SUBSCRIBE TO OUR FREE NEWSLETTER

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

5

#000000

#FFFFFF

To donate by check, phone, or other method, see our More Ways to Give page.

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

Happy fortieth, Roe! They say 40 is the new 20. And that might be fitting, because four decades later to the day it feels like in many ways we've moved back in time. While access to abortion is still in theory a right every woman in this country enjoys, an economic chasm has yawned between the well-off and the poor.

Happy fortieth, Roe! They say 40 is the new 20. And that might be fitting, because four decades later to the day it feels like in many ways we've moved back in time. While access to abortion is still in theory a right every woman in this country enjoys, an economic chasm has yawned between the well-off and the poor.

The Guttmacher Institute has some enlightening, if disheartening, infographics to celebrate the anniversary. As the first demonstrates, low-income women are the majority of those who seek abortions:

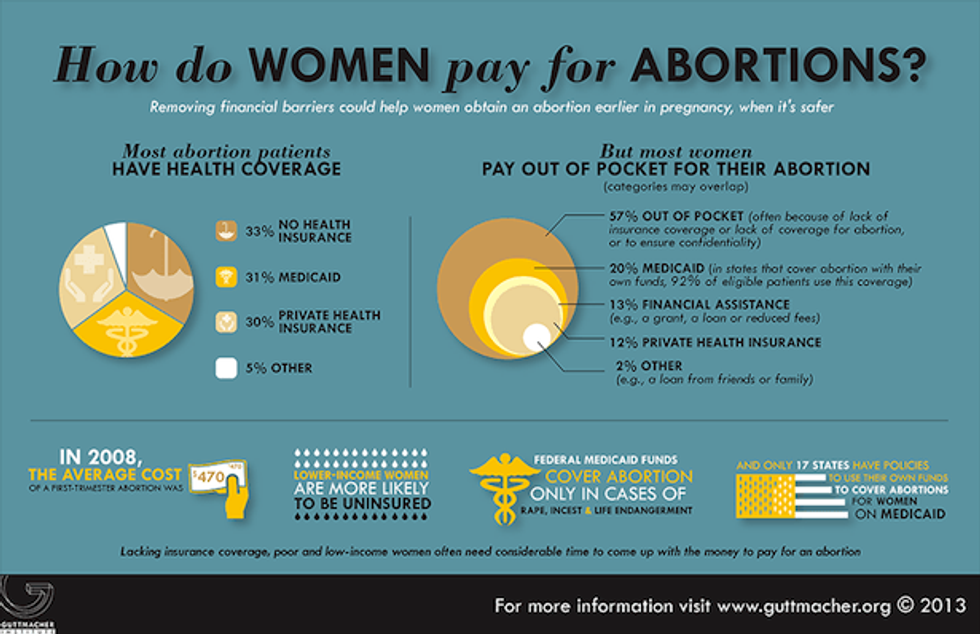

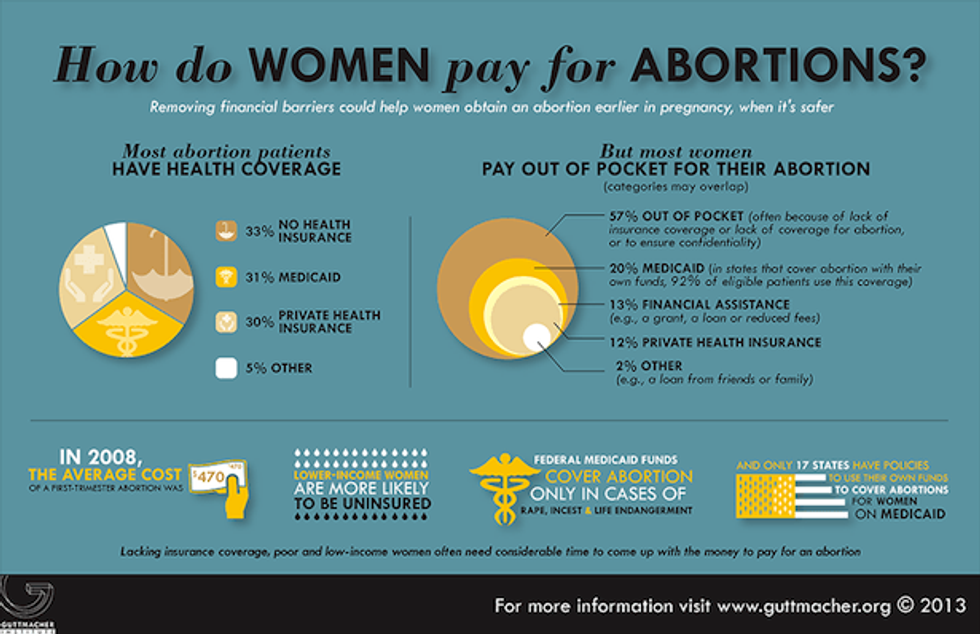

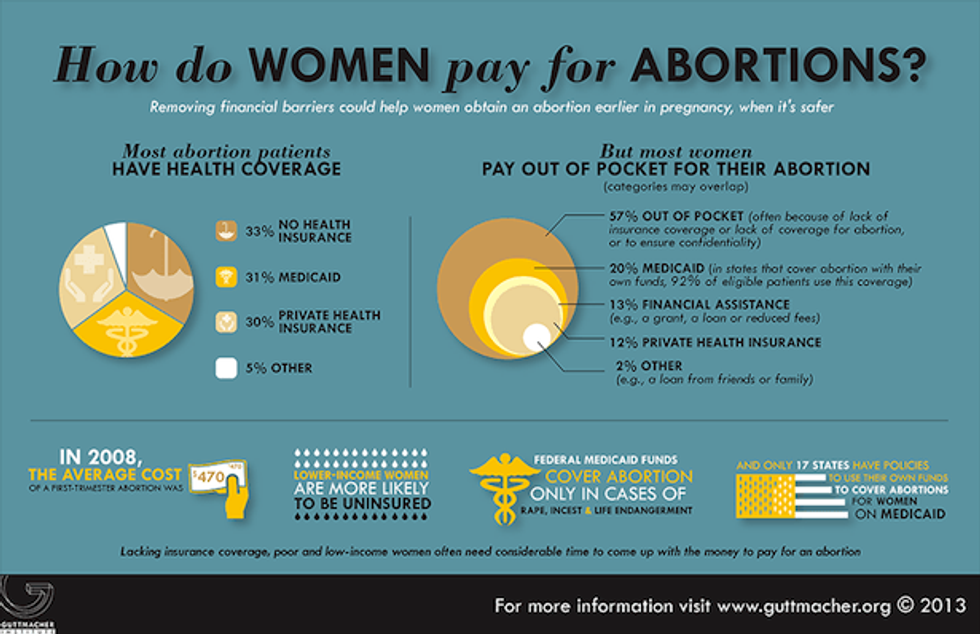

Their abortion rates are five times those of wealthier women. Yet it may be hardest for them to get the services they need. The average cost of a first-term abortion is $470, and many women are paying for that out of pocket:

A third of all abortion patients don't have any health insurance to help defray the cost. Even so, most women don't use insurance anyway - almost 60 percent pay out of pocket. Only about 20 percent use Medicaid, since those funds are prohibited from financing an abortion unless it results from rape, incest or endangers the life of the mother. Some states go even further in restricting its use, while only seventeen use their own funds to patch that hole for low-income women on Medicaid in need of an abortion.

