SUBSCRIBE TO OUR FREE NEWSLETTER

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

5

#000000

#FFFFFF

To donate by check, phone, or other method, see our More Ways to Give page.

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

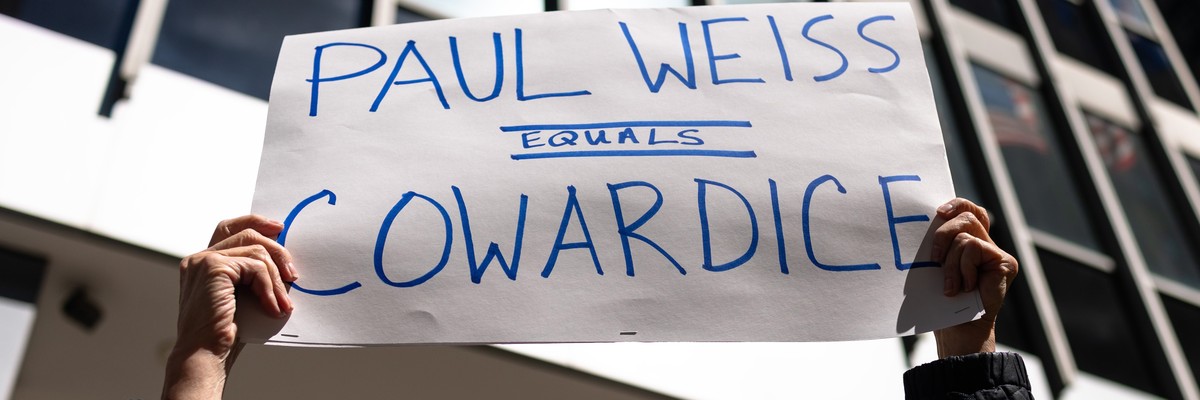

People hold signs as they protest outside of the offices of Paul, Weiss, Rifkind, Wharton, & Garrison LLP on March 25, 2025 in New York City.

As Trump’s courtroom defeats pile up, the Big Law firms that settled face new uncertainties about their attorneys, their clients, and their futures.

President Donald Trump and the Big Law firms that surrendered to his unconstitutional executive orders suffered another bad week.

In a 52-page opinion, U.S. District Court Judge John D. Bates—a 2001 appointee of President George W. Bush—rejected the Justice Department’s effort to defend Trump’s executive order targeting Jenner & Block. Trump’s own words doomed it:

Like the others in the series, this order—which takes aim at the global law firm Jenner & Block—makes no bones about why it chose its target: It picked Jenner because of the causes Jenner champions, the clients Jenner represents, and a lawyer Jenner once employed. (Jenner & Block v. U.S. Department of Justice, et al. Civil Action No. 25-916 (JDB) p. 1)

The court left no doubt that Trump had violated the Constitution:

Going after law firms in this way is doubly violative of the Constitution. Most obviously, retaliating against firms for the views embodied in their legal work—and thereby seeking to muzzle them going forward—violates the First Amendment’s central command that government may not “use the power of the State to punish or suppress disfavored expression.” (Id.; citations omitted.)

Describing how Trump’s actions undermine democracy, Judge Bates previewed the fate awaiting similar orders:

This order, like the others, seeks to chill legal representation the administration doesn’t like, thereby insulating the Executive Branch from the judicial check fundamental to the separation of powers. It thus violates the Constitution and the Court will enjoin its operation in full. (Id.; emphasis supplied.)

The firms that challenged Trump remain undefeated in the courtroom.

Judge Bates sent a message to firms that settled: They should not have “bowed” to Trump. (Id. at p. 1). Calling out the first firm to settle—Paul, Weiss, Wharton, Rifkin, & Garrison—the court seemed incredulous that “[o]ther firms skipped straight to negotiations. Without ever receiving an executive order, these firms preemptively bargained with the administration and struck deals sparing them.” But the firms that settled merely created worse problems for themselves:

“A firm fearing or laboring under an order like this one feels pressure to avoid arguments and clients the administration disdains in the hope of escaping government-imposed disabilities. Meanwhile, a firm that has acceded to the administration’s demands by cutting a deal feels the same pressure to retain “the President’s ongoing approval.“ Either way, the order pits firms’ “loyal[ty] to client interests“ against a competing interest in pleasing the President. (Id. at p. 16; citations omitted.)

Urging that “‘[t]he right to sue and defend in the courts’” is “‘the right conservative of all other rights, and lies at the foundation of orderly government,’” Judge Bates continued:

Our society has entrusted lawyers with something of a monopoly on the exercise of this foundational right—on translating real-world harm into courtroom argument. Sometimes they live up to that trust; sometimes they don’t. (Id. at p. 17; emphasis supplied.)

