, because his skin is dark, cannot eat lunch in a restaurant open to the public, if he cannot send his children to the best public school available, if he cannot vote for the public officials who will represent him, if, in short, he cannot enjoy the full and free life which all of us want, then who among us would be content to have the color of his skin changed and stand in his place? Who among us would then be content with the counsels of patience and delay?"

Kennedy went on to reflect on the issues of black unemployment and the slow pace of integration, described how the south was embarrassing the nation in front of its cold war adversaries and announced plans to introduce civil rights legislation. In Bryant's assessment:

"The speech was the most courageous of Kennedy's presidency. After two years of equivocation on the subject of civil rights, Kennedy had finally sought to mobilize that vast body of Americans who had long considered segregation immoral, and who were certainly unprepared to countenance the most extreme forms of discrimination."

A thousand miles away, in Jackson, Mississippi, Myrlie Evers - who, in 2013, would deliver the invocation at President Barack Obama's second inauguration - had watched the presidential address in bed with her three children. Her husband, Medgar, the field secretary of the state's National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (the NAACP, the oldest civil rights organisation in the country), arrived home just after midnight from a meeting with activists in a local church, carrying white T-shirts announcing "Jim Crow Must Go".

Lurking in the honeysuckle bushes across the road with a 30.06 bolt-action Winchester hunting rifle was Byron DeLa Beckwith, a fertilizer salesman and Klan member from nearby Greenwood. The sound of Evers slamming the car door was followed rapidly by a burst of gunfire. Myrlie ran downstairs while the children assumed the position they had learned to adopt if their house ever came under attack. By the time she reached the front door, Medgar's body was slumped in front of her. A bullet had gone through his back and exited through his chest. A few hours later, he was pronounced dead.

On the day of Medgar Evers' funeral, around 1,000 black youths marched through town, joined later by their elders. When police ordered them to disperse, scuffles broke out. The crowd chanted:

"We want the killer."

Meeting their demand should not have been difficult. The rifle that was fired was traced to Beckwith, whose fingerprints were on its telescopic sight. Some witnesses reported seeing a man who fit his description in the area that night, as well as a car that looked like his white Plymouth Valiant. If that wasn't enough, he'd openly bragged to fellow Klansmen about carrying out the shooting. Though it took several weeks, he was eventually arrested on the strength of this overwhelming evidence, and charged with the murder.

It was then that matters took an all-too predictable turn. Not once, but twice, in the course of 1964, all-white juries twice failed to reach a verdict. Beckwith was arrested again in 1990, and finally found guilty in 1994. He wore a confederate flag pin throughout the hearings. He died in prison in 2001.

Between them, these three events, which all took place within a day, would signal the end of a period of gruesome certainty in America's racial politics - and the beginning of an era of greater complexity. What soon became evident was threefold: the economic stratification within black America, the political realignment of southern politics and the evolution of the struggle of equality from the streets to the legislature.

Wallace's otiose performance and Beckwith's murderous assault typified the segregationists' endgame: a series of dramatic, often violent, acts perpetrated by the local state or its ideological surrogates, with no strategic value beyond symbolizing resistance and inciting a response. They were not intended to stop integration, but to protest its inevitability. And while those protests were futile, they nonetheless retained the ability to provoke, as the disturbances following Evers' funeral testified.

The years to come were sufficiently volatile that even ostensibly minor events, such as a traffic stop in Watts, Los Angeles, or the raid of a late-night drinking den in Detroit, could spark major unrest. The violence and chaos that ensued polarised communities - not on issues of ideology or strategy, but on the basis of race, in a manner that weakened the already dim prospects for solidarity across the colour line.

As Myrlie Evers, who went on to dedicate her life to nonviolent interracial activism, recalled:

"When Medgar was felled by that shot, and I rushed out and saw him lying there and people from the neighbourhood began to gather, there were also some whose colour happened to be white. I don't think I have ever hated as much in my life as I did at that particular moment anyone who had white skin."

In Malone and Hood's registration at the University of Alabama that day, we saw the doors to higher education and, through them, career advancement, reluctantly being opened for the small section of black America that was in a position, at that time, to reap the fruits of integration. There had been a middle class in black America for a long time, but as long as segregation existed, the material benefits deriving from that status were significantly circumscribed, particularly in the south.

Race dominated almost everything. A black doctor or dentist could not live outside particular neighbourhoods, nor eat in certain establishments, nor be served in certain stores. Whatever class differences existed within the black community, and there were many, they were inevitably subsumed under the broader struggle for equality.

With integration, however, came the fracturing of black communities, as those equipped to take advantage of the new opportunities forged ahead, leaving the rest to struggle with the legacy of the past 300 years. Wealthier people could move to the suburbs, their kids could integrate in white schools, and from there go on to top universities.

But this success brought its own challenges. The doors of opportunity were only opened to a few - but enough for some to ask, in the absence of legal barriers, that if some could make it, then why not others. Black Americans no longer fell foul of the law of the land, yet still remained on the wrong side of the law of probabilities: more likely to be arrested, convicted and imprisoned; less likely to be employed, promoted and educated.

For most black Americans, the end of segregation did not feel like the liberation that had been promised. After the Watts riots, Martin Luther King told Bayard Rustin, who organised the March on Washington:

"You know Bayard, I worked to get these people the right to eat hamburgers, and now I've got to do something ... to help them get the money to buy them."

With Kennedy's appeal for legislation, we saw the shift in focus moving from the streets of Birmingham to Washington's corridors of power. This was progress. Changing the law had been the point of the protests. Within a year, Lyndon B Johnson, who that November assumed the presidency in the wake of Kennedy's assassination, signed the Civil Rights Act; within two years, he'd signed the Voting Rights Act.

But the shift from protesters' demands to congressional bills limited possibilities for radical transformation. Clear moral demands were replaced by horsetrading. Marchers cannot be stopped by a filibuster; legislation can. Rustin's argument ran as follows:

"We were moving from a period of protest to one of political responsibility. That is, instead of marching on the courthouse, or the restaurant or the theatre, we now had to march the ballot box. In protest, there must never be any compromise. In politics, there is always compromise."

The trouble was the nature of the deal-making was itself in flux. By aligning himself with civil rights, Kennedy would end the Democratic party's dominance of the south. The next day, southern Democrats would respond by defeating a routine funding bill. "[Civil rights] is overwhelming the whole, the whole program," House majority leader Carl Albert told him. "I couldn't do a damn thing with them."

Veteran journalist Bill Moyers wrote that when Johnson passed the Civil Rights Act a year later, "he was euphoric'":

"But late that very night, I found him in a melancholy mood as he lay in bed reading the bulldog edition of the Washington Post with headlines celebrating the day. I asked him what was troubling him. 'I think we just delivered the south to the Republican party for a long time to come,' he said."

Johnson's fears were well-founded. The Republicans, sensing an opportunity, decided to pitch a clear appeal to southern segregationists in particular, and suburban whites in general, on the grounds of race. This would create a thoroughgoing transformation in the nation's politics that is only today, in the 21st century, beginning to unravel.

"We're not generating enough angry white guys to stay in business for the long term," Republican Senator Lindsey Graham said shortly before the last presidential election.

That day, 11 June 1963, epitomised the beginning of the end for business as usual.