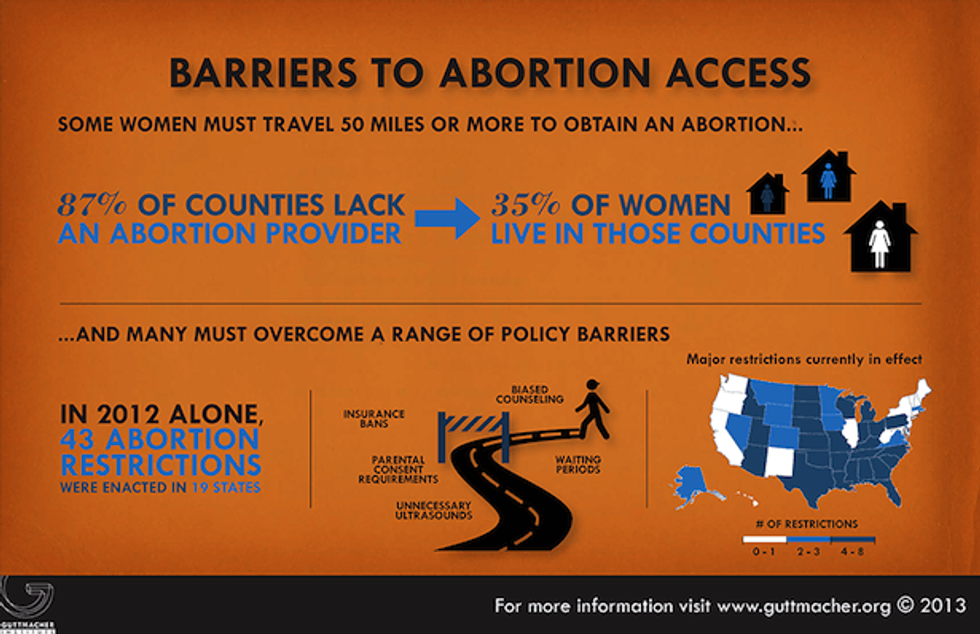

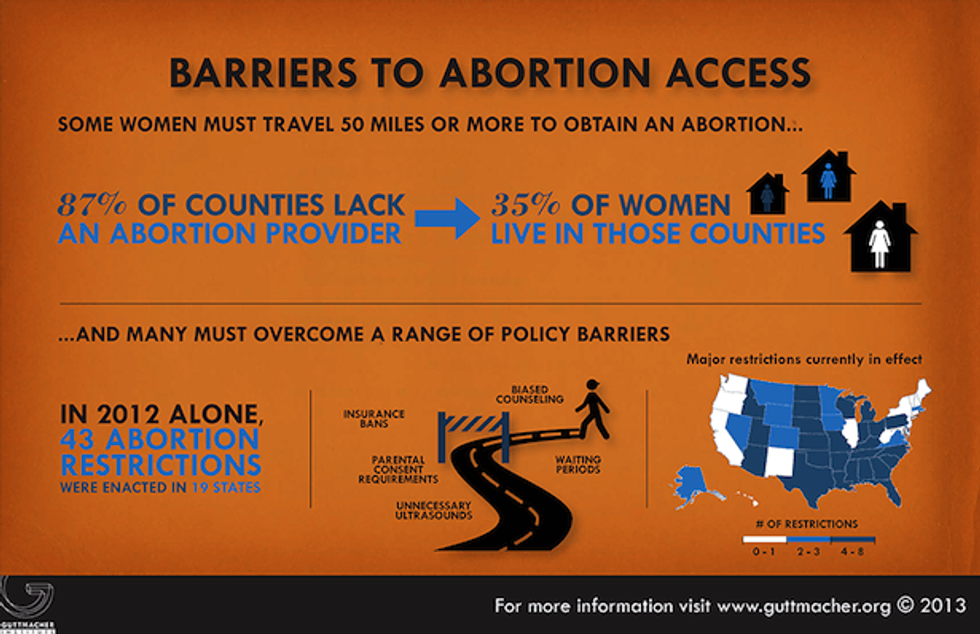

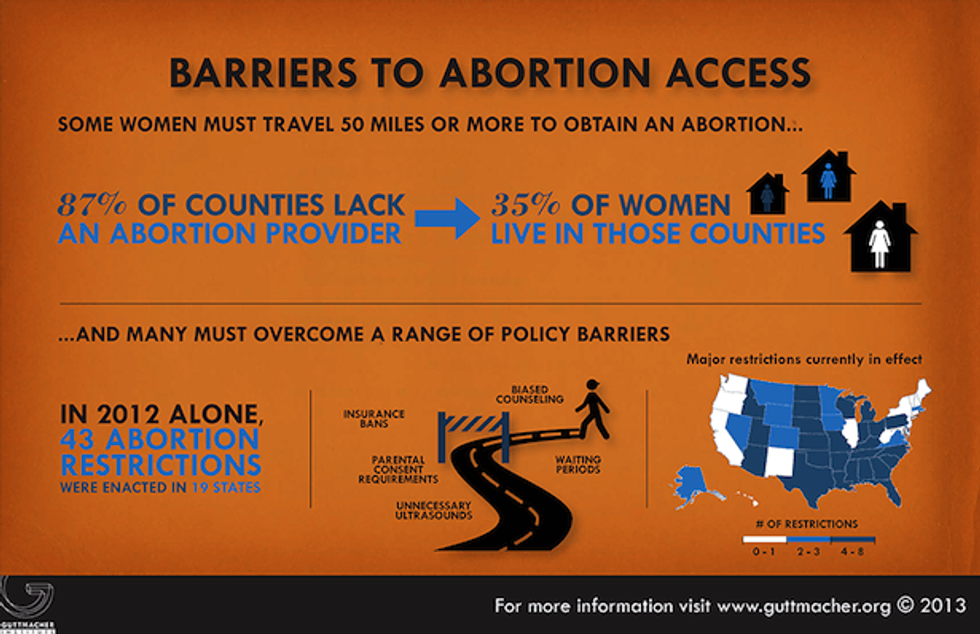

But payment is only one piece of the puzzle. As the Nation editors recently noted, "87 percent of US counties lack an abortion provider, and several states have only a clinic or two staffed by a doctor who flies in from another state." Thirty-five percent of all the country's women live in those counties that don't have a provider:

That means that some women have to travel more than fifty miles to obtain an abortion. Doing so requires time off work, transportation, lodging and child care, all of which start to bloat the cost very quickly. Once they get to the provider, they may face even more restrictions, such as waiting periods that mean they have to stick around for an extra twenty-four hours between the initial counseling session and the actual procedure, spending more money and losing more wages. They may have to pay for a medically unnecessary ultrasound. Suddenly a safe medical procedure that is the legal right of every woman becomes a near impossibility for those who don't have enough money to foot all the bills.

As Guttmacher reports, "Women report having to borrow money from friends & family and forgo paying rent, groceries, & utilities to pay for their procedure." Some may just not be able to scrape it all together. That could be part of why low-income women have an unplanned birth rate six times that of more well to do women.

The anniversary of the landmark case that paved the way for legal abortion isn't just marked by doom and gloom. As the Nation editors point out, twenty new pro-choice legislators were elected to Congress in the last election. Last year was another record year for the number of abortion restrictions enacted at the state level, but it was down a bit from the year before.

But it's clear that this is no time to drop our guard. The election also gave Republicans supermajority control over the legislatures of fifteen states, and four states already have plans to keep whittling away reproductive rights. If they have their way, abortion access will almost certainly continue to disappear, particularly for women who have fewer resources. Forty years later, some women can access abortion--but it's far from a need-blind right.