The firms that settled blew it.

As they take a well-deserved public beating, the settling firms also produced new and enduring sources of internal instability. In early May, Paul Weiss partner and former Homeland Security Secretary Jeh Johnson announced his retirement to become co-chair of Columbia University’s Board of Trustees. Johnson’s departure followed the exit of Steven Banks, the firm’s pro bono practice leader.

On the same day that Judge Bates issued his opinion, litigation department co-chair Karen Dunn and three prominent Paul Weiss partners—Bill Isaacson, Jeanine Rhee, and Jessica Phillips—left to form a new firm. Dunn had assisted former presidential nominee Kamala Harris with debate preparation. Isaacson is one of the country’s leading antitrust lawyers. Rhee was former deputy assistant attorney general at the Office of Legal Counsel under President Barack Obama. Phillips was a former clerk for U.S. Supreme Court Justice Samuel Alito. Their new firm will operate free of Paul Weiss’ restrictive settlement terms.

Among those restrictive terms are mandatory pro bono legal services to Trump-approved causes. Paul Weiss, Skadden Arps, Kirkland, & Ellis and other settling firms are fielding such requests and generating unwanted publicity.

Conservative Newsmax host Greta Van Susteren pressed Skadden to represent a veteran wanting to sue a Michigan judge who had issued a protective order against him in a divorce. When the firm equivocated, Van Susteren blasted Skadden on X, where she has more than one million followers. The New York Times covered the episode on the front page of its May 26, 2025 print edition.

It could get worse. Trump’s April 28 executive order requires Attorney General Pam Bondi to use Big Law pro bono legal services in defending law enforcement officials accused of civil rights violations and other misconduct.

Let’s summarize the damage so far:

First, Trump’s courtroom defeats will continue; appellate judges will affirm those rulings; and the U.S. Supreme Court won’t bail him out this time. But he won the things he wanted most: neutralizing powerful potential courtroom adversaries, a $1 billion war chest, and a stunning public relations victory over powerful institutions that could have slowed his drive toward autocracy—all thanks to the firms that capitulated.

Second, government attorneys trying to save Trump’s unconstitutional orders are suffering irreparable career damage to their reputations. They’re losing credibility defending the indefensible with specious arguments and abandoning their sworn obligations to uphold the Constitution and the rule of law.

Finally, the Big Law firms that settled face new uncertainties about their attorneys, their clients, and their futures. They could admit their monumental mistakes, cut their losses, and walk away from a bad deal that is becoming worse by the day. But that would require humility, sound judgment, and a spine.

|

Trump and Musk are on an unconstitutional rampage, aiming for virtually every corner of the federal government. These two right-wing billionaires are targeting nurses, scientists, teachers, daycare providers, judges, veterans, air traffic controllers, and nuclear safety inspectors. No one is safe. The food stamps program, Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid are next. It’s an unprecedented disaster and a five-alarm fire, but there will be a reckoning. The people did not vote for this. The American people do not want this dystopian hellscape that hides behind claims of “efficiency.” Still, in reality, it is all a giveaway to corporate interests and the libertarian dreams of far-right oligarchs like Musk. Common Dreams is playing a vital role by reporting day and night on this orgy of corruption and greed, as well as what everyday people can do to organize and fight back. As a people-powered nonprofit news outlet, we cover issues the corporate media never will, but we can only continue with our readers’ support. |

President Donald Trump and the Big Law firms that surrendered to his unconstitutional executive orders suffered another bad week.

In a 52-page opinion, U.S. District Court Judge John D. Bates—a 2001 appointee of President George W. Bush—rejected the Justice Department’s effort to defend Trump’s executive order targeting Jenner & Block. Trump’s own words doomed it:

Like the others in the series, this order—which takes aim at the global law firm Jenner & Block—makes no bones about why it chose its target: It picked Jenner because of the causes Jenner champions, the clients Jenner represents, and a lawyer Jenner once employed. (Jenner & Block v. U.S. Department of Justice, et al. Civil Action No. 25-916 (JDB) p. 1)

The court left no doubt that Trump had violated the Constitution:

Going after law firms in this way is doubly violative of the Constitution. Most obviously, retaliating against firms for the views embodied in their legal work—and thereby seeking to muzzle them going forward—violates the First Amendment’s central command that government may not “use the power of the State to punish or suppress disfavored expression.” (Id.; citations omitted.)