Dear Common Dreams reader, The U.S. is on a fast track to authoritarianism like nothing I've ever seen. Meanwhile, corporate news outlets are utterly capitulating to Trump, twisting their coverage to avoid drawing his ire while lining up to stuff cash in his pockets. That's why I believe that Common Dreams is doing the best and most consequential reporting that we've ever done. Our small but mighty team is a progressive reporting powerhouse, covering the news every day that the corporate media never will. Our mission has always been simple: To inform. To inspire. And to ignite change for the common good. Now here's the key piece that I want all our readers to understand: None of this would be possible without your financial support. That's not just some fundraising cliche. It's the absolute and literal truth. We don't accept corporate advertising and never will. We don't have a paywall because we don't think people should be blocked from critical news based on their ability to pay. Everything we do is funded by the donations of readers like you. Will you donate now to help power the nonprofit, independent reporting of Common Dreams? Thank you for being a vital member of our community. Together, we can keep independent journalism alive when it’s needed most. - Craig Brown, Co-founder |

Happy fortieth, Roe! They say 40 is the new 20. And that might be fitting, because four decades later to the day it feels like in many ways we've moved back in time. While access to abortion is still in theory a right every woman in this country enjoys, an economic chasm has yawned between the well-off and the poor.

The Guttmacher Institute has some enlightening, if disheartening, infographics to celebrate the anniversary. As the first demonstrates, low-income women are the majority of those who seek abortions:

Their abortion rates are five times those of wealthier women. Yet it may be hardest for them to get the services they need. The average cost of a first-term abortion is $470, and many women are paying for that out of pocket:

A third of all abortion patients don't have any health insurance to help defray the cost. Even so, most women don't use insurance anyway - almost 60 percent pay out of pocket. Only about 20 percent use Medicaid, since those funds are prohibited from financing an abortion unless it results from rape, incest or endangers the life of the mother. Some states go even further in restricting its use, while only seventeen use their own funds to patch that hole for low-income women on Medicaid in need of an abortion.