Describing how Trump’s actions undermine democracy, Judge Bates previewed the fate awaiting similar orders:

This order, like the others, seeks to chill legal representation the administration doesn’t like, thereby insulating the Executive Branch from the judicial check fundamental to the separation of powers. It thus violates the Constitution and the Court will enjoin its operation in full. (Id.; emphasis supplied.)

The firms that challenged Trump remain undefeated in the courtroom.

Judge Bates sent a message to firms that settled: They should not have “bowed” to Trump. (Id. at p. 1). Calling out the first firm to settle—Paul, Weiss, Wharton, Rifkin, & Garrison—the court seemed incredulous that “[o]ther firms skipped straight to negotiations. Without ever receiving an executive order, these firms preemptively bargained with the administration and struck deals sparing them.” But the firms that settled merely created worse problems for themselves:

“A firm fearing or laboring under an order like this one feels pressure to avoid arguments and clients the administration disdains in the hope of escaping government-imposed disabilities. Meanwhile, a firm that has acceded to the administration’s demands by cutting a deal feels the same pressure to retain “the President’s ongoing approval.“ Either way, the order pits firms’ “loyal[ty] to client interests“ against a competing interest in pleasing the President. (Id. at p. 16; citations omitted.)

Urging that “‘[t]he right to sue and defend in the courts’” is “‘the right conservative of all other rights, and lies at the foundation of orderly government,’” Judge Bates continued:

Our society has entrusted lawyers with something of a monopoly on the exercise of this foundational right—on translating real-world harm into courtroom argument. Sometimes they live up to that trust; sometimes they don’t. (Id. at p. 17; emphasis supplied.)

The firms that settled blew it.

As they take a well-deserved public beating, the settling firms also produced new and enduring sources of internal instability. In early May, Paul Weiss partner and former Homeland Security Secretary Jeh Johnson announced his retirement to become co-chair of Columbia University’s Board of Trustees. Johnson’s departure followed the exit of Steven Banks, the firm’s pro bono practice leader.

On the same day that Judge Bates issued his opinion, litigation department co-chair Karen Dunn and three prominent Paul Weiss partners—Bill Isaacson, Jeanine Rhee, and Jessica Phillips—left to form a new firm. Dunn had assisted former presidential nominee Kamala Harris with debate preparation. Isaacson is one of the country’s leading antitrust lawyers. Rhee was former deputy assistant attorney general at the Office of Legal Counsel under President Barack Obama. Phillips was a former clerk for U.S. Supreme Court Justice Samuel Alito. Their new firm will operate free of Paul Weiss’ restrictive settlement terms.

Among those restrictive terms are mandatory pro bono legal services to Trump-approved causes. Paul Weiss, Skadden Arps, Kirkland, & Ellis and other settling firms are fielding such requests and generating unwanted publicity.

Conservative Newsmax host Greta Van Susteren pressed Skadden to represent a veteran wanting to sue a Michigan judge who had issued a protective order against him in a divorce. When the firm equivocated, Van Susteren blasted Skadden on X, where she has more than one million followers. The New York Times covered the episode on the front page of its May 26, 2025 print edition.

It could get worse. Trump’s April 28 executive order requires Attorney General Pam Bondi to use Big Law pro bono legal services in defending law enforcement officials accused of civil rights violations and other misconduct.

Let’s summarize the damage so far:

First, Trump’s courtroom defeats will continue; appellate judges will affirm those rulings; and the U.S. Supreme Court won’t bail him out this time. But he won the things he wanted most: neutralizing powerful potential courtroom adversaries, a $1 billion war chest, and a stunning public relations victory over powerful institutions that could have slowed his drive toward autocracy—all thanks to the firms that capitulated.

Second, government attorneys trying to save Trump’s unconstitutional orders are suffering irreparable career damage to their reputations. They’re losing credibility defending the indefensible with specious arguments and abandoning their sworn obligations to uphold the Constitution and the rule of law.

Finally, the Big Law firms that settled face new uncertainties about their attorneys, their clients, and their futures. They could admit their monumental mistakes, cut their losses, and walk away from a bad deal that is becoming worse by the day. But that would require humility, sound judgment, and a spine.

President Donald Trump and the Big Law firms that surrendered to his unconstitutional executive orders suffered another bad week.

In a 52-page opinion, U.S. District Court Judge John D. Bates—a 2001 appointee of President George W. Bush—rejected the Justice Department’s effort to defend Trump’s executive order targeting Jenner & Block. Trump’s own words doomed it:

Like the others in the series, this order—which takes aim at the global law firm Jenner & Block—makes no bones about why it chose its target: It picked Jenner because of the causes Jenner champions, the clients Jenner represents, and a lawyer Jenner once employed. (Jenner & Block v. U.S. Department of Justice, et al. Civil Action No. 25-916 (JDB) p. 1)

The court left no doubt that Trump had violated the Constitution:

Going after law firms in this way is doubly violative of the Constitution. Most obviously, retaliating against firms for the views embodied in their legal work—and thereby seeking to muzzle them going forward—violates the First Amendment’s central command that government may not “use the power of the State to punish or suppress disfavored expression.” (Id.; citations omitted.)