But payment is only one piece of the puzzle. As the Nation editors recently noted, "87 percent of US counties lack an abortion provider, and several states have only a clinic or two staffed by a doctor who flies in from another state." Thirty-five percent of all the country's women live in those counties that don't have a provider:

That means that some women have to travel more than fifty miles to obtain an abortion. Doing so requires time off work, transportation, lodging and child care, all of which start to bloat the cost very quickly. Once they get to the provider, they may face even more restrictions, such as waiting periods that mean they have to stick around for an extra twenty-four hours between the initial counseling session and the actual procedure, spending more money and losing more wages. They may have to pay for a medically unnecessary ultrasound. Suddenly a safe medical procedure that is the legal right of every woman becomes a near impossibility for those who don't have enough money to foot all the bills.

As Guttmacher reports, "Women report having to borrow money from friends & family and forgo paying rent, groceries, & utilities to pay for their procedure." Some may just not be able to scrape it all together. That could be part of why low-income women have an unplanned birth rate six times that of more well to do women.

The anniversary of the landmark case that paved the way for legal abortion isn't just marked by doom and gloom. As the Nation editors point out, twenty new pro-choice legislators were elected to Congress in the last election. Last year was another record year for the number of abortion restrictions enacted at the state level, but it was down a bit from the year before.

But it's clear that this is no time to drop our guard. The election also gave Republicans supermajority control over the legislatures of fifteen states, and four states already have plans to keep whittling away reproductive rights. If they have their way, abortion access will almost certainly continue to disappear, particularly for women who have fewer resources. Forty years later, some women can access abortion--but it's far from a need-blind right.

Happy fortieth, Roe! They say 40 is the new 20. And that might be fitting, because four decades later to the day it feels like in many ways we've moved back in time. While access to abortion is still in theory a right every woman in this country enjoys, an economic chasm has yawned between the well-off and the poor.

The Guttmacher Institute has some enlightening, if disheartening, infographics to celebrate the anniversary. As the first demonstrates, low-income women are the majority of those who seek abortions:

Their abortion rates are five times those of wealthier women. Yet it may be hardest for them to get the services they need. The average cost of a first-term abortion is $470, and many women are paying for that out of pocket:

A third of all abortion patients don't have any health insurance to help defray the cost. Even so, most women don't use insurance anyway - almost 60 percent pay out of pocket. Only about 20 percent use Medicaid, since those funds are prohibited from financing an abortion unless it results from rape, incest or endangers the life of the mother. Some states go even further in restricting its use, while only seventeen use their own funds to patch that hole for low-income women on Medicaid in need of an abortion.

But payment is only one piece of the puzzle. As the Nation editors recently noted, "87 percent of US counties lack an abortion provider, and several states have only a clinic or two staffed by a doctor who flies in from another state." Thirty-five percent of all the country's women live in those counties that don't have a provider:

That means that some women have to travel more than fifty miles to obtain an abortion. Doing so requires time off work, transportation, lodging and child care, all of which start to bloat the cost very quickly. Once they get to the provider, they may face even more restrictions, such as waiting periods that mean they have to stick around for an extra twenty-four hours between the initial counseling session and the actual procedure, spending more money and losing more wages. They may have to pay for a medically unnecessary ultrasound. Suddenly a safe medical procedure that is the legal right of every woman becomes a near impossibility for those who don't have enough money to foot all the bills.

As Guttmacher reports, "Women report having to borrow money from friends & family and forgo paying rent, groceries, & utilities to pay for their procedure." Some may just not be able to scrape it all together. That could be part of why low-income women have an unplanned birth rate six times that of more well to do women.

The anniversary of the landmark case that paved the way for legal abortion isn't just marked by doom and gloom. As the Nation editors point out, twenty new pro-choice legislators were elected to Congress in the last election. Last year was another record year for the number of abortion restrictions enacted at the state level, but it was down a bit from the year before.

But it's clear that this is no time to drop our guard. The election also gave Republicans supermajority control over the legislatures of fifteen states, and four states already have plans to keep whittling away reproductive rights. If they have their way, abortion access will almost certainly continue to disappear, particularly for women who have fewer resources. Forty years later, some women can access abortion--but it's far from a need-blind right.