Describing how Trump’s actions undermine democracy, Judge Bates previewed the fate awaiting similar orders:

This order, like the others, seeks to chill legal representation the administration doesn’t like, thereby insulating the Executive Branch from the judicial check fundamental to the separation of powers. It thus violates the Constitution and the Court will enjoin its operation in full. (Id.; emphasis supplied.)

The firms that challenged Trump remain undefeated in the courtroom.

Judge Bates sent a message to firms that settled: They should not have “bowed” to Trump. (Id. at p. 1). Calling out the first firm to settle—Paul, Weiss, Wharton, Rifkin, & Garrison—the court seemed incredulous that “[o]ther firms skipped straight to negotiations. Without ever receiving an executive order, these firms preemptively bargained with the administration and struck deals sparing them.” But the firms that settled merely created worse problems for themselves:

“A firm fearing or laboring under an order like this one feels pressure to avoid arguments and clients the administration disdains in the hope of escaping government-imposed disabilities. Meanwhile, a firm that has acceded to the administration’s demands by cutting a deal feels the same pressure to retain “the President’s ongoing approval.“ Either way, the order pits firms’ “loyal[ty] to client interests“ against a competing interest in pleasing the President. (Id. at p. 16; citations omitted.)

Urging that “‘[t]he right to sue and defend in the courts’” is “‘the right conservative of all other rights, and lies at the foundation of orderly government,’” Judge Bates continued:

Our society has entrusted lawyers with something of a monopoly on the exercise of this foundational right—on translating real-world harm into courtroom argument. Sometimes they live up to that trust; sometimes they don’t. (Id. at p. 17; emphasis supplied.)

The firms that settled blew it.

As they take a well-deserved public beating, the settling firms also produced new and enduring sources of internal instability. In early May, Paul Weiss partner and former Homeland Security Secretary Jeh Johnson announced his retirement to become co-chair of Columbia University’s Board of Trustees. Johnson’s departure followed the exit of Steven Banks, the firm’s pro bono practice leader.

On the same day that Judge Bates issued his opinion, litigation department co-chair Karen Dunn and three prominent Paul Weiss partners—Bill Isaacson, Jeanine Rhee, and Jessica Phillips—left to form a new firm. Dunn had assisted former presidential nominee Kamala Harris with debate preparation. Isaacson is one of the country’s leading antitrust lawyers. Rhee was former deputy assistant attorney general at the Office of Legal Counsel under President Barack Obama. Phillips was a former clerk for U.S. Supreme Court Justice Samuel Alito. Their new firm will operate free of Paul Weiss’ restrictive settlement terms.

Among those restrictive terms are mandatory pro bono legal services to Trump-approved causes. Paul Weiss, Skadden Arps, Kirkland, & Ellis and other settling firms are fielding such requests and generating unwanted publicity.

Conservative Newsmax host Greta Van Susteren pressed Skadden to represent a veteran wanting to sue a Michigan judge who had issued a protective order against him in a divorce. When the firm equivocated, Van Susteren blasted Skadden on X, where she has more than one million followers. The New York Times covered the episode on the front page of its May 26, 2025 print edition.

It could get worse. Trump’s April 28 executive order requires Attorney General Pam Bondi to use Big Law pro bono legal services in defending law enforcement officials accused of civil rights violations and other misconduct.

Let’s summarize the damage so far:

First, Trump’s courtroom defeats will continue; appellate judges will affirm those rulings; and the U.S. Supreme Court won’t bail him out this time. But he won the things he wanted most: neutralizing powerful potential courtroom adversaries, a $1 billion war chest, and a stunning public relations victory over powerful institutions that could have slowed his drive toward autocracy—all thanks to the firms that capitulated.

Second, government attorneys trying to save Trump’s unconstitutional orders are suffering irreparable career damage to their reputations. They’re losing credibility defending the indefensible with specious arguments and abandoning their sworn obligations to uphold the Constitution and the rule of law.

Finally, the Big Law firms that settled face new uncertainties about their attorneys, their clients, and their futures. They could admit their monumental mistakes, cut their losses, and walk away from a bad deal that is becoming worse by the day. But that would require humility, sound judgment, and a spine.